by Heather Plett | Sep 5, 2016 | journey

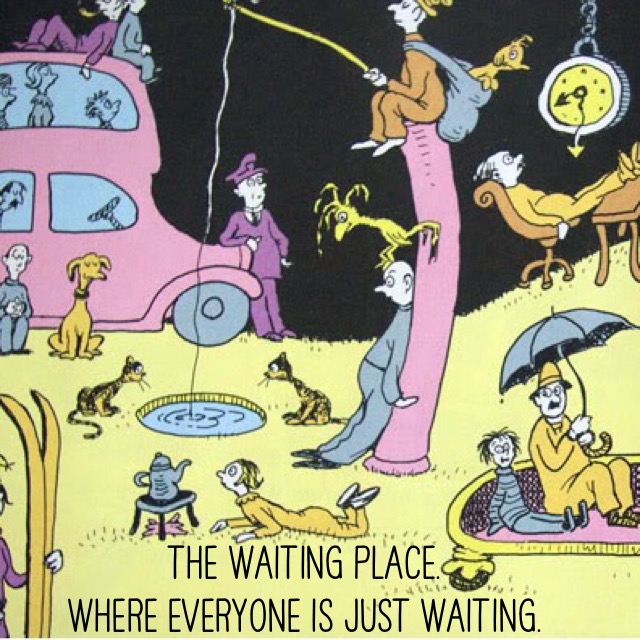

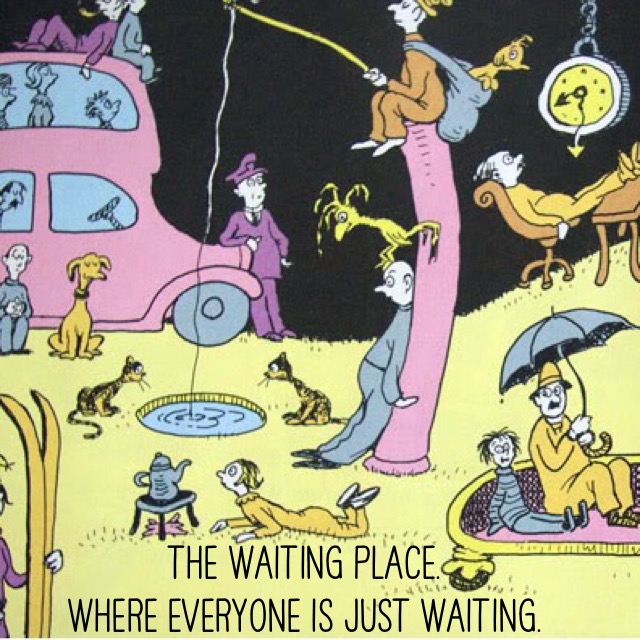

Sometimes, when you’ve read too many deep thinkers and thought too many deep thoughts, you just have to go back to Dr. Seuss for some clarity. While writing the first three chapters of my book on holding space in the last few weeks, I was puzzling over how to describe liminal space. I finally went back to this…

You can get so confused

that you’ll start in to race

down long wiggled roads at a break-necking pace

and grind on for miles cross weirdish wild space,

headed, I fear, toward a most useless place.

The Waiting Place…

…for people just waiting.

Waiting for a train to go

or a bus to come, or a plane to go

or the mail to come, or the rain to go

or the phone to ring, or the snow to snow

or waiting around for a Yes or No

or waiting for their hair to grow.

Everyone is just waiting.

In the first chapter of the book, I wrote about the liminal space we were in when we were expecting Mom’s death (an expansion of the blog post that was the catalyst for this book). Mom was in that liminal space herself (not quite dead, but no longer quite alive) and we were in that space with her) not quite bereaved and yet no longer able to participate in full relationship with her).

Inspired by Dr. Seuss, I wrote my own version…

We were waiting.

