by Heather Plett | Aug 4, 2012 | change

I am a coach who loves to help people make a difference in the world.

Like the gymnastics coach at the Olympics who sits on the sidelines and bursts into wild applause when the gymnast excels sticks her landing, I love nothing more than to watch my clients shine in their giftedness. The world is a better place when we ALL share our gifts.

I’m exploring something new that will allow me to help more people do transformative work.

The challenge that I have is that often the people I most want to work with are people who live at the edges of the financial economy (usually by choice) and do not have a lot of money for the kind of coaching that would help them grow their world-changing work.

Here’s what I want to do… I want to transform my business model to free myself up to offer more gifts, and thereby free other people to offer their gifts as well. That doesn’t mean I will give away all of my services (I still need to make a sustainable income that will feed my family and keep a roof over our heads), but it means that I will accept and give gifts more freely to help more people serve as imaginal cells to transform the world.

Learn more about my new business model and the kinds of people I want to work with.

by Heather Plett | Aug 2, 2012 | Beauty

My daughters and I are home from vacation. We spent a few days camping in the woods (complete with our family’s traditional goofy conversations around the campfire that usually deteriorate into fart jokes), and then a few days doing more hedonistic things, like visiting the Mall of America and Valley Fair. (We try to satisfy everyone’s interests on our trips, and my teenage daughters are more inclined to shop than sleep in a tent in the woods.)

My daughters and I are home from vacation. We spent a few days camping in the woods (complete with our family’s traditional goofy conversations around the campfire that usually deteriorate into fart jokes), and then a few days doing more hedonistic things, like visiting the Mall of America and Valley Fair. (We try to satisfy everyone’s interests on our trips, and my teenage daughters are more inclined to shop than sleep in a tent in the woods.)

