by Heather Plett | Mar 16, 2017 | Community, Compassion, connection

Melancholy: a feeling of pensive sadness, typically with no obvious cause

That sounds about right for my state of mind this past week. I hesitate to call it depression, because it doesn’t feel that heavy, but there is definitely “pensive sadness” going on and it has no obvious cause.

When this familiar sense of melancholy comes at this time of year, I usually chalk it up to the end of winter, when I’m a little more sluggish from not taking as many long walks in the woods and not getting as much sunshine as I need. I get a little imbalanced when I lose my connection to the natural world. I’m pretty sure that it will pass soon (Spring always revives me), but for now, my creativity is low, my resilience isn’t what it normally is, my emotions are a little tender, and I feel disconnected. I stare at blank pages when I should be writing, I crawl into bed earlier than usual, I cry unexpectedly, and I watch too much Netflix.

A couple of things happened last week that were quite minor, but because of my state of mind, I took them more personally than I normally would. Though none of the people involved meant any harm, my tenderness left me feeling a little lonely and a little rejected. There was no true rejection involved (I still feel well loved by them), but in the middle of my fragility, it’s always easier to make up stories that align with how I’m experiencing the world. Feelings of disconnection often lead to greater disconnection.

Not long ago, I was on the other side of that story, inadvertently wounding someone who was going through her own state of tenderness. Unaware of her emotional state, I said something that normally would have been received with ease, but instead carried some wounding.

“At two, you’re at abstraction.” That’s a line from a Sara Groves song (that I think she borrowed from someone else, but I can’t find the source) that points to the impossibility of fully understanding another person’s reality. Another person’s pain, joy, love, trauma, history – they’re all just abstract concepts for us because we have never lived inside of them. We can never really “walk a mile in another person’s shoes”.

Despite our best efforts to be compassionate and understanding, our well-meaning words can land the wrong way and leave a person feeling wounded, lonely, misunderstood, defensive, angry, etc. That’s one of the reasons why, in our efforts to hold space for other people, we need to avoid falling into the trap of taking responsibility for their emotional response to our words or actions. Each of us is a sovereign individual with our own stories, our own interpretations, and our own emotions and when we take too much responsibility for another person, we diminish their sovereignty.

At a workshop a few weeks ago, Dr. Gabor Maté talked about how trauma can shape a person’s world and change the way they respond to stimuli. When a person grew up with trauma (either in the form of a traumatic event, or as a result of being raised by caregivers with unresolved trauma) their fight/flight/freeze instincts are heightened and they are inclined to over-react to stimuli that brings them back to their traumatic memories. Unresolved trauma, he said, makes it impossible for us to be in the present moment. “When we’re triggered, the emotions that show up are those of the abandoned child. We don’t react to what happened – we react to our interpretation of what happened based in our traumatic memory.”

Even compassionate people can inadvertently trigger someone’s trauma. Think about the last time you said something to another person that you thought was fairly innocuous and they reacted with defensiveness or anger that seemed out of proportion for the moment. There’s a good chance that there was something in what you said that triggered an old wound that they may not even know they still have. In that instant, that person was not the mature adult you thought you were talking to – they were a scared child relying on an instinctual response for their own protection. While they may need your empathy in that moment, and you might make a mental note to adjust your behaviour in the future to avoid triggering them further, you can’t take their autonomy away by trying to fix their problem for them.