Waiting for her breath to change

or the pain to come

or the song to end

or the light to change

or the birds to visit

or the night to come

or the nurse to say “it’s almost over”.

Just waiting.

Ironically, (or perhaps serendipitously), while I’ve been writing these chapters, I’ve been in another kind of Waiting Place. This time, I am “not quite divorced and yet no longer in a marriage”. It’s been a summer of waiting. Waiting for divorce lawyers to draw up separation papers, waiting for the bank to clear the mortgage, waiting for the real estate lawyer to draw up new papers for the house, waiting for the land transfer title to go through so that I own the house. Each waiting period has been compounded with at least one of the parties involved going on vacation, so what should have taken a few weeks has dragged on for six months.

Last winter, I decluttered and repainted the interior of my house. Anticipating the new flooring that we badly need, I moved all of the living room furniture into the garage before painting. But then it took months longer than I expected to push all of the paperwork through, so the floors still aren’t finished and the furniture is still in the garage. My living room, quite literally, feels like The Waiting Place. (In fact, a friend dropped in to pick something up and thought she had the wrong place because it looked like we’d moved out.) “Waiting for the bank to call. Waiting for the lawyer to return from a month-long vacation. Waiting for the old carpet to be torn out. Waiting for the furniture to be moved back in. Everyone is just waiting.”

It’s been frustrating and what little patience I had at the beginning of the summer has been stretched to the limit. A person can only take so much of The Waiting Place. It’s been wreaking havoc with my emotions, bringing up old fears and frustration, and getting in the way of my most important relationships.

Finally, today, I decided it was time to do what I tell my coaching clients to do when they’re in the liminal space between what was and what is yet to come – stay present for what’s right now, find the tools and practices that help with processing, and open myself to what wants to emerge out of the liminal space.

For the first time in a long time, I took out my mandala journal and created a new mandala for the liminal space. It helped. Here’s a mandala journal prompt that I created out of my own process…