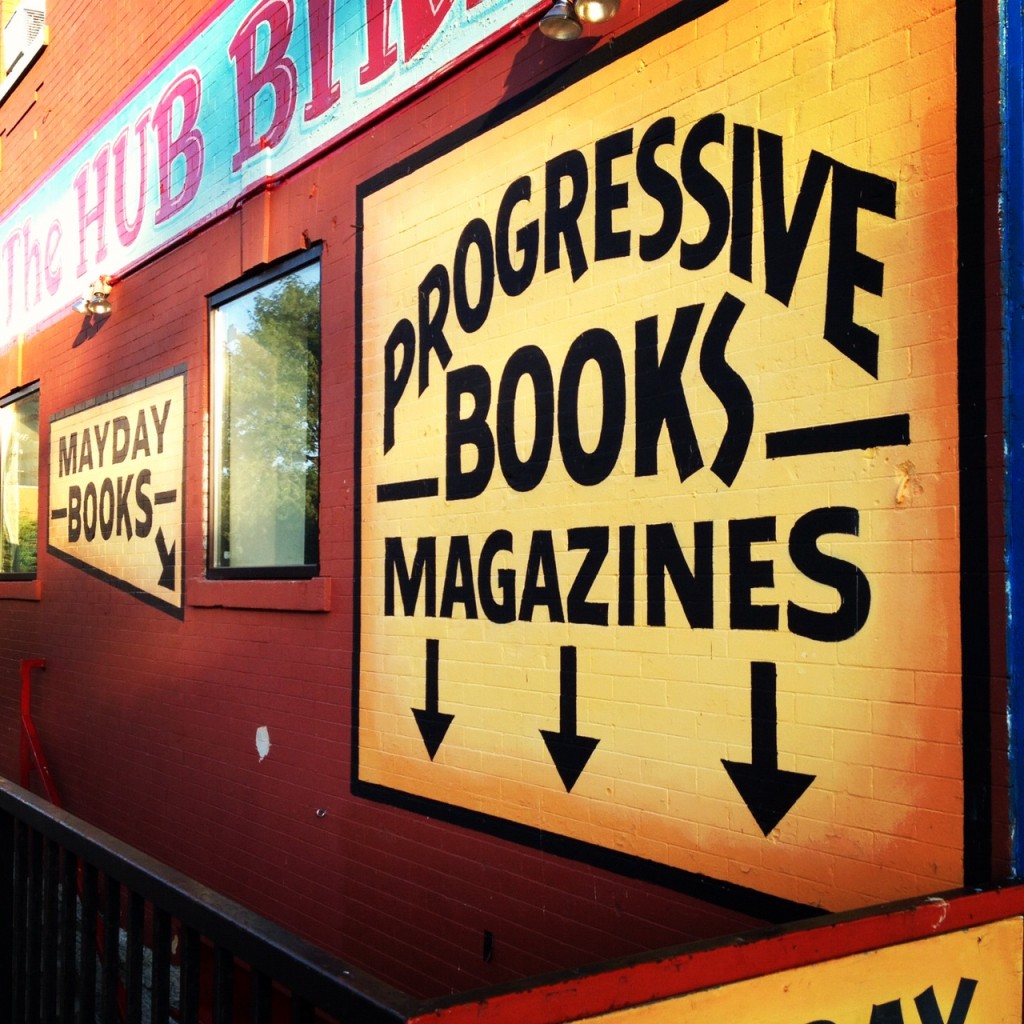

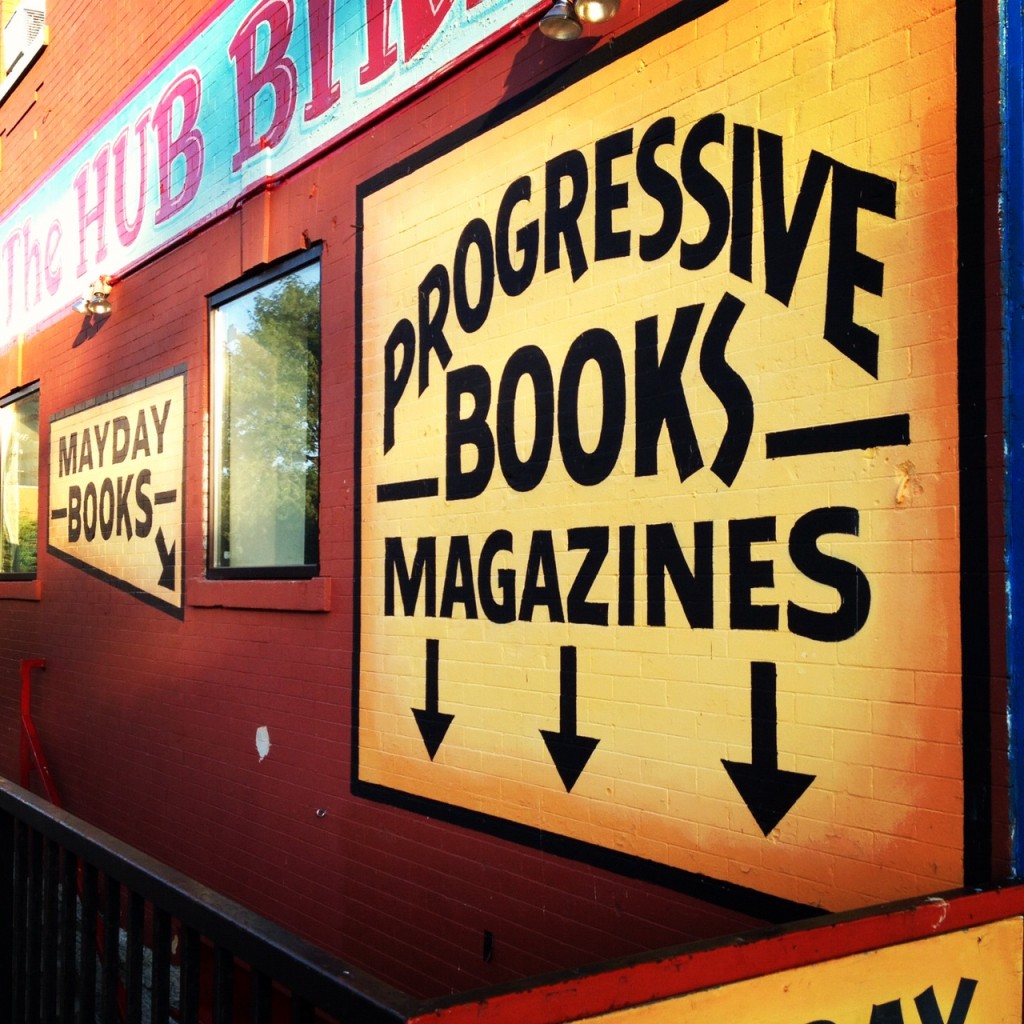

After a couple of days of consumerism and entertainment, I went for a walk near our hotel. First I found myself in a progressive independent bookstore in which a local social activism group was discussing which protests they should participate in. Then I wandered through a gritty, ethnic, low income neighbourhood, where my pale skin put me in the minority.

As I wandered, I found myself smiling. Though the shopping and amusement park had exhausted me, I found myself coming alive in this fascinating place where women in hijabs and men in long cloaks stood chatting in the streets. It reminded me once again how comfortable and energized I feel when I am in places where I don’t speak the local language or know the customs – places where it’s okay to be an edge-walker instead of a conformist.

This neighbourhood was as different from the mall or amusement park as it possibly could be. This neighbourhood showed its brokenness, its flaws, and its heartbreak. Most of all, though, it showed its heart.

Like my trip to Kensington Market a few months ago, I was reminded again how much better I fit in gritty, colourful, artful neighbourhoods than in places where shiny, happy people pretend that consumerism and entertainment will fill the empty spaces in their lives.

Our society likes shiny happy places. We like to gloss over the mess, fix the holes, and pretend the brokenness doesn’t exist. We pretend our relationships are fine, we put on happy faces in our social media interactions, we flock to “gurus” who will help us fix our lives in ten easy steps, we pretend grief can follow simple stages, and we seal ourselves off from relationships that get too messy.

But all of that shininess doesn’t make us come alive. It only makes us look like we’re alive. It’s like Weekend With Bernie – we’re already dead, but still propped up by lies that make us look like we’re having a great time at the party.

