by Heather Plett | Sep 20, 2016 | grief, growth, holding space, Intuition, journey, Uncategorized

My baby died before I got to hold him in my arms. I’d been in the hospital for three weeks, trying to save my third pregnancy, but then one morning I went downstairs for my twice-daily ultrasound and found out he had died while I slept. Then came the horrible and unavoidable realization… I had to give birth to him. For three hours I laboured, knowing that at the end of it, instead of a baby suckling at my breast, I would hold death in my arms. That’s the hardest kind of liminal space I’ve ever been through – excruciating pain on top of excruciating grief.

Yes, it was hard, but it was also one of the most tender, beautiful, grace-filled experiences of my life. It changed me profoundly, and set me on the path I am on now. That was the beginning of my journey to understanding the painful beauty of grief, the value of the liminal space, and the essence of what it means to hold space for another person.

When Matthew was born, the nurses in the hospital handled it beautifully. They dressed him in tiny blue overalls and wrapped him in a yellow blanket, lovingly hand-made by volunteers. They took photos of him for us to take home, made prints of his hands and feet for a special birth/death certificate, and then brought him to my room so that we could spend the evening with him. I asked one of the nurses later how they’d known just the right things to do, and she told me that they used to be frustrated because they didn’t know how to support grieving parents, but then had all been sent to a workshop that gave them some tools that changed the experience for the parents and for them.

That evening, our family and close friends gathered in my hospital room to support us and to hold the baby that they had been waiting to welcome.

Now, nearly sixteen years later, I don’t remember a single thing that was said in that hospital room, but I remember one thing. I remember the presence of the people who mattered. I remember that they came, I remember that they gazed lovingly into the face of my tiny baby, and I remember that they cried with me. I have a mental picture in my mind of the way they loved – not just me, but my lifeless son. That love and that presence was everything. I’m sure it was hard for some of them to come, knowing what they were facing, but they came because it mattered.

This past week, I’ve been in a couple of conversations with people who were concerned that they might do or say the wrong thing in response to someone’s hard story. “What if I offend them? What if they think I’m trying to fix them? What if they think I’m insensitive? What if I’m guilty of emotional colonization?” Some of these people admitted that they sometimes avoid showing up for people in grief or struggle because they simply don’t have a clue how to support them.

There are lots of “wrong” things to do in the face of grief – fixing, judging, projecting, or deflecting. Holding someone else’s pain is not easy work.

In her raw and beautiful new book, Love Warrior, Glennon Melton Doyle talks about how hard it was to share the story of her husband’s infidelity and their resulting marriage breakdown. There are six kinds of people who responded.

- The Shover is the one who “listens with nervousness and then hurriedly explains that ‘everything happens for a reason,’ or ‘it’s darkest before the dawn,’ or ‘God has a plan for you.’”

- The Comparer is the person “nods while ‘listening’, as if my pain confirms something she already knows. When I finish she clucks her tongue, shakes her head, and respond with her own story.”

- The Fixer “is certain that my situation is a question and she knows the answer. All I need is her resources and wisdom and I’ll be able to fix everything.”

- The Reporter “seems far too curious about the details of the shattering… She is not receiving my story, she is collecting it. I learn later that she passes on the breaking news almost immediately, usually with a worry or prayer disclaimer.”

- The Victims are the people who “write to say they’ve hear my news secondhand and they are hurt I haven’t told them personally. They thought we were closer than that.

- And finally, there are “the God Reps. They believe they know what God wants for me and they ‘feel led’ by God to ‘share.’”

These are all people who may mean well, but are afraid to hold space. They are afraid to be in a position where they might not know the answer and will have to be uncomfortable for awhile. Wrapped up in their response is not their concern for the other person but their concern for their own ego, their own comfort, and their own pride.

It’s easy to look at a list like that and think “Well, no matter what I do, I’ll probably do the wrong thing so I might as well not try.” But that’s a cop-out. If the person living through the hard story is worth anything to you, then you have to at least show up and try.

From my many experiences being the recipient of support when I walked through hard stories, this is my simple suggestion for what to do:

Be fully present.

Don’t worry so much about what you’ll say. Yes, you might say the wrong thing, but if the friendship is solid enough, the person will forgive you for your blunder. If you don’t even show up, on the other hand, that forgiveness will be harder to come by.