Liminal Space – a mandala journal prompt

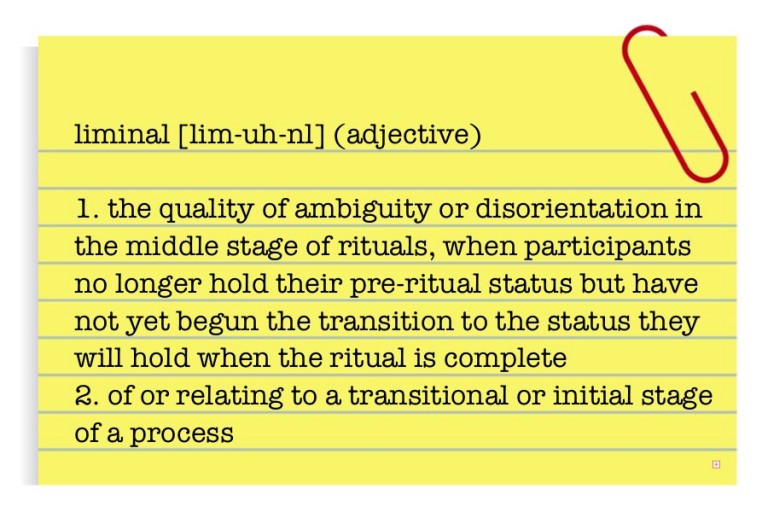

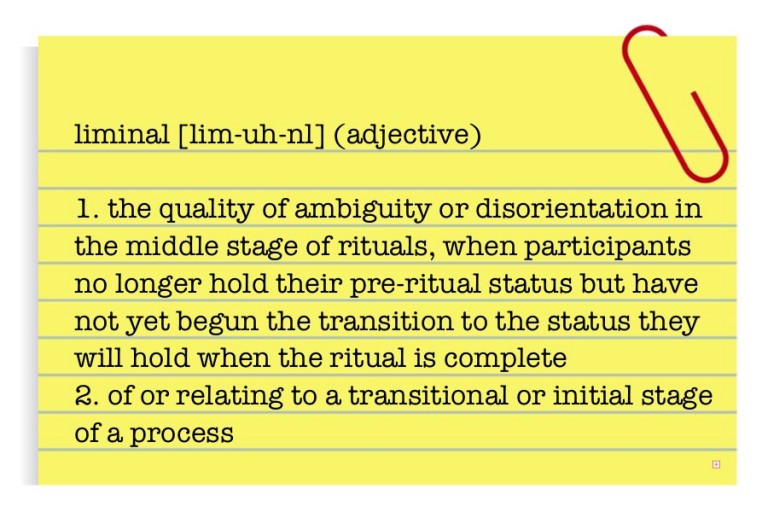

In anthropology, a liminal space is a threshold. It’s an ambiguous space in the middle stage of rituals, when participants no longer hold their pre-ritual status but have not yet begun the transition to the status they will hold when the ritual is complete. That liminal space finds us between who we once were and who we are becoming. It’s disorienting, uncomfortable, and it almost always takes far longer than we expect.

Much like The Waiting Place in “Oh The Places You’ll Go“, it feels like “a most useless place”, but it’s not. It’s a time of hibernation, a time of transformation, a time of resting, and a time of deep learning.

Nobody teaches us more about liminal space than the lowly caterpillar. Not knowing why, and not having the capacity to imagine its future as a butterfly, a caterpillar knows only that it must surrender, shed its skin, create the shell of a chrysalis, and then dissolve into a formless, gel-like substance awaiting rebirth.

The liminal space is about surrender. It’s about releasing the caterpillar identity before we have the vision for the butterfly. It’s about falling apart so that we can rebuild. It’s about daring to go into the darkness so that we can, one day, emerge into the light. It’s about trusting Spirit to direct the transformation.

One of the most critical things that the caterpillar teaches us in its transformation is that we need the shell of the chrysalis to hold space for us when we fall apart.

We need a protective shell that holds us in our formless state. It keeps us safe in the midst of transformation. It protects us from outside elements so that we can focus on the important internal work we need to do. It believes in the possibility for us even before we have the capacity to believe it ourselves.

When we enter our own chrysalis, whether that is the waiting place of divorce, grief, pregnancy, job loss, career change, graduation, children moving away, or any number of human experiences, we must build our own chrysalises that hold the space for our transformation. Like a patchwork quilt, we stitch together the people or groups who hold space for us (family, friends, pastors, therapists, coaches, churches, sharing circles, etc.), the practices that help us hold space for ourselves (journaling, artwork, prayer, body work, meditation, etc.), and the spaces which make us feel safe for transformation (our home, the park, a church, etc.)

Mandala Prompt

1. Draw a large circle and a second slightly smaller circle inside it.

1. Draw a large circle and a second slightly smaller circle inside it.

2. At the centre of the mandala, glue or draw an image or words that represent the liminal space. (I used an image from The Waiting Place in “Oh, the Places You’ll Go”. Another idea might be an image of a chrysalis.)

3. In the space between the image and the next largest circle, write sentences, words, or phrases that represent what The Waiting Place is like. Explore your emotions, fears, resistance, etc., and also explore your wishes, your opportunities for learning, etc. You can use the following as prompts for starting your sentences:

– I feel…

– I am…

– I fear…

– I want…

– I will…

– I am learning…

– I wish…

(Note: I blurred mine in the image above, since it was a little too personal to share.)

4. Imagine that the outer rim (between the two outer circles) is your chrysalis. Inside the rim, write down all of the people who hold space for you, all of the practices that help you hold space, and all of the places you go when you need to hold space for yourself.

5. Colour/decorate your mandala however you wish. As you are doing so, set an intention for what you wish to invite in as you surrender to the chrysalis. For example, I whispered an intention for more patience and grace as I wait for the next story to emerge.