Real life is in the grit and the messiness. Real life is about embracing the shadow. It’s about diving into the depths of our grief instead of glossing over it. It’s about wrestling our way through difficult relationships to try to find the value under the layers of brokenness.

In a workshop I once did, I challenged the participants to consider what it meant to be authentic in their relationships. One woman struggled with the exercise I’d given them, and finally approached me about it. “I’m always authentic in my relationships,” she said. “If someone gets on my nerves, I just stop being in relationship with them.”

“That’s not exactly what I mean,” I said. “Stepping away from difficult situations is not what authenticity is about. Authenticity is about diving deeper into the brokenness and trying to find the oyster buried in the ugly clamshell. It’s about being real and living in such a way that others can be more real in our presence.”

Living authentically is not about fixing every flaw, abandoning every broken relationship, or following every self-improvement guru we can find to better ourselves. It’s also not about airing all of our dirty laundry in public.

Authenticity is about embracing the grit, celebrating the mess, living with discomfort now and then, stretching beyond our comfort zones, asking real questions, honouring our brokenness, and holding our place in community despite the difficulty it may bring.

by Heather Plett | Jul 25, 2012 | Uncategorized

A few weeks ago, my husband’s wallet was stolen from our van. Within the following week, about a dozen people stopped by our house, bringing with them pieces of Marcel’s identification that they’d found strewn around the neighbourhood. It was a strong reminder to me that for every one person in the world who will steal something, there are at least a dozen people who will go out of their way to make it right.