So show up. Be there in whatever way you can and in whatever way the relationship merits – a phone call, a visit, a text message.

Just be there, even if you falter, stumble, or make mistakes. And when you’re there, be FULLY present. Pay attention to what the person is sharing with you and what they may be asking of you. Don’t just listen well enough so that you can formulate your response, listen well enough that you risk being altered by the story. Dare to enter into the grit of the story with them. Ask the kind of questions that show interest and compassion rather than judgement or a desire to fix. Risk making yourself uncomfortable. Take a chance that the story will take you so far out of your comfort zone that you won’t have a clue how to respond.

And when you are fully present, your intuition will begin to whisper in your ear about the right things to do or say. You’ll hear the longing in your friend’s voice, for example, and you’ll find a way to show up for that longing. In the nuances of their story, and in the whisperings they’ll be able to utter because they see in you someone they can trust, you’ll recognize the little gifts that they’ll be able to receive.

It is only when you dare to be uncomfortable that you can hold liminal space for another person.

This is not easy work and it’s not simple. It’s gritty and a little dangerous. It asks a lot of us and it takes us into hard places. But it’s worth it and it’s really, really important.

There’s a term for the kind of thing that people do when they’re trying to fix you, rush you to a resolution, or pressure you to have positive thoughts rather than fully experiencing the grief. It’s called “spiritual bypassing”, a term coined by John Welwood. “I noticed a widespread tendency to use spiritual ideas and practices to sidestep or avoid facing unresolved emotional issues, psychological wounds, and unfinished developmental tasks,” he says. “When we are spiritually bypassing, we often use the goal of awakening or liberation to rationalize what I call premature transcendence: trying to rise above the raw and messy side of our humanness before we have fully faced and made peace with it. And then we tend to use absolute truth to disparage or dismiss relative human needs, feelings, psychological problems, relational difficulties, and developmental deficits. I see this as an “occupational hazard” of the spiritual path, in that spirituality does involve a vision of going beyond our current karmic situation.”

When we’re too uncomfortable to hold space for another person’s pain, we push them into this kind of spiritual bypassing, not because we believe it’s best for them, but because anything else is too uncomfortable for us. But spiritual bypassing only stuffs the wound further down so that it pops up later in addiction, rage, unhealthy behaviour, and physical or mental illness.

Instead of pushing people to bypass the pain, we have to slow down, dare to be uncomfortable, and allow the person to find their own path through.

There’s a good chance that the person doesn’t want your perfect response – they want your PRESENCE. They want to know that they are supported. They want a container in which they can safely break apart. They want to know you won’t abandon them. They want to know that you will listen. They want to know that they are worth enough to you that you’ll give up your own comfort to be in the trenches with them.

Your faltering attempts at being present are better than your perfect absence.

My memory of that evening in the hospital room with my son Matthew is full of redemption and beauty and grace because it was full of people who love me. None of them knew the right things to say in the face of my pain, but they were there. They listened to me share my birthing story, even though there was no resolution, and they looked into the face of my son even though they couldn’t fix him.

Nothing was more important to me than that.

********

A note about what’s coming…

A new online writing course… If you want to write to heal, to grow, or to change the world, consider joining me for Open Heart, Moving Pen, October 1-21, 2016.

An emerging coaching/facilitation program… As I’ve mentioned before, I’m currently writing a book about what it means to hold space. While writing the first three chapters, I began to dream about what else might grow out of this work and I came up with a beautiful idea that I’m very excited about. I’ll be creating a “liminal space coaching/facilitation program” that will provide training for anyone who wants to deepen their work in holding liminal space. When I started dreaming of this, I realized that I’ve been creating the tools for such a program for several years now – Mandala Discovery, The Spiral Path, Pathfinder, 50 Questions, and Openhearted Writing. Participants of the coaching/facilitation program (which will begin in early 2017) will have access to all of these tools to use in their own work, whether that’s as coaches, facilitators, pastors, spiritual directors, hospice workers, or teachers.

If the coaching/facilitation program interests you, you might want to get a head start in working through one or more of those programs so that you’ve done some of the foundational work first. The more personal work you’ve done in holding space for yourself first, the more effective you’ll be in the work. (Participants in any of those courses will be given a discount on the registration cost of the coaching/facilitation program.)