Want more prompts like this? Sign up for Mandala Discovery and you’ll receive 30 prompts on topics such as grief, fear, play, grace, community, etc.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my bi-weekly reflections.

by Heather Plett | Sep 16, 2015 | art of hosting, circle, Community, growth, journey

I’ve come to Sedona, Arizona, to work with a new client, holding space for what is emerging in an innovative and wholehearted business development process. The work is taking shape as we do it, and we are all opening ourselves to possibilities and new relationships.

Yesterday, I hosted the first circle process, inviting people to bring their stories and speak to the values and needs that will help create the container for the work that will be done here. After they’d shared, I talked about how we had each brought strengths to the circle, but we must also remember that we each brought weaknesses.

“I invite you to be brave enough to bring both your strengths and weaknesses into the circle,” I said. “It’s like a yin yang symbol – we are both the dark and the light, the strength and the weakness. We need both and we need each other. Our weakness creates a beautiful space in which others’ strengths can fill the gaps and make the circle more complete and balanced.”

Shortly after that, in a rather ironic twist, I modelled exactly what I’d been talking about. I didn’t do it willingly, though. I got sick – really sick. Not moving from the bed except to run to the bathroom kind of sick. Covering myself in three layers of blankets and still shivering kind of sick.

Suddenly, though I’m here to hold space for those doing the work here, the roles were reversed and they were holding space for me, bringing mint tea to settle my stomach, tylenol to bring down the fever, a bucket to keep beside the bed, and whatever else I needed.

I felt horrible – both physically and emotionally. I didn’t want to be the needy person here. I wanted to be the one caring for other people. The worst of it is that I had to tell these people who are mostly strangers to me that, if I begin to vomit, someone needs to rush into the room to catch me. You see, I have this horrible tendency to pass out and wake up on the floor when I vomit. So they brought me a bell (the same bell I’d just used to open the circle) and made me promise to ring it if I needed them.

At one point, with a couple of them in the room checking on me, I started to weep. I felt so vulnerable and was finding it hard to need them like this. And yet, I had no choice but to admit my vulnerability and receive their nurturing and care. Not once did they make me feel guilty or ashamed for needing it, but that didn’t stop me from feeling that way.

This morning, as I began the journey back to health, I had to smile at the irony that, though I had told all of them to admit their needs and let others fill them, I was reluctant to do the same. Some things are easier said than done.

Those of us who are used to bringing our strength into the room in order to hold space for others, often forget that we need to give others opportunities to hold space for us. It’s always a humbling experience when we’re the ones in need, but it’s not only good for us to be in a place of humility, it’s good for the collective circle when each of us balances our needs with our offerings.

“Ask for what you need and offer what you can,” says Christina Baldwin in The Seven Whispers. That’s what creates the balance, the yin and the yang of relationship.

Even those of us who teach this need to be reminded to put it into practice.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Sep 2, 2015 | growth, holding space, journey

Now that it’s September, I’m getting back into the rhythm of writing weekly reflections. This one’s fairly short.

I have a few more thoughts about holding space to share with you…

In the past six months, since my blog post went viral, I’ve done more than half a dozen interviews on the topic of holding space. The nice thing about talking about something so much is that I gain a deeper understanding every time I talk about it. Sometimes I say things I didn’t know I knew!

This week, I was doing an interview for an upcoming podcast, when I heard myself say this…

Sometimes the hardest thing about holding space is it can feel and look a lot like doing nothing.

When we’re holding space well, we’re keeping our ego out of it, not controlling the outcome, not giving unsolicited advice, and not taking people’s power away. That can feel a lot like doing nothing.

We all want to DO SOMETHING. When a friend, family member, student, or client is hurting, confused or overwhelmed, it’s really hard not to step in and fix the situation, offer resources, or give advice. Think about all of the food that people give away when someone is grieving – everyone wants something to do in response to the gaping void this person is feeling. Or think about the last time someone confided in you and your first instinct was to rush in and offer them something that might help.

