by Heather Plett | Mar 16, 2017 | Community, Compassion, connection

Melancholy: a feeling of pensive sadness, typically with no obvious cause

That sounds about right for my state of mind this past week. I hesitate to call it depression, because it doesn’t feel that heavy, but there is definitely “pensive sadness” going on and it has no obvious cause.

When this familiar sense of melancholy comes at this time of year, I usually chalk it up to the end of winter, when I’m a little more sluggish from not taking as many long walks in the woods and not getting as much sunshine as I need. I get a little imbalanced when I lose my connection to the natural world. I’m pretty sure that it will pass soon (Spring always revives me), but for now, my creativity is low, my resilience isn’t what it normally is, my emotions are a little tender, and I feel disconnected. I stare at blank pages when I should be writing, I crawl into bed earlier than usual, I cry unexpectedly, and I watch too much Netflix.

A couple of things happened last week that were quite minor, but because of my state of mind, I took them more personally than I normally would. Though none of the people involved meant any harm, my tenderness left me feeling a little lonely and a little rejected. There was no true rejection involved (I still feel well loved by them), but in the middle of my fragility, it’s always easier to make up stories that align with how I’m experiencing the world. Feelings of disconnection often lead to greater disconnection.

Not long ago, I was on the other side of that story, inadvertently wounding someone who was going through her own state of tenderness. Unaware of her emotional state, I said something that normally would have been received with ease, but instead carried some wounding.

“At two, you’re at abstraction.” That’s a line from a Sara Groves song (that I think she borrowed from someone else, but I can’t find the source) that points to the impossibility of fully understanding another person’s reality. Another person’s pain, joy, love, trauma, history – they’re all just abstract concepts for us because we have never lived inside of them. We can never really “walk a mile in another person’s shoes”.

Despite our best efforts to be compassionate and understanding, our well-meaning words can land the wrong way and leave a person feeling wounded, lonely, misunderstood, defensive, angry, etc. That’s one of the reasons why, in our efforts to hold space for other people, we need to avoid falling into the trap of taking responsibility for their emotional response to our words or actions. Each of us is a sovereign individual with our own stories, our own interpretations, and our own emotions and when we take too much responsibility for another person, we diminish their sovereignty.

At a workshop a few weeks ago, Dr. Gabor Maté talked about how trauma can shape a person’s world and change the way they respond to stimuli. When a person grew up with trauma (either in the form of a traumatic event, or as a result of being raised by caregivers with unresolved trauma) their fight/flight/freeze instincts are heightened and they are inclined to over-react to stimuli that brings them back to their traumatic memories. Unresolved trauma, he said, makes it impossible for us to be in the present moment. “When we’re triggered, the emotions that show up are those of the abandoned child. We don’t react to what happened – we react to our interpretation of what happened based in our traumatic memory.”

Even compassionate people can inadvertently trigger someone’s trauma. Think about the last time you said something to another person that you thought was fairly innocuous and they reacted with defensiveness or anger that seemed out of proportion for the moment. There’s a good chance that there was something in what you said that triggered an old wound that they may not even know they still have. In that instant, that person was not the mature adult you thought you were talking to – they were a scared child relying on an instinctual response for their own protection. While they may need your empathy in that moment, and you might make a mental note to adjust your behaviour in the future to avoid triggering them further, you can’t take their autonomy away by trying to fix their problem for them.