*******

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my bi-weekly reflections.

by Heather Plett | Jun 13, 2016 | family, Uncategorized

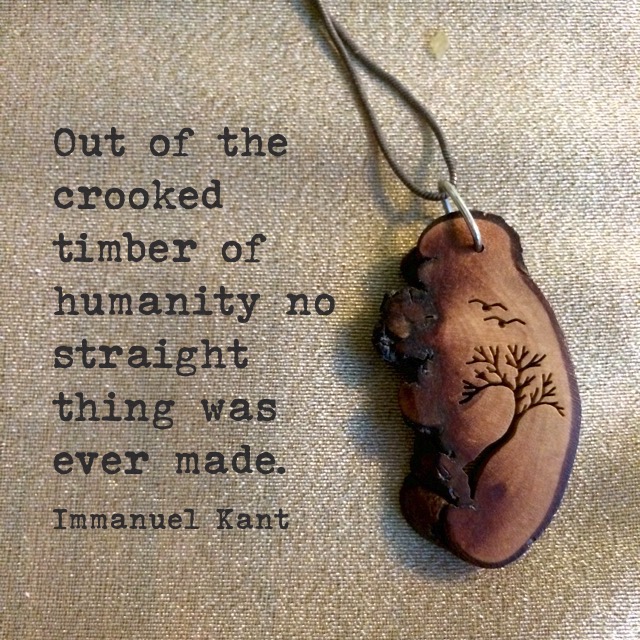

I have been contemplating the above quote ever since I heard it on the radio yesterday. We are, all of us, products of the “crooked timber of humanity”. None of us has ever emerged perfectly straight.

Before being shaped and carved by the woodworker’s tools – life’s chipping and sanding away of our imperfections – we are all irregular, imperfect, and unfinished branches of the crooked timber of humanity. Even after the shaping, our imperfections continue to show, but we learn to cherish rather than hide them.

I have a beautifully carved necklace made from a slice of a branch (see photo at the top – made by Windy Tree). What I like best about it is the way the artisan incorporated the imperfections of the branch, turning it into the rugged edge of a cliff out of which a tree grows.

Last weekend, I had the pleasure of spending a few days with those closest to me on my crooked family tree. My three siblings and I took a trip down memory lane together, visiting our childhood haunts in the rural part of the province where we grew up. We drove past the high school we all attended and talked about our favourite and least favourite teachers. We ate lunch in the Chinese restaurant that’s been there as long as any of us can remember. We played on the swinging bridge that crosses the White Mud River where we all took swimming lessons and were baptized as teenagers. We stopped to see the cairn that was erected at the place where our elementary school once stood.

Our parents are both buried in a graveyard on a sandy ridge close to our home town, under the towering poplar trees. As we stood near their graves, we marvelled at the fact that they are really and truly gone, that we are forever orphans, that they are part of our past and not our future. Though we are all near or past 50, it still feels far too young to have lost both of our parents. Perhaps one never feels old enough for that kind of loss.

Our last visit was to the farm where we grew up. We moved there when I was one year old and Mom and Dad moved away after we’d left home and my brothers and I were all about to welcome our first babies. That farmyard holds a lot of our family’s stories.

As we walked around the now-dilapidated farmyard, we reminisced about all that we’d lived through on that piece of land.

“This is where Grandpa collapsed and died on our lawn.”

“See that concrete pad? That was the front doorstep of the tiny green house we first lived in when we moved here, before we built the new house.”

“This is where we had to drag cattle out of the water that one Spring when there was so much flooding. Oh how we hated Dad when he came to wake us up in the middle of the night because another cow was stuck.”

“We used to climb into the rafters of this barn to find the new kittens.”

“What was that Low German word Dad would use when we were helping him build the steel bins and he wanted us to know a bolt was tightened and we should move to the next one?”

“Mom would have loved to have seen all of these lilacs she’d planted so fully grown and in full bloom.”

“Remember all those times when Dad had to climb down into the well to prime the pump and we stood at the top praying that he’d make it out safely?”

What emerged, as we peeked into broken-down barns and climbed over discarded fence posts, was how harsh and beautiful our childhood on that farm was. Some of our memories still held a touch of the pain those moments had caused. Others were pure joy. Some of them brought back old resentments of the decisions our parents had made. Others honoured them for their courage and resilience.