I see it (and feel it myself) often when I host circles. When someone in the circle is crying, people lean in and really, really want to have something to offer – advice, other ways of framing the story, tissue, SOMETHING. But the practice in the circle is to remain silent and to listen with attention when someone else is holding the talking piece. And the greatest healing I have seen take place in the circle is when people feel genuinely and unconditionally listened to.

It’s true that often there are perfectly valid and practical things to do in response to someone else’s pain. I am eternally grateful for all of the people who brought food, looked after my dad’s farm animals, helped us prepare the farm for sale, etc., after Dad died, for example.

But just as often, people need our presence more than they need our actions or advice.

Giving people our presence can feel a whole lot harder than giving them our advice. It can make us feel vulnerable, useless, and unproductive. And yet, when I think back to the people who were the greatest support during my own difficult times, it was often those people who knew how to show up, listen deeply, withhold judgement, and trust me to know how to find my own path through it that were the most memorable. I remember people who showed up after my son died and simply sat there and held his lifeless body while we cried together. And I remember people who came when my husband was in the hospital who sat on park benches or in vehicles or coffee shops and let me talk or cry or scream. They said little and “did” less, but it was just what I needed.

I find the same thing in my work of hosting retreats and workshops. The ones that are the most successful are usually the ones in which I speak the least. When I give people gentle guidance and a safe container to do their own work, they get much more out of it than when I dump a lot of content on them. (The same can be said for parenting.)

This has been well modelled for me by my mentor, Christina Baldwin. At a recent writing retreat, we had a 24 hour silent, solitary, writing period. “I will be in the kitchen area all day, holding space for you,” said Christina. Ostensibly, she was “doing nothing”, and yet we all felt incredibly supported, knowing that she was there, gently holding us. While we did our deep work, we could trust that she was present for us, even though she never said a word. We also knew that the next day in the circle, she would hold the container while we talked about whatever came up.

The next time you’re inclined to do something in support of someone you care about, pause for a moment and consider what they really need. Is there a practical need you can fill, or would it be best to show up and offer deep listening, trust, and unconditional love?

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Aug 26, 2015 | childhood, growth, parenting

It all started in Maddy’s room. She’d been complaining for quite some time that she’d had to inherit a room decorated for her sisters when they were quite young and it was time for her to have a room fit for her own thirteen-year-old personality. After waffling between a Harry Potter themed room and pretty-in-pink, she chose a pale pink and we bought the paint. It made me smile when I applied it, because it was the exact opposite of what had happened when I was that age. I couldn’t wait to get rid of the pink in the little-girl bedroom I shared with my sister. In my mind, pink = girlie and girlie wasn’t cool, so the bedroom was painted blue.

Like many in my era, I was figuring out who I was in the face of the feminist movement, and instead of embracing what was feminine, I ran away from it and tried to prove I was worthy by being more masculine. It wasn’t until years later that I realized that a) pink is just a colour and has no inherent meaning, and b) to be whole and strong means to embrace what is feminine along with what is masculine.

The day we were choosing the paint, I overhead Maddy (who wears nothing but dresses) say to her friend, “Legally Blonde is my favourite movie because it shows that you can be both feminine and feminist at the same time.” I’m so glad she’s figuring that out earlier than I did.

My other two daughters are now 18 and 19 and though they’ll both be in university in the Fall, they’ll be staying home and studying locally for now. They were switching bedrooms (it was the 18 year old’s turn to have the bigger room in the basement), so it seemed like the ideal time to refresh their rooms as well.

In both cases, we transformed the rooms from their early-teen choices to their much more grown-up choices. The room in the basement (that had been Nikki’s and was becoming Julie’s) was four bright colours – blue, green, orange and yellow – and was now getting a much more subdued look – black, grey, and light teal-grey. The room upstairs was going from orange and green with huge contrasting polka-dots to a dark beige and white.