A few weeks ago, my husband’s wallet was stolen from our van. Within the following week, about a dozen people stopped by our house, bringing with them pieces of Marcel’s identification that they’d found strewn around the neighbourhood. It was a strong reminder to me that for every one person in the world who will steal something, there are at least a dozen people who will go out of their way to make it right.

This week, a dozen people were killed and many more injured in a horrific shooting in Aurora, Colorado. In the days that followed, many stories came out about the acts of heroism that took place in that theatre – people helping strangers and/or loved ones get to safety. Some people risked their own lives for people they’d never met. Once again I am reminded that there are more people doing good than evil.

As a response this tragedy, I have decided to do at least a dozen acts of kindness – one for each murder victim. These won’t necessarily be monumental acts like saving someone’s life, but I will make a concerted effort to go out of my way to spread kindness rather than hatred. I may plug someone’s parking meter, buy a gift for a stranger, or leave love notes on the mirrors of public washrooms. I believe that most of my acts will be anonymous, but I’m not sure what they’ll all be yet.

I’d love to have you join me in spreading this kindness. If at least a dozen people do a dozen kind acts, we’ll have far outnumbered that one act of evil.

The people killed were Veronica Moser-Sullivan, Jessica Ghawi, Alex Sullivan, Jonathan Blunk, John Larimer, Matt McQuinn, Micayla Medek, Jesse Childress, Jesse Childress, Alex Teves, Rebecca Ann Wingo, and Gordon W. Cowden. You may wish to attach their names to each act of kindness so that their legacy spreads in a kind way.

I’ve created a Facebook page for this cause. Please join me here.

Let’s spread love instead of hate, kindness instead of evil, hope instead of fear.

by Heather Plett | Jul 17, 2012 | growth

A lot of us (myself included) use the birth analogy when we’re bringing something new into the world. We talk about our newly formed businesses, freshly written books, or works of art as our “babies”.

I like the analogy, personally, but I think we often forget about some of the details of giving birth. We want to believe that once something is birthed, it’s ready for the world, but the truth is much different from that.

For starters, the birthing process starts nine months before the new being arrives. Yes, it may start out with an exciting encounter, but that moment is followed with months of waiting, preparing, vomiting, crying, worrying, and waiting some more.

Then when the time finally comes for it to be born, we have to go through hours of contractions, pain, more vomiting (or worse), interception if necessary, pushing, and crying. Sadly, sometimes the baby dies on his/her way into the world.

If we’re lucky enough to bring a living baby into the world, the new being that’s placed in our arms is beautiful, but it is far from being ready to walk on his/her own two feet. First there are months of sleepless nights, thousands of diaper changes, and endless floor-pacing. Every bit of our energy is suddenly usurped by this new person who’s been entrusted to our care. Every few hours, we must stop everything we’re doing to make sure the baby is fed. Yes, there are many beautiful moments of pure love and connection, but those come with a price and a whole lot of exhaustion.

Then, when the small person begins to walk, there is the need to be ever vigilant, lest the child swallows poison, bumps an elbow, or wraps a tiny hand around a curling iron. There are visits to the hospital, more sleepless nights, temper tantrums to deal with, and more exhaustion.

With each stage of childhood, the worries and concerns are different, but they never fully go away. We’re dealing with the teen years in our house, and I can assure you that vigilance is still very necessary, as is the need to break up many fights, console many broken hearts, and walk through a lot of unfamiliar territory.

When you’re tempted to get discouraged (as I often am) about a business that doesn’t feel like it’s getting off the ground soon enough, or a book that’s taking far too long to get written, or a new community group that just can’t seem to get its act together, remember to treat it like a baby.

Give it months to gestate and years to grow into the thing it’s meant to be.

Make sure you pause every few hours to give it (and yourself) nourishment.

Remember that rushing the process only results in stunted growth.

Sooth the broken hearts and bumped knees and remember that wounds heal.

In the middle of the hard times, remember that valuable lessons are being learned.