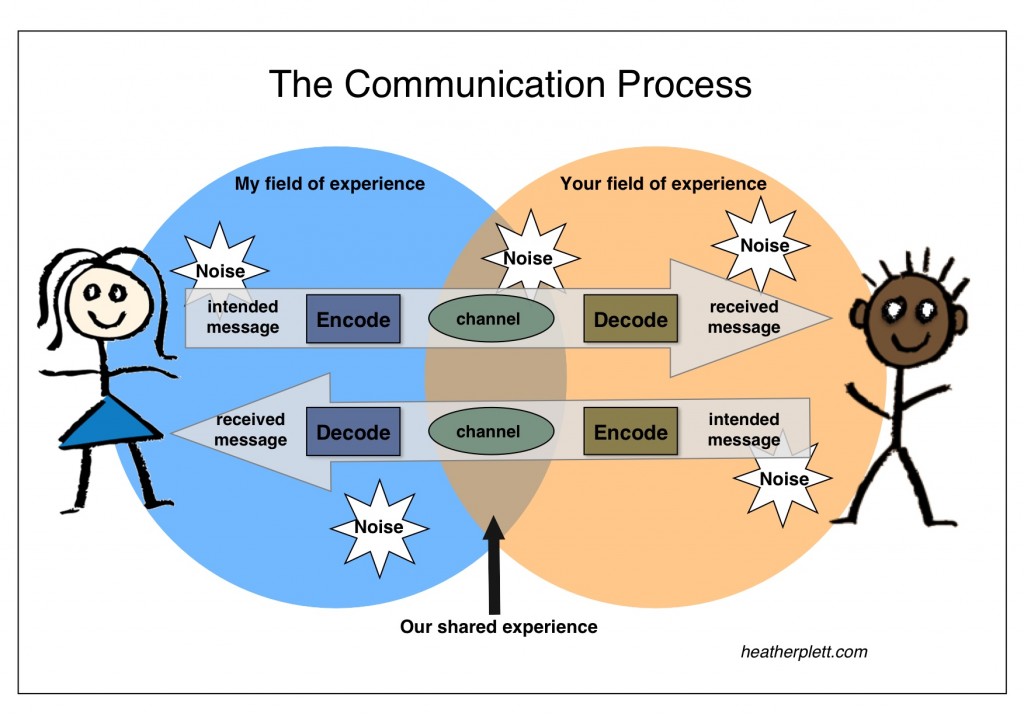

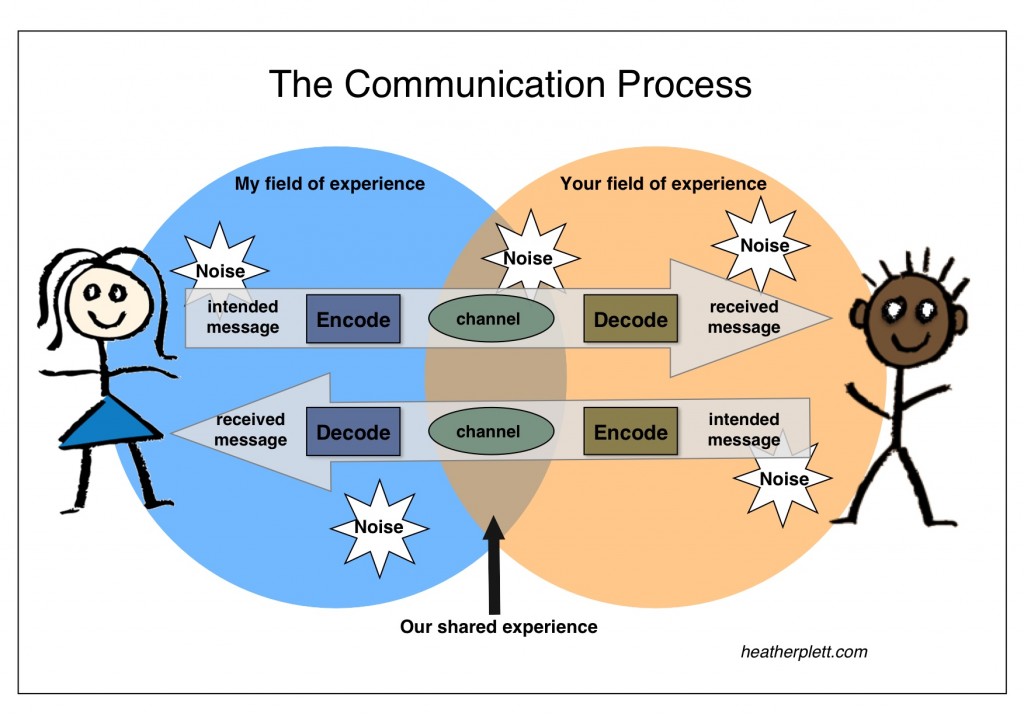

When I used to teach a university-level course in communication, I would always start with the following diagram to help my students understand that, in every communication, there are complexities and potential pitfalls that we can’t fully anticipate or mitigate.

(Note: this is my version of a popular model used in communication training, but I don’t know the original source.)

Each of us lives within a unique field of experience that may overlap with other people’s experience, but is never exactly the same. When I want to communicate with you, my intended message is shaped and encoded by my field of experience, which includes factors such as my gender, race, culture, disabilities, lived experiences, language ability, emotional state, etc.

