When I was a young teenager, our family arrived at our tiny rural church for a special evening service to find a sign on the door. “It is illegal to gather here,” was the essence of the message. “Those who worship here will be tried for heresy and sentenced to death.”

A church member greeted us at the door and whispered something to us about a secret meeting place in the basement of a nearby church member’s home. With a little excitement and perhaps a little fear, we made our way to the alternative meeting space.

We weren’t really in danger. This was a re-enactment of the early days of the Mennonite faith in Europe, meant to give us a sense of what it was like when our ancestors were tortured and killed for their beliefs and for their defiance against the all-powerful Catholic Church.

There’s a deep thread of martyrdom in the Mennonite narrative. We grew up on stories of how courageous the early believers were, how many of them died and/or were tortured for their faith, and how we, too, should aspire to have such strong faith. Those things our forebears died for (adult baptism, pacifism, a flattened church heirarchy, and a belief that the water and wine of communion wasn’t literally transformed into the body and blood of Christ) became the most salient parts of our identity. A good Mennonite was one who clung to these beliefs on punishment of death.

So deeply runs the narrative of martyrdom that the second most popular book in Mennonite homes (after the Bible) is Martyrs Mirror, a dense book of more than 1500 pages full of the horror stories of our lineage. The full title of the book is The Bloody Theater or Martyrs Mirror of the Defenseless Christians who baptized only upon confession of faith, and who suffered and died for the testimony of Jesus, their Saviour, from the time of Christ to the year A.D. 1660. (The word “defenseless” refers to the Anabaptist belief in non-resistance.)

My dad’s copy of Martyrs Mirror is on my bookshelf, though I’ll admit to an uneasy relationship with it.

I left the Mennonite church behind in my mid-twenties. Not only was I dating a Catholic, but I was having serious doubts about how much I could align myself with a Mennonite worldview and faith perspective. It wasn’t so much the early tenets of the faith that concerned me – it was the lifestyle restrictions it imposed (no drinking, card-playing etc.), the way it it seemed to sever my head from my body (by teaching that the body was the greatest portal through which sin entered, that dancing was wrong, etc.), and the belief that we had the true way to God and that others (even those who believed in the same God as we did) were headed toward damnation.

I didn’t abandon faith entirely, but I sought a different version of God/dess – one that was less masculine, less exclusive about who had access, less restrictive, and more accessible to my LGBTQ+ friends. I also needed a faith that wasn’t so ruled by the fear of hell that we had to jeopardize relationships in order to save people’s souls.

It seemed backwards to me, this faith, and so I tucked it away and didn’t mention it often. There was some shame involved, I suppose, in the assumptions people automatically jumped to when I mentioned my Mennonite background. I could see in their eyes that their mental pictures of my childhood were that I’d been isolated in a Hutterite colony or that my family went to church in an Amish horse and buggy. None of those pictures were true for my background (we were of the variety of Mennonites that blended in and lived essentially the same as our neighbours, except for the no drinking/dancing/television part), but I got tired of having to explain the difference.

I left it behind and gave little thought to that part of my identity. I built a life around who I wanted to be in the world and largely ignored the part about how my lineage had shaped me.

It’s tricky to leave it behind entirely, though, because “Mennonite” is much more than just a religion. It’s a cultural identity, and, in some ways, an ethnicity. It’s the food we eat, the cultural practices we share, and the language we speak (ie. Low German, or “Plattdeutsch” – a derivative of German, Dutch, and English).

We’ve become a cultural group largely because our tormented history drew us together and turned us into nomads, moving from country to country in search of a place where we could live out our peace-loving, adult baptizing beliefs without fear of death. From Holland, Germany, and Switzerland, many Mennonites moved to the Ukraine and Poland (formerly part of Russia) when they were promised safety. But when the revolution rose up in Russia, they were tortured again and most left for North and South America. The nomadic nature of our past deepened the roots of tribalism and strengthened the cultural identity of what it meant to be Mennonite.

Whenever people ask about what nationality I am or where my family originated (as every settler in Canada is asked – because we all came from somewhere), I don’t know how to answer. Depending on who asks, I say some version of “I’m Mennonite, but I’m not sure what nationality I am. Likely a combination of Dutch and German, though we came to Canada via Russia.” Other than that, my roots were blurry.

