by Heather Plett | Mar 13, 2018 | holding space

When my husband and I separated and he moved out of the house, my youngest daughter was 13, and she was, understandably, angry about a situation in which she had no agency to control the outcome. I tried to be present for her in as kind and compassionate a way as I knew how, while still wrestling with the healing work I also needed to do for myself. It was hard – for both of us. I made mistakes.

Finally, after weeks of very little communication between us, I said to her “I know you’re angry. You have every right to be. AND I want you to know that I am prepared to hold your anger. Go ahead – scream at me if you must. Do what you need to do, and know that I WILL NOT LEAVE. And I will not throw the anger back at you. I will just hold it for you.”

In that situation, I had to recognize that, as the person with more agency and power, who had contributed to a situation that impacted her, I had to be prepared to receive what would come my way, even if I didn’t entirely deserve it. Even if it hurt. Even if it scared me.

I had to be prepared to hold it and NOT WALK AWAY.

This, too, is what it means to hold space – to create a container that is strong enough to hold rage, grief, fear, pain, etc. We receive what’s ours, heal it, make reparations, and let the rest go. And we don’t walk away. (We take care of ourselves, but we don’t walk away.)

Let’s extrapolate that situation to other situations where there is an imbalance of power and agency. Take, for example, some of the conversations I’ve seen and been part of, both online and off, where there is understandable anger on the part of disenfranchised/marginalized people whose lives are being irrevocably altered by people with more power and agency. Online, I’ve seen it in response to a spiritual teacher who failed to listen when people challenged her to see her blindspots. Offline, I’ve heard it in response to the Colton Boushie and Tina Fontaine murder trials.

For those of us with more power and agency (whether given to us as a “birthright” because of our skin colour, gender, etc., or because we’ve found ourselves in a hierarchically elevated position) can we hold this outrage and pain without walking away? Can we be strong enough to stay in the conversations even if it hurts, even if it scares us, even if we don’t entirely deserve it? Can we receive what’s ours, heal it, and let the rest go?

This, to me, is what reconciliation looks like. Holding space, owning what’s ours, listening deeply, making reparations, and not walking away.

(The good news is that my daughter and I weathered that storm and have a deeper relationship now because of it.)

by Heather Plett | Jan 5, 2016 | Community, connection

In one of my favourite childhood photos, I’m sitting on the couch with a row of dolls lined up on my lap. Unfortunately, that photo was lost when my mom moved away from the farm after dad died, so it exists only in my memory now. The way my memory serves me, though, each of those dolls has a different skin colour, hair colour, and/or cultural attire. Only one of those dolls has blonde hair and blue eyes like me.

That’s the way I like to think of myself – from a young age choosing to surround myself with difference, with diversity. It’s not always true (in much of my life I have been surrounded by too much sameness), but it’s my ideal image of myself.

I thought of that photo recently when a viral video depicted two young white girls reacting in disappointment and disgust when they received black dolls as Christmas gifts. What’s most disturbing about that video is the way the adults giggle about and invite their reaction and the very fact that some adult thought it was funny enough to share online. Clearly their behaviour is a learned behaviour. Raised in another environment, those girls would likely have been delighted by the gift.

I have been disturbed lately by sameness and the way those girls’ actions too closely reflect our own. I see it in my own life and I see it in the world around me. We gravitate toward what is comfortable and safe, what looks and sounds like us, and so we end up in places, in conversations, and in friendships where there is a clear insider and a clear outsider. In doing so, we marginalize the people who don’t fit in. Without even knowing it, we toss aside the black dolls just as those young girls did.

Most of us are good people, so we don’t do it intentionally, but good people make mistakes when we don’t pay attention. Good people make mistakes when we see the world only through our own lenses.

Marginalized people get hurt by a lot of good people who “didn’t mean to hurt anyone”.