We were poor and life was often really hard on the farm. We hovered on the verge of bankruptcy and sometimes the phone was cut off or creditors would show up on the yard. Some of our hard luck was due to sandy soil, harsh weather, and the myriad of things that make crops fail or animals die. But some of it could be attributed to our parents’ poor choices and lack of business sense.

And then there were the other things not related to money that were hard – Dad’s anger and impatience, Mom’s way of over-apologizing and never believing she was good enough.

Our parents were imperfect – products of the “crooked timber of humanity”. They made mistakes. They let us down. They made us angry sometimes.

But that’s not the whole story. They were also full of goodness. They taught us how to love. They modelled integrity and morality. They made sure our home was always safe. They made sacrifices on our behalf. Dad taught us to love learning and Mom taught us to love stories.

Harshness and beauty. Kindness and anger. Insecurity and compassion. Poverty and abundance. All mixed together in one imperfect family.

My daughters will some day gather, after my death, to similarly reminisce. They’ll talk about some of the hurt they carried because of me, but they’ll also talk about the deep way I loved them. Because above all, I love them, just as my parents loved me.

And in the end, we must believe that love wins. And imperfection is less important than love.

We are put on this world not to seek perfection, but to learn grace.

We are put here to learn to make beautiful things out of imperfect branches.

We are put here to discover our own resilience and courage even as we hold our pain.

We are put here to love, to forgive, and to persevere.

One of the questions I ask my coaching clients, when they talk about people in their lives who are challenging, is: “How is that person your teacher?” Everyone – those who love us and those who hate us and those in between – can teach us something.

Not everyone in our lives will be good to us and not everyone will have our best interests at heart. Some of you may, for example, have had much more horrible parents than I had and you’ll be struggling at the end of this article to find any good in them or to forgive them for what they did. When I say that “we are put here to love and forgive”, I do not mean that we are meant to put up with all of the harsh treatment that comes our way.

No. That’s not it. You can learn to love with boundaries. You can end relationships that cause you great harm – even with your parents.

BUT, even the people who hurt us can serve as our teachers. Perhaps they teach us to respect ourselves more and not let them treat us that way. Perhaps they teach us our own courage. Perhaps they teach us boundaries. Perhaps they teach us forgiveness with detachment.

Instead of seeking perfection in others or yourself, seek for the lessons each relationship teaches you. Seek for the ways that you can grow because another person has been part of your life. Seek for the pinpoints of grace. Seek the piece of art that emerges from the imperfect branch.

I am writing this newsletter, once again, from my perch in the limbs of the large tree in my backyard. I am surrounded by crooked limbs, and I am grateful for the way their crookedness carved out this space that so perfectly cradles my body. I’m grateful for the smaller crooked limb that juts out at a strange angle that’s perfect for propping up my laptop. I am grateful for the canopy of crooked limbs that spread out above me, giving me shade from the sun’s heat.

Straight limbs are over-rated, especially in family trees.

p.s. If you need to talk to someone about your own crooked family tree and the ways that people serve as your teachers, perhaps I can help. I’m taking on a few new coaching clients.

ALSO, please consider joining me in Australia later this year. I’ll be hosting two retreats (Writing with an Open Heart and Living with and Open Heart) at Welcome to The BIG House. Early-bird registration ends at the end of June.

by Heather Plett | Dec 26, 2015 | grace, gratitude, grief, growth

I am writing from the shores of the Gulf of Mexico. I’ve come here with my family of origin – my three siblings, their spouses, and all of our children. I’m currently sitting on the patio of the large house we rented, just feet away from the pool. I can hear the waves crashing on the shore on the other side of the fence.

Three years ago, Christmas, for our family, was a painful time. We’d lost Mom only a month before and we were all raw and wounded and the festivities all around us were like slaps in the face every time we left the house.

We’re less raw this year, but the grief is never fully gone.

After Mom died, we decided to use the small inheritance that was left, after all of the expenses were paid, for a family vacation. We started dreaming of a week in the sun together… and then we got walloped all over again when my oldest brother was diagnosed with cancer only six months after it took Mom.

The next sixteen months were again mixed with the same highs and lows we’d been through with Mom’s cancer. Sometimes we dared to hope Brad would survive, and sometimes we were almost certain he wouldn’t. In August of last year, when the cancer showed itself to have survived two surgeries and mutliple chemo treatments, the doctors said there was no longer any point in prolonging treatment. We tried to prepare ourselves for another loss. Expecting we would have him with us for no more than 3 months, the four siblings considered going on a smaller version of the family trip we’d imagined – just the four of us making one last attempt to have fun in an interesting location before our numbers shrunk.