Severed from my own sense of identity and rootedness, I became strangely fascinated with everyone else’s. I collected artifacts from the countries I traveled to, I visited other gatherings of faith and spirituality, and I practiced rituals that intrigued me. In a sense, I lived out the nomadic part of my heritage, wandering around and experiencing cultures and countries that were not my own.

Gradually, though, I became aware of a longing in myself that I hadn’t recognized before. I longed for a sense of belonging, a sense of my own indigeneity, a sense of place. I looked wistfully at those who had a strong sense of their lineage, and I wondered what that must be like. I attended cultural events and marvelled at the pride people had in the people and places they came from.

This longing showed up in my work too. As I deepened my understanding of what it means to hold space, I realized that there were other reasons why it was worthwhile to pursue a better understanding of who I was and where I was rooted.

First, I became more and more familiar with how trauma is rooted not only in one’s body but in one’s lineage. I learned about generational trauma and held space for friends and clients as they uncovered the trauma they’d inherited from parents who were residential school survivors or holocaust survivors. As I did so, I became increasingly curious about how centuries of trauma in the Mennonite people, as they ran from country to country to stay alive, might still be in our DNA as well. And I also wondered how that trauma had resulted in the strength, resilience, and resourcefulness that is part of what it means to be Mennonite.

Second, I became increasingly aware of how people who are not well rooted in their own indigeneity and spirituality, and do not have a strong sense of their relationship with the earth will culturally appropriate the rituals, artifacts, and spiritual practices of other people and will use spiritual bypassing to defend their actions. I saw signs of that in my own intrigue with other cultures and spirituality.

Third, I wondered how my lineage had shaped me and how it might be threaded into my work on holding space. I contemplated, for example, that my ability to sit with a person walking through the darkest shadows or expressing the deepest pain without looking away might be related to the courage of my ancestors as they faced the gallows or the fire. I also wondered whether a history of being “the other”, both in my personal history and the history of my lineage, might have contributed to the fact that I have a surprisingly large percentage of close friends who are from marginalized groups (Indigenous, Black, People of Colour, Muslim, LGBTQ+, etc.).

With all of those reasons for deeper inquiry, I started a quest, a few months ago, to find out more about my roots. Then, as though the universe were encouraging me to step onto this quest, I was offered two opportunities in the coming year to travel to Holland, where my ancestors likely originated. It also seems like no accident that the people I’ll be working with there are experts in family systems constellations, who understand how family stories are threaded through our lives.

My quest started in earnest when I dug up a few of my Dad’s books – a Plett history book (which tells the story of my family since our arrival in Canada in 1875) and Martyrs Mirror. Then I joined ancestry.ca, ordered a DNA kit and stayed up almost all night tracking my family tree as far back as I could (to the early 1600s). I learned that one of my great-great grandfathers had abandoned the Mennonite church, moved away from the Ukraine and married a non-Mennonite wife. I also learned that there’s a likelihood that I have some British roots along with my Dutch/German roots.

I became most hungry for the stories of the women in my lineage, though. Who were they? Had they been as strongly committed to their faith as their husbands and fathers, or had they learned submission at an early age and simply went along with what they’d been taught? Had they suffered at the hands of the torturers as well, or had they been left behind to care for the children and live through the trauma? The Plett history book gave little clues, so I turned to Martyrs Mirror.

Though the stories of male martyrs far outnumber the stories of women, I was surprised to find quite a few women accounted for. Not only were they equally courageous and defiant, but they were articulate and well educated. Included in the book is more than one letter penned by women in prison, written to encourage their families and/or fellow believers not to waver in their faith even if they were put to death. And there are several accounts of the last defiant words spoken by women before they were slaughtered – always refusing to denounce their faith or give up the names of others in their communities.