Let me be perfectly clear that I include myself in this critique. I like to be comfortable as much as the next person, and so I too often find myself in places and in relationships where the people in the room largely fall into the same racial, gender, and socio-economic categories as I do.

But we miss out on SO MUCH when we don’t listen to the voices of people who are different from us. We miss out on SO MUCH when we don’t challenge our own comfort levels and dare to stretch ourselves beyond what feels safe. We miss out on SO MUCH when we toss aside the beautiful black dolls.

When everyone in the room looks the same, someone’s left outside. Sometimes that’s okay (when we’re at a family gathering, or when we’ve come together for healing or empowerment, for example), but often it’s not.

Over the festive season, I participated in two spiritual gatherings. The first one (which I’ve written about before) was a small gathering in a hospital sanctuary, where people of diverse faiths each lit a candle and talked about what light means in their spiritual tradition. At that one, the room was full of diversity of every kind. Not only were there at least nine faith groups represented in those who lit candles (most of whom were people of colour from various parts of the world), but there were hospital patients in wheelchairs and people of all walks of life, with varying degrees of health, socio-economic status, and physical ability.

I left that gathering feeling energized and connected to God/dess.

The other gathering I attended was on Christmas Eve, in Florida where my family was vacationing. This was a traditional Christian service that was fairly similar to what I grew up with. Though the setting was very different (this was a large posh church with theatre-style seating, while I grew up in a tiny and poor country church with old wooden pews), the language was largely the same. There was some comfort in that sameness – I knew the Christmas carols and had heard the Christmas story hundreds of times. It was a perfectly lovely service, with great singing and good story-telling on the pastor’s part. One story he shared was quite moving – about how a large endowment to the church had been split up among church-goers who were told to go out and do some act of kindness in the community.

Unlike the gathering in the hospital sanctuary, there was very little diversity in the room. In a room filled with more than a thousand people, I saw only three people of colour and could see evidence of very little socio-economic diversity. Among the visible leadership, there was even less diversity. The only people who spoke or served communion were older white men. Either you received God’s teachings and God’s body and blood from an older white man, or you didn’t receive it at all.

I left that gathering feeling weary and disconnected from God/dess.

I have no doubt that the church-goers and their leaders are good people doing good work in their community. They don’t mean to exclude anyone, and there’s a good chance they have well-meaning conversations about how to increase their diversity and how to reach out to people who are different from them. I know many good people like them, and in many ways, I am one of them – good people trying to do good things.

But good people hurt other people by living their good, comfortable lives and ignoring their own privilege and narrow views of the world.

And this is not a domain that’s exclusive to a conservative Christian church by any means. It happens in all kinds of settings.

Recently I was looking at an online advertisement for a women’s leadership summit – the kind of event I’d normally be drawn to, where leadership is seen through a feminine lens and there’s a comfort level with talk of the feminine divine and women’s power. But there was something about it that left me feeling sad, and I realized it was because of the sameness of the images on the speakers’ list. All of them were white women between the ages of 30 and 50 who looked like they’d stepped out of the pages of a yoga magazine.

Just what the patriarchy has for so long done to them, the organizers of this online summer were, (inadvertently of course) doing to others – marginalizing the voices of those who don’t fit. I’m sure these women would have all been horrified by the video of the young white girls tossing aside the black dolls, but in a way, the result was the same.

Sameness. Comfort. Marginalization. Barriers. Disconnection.

What do we do about it? That’s a big conversation and it needs the voices of many people who see the world differently from me.

I can only offer my own perspective from where I stand.

We start by noticing. We start by paying attention – looking around the room to see who’s sitting with us, checking our social media feed to see who we’re conversing with, noticing the books we read and the voices we listen to, paying attention to who has a voice at our gatherings. Because if we’re not listening to the stories of people who are different, if we’re not sitting and having conversations with them, we’ll always be stuck in this same place.

