This is my friend Rosanna. She is fierce and funny and a little bit wild. She is also really, really smart, and has amazing skills as a poet and radio broadcaster. She has a national radio program and I get giddy every time I hear her voice on the radio, because she’s so good and because it makes my petty little ego feel puffed up to be friends with such a smart person.

This was us on Friday night at King’s Head Pub. We were being a little bit silly and a little bit fierce and our friend Angela snapped the picture mid-gangsta-hands-motion.

Rosanna and I are both moms raising fierce daughters. And we’re both writers and career women. And we’re both fiercely committed to social justice. And we both live in the same city and were both raised in rural parts of the same province. And we both like to get a little silly on a Friday night over wine.

But there’s one big difference between Rosanna and me. She is Indigenous and I am White. Her ancestors were the original inhabitants of this country and mine were the settlers. Hers were the colonized and mine were the colonizers.

Rosanna and I met last year when her face on the cover of a national magazine made her the unwilling poster child for racism in our city. Our city had been called the most racist city in Canada and both of us felt the need to do something about that.

When I read the article, I felt heartsick about it and determined to make a contribution to change in our the city, but didn’t know how to respond. I wanted to use my skills as a facilitator to gather people for conversations, but I didn’t want to do that alone. I didn’t want to be one of those “great white hope” leaders who takes the spotlight away from the people who deserve it. I wanted to do it in partnership with an Indigenous person, and so I waited for the right person.

Rosanna turned out to be the right person. When Rosanna posted on Facebook that she wanted to gather people around the dinner table for conversations, a mutual friend connected us, a few other people stepped in, and suddenly we had an event planned. We hosted over 90 people for a good meal and even better conversation. And then we did it again.

In the process, I learned a lot about what it means to be an ally. I made some mistakes, and tripped on my own privilege a few times, but I stuck with it, believing it was the right thing to do. All the way through it, Rosanna was gracious and forgiving (and funny to boot) and never made me or any of the other fumbling white people feel shame over any misguided words or wrong-headed actions.

The little troupe of women who pulled the conversations together came to call ourselves the Justice Ladies League. We even had badges and we wore them at the bar while we plotted our next attack on injustice. We talked about serious stuff, but damn we had fun together.

Life got busy and suddenly months had passed since we’d held our last event or been silly over drinks together. When the one year anniversary of the magazine article rolled around, we remembered how much we liked each other, so we planned a spontaneous reunion of the Justice Ladies League at the King’s Head Pub.

That reunion was this past Friday night. I was late leaving the house, so I drove instead of taking the bus. That limited me to only one glass of wine, but that didn’t mean I wasn’t up for some fun.

At the end of the evening of catching up, laughing, and pretending we were bandits ready to wreak havoc on the city, four of us left the bar while Rosanna went to join a few other friends at another table.

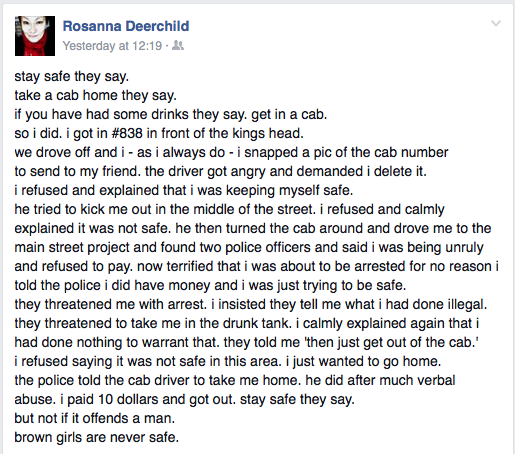

I drove home, safe and sound and thought not much more of it, until this morning when I checked Facebook and discovered… this is what happened to Rosanna on the way home from the bar…

Suddenly I felt that same sickening feeling I’d felt when I read the Maclean’s article. This is what happens when you’re an Indigenous woman in our city. This is the risk you take just trying to take a cab home on a Friday night.

There are over 1500 missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada. Even though she is smart and funny and a published poet and a national broadcaster, my friend Rosanna lives with the daily awareness that any day, she could become one of them.

That sickening feeling in my stomach was partly because I knew that this would not have happened to me. If I had taken a cab home and done the same thing Rosanna did, the cab driver would almost certainly have kept silent and driven me home. There’s no way I would have ended up at the Main Street Project and there’s no way police officers would have considered taking a cab driver’s side over mine or sending me home without protecting me from an abusive cab driver. Because I am white. Because I am privileged. Because I live in the predominantly white suburbs. Because he wouldn’t have assumed that the colour of my skin meant I was a drunken trouble-maker.