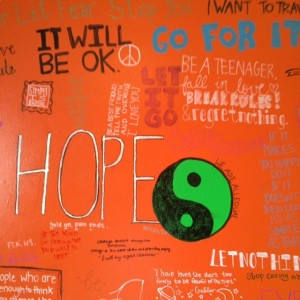

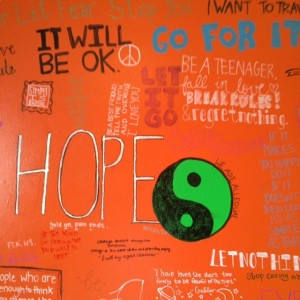

Julie’s former orange and green room presented us with the greatest challenge, not because of the boldness of the colours but because she had covered the walls with hundreds of quotes, thoughts, art, etc., in Sharpie marker.

I knew from previous experience that Sharpie marker is almost impossible to cover with paint, even with the very best primer, and yet, five years ago, when she’d asked if she could do it, I said yes. Julie has a gift for script-work and I knew it would be interesting, but more importantly, I had an intuitive sense that it was what she needed at the time.

I knew from previous experience that Sharpie marker is almost impossible to cover with paint, even with the very best primer, and yet, five years ago, when she’d asked if she could do it, I said yes. Julie has a gift for script-work and I knew it would be interesting, but more importantly, I had an intuitive sense that it was what she needed at the time.

The hardest year of Julie’s life so far was when she was thirteen and in grade 8. She’s a deep thinker and a deep feeler, and the world was too intense for her at the time. We watched her walk through a depression and we worried every single day about whether we were doing the right things to support her. When she started writing on the walls, I bought the Sharpie markers, hoping that turning her bedroom walls into a journal of her angst and attempts to rise out of that angst might be healing for her. It was.

Some of what was on the walls was quite angry (especially what she hid in the closet), some was quite hopeful, and all of it was a search for her own path and for meaning in a complex world. Like, for example, the giant word “HOPE” with the smaller words underneath “hold on pain ends”.

While we painted over the Sharpie markings last week, Julie thanked me for letting her do it. On an Instagram photo she posted, she said this: “Incredibly thankful to have the kind of parents who let their angsty 13 year old daughter put her art all over her walls, even if it involves buying $70 primer to cover it up 5 years later.”

Like any parent, I had no idea if we were doing the right thing at the time, and yet we did what we could. And now she has grown into a strong, articulate and wise 18 year old who was class valedictorian at her recent graduation and who won a scholarship for being a gifted writer. (Here’s a piece of her writing I once shared on my blog.)

A few insights emerged while I painted the walls last week, not just about parenting but about holding space for anyone going through their own personal growth. Parenting three daughters who each have unique (and surprisingly different) personalities is a great training ground for my coaching and facilitation work.

Here’s what I’m learning about holding space for people in the midst of their own personal growth:

1) Respect each person as an individual. No two people need exactly the same things at the same time. My other 2 daughters never wrote on the walls, but they need other things, and so we try to offer them what they need to help them through the rough spots. When I try to treat them all the same, I do them a disservice. For example, one is an introvert, one’s an extrovert and one is somewhere in between. They’re learning to recognize what they each need in order to replenish their energy.

2) Honour whatever place a person is in their own journey. Don’t expect someone else’s journey to look anything like yours. All three bedrooms are completely different from what they were and all of them reflect the places the girls are in right now (not five years ago and not five years in the future). There are choices in each bedroom that are different from the choices I might have made, but I’m not the ones occupying those spaces.

3.) Help people find their own right creative practices. During Julie’s depression, I tried to get her to do some of the things that help me through the darkness, but none of those things were right for her. I couldn’t take that personally because it wasn’t about me – it was about her. What worked for her was Sharpie markers and permission to make art on the walls.