I loved Gloria Steinem’s recent book, My Life on the Road, largely because she shares so many stories about how she was influenced and changed by the people she met on the road. Much of her wisdom came not from people who look like her, but from black people, indigenous people, bikers, and farmers. She is the woman she is today because all of these people’s stories have been woven into her own.

I’m here to challenge us all to live more like that. Let’s be the kind of people who listen to stories and wisdom of people who look, think, and live differently from us. Let’s read books from other parts of the world and written by people of other races and classes. Let’s have more conversations with people who don’t share our political views or our socio-economic status.

I’ve created a list of books written by people who’ve lead very different lives from mine that I want to read and I’m working my way through them. Some I’ve read recently and recommend are Wab Kinew’s The Reason You Walk, Rosanna Deerchild’s Calling Down the Sky, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah. I encourage you to build your own list.

I’ve also signed up for a course called “How to Embrace Diversity to Improve your Business” being offered by Desiree Adaway and Ericka Hines. Quite frankly, there is still too much sameness in the kind of clientele I attract and I want to see what I can do to change that. I know that Desiree and Ericka will challenge me and hold me accountable, and though it may be uncomfortable sometimes, I’ll do my best to stretch myself.

What else can we do to shift the status quo? Good people, I look forward to hearing from you.

by Heather Plett | Aug 29, 2014 | mandala, Uncategorized

This is a re-share from back in February. I’m bringing it forward again, partly because Mandala Discovery starts again September 1st, and partly because the topic seems timely for some of the things going on in the world around us right now.

Last week I attended a vigil for two people whose bodies had been found in the river. Both were First Nations. Both were living marginalized lives, victims of generations of injustice. One was a homeless man who struggled with addiction. He was known in our city as the Homeless Hero because he’d saved two people from drowning a few years before his own life ended in the same river. The other was a 15 year-old-girl who ran away from a foster home, was exploited and then murdered.

At the same time, in the U.S., the passionate response to a young black man’s death at the hands of the police in Ferguson continues to remind us that the world does not treat all young men equally.

As a woman born into white privilege, I did not “earn” better treatment than any of these three people did, and yet it is almost certain that I would have been treated better in almost every circumstance than any of these three people were. It’s not fair, and I can feel helpless in the face of it and choose to hide my head in the sand and pretend it doesn’t matter, or I can choose to be awake to what I see, choose to be honest about where the problems are, and choose to own my lineage with all its flaws and imbalances.

We all have our historic stories that feed into who we are and how we walk in the world. I come from a Mennonite heritage, and so I carry with me the roots of pacifism and stories of the abuse my ancestors faced in Russia because of it. Those stories may feel far away, and yet they are part of who I am.

If you want to explore your own roots, here’s a Mandala Journal process that might help you do that.

If this feels meaningful to you and you’d like to receive a prompt like this in your inbox once a day for 30 days, sign up for Mandala Discovery, starting September 1st.

Where Your Roots Grow

A couple of years ago, I had the privilege of participating in a healing circle for people who’d been impacted by residential schools in our country. This is a tragic chapter of Canada’s history in which Aboriginal children were taken from their families and placed in boarding schools where they were denied their own cultural practices and language, and many were physically and emotionally abused.

A few of the people in the circle had been students at residential schools, but more of them had been raised by parents who were forced to attend residential schools. And then there were those of us who didn’t have residential schools in our blood line, but knew that we were impacted nonetheless, because our community members were impacted and because we were raised as white Canadians with a colonial history. Some of our ancestors undoubtedly shared in the guilt of this injustice.

As we listened to the stories shared around the circle, it was clear that all of us carried both the wounds and the wounding of our ancestors. It was especially apparent in those who’d been raised with parents who’d been in residential schools. Some of them spoke of alcoholism, family abuse, cultural neglect, and other stories that clearly left deep wounds in their collective psyche.

Whatever our roots are – whether we were raised in a lineage of oppressed or oppressors, religious or agnostic, poverty or wealth – we all carry the stories of our ancestors with us.