I choose the channel of communication to best offer the message (ie. will I make a phone call, wait until I can talk to you in person, or send an email?). If I am compassionate, I will consider your field of experience when choosing the channel (ie. if you are hearing impaired, a phone call might not be the best method), but I’m limited in how much I can understand your reality so I may make mistakes. On top of that, no matter how carefully I encode the message and how intentional I am about the channel of communication, there is always unexpected noise that can disrupt or distract us at any moment in the process (ie. a child needing attention in the middle of a personal phone call, a disturbing story on the news, a misunderstanding, etc.).

The message crosses over to you and is, in turn, shaped and decoded by your own field of experience and your current circumstance. As I mentioned above, for example, you might be going through a period of tenderness that I had no way of knowing about when I initiated the communication. Even the most well-intentioned communication can go astray, and by the time you’ve decoded it, it may have a very different shape than what I intended. Much of our encoding and decoding processes happen in mere seconds during the course of a conversation, so we aren’t aware of all of what has shaped and reshaped what’s passed between us.

If you choose to engage in two-way communication, you send your own message across the reverse path, back through our fields of experience, risking similar misinterpretation, triggering, etc.

Given the potential complexity of even the simplest conversation, and given the fact that only a small portion of the process is within our control or within our conscious understanding, what can we do to improve the process? How can we be better communicators who wound others less often and receive fewer messages as wounds?

When you are the sender of the message:

• Pay attention to how your message is being shaped by your field of experience.

• Be humble, recognizing the limitation of your understanding of the other person’s field of experience.

• Especially where the differences are vast and there may be power imbalances, do your best to learn about the other person’s field of experience instead of passing judgement (especially if you are the one who holds more power).

• Be aware of the other person’s emotional response and check in when something doesn’t seem to land well, but don’t judge or try to control the emotion.

• Take responsibility for what you’ve said and allow the other person to take responsibility for their response.

• Allow for processing time in the conversation. Pauses may help to alleviate misunderstanding.

When you are the receiver of the message:

• Recognize the limitations that are at play in the sender’s lack of understanding of your field of experience.

• If you trust that the person will honour your current state of mind (ie. if there’s grief, depression, etc. going on), let them know that you may be limited in your capacity to receive.

• If you have a strong emotional response to the message, pause for a moment to check in with yourself. Recognize that the first reaction may be your instinctual desire to protect yourself and may not be fully based in the current situation.

• Hold the other person accountable for their words (especially in the case of harsh or oppressive language) and recognize when it may be in your best interest to stand up for yourself and/or walk away.

• If there is a misunderstanding and the relationship is important to you, reflect back to the person what your interpretation of the message is, based on your field of experience, and offer them an opportunity to reframe it.

• Take the time you need before sending a message back.

• Remember that you have a right to set boundaries and protect yourself.

Each situation is different, and based on how valuable the relationship with the other person is, you may or may not want to invest in the effort it takes to work through misunderstanding. If, for example, you’ve been verbally assaulted by a stranger at a bus stop, you probably won’t have any interest in figuring out how to communicate across your differing fields of experience. If, on the other hand, you love and trust the other person and believe that the relationship will be strengthened by deeper understanding, you’ll want to invest more time and energy in cutting through the noise.

*****

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my bi-weekly reflections.

by Heather Plett | Feb 15, 2017 | circle, holding space

My three daughters are all very different in how they view the world, how they communicate and how they process emotions. One of the most challenging things I’ve had to learn as their mom is that I have to listen to them differently.

One is introverted and takes a long time to process things, so even when I sense that something might be bothering her, I often have to wait a couple of weeks before I’ll hear about it. One is more extroverted and tends to think and experience the world the most like I do, so I often make the mistake of assuming I know things about her before I’ve taken the time to genuinely listen. A third is very private about her emotions and uses humour as one of her ways of processing the world, so I have to listen extra carefully for the subtle things she’s saying underneath the witticism.

I don’t always get it right. In fact, a lot of times I don’t. There are a surprising number of things that get in the way of good listening. Sometimes there are too many distractions, sometimes I’m tired, sometimes they’ve hurt my feelings and I’m resentful, and sometimes I just want them to be more like me so I don’t have to work so hard to figure them out.

Listening takes a lot of practice. Even though we develop our ability to hear while still in utero (unless we’re hearing impaired), genuine empathic listening is a skill that takes much longer to develop. And even when we’ve worked hard to develop it, we often mess it up.