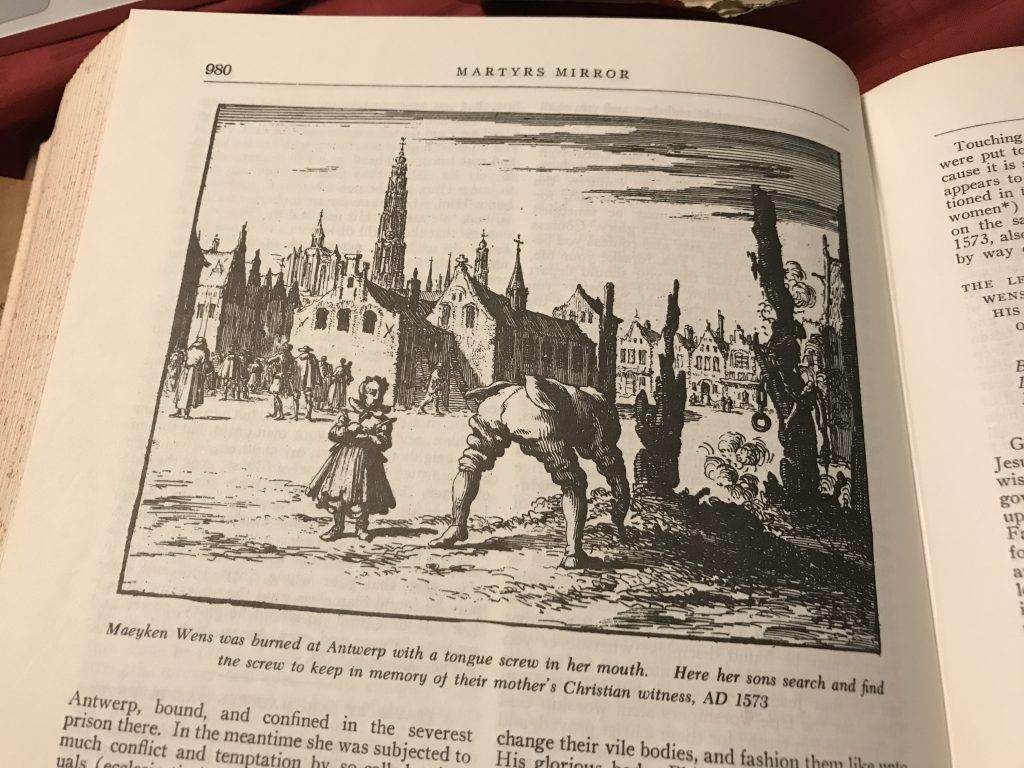

A number of times, while flipping through the pages, looking for names of women, I found myself in tears. There was the woman whose mouth was stuffed with gunpowder before she was tossed into the flames, the two sisters who were drowned together, and the woman who refused to recant even after screws were applied to her thumbs, fingers, and hips. And then there was the woman who was pregnant when first apprehended and who was allowed to go home until the baby was born. “She did not flee, but boldly remained,” and when they came back for her, after the baby was born, she surrendered and was executed by the sword.

The one that brought the most tears, though, was Maeyken Wens, of the city of Antwerp, who was burned with a tongue screw in her mouth. Her fifteen-year-old son Adriean “could not stay away from the place of execution on the day on which his dear mother was offered up; hence he took his youngest little brother, named Hans (or Jan) Mattheus Wens, who was about three years old, upon his arm and went and stood with him somewhere upon a bench, not far from the stakes erected, to behold his mother’s death.” When they brought her out, though, Adriean lost consciousness and didn’t wake up until his mother was dead. Afterwards, he “hunted in the ashes, in which he found the screw with which her tongue had been screwed fast, which he kept in remembrance of her.”

I don’t know whether any of these women are in my direct lineage, but I know that they’re in my tribal lineage, and so I claim them as my ancestors. Their courage, as well as their trauma, has been passed down through the centuries and now resides in my body.

What I take from their stories is a strong sense of a moral compass, a willingness to stand against the authorities, and a belief that they answered to a higher authority than the government or the church that was sanctioned by the government. Theirs was the social justice struggle of the day, challenging the version of patriarchy and supremacy that existed in their time.

What does all of this mean for me? I don’t entirely know. I know that I will continue this quest for a deeper understanding. I know that when I am Holland this coming year, I will try to visit the land on which my lineage was once rooted. I know that I will do my best to live in a way that honours the courage and the stories that have been passed down through me. I know that I will continue to explore what parts of my faith history still matter to me and what parts need to be released. I know that I will inquire more deeply into the way that my head has been disconnected from my body as a result of the trauma and the religious beliefs.

A few weeks ago, the term “conscientious disruptor” landed in my journal when I was writing about how I often feel a strong sense of calling to “speak truth to power” when I witness oppression and injustice. The moment I saw it written down I realized that it wasn’t a unique thought – instead it was a reflection of the lineage I carry. My Mennonite people have always been “conscientious objectors”, standing up for pacifism and refusing to join the military even when they were persecuted or banished from the country because of it.

The mantel of “conscientious disruptor” does not sit lightly on my shoulders. It’s a bold and dangerous thing to be. But I know that the courage of my ancestors lives in me and I will do my best to serve our lineage well.