Our roots reach much deeper into the soil of our family’s past than we ever fully understand. We are impacted by the history that happened in our bloodline long before we were conceived and born into this world.

Bethany Webster talks about the importance of healing the mother wound. “The mother wound is the pain of being a woman passed down through generations of women in patriarchal cultures. And it includes the dysfunctional coping mechanisms that are used to process that pain.” The mother wound manifests itself in our lives as shame, comparison, the feeling that we need to stay small, allowing ourselves to be mistreated by others, and self-sabotage. If we do not heal it, she says, we continue to pass this wound down through the generations.

We must also consider the ways in which patriarchy has impacted men. As Richard Rohr says, “After 20 years of working with men on retreats and rites of passage, in spiritual direction, and even in prison, it has sadly become clear to me how trapped the typical Western male feels. He is trapped inside, with almost no inner universe of deep meaning to heal him or guide him.” Men have to come to terms with their own wounds and often have little support to find healing for them.

These stories that we carry from our past – that we are not worthy, that we need to stay small, that we are not allowed to show emotion, that our cultures don’t have as much value as that of our colonizers, or that we are not allowed to do anything that goes against our religion for fear of hell – they are the soil in which our roots grow. If that soil is not fertile and nurturing, our growth is impaired and we never reach our full potential.

Imagine, though, that through an alchemical process, these stories can be healed and transformed and can become the fertile soil we need for healthy growth. Imagine that they can provide rich fertilizer to feed our roots and make our branches grow and our fruit to be plump and sweet.

We can transform these stories. They do not need to keep us small. They do not need to hold us back from what we can become.

Through much inner work – whether that looks like therapy, journaling, dance, meditation, mandala-making, or any other form of self-discovery and healing – we can cultivate those stories and stir them like a compost heap until they become the richest of fertilizer. This is not easy work, and it is not short-term work, but it is necessary work. The world needs us to heal and the world needs us to grow strong and true.

After reading the article by Bethany Webster, about the need to heal the Mother Wound, I wrote a letter to my mom. She died last year, so she won’t read it on this earth, but I still felt like there were some things I needed to say to her. I acknowledged the way that she had been wounded (by losing her mother when she was six, for example) and forgave her for the way that those wounds were passed on to me. I thanked her for the love she poured on me and my siblings despite the deep wounds she carried. Writing the letter felt significant – like I had begun to heal something for both myself and for her. There is more work to do, but every step toward healing is a step in the right direction.

Consider what Charles Eisenstein says about how our healing can contribute to the world’s healing (in “The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know is Possible”):

“When I see how my friend R. has, in the face of near-impossible odds, so profoundly healed from being abused as a child, I think, ‘If she can heal, it means that millions like her can too; and her healing smooths the path for them.’

“Sometimes I take it even a step further. One time at a men’s retreat one of the participants showed us burn scars on his penis, the result of cigarette burns administered by a foster parent when he was five years old to punish him. The man was going through a powerful process of release and forgiveness. In a flash, I perceived that his reason for being here on Earth was to receive and heal from this wound, as an act of world-changing service to us all. I said to him, ‘J., if you accomplish nothing else this lifetime but to heal from this, you will have done the world a great service.’ The truth of that was palpable to all present.”

Eisenstein goes on to talk about scientific research into “morphic resonance” in nature – the concept that once something happens somewhere, it induces the same thing to happen elsewhere. Some substances, for example, are reliably liquid for many years until suddenly, around the world, they begin to crystallize. It is not clear why it happens, when these substance are not in contact with each other or exposed to the same environment, but it seems that a change to one begins to result in changes to others. In the same way, he says, the healing of one person can lead to the healing of others, even if those people never meet.

Transforming your stories into rich soil so that you can grow strong is necessary not only for you, but for the world.