4.) Don’t be afraid to let others take risks you wouldn’t take. I often marvel at how confidently Maddy embraces dresses and the colour pink. (At the same time, she also considered black skull-and-crossbone curtains – she is far from one-dimensional.) None of her friends wear dresses and I doubt whether any of them would choose the colour of paint she chose, and yet it’s what she likes and that’s all that matters.

5.) Give people a safe place to hide, to be themselves, to fail, or separate themselves from others. I am so glad that I had the privilege of giving each of my girls a beautiful new space to call their own. They are all learning to honour their own choices, their own sense of when they need to withdraw from the world, and their own boundaries. Those are powerful things to learn, especially for teenage girls navigating a world that places far too many expectations on them. Nikki, my most introverted daughter, loves to close the door to her room and listen to her record player alone, while her more extraverted sisters have been happy to invite friends over to enjoy their rooms with them.

I don’t often write posts about my daughters or about parenting, because their stories are their own and because most days I feel like I’m wandering around in the dark trying to feel my way through. But my parenting journey has taught me much about what it means to hold space for people on their own personal growth paths and I know that I am a better coach and facilitator for the lessons I’ve learned along the way. I can only hope that my daughters will continue to grow into strong, resilient, and courageous young women.

by Heather Plett | Jun 3, 2015 | change, circle, Community, Compassion, growth, journey, Leadership

“…whenever I dehumanize another, I necessarily dehumanize all that is human—including myself.”

– from the book Anatomy of Peace

This week, I’ve been thinking about how we hold space when there is an imbalance in power or privilege.

This has been a long-time inquiry for me. Though I didn’t use the same language at the time, I wrote my first blog post about how I might hold space for people I was about to meet in Africa whose socio-economic status was very different from mine.

I had long dreamed of going to Africa, but ten and a half years ago, when I was getting ready for my first trip, I was feeling nervous about it. I wasn’t nervous about snakes or bugs or uncomfortable sleeping arrangements – I was nervous about the way relationships would unfold.

I was traveling with the non-profit I worked for at the time and we were visiting some of the villages where our funding had supported hunger-related projects. That meant that, in almost every encounter I’d have, I would represent the donor and they would be the recipients. I was pretty sure that those two predetermined roles would change how we’d interact. My desire to be in authentic and reciprocal relationship with them would be hindered by their perceived need to “keep the donor happy”.

That challenge was further exacerbated by:

- a history of colonization in the countries where I was visiting, which meant that my white skin would automatically be associated with the colonizers

- my own history of growing up in a church where white missionaries often visited and told us about how they were working in Africa to convert the heathens

In that first blog post, I wrestled with what it would mean to carry that baggage with me to Africa. I ended the post with this… I won’t expect that my English words are somehow endued with greater wisdom than theirs. I will listen and let them teach me. I will open my heart to the hope and the hurt. I will tread lightly on their soil and let the colours wash over me. I will allow the journey to stretch me and I will come back larger than before.

In another blog post, after the trip, I wrote about how hard it was to find the right words to say to the people who’d gathered at a food distribution site…What can I say that is worthy of this moment? How can I assure them I long for friendship, not reverence?

That trip, and other subsequent ones to Ethiopia, India, and Bangladesh, stretched and challenged me. Each time I went, I wrestled with the way that my privilege and access to power would change my interactions. I became more and more intentional about entering into relationships with humility, grace, and openheartedness. I did my best to treat each person with dignity and respect, to learn from them, and to challenge my own assumptions and prejudice.

Nowadays, I don’t have the same travel opportunities, but I still find myself in a variety of situations in which there is imbalance. Sometimes I have been the one with less privilege and power (like when I used to work in corporate environments with male scientists, or when I traveled with and offered support to mostly male politicians). Other times, I have access to more power and/or privilege than others in the room (like when I am the teacher at the front of the classroom, or I am meeting with people of Indigenous descent). In each situation, I find myself aware of how the imbalance impacts the way we interact.