I need to go further with this story, because it’s important. After I saw Rosanna’s post, I felt guilty about not giving her a ride home. If only I’d stayed a little longer. Or if only I’d been in the cab with her.

I felt the sting of shame over my own white privilege. Why do I have the right to drive home safely or even take a cab without worrying that I might not make it home? Why has it never occurred to me to warn my daughters about cab drivers when they come home from the bar?

I shared Rosanna’s story on Facebook, and people responded with appropriate outrage, but then something else happened. Some of the people who responded were doing so because they felt badly for ME – because I’d worked hard to challenge racism and had to face something like this. “Keep up the good work, even though it’s discouraging.”

But the work wasn’t about ME. And the story wasn’t about ME. And if it was, then my ego was getting in the way.

I had a sudden memory of the article my friend Ericka shared awhile ago about white women’s tears. The article talks about how white women’s tears in response to stories of racism turns the spotlight onto themselves and makes people feel compassion for THEIR emotions rather than pointing their compassion in the direction it should go. By showing too much of their own emotions, well meaning white women co-opt the story.

I found the article challenging at the time, because I’ve always encouraged authentic emotions and wouldn’t want to tell a white woman to stop if she was feeling genuinely heartbroken over the story of someone’s black son being murdered. I knew, for example, that I had shed tears at the vigil for Tina Fontaine (a young Indigenous woman whose body was found in the river), and that didn’t feel wrong.

But now, as I found myself wanting to share my emotions over the bullying Rosanna had received at the hands of the cab driver and police officers, and my own guilt for not driving her home, I was doing the very thing the article warned against. I was co-opting Rosanna’s story and inviting people to feel empathy for me instead.

No, I didn’t mean to do that. I only meant to support my friend. But sometimes it’s the well-meaning things we do that cause the most damage.

Ugh. This ally stuff is challenging!

What if I just deleted my post and didn’t share anything? I could pretend I hadn’t seen Rosanna’s post and go on with my nice easy life. Who would be the wiser? That way I wouldn’t risk any blunders and I wouldn’t need to expose my white privilege.

But Rosanna is my friend! How could I ignore what happened to her on an evening when I’d been with her? I couldn’t and it really wasn’t a temptation at all.

The only thing I could do was to put my discomfort on the line, risk making a few blunders (and admit them), and honour this friendship that matters to me. Because the risks I take in speaking out and challenging people are insignificant in the light of the risks my Indigenous friends face every day.

So I said this on Facebook… “I appreciate all of your words AND I want to say that I didn’t share this because ‘poor me – I work so hard and nothing changes’. If I make the story about me, that brings it all back to my own white privilege. This is about the reality of what Indigenous women have to live with every day. I bow gracefully out and make the story theirs.”

The truth is, I may lose followers out of this, and I may get some backlash, because it happens every time I write about racism, privilege, feminism, etc. – especially when I admit my own blunders. But again, the fact that I can even consider staying silent is a mark of my privilege.

(As you can imagine, I’m also struggling with the irony of saying I don’t want to make the story about me and then writing a whole blog post about it.)

But I have a platform and I have a voice, and silence doesn’t feel like an option. Silence doesn’t feel like true friendship. And Rosanna is worth a whole lot more than that.

So please, if you learn anything from this story, don’t make it about me. Don’t pat me on the back for telling the story, because I did nothing courageous. I don’t need the ego strokes or the reinforcement of my privilege. Instead, use Rosanna’s story to galvanize you to look into your own heart, challenge the racism you see around you and in you, and find a way to be an ally for the marginalized members of your own community.

And, if you want to know truly courageous truth-telling, read the poetry book Rosanna wrote with her mom, about her mom’s residential school experience. And read other stories that challenge you. And talk to the people who are facing this kind of struggle every damn day. And ask them how you can be an ally and stand with them against injustice.

Do it for Rosanna and do it for her daughters and do it for Tina Fontaine. And do it for my daughters and your daughters and our city and everyone who feels unsafe because they are not part of the dominant culture.

Because if we don’t challenge the racism, wrestle with our own privilege, and listen to the stories of the marginalized, then nothing will ever change.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my weekly reflections.