But then, the pendulum swung back in the other direction. The doctors decided it was worth making one more attempt at saving his life, so they cut him open again, extracted more cancer, and hoped for the best. That was shortly before last Christmas. We spent that season in subdued hope that he would stay with us and that we’d have more holiday seasons together. His energy was low, and he couldn’t travel, so the rest of us drove across the prairies to be with him instead of the other way around.

Over the course of the year, things continued to improve, and his remission continues. For now. Today is what we have, so today is what we will celebrate.

This week, we took that celebration to the shores of the Gulf. Three years after she died, we finally unwrapped Mom’s final gift.

On Christmas Day, the four of us spent all afternoon playing like children in the giant waves. Spouses and children joined us for awhile, but the four of us stayed in the water by far the longest. We relished every wave and held every burst of laughter like a sacred jewel. Some waves tossed us to the ground, some buried us and left us gasping for air, and some let us simply roll gently over the top. Long after we were so weary we could barely stand, we played and laughed, hanging onto every moment as though it were our last.

At one point, in a short lull between waves, one of us remarked that this moment represented all that was left of the tiny pittance of money mom and dad had left after all of their years of toiling on the farm. Farming was hard on all of us, and in the end it killed our dad, but it also gave us many incredible gifts, including this moment.

This trip has been both grace and gift in the middle of all of our shared grief.

And that is the way of life. We walk through grief and then we step into grace, over and over again. There are moments of profound loss, and moments of ache and betrayal, and then there are moments when we play for hours in the waves with three of our favourite people in the world.

Earlier this week, on a long solitary walk on the beach, I was contemplating what my word for 2016 would be. Unlike a resolution, I consider my word for the year like an invitation or intention – something that helps me stay open for my own longings and the gifts that come my way.

The word that came to me was OPEN.

I want to live 2016 with an open heart. I want to be open to the gifts, the grace, and the grief. I want to open myself to new relationships, new experiences, and new learning opportunities.

I want to stay open the way I felt out there on the waves – surrendering to whatever gift each one brought – riding those that were gentle, rising up again after those that were not, and always laughing and hanging onto to those people who matter.

Soon we will begin to return to our various homes. We may have another chance to play together like this, or we may not. Only God knows our future. But in the meantime, we have this moment, and in this moment I make a conscious choice to remain open.

Note: If you want to choose a word for 2016, or if you want to reflect on the gifts, grace, and grief that 2015 has brought your way, there are mandala exercises for that purpose in A Soulful Year: A mandala planner for ending one year and welcoming the next.

Also: Mandala Discovery starts on January 1st.

by Heather Plett | Nov 25, 2015 | Beauty, change, Community, Compassion, connection, Friendship, grace, growth

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the importance of finding your tribe – people who love you just the way you are and who cheer you on as you do courageous things.

Tribe-building is important and valuable, but it only takes you part way down the path to an openhearted life.

This week, I’ve been contemplating what we should do with the people outside of our tribes.

It’s cozy and warm inside a tribe, and the people are supportive and non-threatening, so it’s tempting to simply hide there and close off from the rest of the world. When you’re hurting, that might be the right thing to do for awhile – to protect yourself until you have healed enough to step outside of the circle.

But the problem with staying there too long is that it creates a world of “us and them”. When you stay too close to your own tribe, it becomes easier and easier to justify your own choices and opinions and more and more difficult to understand people who think differently from you. Before long, you’ve become suspicious of everyone outside of your tribe, and when their actions threaten your way of life, you do whatever it takes to protect yourself. Fear breeds in a closed-off life.

Last week, I knew it was time to challenge myself to step outside my tribe. I’d been playing it safe too much lately, so when I saw a Facebook posting for an open house at the local mosque, I decided that was a good place to start. I shared the information with friends, but chose not to bring anyone with me. Bringing friends with me into unfamiliar territory makes me less open to conversations with people who are different from me and I didn’t want that – I wanted to go in with an open, unguarded heart. That’s one of the reasons I’ve learned to love solo traveling – it’s scary at first, but it opens me to a whole world of new opportunities and friendships that don’t happen as naturally when I’m hiding behind the safety of a group.