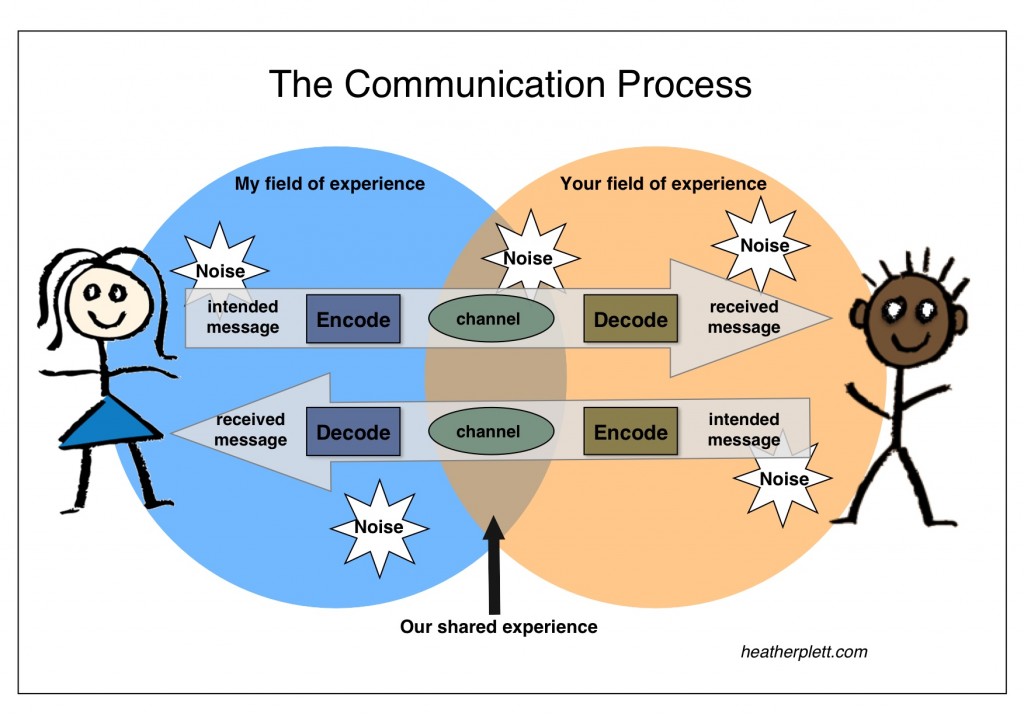

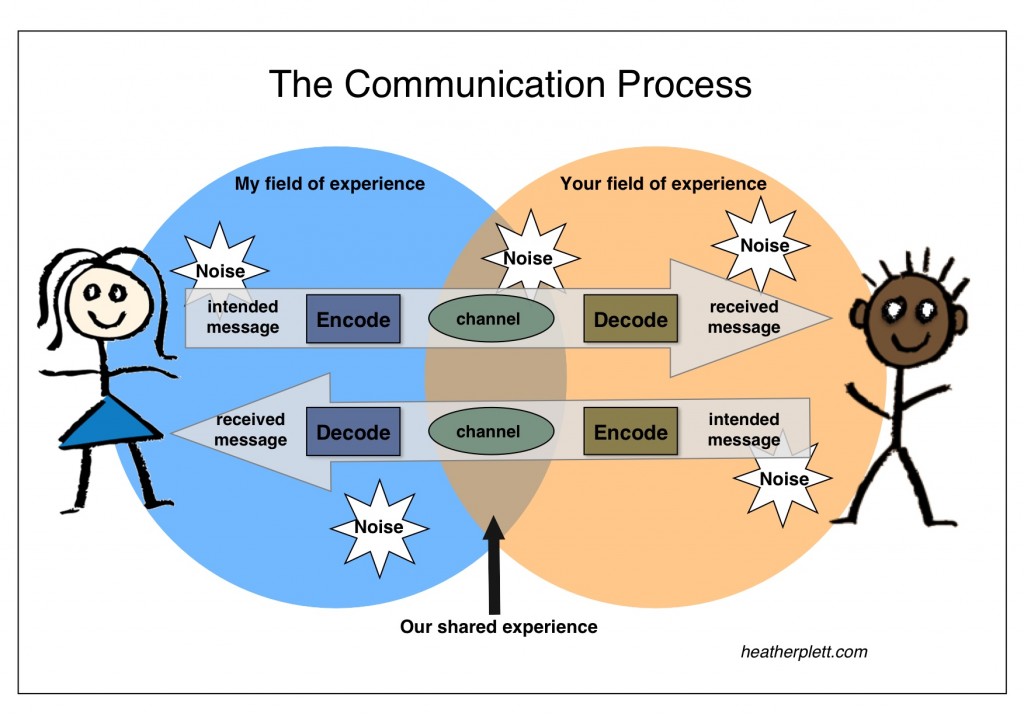

When I used to teach a university-level course in communication, I would always start with the following diagram to help my students understand that, in every communication, there are complexities and potential pitfalls that we can’t fully anticipate or mitigate.