Let it emerge into its own life and don’t let your ego get too attached to the results.

Sit back and enjoy it whenever you can.

Spend lots of time on the floor playing with Lego or reading books.

by Heather Plett | Jul 10, 2012 | circle

Yesterday I had the privilege of participating in a sharing circle for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. A few years ago, our government apologized to our First Nations people for the injustice that had been done for generations, when young children were taken away from their families and forced to live in residential schools. These circles offer all of us an opportunity to seek healing as a country.

In the circle, we were asked to share how we had personally been impacted by residential schools, what we believe reconciliation means, and how our countries and communities can heal. Only a few of the people in the circle had been to residential schools themselves, but all of us have been impacted by the deep wounds our country bears.

I sat with tears in my eyes as I listened to the stories. One woman shared about how bewildered she’d been as a four year old when her older sister had disappeared from their home, and then how she too had one day disappeared. Another women talked about the abuse she’d suffered at the hands of her alcoholic husband who’d been a residential school survivor. A young man, who works as a videographer at sharing circles like this one, talked about how the priests and nuns at some of these schools had put needles into the tongues of children who were caught speaking their indigenous language while at school.

Almost every First Nations person who talked expressed the shame that the residential schools system had instilled in their culture. Whether they’d been to residential schools themselves or been raised by parents or grandparents who were survivors, each and every one of them carried the burden of being an oppressed people, made to feel less than their oppressors. It was a painful reminder that healing from oppression takes many generations.

As the talking piece rounded the circle, I wrestled with what I would offer into the circle. Did I have any right to say anything in the midst of this pain? And yet… did I have a right to remain silent?

An interesting thing happened around the diverse and multicultural circle. Those who shed the most tears were often the people of caucasian descent. It was clear that the shame in the circle was not only among the indigenous people. Those who are descendants of the oppressors also need to be healed from the pain that their ancestors have caused.

By the time the talking piece finally reached me, I knew what I needed to say.

“My name is Heather… and… more than anything, I don’t want to be racist. And yet… there is one thing I know and that is that reconciliation needs to begin with me. Before I can be part of the healing process, I need to peel away the layers of my own stories, find the seeds of the oppressor buried in me, and address them.”

It’s easy for me to say that the residential schools are not my burden to bear. I didn’t pull any children out of their homes or pierce their tongues with needles. I don’t need to carry the blame for that.

And yet… as the writers of The Shadow Effect remind me, we cannot escape the shadows of our ancestors. The darkness that was in them still exists in us. The shadow that caused them to take brutal action against others remains rooted in our culture and we cannot expect it to go away unless we address it head on.

We are all oppressors.

We are all colonizers.

We all have the shadow in us.

We can’t fight the shadow and we can’t bury it. The only way to address it is to befriend it, to peel away the layers that keep it hidden, look it directly in its face, and take the lessons we need to learn from it.

Here is a piece of my shadow that I hate to look at… I am a racist. I judge other people based on their race. I don’t do it overtly, and I fight desperately hard not to do it at all, but I know that when I see a homeless person on the street, or I sit on the bus next to someone who smells funny, a tiny little shadowy voice inside me whispers in my ear that it has something to do with their race. That’s what oppression does – it infects generations of descendants on both sides of the divide whether they want to admit it or not.

Recently I heard Bishop Desmond Tutu talk about the post-apartheid days in South Africa. He’d been a leader in the movement to end apartheid, but one day he realized how deep the roots of oppression had grown in his own heart. In an airplane one day, he’d discovered that the pilot was a black African man. His first thought was “Isn’t this great? We’ve finally arrived! We’re able to fly planes now!” But then, when the plane hit turbulence, the instantaneous thought that entered his mind was “is a black man capable enough to keep us safe?” That’s when he realized that deep in his heart, he’d let the oppressors convince him that his people had less value.