I have traveled in predominately Muslim parts of the world and have always been warmly received, so I knew that the open house would be a pleasant experience. It turned out to be even more pleasant than I’d expected.

First there was Mariam, a young university student who served as tour guide to me and a small group of strangers. Mariam’s easy smile and warm personality made us all feel instantly comfortable. She lead us through the gym to the prayer room and told us why she’s happy that the women pray in a separate area from the men. “I want to be close to God when I pray, not distracted by who might be looking at me or bumping into me.” Before the tour was over, Mariam hugged me twice and I felt like I’d made a new friend.

First there was Mariam, a young university student who served as tour guide to me and a small group of strangers. Mariam’s easy smile and warm personality made us all feel instantly comfortable. She lead us through the gym to the prayer room and told us why she’s happy that the women pray in a separate area from the men. “I want to be close to God when I pray, not distracted by who might be looking at me or bumping into me.” Before the tour was over, Mariam hugged me twice and I felt like I’d made a new friend.

Then there was the grinning young man at the table by the sign that read “your name in Arabic”. His name now escapes me, but I can tell you he never stopped smiling through our whole conversation and was one of the friendliest young men I’ve met in a long time. He told me, while he wrote my name, that he’d learned some of his Arabic from cartoons. Growing up in Ontario, he’d preferred Arabic cartoons to Barney or Sesame Street.

At the “free henna” table, I met Saadia, who moved here from Pakistan three years ago because she and her husband wanted to give their children a better chance at a good education. Her husband is a doctor who’s still trying to cross all of the hurdles that will allow him to practice in Canada. Before our conversation was over, Saadia had given me her phone number in case I ever want to invite her to my home to give me and my friends hennas.

What struck me, as I left the mosque, was how much grace and courage it takes, when your people have become the object of racism, fear, and oppression, to open your hearts, homes, and gathering places to strangers. Instead of hiding within the safety of their own tribe and justifying their need for protection and safety from others, the local Muslim community threw their doors and hearts open wide and said “let’s be friends. We are not afraid of you – please don’t be afraid of us.”

I experienced the same grace and courage among the Indigenous people of our community last Spring after we were named the “most racist city in Canada”. Instead of retreating into the safety of their tribes, they welcomed many of us into openhearted healing circles. Instead of being angry, they taught us that reconciliation starts with forgiveness and the courage to risk friendships across tribal lines.

I will be forever grateful to Rosanna, who invited me to co-host a series of meaningful conversations with her, to Leonard who handed me a drum and welcomed me to play in honour of Mother Earth’s heartbeat, to Gramma Shingoose who gave me a stone shaped like a heart and shared the story of her healing journey after a childhood in residential school, to Brian who welcomed me into the sweat lodge, and to many others who opened their hearts and reached across the artificial divide between Indigenous and settler.

The more I’ve had the privilege of building friendships with openhearted people whose world looks different from mine, the bigger, more beautiful, and less fearful my life has become.

This week, I’ve read Gloria Steinem’s memoir, My Life on The Road and there is so much in it that resonates with the way I choose to live my life. It’s a beautiful reflection of how her life has been changed by the people she has encountered while on the road. “Taking to the road – by which I mean letting the road take you – changed who I thought I was. The road is messy in the way that real life is messy. It leads us out of denial and into reality, out of theory and into practice, out of caution and into action, out of statistics and into stories – in short, out of our heads and into our hearts. It’s right up there with life-threatening emergencies and truly mutual sex as a way of being fully alive in the present.”

Another quote speaks to how much broader her thinking has become because of her encounters on the road. “What we’ve been told about this country is way too limited by generalities, sound bites, and even the supposedly enlightened idea that there are two sides to every question. In fact, many questions have three or seven or a dozen sides. Sometimes I think the only real division into two is between people who divide everything into two and those who don’t.”

We don’t have to spend as much time traveling as Gloria Steinem does in order to live this way – we simply have to open our hearts to the people and experiences in our own communities that have the potential to stretch and change us and lead us past a life with only two sides. Sometimes a conversation with the next door neighbour is enough to help us see the world through more open eyes.

* * * * *

p.s. Would you consider supporting our fundraiser to sponsor a Syrian refugee family?