(Note: this is my version of a popular model used in communication training, but I don’t know the original source.)

Each of us lives within a unique field of experience that may overlap with other people’s experience, but is never exactly the same. When I want to communicate with you, my intended message is shaped and encoded by my field of experience, which includes factors such as my gender, race, culture, disabilities, lived experiences, language ability, emotional state, etc.

I choose the channel of communication to best offer the message (ie. will I make a phone call, wait until I can talk to you in person, or send an email?). If I am compassionate, I will consider your field of experience when choosing the channel (ie. if you are hearing impaired, a phone call might not be the best method), but I’m limited in how much I can understand your reality so I may make mistakes. On top of that, no matter how carefully I encode the message and how intentional I am about the channel of communication, there is always unexpected noise that can disrupt or distract us at any moment in the process (ie. a child needing attention in the middle of a personal phone call, a disturbing story on the news, a misunderstanding, etc.).

The message crosses over to you and is, in turn, shaped and decoded by your own field of experience and your current circumstance. As I mentioned above, for example, you might be going through a period of tenderness that I had no way of knowing about when I initiated the communication. Even the most well-intentioned communication can go astray, and by the time you’ve decoded it, it may have a very different shape than what I intended. Much of our encoding and decoding processes happen in mere seconds during the course of a conversation, so we aren’t aware of all of what has shaped and reshaped what’s passed between us.

If you choose to engage in two-way communication, you send your own message across the reverse path, back through our fields of experience, risking similar misinterpretation, triggering, etc.

Given the potential complexity of even the simplest conversation, and given the fact that only a small portion of the process is within our control or within our conscious understanding, what can we do to improve the process? How can we be better communicators who wound others less often and receive fewer messages as wounds?

When you are the sender of the message:

• Pay attention to how your message is being shaped by your field of experience.

• Be humble, recognizing the limitation of your understanding of the other person’s field of experience.

• Especially where the differences are vast and there may be power imbalances, do your best to learn about the other person’s field of experience instead of passing judgement (especially if you are the one who holds more power).

• Be aware of the other person’s emotional response and check in when something doesn’t seem to land well, but don’t judge or try to control the emotion.

• Take responsibility for what you’ve said and allow the other person to take responsibility for their response.

• Allow for processing time in the conversation. Pauses may help to alleviate misunderstanding.

When you are the receiver of the message:

• Recognize the limitations that are at play in the sender’s lack of understanding of your field of experience.

• If you trust that the person will honour your current state of mind (ie. if there’s grief, depression, etc. going on), let them know that you may be limited in your capacity to receive.

• If you have a strong emotional response to the message, pause for a moment to check in with yourself. Recognize that the first reaction may be your instinctual desire to protect yourself and may not be fully based in the current situation.

• Hold the other person accountable for their words (especially in the case of harsh or oppressive language) and recognize when it may be in your best interest to stand up for yourself and/or walk away.

• If there is a misunderstanding and the relationship is important to you, reflect back to the person what your interpretation of the message is, based on your field of experience, and offer them an opportunity to reframe it.

• Take the time you need before sending a message back.

• Remember that you have a right to set boundaries and protect yourself.

Each situation is different, and based on how valuable the relationship with the other person is, you may or may not want to invest in the effort it takes to work through misunderstanding. If, for example, you’ve been verbally assaulted by a stranger at a bus stop, you probably won’t have any interest in figuring out how to communicate across your differing fields of experience. If, on the other hand, you love and trust the other person and believe that the relationship will be strengthened by deeper understanding, you’ll want to invest more time and energy in cutting through the noise.

*****

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my bi-weekly reflections.

by Heather Plett | Mar 1, 2017 | books

At the beginning of 2016, I made a commitment to read only books by authors who weren’t from the dominant culture. My intent was to broaden my education and stretch myself by staying away from books written by white able-bodied cisgender heterosexuals. Books have always helped me make sense of the world, and I knew that if I wanted to catch glimpses of the world through lenses that were different from mine, books would help me get there. Though my bookshelves reflect some diversity, I knew there was much more I could do.