Not only does listening take a lot of practice, it takes a lot of vigilance and intentionality to stay in it. Sometimes in a coaching session, for example, I’ll be in deep listening mode and suddenly something will distract me or trigger me and I’ll have to work really hard to stay present for the person in front of me. I can’t always identify what it was that pulled me away – it can be a body sensation (ie. my throat suddenly feeling like it’s closing, triggered by something they said), an emotional response (ie. my eyes fill with tears and suddenly I’m in my own story instead of theirs), or my own ego (ie. wanting to insert my own answer to their problem rather than wait for them to find their solution). Each time something like that happens, I have to bring my attention back to the person in front of me.

Over the weekend, I asked my Facebook friends a series of questions about listening.

1. What do you think are the best indicators that someone is genuinely listening to you?

2. What do you think are the indicators that someone is NOT genuinely listening to you?

3. When do you find it most challenging to listen to another person?

4. What personal work, self-care, etc. helps you be a better listener?

There were a lot of great answers to my questions. (Click on each question to see all of the responses.) Here’s a summary of some of the things that struck me in the answers:

- Genuine listening can’t be faked. While there were a lot of responses about outward signals that someone is listening (eye contact, bodily engagement, good questions), there wasn’t agreement about which signals were most valuable and there was lots of indication that people need to have a genuine felt sense that the person listening is fully present.

- Culture and context matter. Some cultures, for example, don’t value eye contact. And some contexts (ie. when the speaker has a lot of shame or trauma) require a more nuanced form of listening that may mean no eye contact and/or no questions.

- “Ultimately, a good listener allows the person they are listening to to hear THEMSELVES.” (Chris Zydel) When we, as listeners, interject too much of ourselves in the act of listening (questions, interruptions, too much body language, etc.) we can pull the person away from the depth and openheartedness of their own story.

- Genuine listening involves stilling your body and mind so that you can be fully present. In response to the question about indicators when someone is not listening, several people mentioned fidgeting, checking devices, not making eye contact, looking past the speaker, nodding too much, etc., indicating that when we are being listened to, we are usually perceptive to the body signals that a person is genuinely engaged with us.

- The behaviour of the person speaking strongly impacts our ability to listen to them. Approximately three quarters of the answers to the question about when people find it most challenging to listen to another person were about the speaker’s behaviour (when they are self-righteous, condescending, not willing to be openminded, basing their opinions on propaganda, performing rather than speaking from the heart, etc.) rather than the listeners. Fewer people identified their own blocks (when I am angry, weary, in disagreement, wrapped up in my own stuff, unwell, traumatized, etc.)

- Both speaker and listener have to be engaged and willing to be openhearted for it to work. Genuine listening is a two-way street and it can’t happen when one or the other is checked out, distracted or not being honest with themselves. If the speaker is closed off or defensive, it shuts down the ability to listen. If the listener is closed off, triggered, etc., it shuts down the speaker’s willingness to be vulnerable.

- Genuine listening requires self-awareness and good self-care. When we have done our own healing work, paid attention to our own triggers, and taken time to listen to ourselves first, we are in a much better position to listen to others.

Much of what I’ve learned about both listening and speaking, I’ve learned by practicing and teaching The Circle Way. The three practices of circle are: 1. To speak with intention: noting what has relevance to the conversation in the moment. 2. To listen with attention: respectful of the learning process for all members of the group. 3. To tend the well-being of the circle: remaining aware of the impact of our contributions.

Gathering in The Circle Way means that we slow conversation down and give more intentional space to both speaking and listening. When we use the talking piece, for example, there are no interruptions, cross-talk, etc. Nobody redirects what you’re saying by interjecting their own questions, nobody diminishes your wisdom by interjecting their answers to your problems, and everybody is trusted to own their own story and look after the circle by not taking up too much space or time. It can take a lot of practice (some people are quite resistant to talking piece council because they don’t feel it’s genuine conversation if no questions are allowed), but once you get used to the paradigm shift, it’s quite transformational.

According to Otto Schamer and Katrin Kaufer in “Leading from the Emerging Future”, there are four levels of listening.

- Downloading: the listener hears ideas and these merely reconfirm what the listener already knows.

- Factual listening: the listener tries to listen to the facts even if those facts contradict their own theories or ideas.

- Empathic listening: the listener is willing to see reality from the perspective of the other and sense the other’s circumstances.

- Generative listening: the listener forms a space of deep attention that allows an emerging future to ‘land’ or manifest.