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Dec 29, 2014 | Creativity, grace, gratitude, grief, growth, mandala, Uncategorized

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.” ― Søren Kierkegaard

Last year, as the year ended, I shared a special mandala prompt for reflecting on the passing year before you invite in the new year. In that prompt, you were invited to divide your circle into 4 quadrants, with the words “grace, grief, growth, and gratitude” in each of the four quadrants. Then, with some reflection of the year that had passed, you filled each of the four quadrants with the things that happened that were connected to those four words.

Last year, as the year ended, I shared a special mandala prompt for reflecting on the passing year before you invite in the new year. In that prompt, you were invited to divide your circle into 4 quadrants, with the words “grace, grief, growth, and gratitude” in each of the four quadrants. Then, with some reflection of the year that had passed, you filled each of the four quadrants with the things that happened that were connected to those four words.

The process of filling those four quadrants helps you see the year for ALL that it was, not just the happy things and not just the hard things. Sometimes we get stuck in only one story and we assume that that story defines us, but each of us walks through many stories and each of those stories teaches us something. Life is never a perfect balance, but it’s also never only one of those four things.

That reflection mandala is now a part of A Soulful Year: A Mandala Workbook for Ending one Year and Welcoming Another. Before you begin the process of planning for what’s ahead, it’s valuable to reflect on what has passed and on what those events have taught you.

The Reflection Mandala is a useful process to do every year at this time. Take some time this week to create your own simple four quadrant mandala for 2014. Many of us have kept gratitude journals, and that is a beautiful practice that has been transformational in my own past, but sometimes that’s not enough. This practice offers an extension of that, where focusing not only on the gratitude, but on the grief and growth and what may have been really hard to walk through helps us recognize all of the complexity of our lives and all of the things that change us and stretch us.

Here’s an idea for extending the practice of reflecting on grace, growth, gratitude, and grief throughout the year…

Reflection Jars

Find, buy, or make four containers that you can keep on your desk, bookshelf, or nightstand. (I purchased 4 small jars at the dollar store for $2.)

Write (or print stickers, as I did) the words grace, grief, gratitude, and growth on each of the containers. Embellish the containers however you wish.

Cut up small pieces of paper that you can keep in an envelope close to your containers.

On a regular basis throughout the year (daily or weekly), reflect on how grace, grief, gratitude, and growth have been present for you. Write notes on slips of paper and slip them into which ever jar that reflection belongs in. You can do all four each day, or just do the ones that most apply to that day. Try to maintain a reasonable balance, filling each jar instead of focusing on only one.

Here are some prompts for the four categories:

Gratitude

This one is simple – what are you grateful for today? What made you happy? Who showed love or compassion? What did you have fun doing?

Grace

A simple definition of grace is “anything that shows up freely and unexpectedly that you did nothing to earn”. It can be a beautiful sunset that catches you by surprise as you’re driving home, an unexpected kind gesture from a friend, or forgiveness that you don’t feel like you deserve. What was unexpected and unearned? How did the beauty of the world stop you in your tracks? How did friends extend undeserved forgiveness or offers of help?

Grief

What made you sad? Who do you miss? What feels broken? What old wounds are showing up? What did you lose? What disappointed you?

Growth

What stretched you? What did you learn? What were your a-ha moments? Who served as your teacher? How did you turn hard things into opportunity for growth?

Fill your jars with meaning throughout the year.

It’s quite possible that some items will show up in multiple jars. For example, something that causes grief will probably also offer you opportunities to grow. And sometimes (like when friends show up to support you) grace shows up in the darkest of moments.

It’s quite possible that some items will show up in multiple jars. For example, something that causes grief will probably also offer you opportunities to grow. And sometimes (like when friends show up to support you) grace shows up in the darkest of moments.

Keep the containers in a place where they’ll be visible and easy to access and where you’ll remember to fill them up. You might want to do this as a morning practice before you start your day or an evening practice as you reflect on the day that passed.

At the end of the year, create a new four-quadrant mandala, take all of the pieces out of the jars and write or glue them onto the mandala. Reflect on your well-balanced year.

Start filling the jars again next year.

Once you’ve reflected on the year that passed, you may want to continue with a variety of other processes that will help you welcome and plan for what wants to unfold in 2015. A Soulful Year may help.

If you’d like to receive a mandala prompt every day in January 2015, consider signing up for Mandala Discovery.