It was harder than I expected. It’s not that there aren’t plenty of books by other voices – there are, but I had to dig harder to find them. It became clear, early on, that few publishers and booksellers are willing to bank on books by marginalized voices. They don’t invest in them as often and don’t put them front and centre in the bookstores. Walk through almost any bookstore (or at least those that I’m most familiar with, in North America), or browse through Amazon, and you’ll see fairly quickly what types of books get the most space and attention. Those voices that feel most “safe” for the average bookstore shopper will sell the most books, and I think it’s fairly safe to say that the “average bookstore shopper” is expected to be a white person with privilege.

That was one of my first realizations in this year-long quest… It is far more challenging to find a publisher and make a living from your writing if you do not fit the dominant paradigm. Other voices have to work twice as hard just to get a spot on the bookshelf. Like any other space ruled by capitalism, the bookstore centres those with privilege.

It was easiest to find books by marginalized voices in the fiction section, so I started there. Friends gave me lots of recommendation and my nightstand quickly filled with borrowed books. I started with Indigenous authors (in Canada, those are the voices that are often the most marginalized) and moved on to people of colour from the U.S., Africa, and Southeast Asia. Many of those books were gritty and challenging, and some of them brought up my white guilt. There were moments when I questioned why I was putting myself through this. Reading was starting to feel more like a chore and less like a pleasure. (Note: scroll down for a list of some of the books I read.)

Though I enjoy fiction, I don’t read nearly as much of it as I used to, and soon found myself searching for the kinds of books I lean toward – memoirs, books about the human condition, cultural exploration, leadership books, and other non-fiction. These became increasingly more difficult to find. Memoirs were fairly plentiful, once I started digging deeper than the typical bookstore shelves (and I found some great ones by writers who gave me a new perspective on what it means to be gender non-binary, what it’s like to be raised by a residential school survivor, etc.), but the hardest to find were the non-fiction books I tend to read that are relevant for my work.

I’m not sure how to define the books I most love to read, because they don’t tend to fit bookstore categorization. I read a lot of “ideas and culture” books – on leadership, spirituality, feminism, trauma, engagement, facilitation, personal development, etc. When I turned my attention to these books, my quest became the most challenging. Very few of these books are written by people who aren’t from the dominant culture.

And this was my second major realization in this quest… While we may be willing to read fiction, and sometimes memoirs by people who don’t look like us, we very rarely will accept as experts anyone who doesn’t fit the dominant paradigm. This is where the white, able-bodied, heterosexual, cis-gender voice is the most centred. Storytelling may have become a more equal playing field, but the fields of knowledge and expertise are still colonized by those with more power and privilege. And the higher you go up the “knowledge food chain” the more white women are eliminated as well.

In the Spring of 2016, just when I was looking for more of these kinds of books, something happened in my personal life that derailed my year-long commitment and made the absence of these voices even more obvious. As I’ve written before, I hit burnout. A combination of stresses in my life – divorce, single parenthood, home renovations, and the continued high demands that followed my viral blog post – left me feeling wobbly and exhausted. I stepped off social media, pulled away from some of my commitments, and sought therapy to help me get my feet back on the ground.

As is my tendency when I journey through something that shakes me up and requires a deepening of my emotional and spiritual growth, I turned to books for comfort and a way forward. At first I tried to maintain my commitment to marginalized voices, but the effort required felt like one more stressor, so I let myself off the hook. Instead, I read about body healing, generational trauma, and spirituality from some of the prominent writers in those fields – all of them from the dominant culture.

This healing period in my year is worth mentioning for a few important reasons.

1.) It highlights the lack of marginalized voices in books related to trauma/therapy/spirituality/body wisdom/etc. This begs the question: Where do people who aren’t from the dominant culture turn to find voices like them speaking to the deep healing work that they need to do? If you’ve experienced oppression, it’s very difficult to find healing from among the people who represent your oppressors.