Listening becomes increasingly more difficult as we move down these four levels, because each level invites us into a deeper level of risk, vulnerability and openness. There is no risk in downloading, because it doesn’t require that we change anything. Factual listening is a little more risky because it might require a change of opinion or belief. Empathic listening increases the risk because it requires that we open our hearts, engage our emotions, and risk being changed by another person’s perspective. Generative listening is the most risky of all, because it requires that we be willing to change everything – behaviour, opinions, lifestyle, beliefs, action, etc. in order to allow something new to emerge.

Generative listening not only requires a willingness to change, but a willingness to admit I might be wrong.

For example, when I engage in generative listening around race relations, I have to be willing to admit that I have benefited from the privilege of being white, and that I might be guilty of white fragility. If I am truly willing to listen in a way that generates an “emerging future”, there’s a very good chance I will be challenged in ways I’ve never been challenged before to accept the truth of who I am and how I’ve benefited from and been complicit or actively engaged in an oppressive system.

On a more personal level, generative listening as a mother means that I have to own my own mistakes and listen for the ways I may have wounded my daughters.

Not long ago, I was speaking with my oldest two daughters about some of the past conflict in our home, and I heard things that were hard to hear about how they felt betrayed by me when I didn’t protect them and didn’t help them maintain healthy boundaries. Everything in me wanted to defend myself and get them to understand my point of view, but I knew I would only do more damage if I did that. If I wanted our relationship to grow deeper and our home to feel more safe for all of us, I had to listen to their pain and not shut it down.

A few years ago, I wouldn’t have been nearly as receptive to my daughters’ words. Some of it, in fact, they tried to tell me then but I didn’t listen. Back then, I was still too wounded and didn’t have enough self-awareness to listen well. I would be much quicker to jump to my own defence or to offer a short-sighted solution.

Through the healing of my own wounds, I am much more able to hold space for theirs.

I’ve learned to listen better to my daughters, but there are still some spaces where I have a very difficult time engaging in generative listening. Some of the spaces I still have difficulty with are when I have to face too many of my own flaws, when the person speaking triggers unhealed trauma memories, or when the other person has more power or influence in a situation than I do. I will continue to heal and build resilience so that I am not shut down in these spaces. Some of that involves listening to myself more deeply and finding spaces where I am genuinely listened to.

This is not easy work, and it doesn’t happen by accident. Learning to listen is a lifelong journey that starts with the healing of the wounds that get in the way.

If you want to be a better listener, start by listening to yourself.

*****

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my bi-weekly reflections.

by Heather Plett | Jun 24, 2015 | art of hosting, circle

“The art of conversation is the art of hearing as well as of being heard.” ― William Hazlitt

The wedding I officiated on the weekend took place in a circle. The bride and groom and I stood in the centre, with the guests gathered around us.

After I had shared a few words of wisdom about marriage, I read a blessing and then passed a talking piece (a stone on which I’d printed their names) around the circle inviting each person to speak their own one-sentence blessing to the couple. If they didn’t feel comfortable speaking, they had the option to simply hold the stone for a moment and offer an unspoken blessing.

It was a beautiful and simple ritual that felt like the couple was being held in a giant container of love by their community.

As I said in this piece last November, the talking piece isn’t magic, but “what IS magic is the way that it invites us to listen in ways we don’t normally listen and speak in ways we don’t normally speak.”

When a talking piece goes around the circle, the person who holds it is invited to “speak with intention”. Everyone else is invited to “listen with attention” and not interrupt or ask questions. Everyone in the conversation is invited to “tend the well-being of the circle”. (Those are the three practices of The Circle Way.)

A talking piece conversation has a unique quality to it. There is more listening, less interrupting,  more pausing, and, almost always, more vulnerability than ordinary conversations. Yes, some people get nervous about the talking piece (because it puts them on the spot and feels like pressure to say something important), but when they get used to it, (and when they realize that anyone is welcome to pass the talking piece without speaking) almost everyone acknowledges that the talking piece brought something special into the space that they’ve rarely experienced before.

more pausing, and, almost always, more vulnerability than ordinary conversations. Yes, some people get nervous about the talking piece (because it puts them on the spot and feels like pressure to say something important), but when they get used to it, (and when they realize that anyone is welcome to pass the talking piece without speaking) almost everyone acknowledges that the talking piece brought something special into the space that they’ve rarely experienced before.