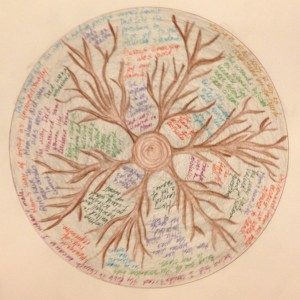

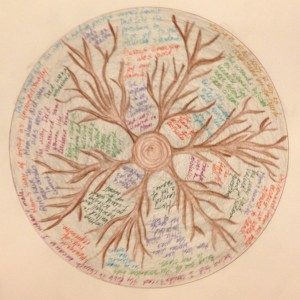

Your Roots Mandala

Imagine you are a tree, firmly rooted in the stories of your past. Some of these stories are conscious for you (memories from childhood) and some are less conscious but you are impacted by them nonetheless.

Begin by drawing a large circle. In the centre of the circle, draw a small circle that represents the trunk of a tree. Reaching out from that trunk into the fertile soil around it, draw the roots of that tree. (Imagine you are looking down on the tree from above and can only see that part of the tree that is underground, not the branches or leaves.)

Between the roots, write down stories that are part of your past. Start with the stories that you know have impacted you and your growth in both positive and negative ways. Your religious upbringing, your father’s temper, your mother’s insecurity, your grandmother’s way of making you feel special, your birth order, your childhood abuse, etc. Do not censor yourself – if a story shows up, there’s a good chance it had an impact on you whether or not you recognize it. (There is no right or wrong way to do this – your stories are your own and you know what matters to you.)

Between the roots, write down stories that are part of your past. Start with the stories that you know have impacted you and your growth in both positive and negative ways. Your religious upbringing, your father’s temper, your mother’s insecurity, your grandmother’s way of making you feel special, your birth order, your childhood abuse, etc. Do not censor yourself – if a story shows up, there’s a good chance it had an impact on you whether or not you recognize it. (There is no right or wrong way to do this – your stories are your own and you know what matters to you.)

Reach further back. What are the stories that impacted your lineage before you were born? Your family’s displacement from the country they called home, your grandmother’s abusive marriage, your ancestors’ connection to colonialism or oppression, your grandfather’s death when your mother was small.

Write them all down. Some of them may bring up pain, and some may bring up positive memories. Some may have a clear impact on your life, and some you may not fully understand until a much later date. They are all part of your narrative and they are all part of the soil in which your roots dig for nourishment.

With a black pencil crayon, shade over the stories you have written, imagining that all of them are now becoming part of the compost that helps you grow. Whether good or bad, those stories are your soil.

Note: This exercise may bring up a lot of mixed emotions for you. It may feel like a little bit of healing, or it may feel like you’ve opened a wound that is still raw. That’s all part of the healing process. Sit with whatever comes up and do not try to suppress it. If you need to, do some further journaling to explore what came up, or find someone you trust that you can talk to about this.

You can find a downloadable pdf of this lesson here.

Did you find this useful? Consider signing up for the September 2014 offering of Mandala Discovery: 30 Days of Mandala Journaling. You’ll get 30 more like this.

Between the roots, write down stories that are part of your past. Start with the stories that you know have impacted you and your growth in both positive and negative ways. Your religious upbringing, your father’s temper, your mother’s insecurity, your grandmother’s way of making you feel special, your birth order, your childhood abuse, etc. Do not censor yourself – if a story shows up, there’s a good chance it had an impact on you whether or not you recognize it. (There is no right or wrong way to do this – your stories are your own and you know what matters to you.)

Between the roots, write down stories that are part of your past. Start with the stories that you know have impacted you and your growth in both positive and negative ways. Your religious upbringing, your father’s temper, your mother’s insecurity, your grandmother’s way of making you feel special, your birth order, your childhood abuse, etc. Do not censor yourself – if a story shows up, there’s a good chance it had an impact on you whether or not you recognize it. (There is no right or wrong way to do this – your stories are your own and you know what matters to you.)