That’s how insidious oppression is. Even when we don’t recognize it, there can still be tiny hints of it that emerge in our most threatened or vulnerable moments.

When I look at the roots of my own personal battle with racism, I can find the stories in my past that helped it grow. When I was twenty one years old, I was raped by an Aboriginal man who smelled of glue and rubbing alcohol and had a large tattoo of a naked woman on his arm. He climbed through my window and destroyed my innocence and illusions of safety in my own home.

Now, as I look back at that event in my life, through the thickening lens of the many years that have passed, I can see how that pain story (and others like it) has contributed to the way that I have lived and the way I have treated people.

There are so many complex layers of pain in that story – both my pain and that of my rapist. That’s what oppression does – it builds layers of pain on us as individuals and us as communities of people, layers we can’t easily shake. My rapist, bearing the burden of addiction – most certainly as the result of the oppression he’d born and his ancestors had born before him – becomes the aggressor. The oppressed becomes the oppressor as he attempts to colonize women’s bodies through acts of rape and by tattooing their naked bodies on his skin. Pain is infectious – it wants to spread from one person to the next.

I, in turn, a child of privilege and a descendent of oppressors, in that moment became the oppressed – the victim. It’s a vicious cycle.

The next bit is the tricky part… do I let that pain story continue unchallenged? Do I justify my racism, and continue to look down my nose at the homeless First Nations people I encounter on the downtown streets? Do I toss everyone into the same category as my rapist? Do I continue the cycle of abuse?

Or do I take a good hard look at the shadow and see what I can learn from it?

This is not an easy story to tell. I want you to think that I have never acted out of racist intent – that I have been kind to every person I’ve met, regardless of their race or social status. I want you to believe that I am above that and have never perpetuated the cycle of abuse. I have very good relationships with people of many cultures and I try desperately hard to treat them all with respect and equality. In fact, in my university days, my best friend was a Aboriginal man, and I am now married to a Metis man. See? I have overcome the cycle! That’s the story I want you to know about me.

And yet… the shadow still emerges sometimes. I can’t deny it. I hurt people by not honouring their dignity. I let my fear keep me from looking people in the eyes sometimes. I avoid neighbourhoods where I might encounter my shadow.

As I sat in that circle last night, I wept for the pain that I had born and the pain that I had caused. I wept for the colonizers and the colonized. I wept for the pain stories that all of us carry and all of us continue to perpetuate, even in small and seemingly harmless ways. I wept for the shame of being a child of the oppressors. I wept for my rapist and for his family – for the pain they continue to carry. I wept… and then I offered an apology for all of the little ways that I had perpetuated the cycle.

Before it was my turn, two young Aboriginal men had shared their stories of trying to rise above the oppression and become leaders and change-makers in their communities. Their stories inspired me, and – more importantly – offered me one more piece of my healing journey. Seeing young men who are willing to stare down the shadow, rise above it, and bring their people’s pain stories into the light offered me a different paradigm for Aboriginal men than my rapist had imprinted on me. It was an honour to sit in circle with them.

After the circle had ended, I asked each of those men if I could give them a hug. They both were more than willing to accept. Perhaps in that gesture I have offered them a bit of healing too.

The last question each of us was asked to address was our thoughts on how our country will be healed. That question is far too big for me. I don’t know what it takes to heal a country and I don’t think anyone does.

I do know, however, that what heals me begins to heal a country. And the thing that will continue to offer me healing is the opportunity to sit in circle. Sitting in circles peels away the layers of hierarchy that we are all so used to in our culture. Sharing stories offers us the opportunity to see each other through new lenses. Befriending people who are different from us helps us shift our paradigms and change the world one friendship at a time.

Circles give us the chance to sit in equal positions, looking into each others’ eyes, listening deeply to each others’ stories, and re-building a bit of that trust that has been destroyed by so much of our history.

We need more circles. We need circles in our classrooms, circles in our governments, and circles in our homes. We need circles and we need friendship. That’s where healing begins.