The talking piece is not meant for every conversation, but I believe it should play a more significant role in many of our conversations. Here’s why:

1. The talking piece invites us to listen much more than we talk. When in a circle with a dozen people, I have to listen twelve times as much as I talk. That’s a very good practice. Listening opens our hearts to other people’s stories. It invites our over-active minds and mouths to pause and be present for people who need to be witnessed. And when it’s our turn to talk, we know that we are being listened to just as intently.

2. The talking piece encourages us to get out of “fix-it” mode. When a friend shares a problem with us, it usually feels more comfortable to jump in with a solution than to sit and really listen. But unless that friend has asked for advice, what she/he probably needs more than anything is a listening ear. The talking piece doesn’t allow us to interrupt with our version of “the truth”. Often, simply because they’ve been heard in a deeper way than they’re used to, people walk away from the circle having figured out their OWN solutions for their problems.

3. The talking piece makes every voice equal. Nobody has the podium in a circle. Nobody stands on a stage. Each voice makes a valuable contribution to the conversation and none is more important than the others. With so many race issues happening recently (especially in the U.S. and Canada), I like to imagine what might happen if more people were to sit in circle with people of different races. What if we mandated interracial circle conversations for every high school student? What if students couldn’t graduate unless they’d spent time learning to listen to stories told by people who are different from them? What if Dylan Roof, for example, had sat in a weekly circle listening to stories from the black community? Might that have changed last week’s outcome?

4. The talking piece invites us more physically into the conversation. There’s something special about holding an object in your hand that has been passed there from hand to hand around the circle. It invites us to be present in not just our heads but in our bodies. It invites us to sink physically into the conversation, engaging in a deeper way because our hands are engaged along with our hearts.

5. The talking pieces creates the silence into which open hearts dare to speak. There’s a level of vulnerability that shows up in the circle that is rarely present in other conversations. Because the talking piece invites us to slow down and be more intentional, we don’t just talk about the weather or yesterday’s shopping trip. We talk about things that are real and we show up authentically for each other.

Have you had experience with a talking piece? I’d love to hear about it.

If you haven’t experienced it yet, don’t be afraid to try. Yes, you might get some funny looks from your family or friends when you pull out a stone, a stick, or even a pen and invite them to pass it around the circle, but there’s a very good chance – if they’re openhearted and authentic – that they will be surprised at what it brings to the conversation.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Feb 23, 2015 | art of hosting, Leadership

Ever since facilitating a conversation on race relations last week, I’ve been thinking about what it means to really listen. There were many challenges for me last week, and some of the greatest challenges were those that showed me how much deeper I need to take my own listening practice. Here’s what poured out of me this afternoon, after a few days of contemplating listening.

Listen, my heart said.

You don’t have to fix anything right now,

you just have to listen.

Listen to the wounded.

Listen to the joyful.

Listen to the fearful.

Listen to the warriors.

Listen to the poets.

Listen to them all.

Gather the bits of wisdom

they scatter on the ground

like seeds in the Spring.

Gather the bits of stories

they drop in your basket

like morsels for a picnic.

Gather it all

and let it change you,

let it reshape you.

Let it crawl under your skin

and plant itself there

like it was always part

of your own dna.

Listen to the elders,

to the children,

to the women,

to the men,

to the Spirit,

to the earth,

to yourself.

Listen for understanding

for compassion

for witness

for forgiveness

for healing

for growth.

Listen when they’re silent.

Listen when they’re loud.

Listen when they’re happy.

Listen when they’re sad.

Listen when they hurt you

in their efforts to hurt less.

Listen when they disagree with you.

Listen when you disagree with them.

Before you do anything else,

before you step onto the path,

before you become an agent for change,

before you know the answers,

before you try to lead anyone,

just listen.

Listen.

And then let your deep listening

be your guide

and let your courage lead you forward.

more pausing, and, almost always, more vulnerability than ordinary conversations. Yes, some people get nervous about the talking piece (because it puts them on the spot and feels like pressure to say something important), but when they get used to it, (and when they realize that anyone is welcome to pass the talking piece without speaking) almost everyone acknowledges that the talking piece brought something special into the space that they’ve rarely experienced before.

more pausing, and, almost always, more vulnerability than ordinary conversations. Yes, some people get nervous about the talking piece (because it puts them on the spot and feels like pressure to say something important), but when they get used to it, (and when they realize that anyone is welcome to pass the talking piece without speaking) almost everyone acknowledges that the talking piece brought something special into the space that they’ve rarely experienced before.