This week in Canada, the final report on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s findings related to Residential Schools has come out and it raises this question for all of us across the country. Justice Murray Sinclair, chair of the commission, has urged us to take action to address the cultural genocide of residential schools on aboriginal communities. Those are strong words (and necessary, I believe) and they call all of us to acknowledge the divide in power and privilege between the Indigenous people and those of us who are Settlers in this nation.

How do we hold space in a country in which there has been genocide? How do we who are settlers acknowledge our own privilege and the wounds inflicted by our ancestors in an effort to bring healing to us all?

This is life-long learning for me, and I don’t always get it right (as I shared after our first race relations conversation), but I keep trying because I know this is important. I know this matters, no matter which side of the power imbalance I stand on.

If we want to see real change in the world, we need to know how to be in meaningful relationships with people who stand on the other side of the power imbalance.

Here are some of my thoughts on what it takes to hold space for people when there is a power imbalance.

- Don’t pretend “we’re all the same”. White-washing or ignoring the imbalance in the room does not serve anyone. Acknowledging who holds the privilege and power helps open the space for more honest dialogue. If you are the person with power, say it out loud and do your best to share that power. Listen more than you speak, for example, or decide that any decisions that need to be made will be made collectively. If you lack power, say that too, in as gracious and non-blaming a way as possible.

- Change the physical space. It may seem like a small thing to move the chairs, to step away from the podium, or to step out from behind a desk, but it can make a big difference. A conversation in circle, where each person is at the same level, is very different from one in which a person is at the front of the room and others are in rows looking up at that person. In physical space that suggests equality, people are more inclined to open up.

- Invite contribution from everyone. Giving each person a voice (by using a talking piece when you’re sharing stories, for example) goes a long way to acknowledging their dignity and humanity. Allowing people to share their gifts (by hosting a potluck, or asking people to volunteer their organizational skills, for example) makes people feel valued and respected.

- Create safety for difficult conversations. When you enter into challenging conversations with people on different sides of a power imbalance, you open the door for anger, frustration, grief, and blaming. Using the circle to hold such conversations helps diffuse these heightened emotions. Participants are invited to pour their stories and emotions into the center instead of dumping them on whoever they choose to blame.

- Don’t pretend to know how the other person feels. Each of us has a different lived experience and the only way we can begin to understand what another person brings to the conversation (no matter what side of the imbalance they’re on) is to give them space to share their stories. Acting like you already know how they feel dismisses their emotions and will probably cause them to remain silent.

- Offer friendship rather than sympathy. If you want to build a reciprocal relationship, sympathy is the wrong place to start. Sympathy is a one-way street that broadens the power gap between you. Friendship, on the other hand, has well-worn paths in both directions. Sympathy builds power structures and walls. Friendship breaks down the walls and puts up couches and tables. Sympathy creates a divide. Friendship builds a bridge.

- Even if you have little access to power or privilege, trust that your listening and compassion can impact the outcome. I was struck by a recent story of how a group of Muslims invited anti-Muslim protestors with guns into their mosque for evening prayers. An action like that can have significant impact, cracking open the hearts of those who’ve let themselves be ruled by hatred.

- Don’t be afraid to admit that you don’t know the way through. Real change happens only when there is openness to paths that haven’t been discovered yet. If you walk into a conversation assuming you know how it needs to turn out, you won’t invite authenticity and openness into the room. Your vulnerability and openheartedness invites it in others.

- Don’t try this alone. This kind of work requires strong partnerships. People from all sides of the power or privilege divide need to not only be in the conversation, but be part of the hosting and planning teams. That’s the only way to ensure all voices are heard and all cultural sensitivities are honoured.

I welcome your thoughts on this. What have you found that makes a difference for conversations where there is an imbalance?

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

1. Draw a large circle and a second slightly smaller circle inside it.

1. Draw a large circle and a second slightly smaller circle inside it.