2.) To stay on the quest for a deepening understanding of injustice, racism, etc., and to be able to continue to examine my own place within the systems that oppress people, I needed to turn inward for awhile to find my own strength and resilience. A deepening understanding of trauma, for example, helped me to heal some of my own so that I am more equipped to hold space for others who’ve faced trauma. I can enter into other people’s stories better when I have healed my own.

3.) My ability to find the voices that speak to my experience and help me heal is part of my privilege. I didn’t have to look very hard to find a therapist who looks like me and has enough education and training to support me and I didn’t have to look very hard to find suitable books that helped me understand my life experiences. My voice is well-represented and healing is relatively easy to find.

After a few months, I renewed my original commitment. I found I wasn’t quite ready for the heaviness of some of my earlier reading, so I looked for lighter reading. Comedic marginalized voices provided a nice balance and, in a surprising way, helped to normalize “the other” even more. When you’ve entered into the humour of a lived experience that is different from yours, you realize the threads that bind us together and give us common humanity. In a book on growing up Muslim in Canada, for example, I found myself chuckling at how similar some of the experiences were to my own Mennonite upbringing. Just as I felt like an outsider in my small town for the things I couldn’t do as a child (no dancing, drinking, attending community bingo nights, etc.), a young Muslim girl feels set apart for living a more restricted life.

By the end of 2016, I wasn’t ready to quit reading books by marginalized voice. Having worked through the earlier challenges of finding books that interested me, I now have a stack of books waiting for me and a long wish list of ones I want to get to eventually.

I have learned more than I can say from the reading I’ve done so far and I know I have much more to learn. At the beginning, I was learning about what it means to be Indigenous, black, brown, disabled, LGBTQ+, non-gender-binary, etc., but at some point I realized I was learning something that was equally important. By witnessing, if only for a fleeting moment, the world through their eyes, I was learning more about what it means to be a white, able-bodied, heterosexual, cis-gender woman and what privilege comes from those pieces of my identity.

When you’re a member of the dominant paradigm, you rarely have to look back at yourself in any kind of intentional self-reflection. The world is set up to support you, to centre you, to make you safe, and to make you feel normal, so you don’t have to work very hard at figuring it all out and there’s no need to challenge it.

I have the privilege of navigating the world with a kind of obliviousness in ways that others don’t, and my reading this year helped me see that more clearly. Since reading all of those books, I am more aware of, for example, how safe a bathroom might feel for a transgender person, or how accessible a space might be for a disabled person. I am also more aware of how little I’ve had to pay attention to either of those issues, and, more importantly, how I have contributed to the challenges marginalized people face and how I represent that which is unsafe for them.

Two terms came into my consciousness this year and both were made more clear by the reading I did – kyriachy and intersectionality.

From Wikipedia:

Kyriarchy, pronounced /ˈkaɪriɑːrki/, is a social system or set of connecting social systems built around domination, oppression, and submission. The word was coined by Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza in 1992 to describe her theory of interconnected, interacting, and self-extending systems of domination and submission, in which a single individual might be oppressed in some relationships and privileged in others. It is an intersectional extension of the idea of patriarchy beyond gender. Kyriarchy encompasses sexism, racism, homophobia, classism, economic injustice, colonialism, militarism, ethnocentrism, anthropocentrism, and other forms of dominating hierarchies in which the subordination of one person or group to another is internalized and institutionalized.

Intersectionality (or intersectional theory) is a term first coined in 1989 by American civil rights advocate and leading scholar of critical race theory, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw. It is the study of what Crenshaw contends are overlapping or intersecting social identities and related systems of oppression, domination, or discrimination. Intersectionality is the idea that multiple identities intersect to create a whole that is different from the component identities. These identities that can intersect include gender, race, social class, ethnicity, nationality, sexual orientation, religion, age, mental disability, physical disability, mental illness, and physical illness as well as other forms of identity. These aspects of identity are not “unitary, mutually exclusive entities, but rather…reciprocally constructing phenomena.” The theory proposes that we think of each element or trait of a person as inextricably linked with all of the other elements in order to fully understand one’s identity.

The broad range of my reading has contributed to my understanding of what it means to be intersectional AND someone who benefits from the kyriarchy. My life is impacted not just by one aspect of who I am, but by the intersection of multiple identities. I am never “just a woman” or “just a white person”. I stand at the intersection of those identities, just as every other person stands at their own intersection. My intersection means that I am both oppressor and oppressed, both settler and sexually colonized. Their intersection means something entirely different, and I can’t presume to understand it until I ask and until I sit and listen to their stories. Embracing their stories means embracing complexity.

Individually and collectively, we need to examine our wounds, our trauma, our privilege, our oppression, our marginalization, our power, and our guilt. As we do so, we need to be conscious of how our intersectional identities might impact other people.

I started out trying to diversify my bookshelf, but what I learned instead was that I needed to work on decolonizing my bookshelf and, consequently, my life. Diversity would only get me part way there. It might give me a collection of stories and ideas about what it was like to be marginalized. But a diversity lens still allows me to centre myself and my story and do little to challenge my privilege. Decolonizing is different – it invites me to examine myself and my place in the kyriarchy, deconstruct my own narrative of domination, and challenge that which allows me to live with privilege while others can’t.

I don’t want to make it sound like it was all drudgery and hard work, though. It wasn’t. Many of the lessons of this year were beautiful ones. Adding all of these voices to my life was like adding colour to a monochrome kaleidoscope – it added depth, beauty and texture to my view of the world and allowed me to see what I’d been missing. I found common threads in the stories that made me feel more connected to the humanity of all of the people I encountered.

Though I started the year feeling like it was my duty, as a white person, to challenge myself and stretch my worldview, I can now say that it is also my pleasure and privilege. I have fallen in love with these voices and I want more and more of their stories and their wisdom. They have challenged me and they have blessed me. They have pushed me past my own fragility and helped me listen more intently to what I couldn’t hear before. My life is richer for what they continue to bring to my world.

I still have much to learn and many teachers to teach me. For now, I will continue to centre those voices that are not centred on the bookstore shelves, because it is only in doing so that I can see myself and the world more clearly.

Though I wasn’t vigilant in keeping track of the books I read this year, here are the ones I remember and recommend (in no particular order:

- The Golden Son, novel Shilpi Somaya Gowda

- Calling Down the Sky, poetry by Rosanna Deerchild

- Birdie, novel by Tracey Lindberg

- Americanah, novel by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

- Celia’s Song, novel by Lee Maracle

- Gender Failure, memoir by Rae Spoon & Ivan E. Coyote

- Unbowed, memoir by Wangari Maathai

- Where the Peacocks Sing, memoir by Alison Singh Gee

- All About Love, non-fiction by bell hooks

- Bad Feminist, essays by Roxane Gay

- Laughing All the Way to the Mosque, humour/memoir by Zarqa Nawaz

- The Reason You Walk, Wab Kinew

- Half of a Yellow Sun, novel by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The books I read for healing/growth (not from marginalized voices)

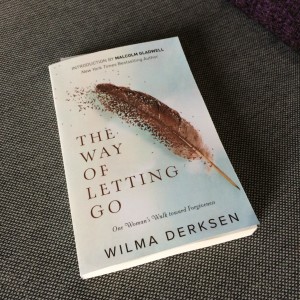

This week, I’ve been reading Wilma Derksen’s new book, The Way of Letting Go, about her thirty-two year journey to forgiveness after her thirteen-year-old daughter’s murder. The term forgive, she says, derives from ‘to give’ or ‘to grant,’ as in ‘to give up.’ Forgiveness is the process of letting go. It “isn’t a miracle drug to mend all broken relationships but a process that demands patience, creativity, and faith.”

This week, I’ve been reading Wilma Derksen’s new book, The Way of Letting Go, about her thirty-two year journey to forgiveness after her thirteen-year-old daughter’s murder. The term forgive, she says, derives from ‘to give’ or ‘to grant,’ as in ‘to give up.’ Forgiveness is the process of letting go. It “isn’t a miracle drug to mend all broken relationships but a process that demands patience, creativity, and faith.”