by Heather Plett | Jan 30, 2015 | books, Labyrinth

A few nights ago, I was reading in bed when my husband turned to me and said “It must be a good book. You haven’t taken your nose out of it all evening.” He was right – it IS a good book. It’s called Pilgrimage of Desire: An Explorer’s Journey Through the Labyrinths of Life by Alison Gresik. Reading it was like getting cozy in front of the fire with a glass of wine and an old friend who knows your thoughts before you even speak them. Let’s just say Alison and I have a LOT in common.

A few nights ago, I was reading in bed when my husband turned to me and said “It must be a good book. You haven’t taken your nose out of it all evening.” He was right – it IS a good book. It’s called Pilgrimage of Desire: An Explorer’s Journey Through the Labyrinths of Life by Alison Gresik. Reading it was like getting cozy in front of the fire with a glass of wine and an old friend who knows your thoughts before you even speak them. Let’s just say Alison and I have a LOT in common.

I was delighted when Alison got in touch with me (because she saw the parallels between her book and The Spiral Path). We arranged a Skype chat and then decided to interview each other on our blogs. I love her answers to my questions, because even though we think alike and both gravitate toward labyrinths and the Feminine Divine, we both bring something fresh to the narrative that helps us see things in new ways.

1. Tell me about your discovery of the labyrinth and how it helped you reframe your life’s journey.

My first memorable experience with the labyrinth was at a women’s retreat just before I turned 30. I was feeling quite anxious, depressed, and alone — I had been reading some feminist spirituality, Sue Monk Kidd and Carol Christ, and I felt like my image of God had been pulled out from under me.

We walked the labyrinth outside, as the evening was moving toward dusk. I had written down an intention to carry with me to the centre — I wanted God to give me a new name for herself, one that captured her feminine aspect but that also connected to the God of my youth. I was quite fearful that nothing would happen, but I actually had a powerful experience of meeting the Divine there, and receiving a name to call her: Amma.

The ritual around the labyrinth — the pattern marked on the grass, the lanterns, the women walking with me and holding the space outside — provided a strong and visible support for the encounter I had. Actually, I was so freaked out by how powerful the labyrinth experience was that it was a long time before I walked one again — I certainly didn’t make it a habit early on!

I didn’t come to see the labyrinth as a way of understanding my life’s journey until I wrote my memoir. Our year of travel had come to an early unexpected end, and we had settled in Vancouver, BC, where my husband took a job. And I was having a terrible time getting my bearings. It was one of the first major life decisions we’d made without months and years of preparation and choice, and even though it was a good place to be, I felt lost.

I had made several aborted attempts to walk labyrinths when we were in Europe during our year of travel, but something always kept going wrong. And finally, after a year in Vancouver, I was able to walk the Labyrinth of Light on Winter Solstice, which gave me a chance to say goodbye to everything that I’d left behind, to leave a totem of my grief in the centre (actually a lot of snot and tears on my sweater sleeve), and to emerge into this new phase of my life with a lightened heart.

Writing about the last ten years helped me see and make sense of the recurring patterns, the reversals and progress. The geometry of the labyrinth comforted and bolstered me in very tangible ways – physically and metaphorically.

2. Your book is called Pilgrimage of Desire: An Explorer’s Journey Through the Labyrinths of Life (which sounds a LOT like something I’d write, by the way). Can you tell me about the relationship between labyrinth journeys and desire? What does the labyrinth teach us about desire?

I think that desire is what moves us through the labyrinth. There must be something that compels us, draws us forward or pushes us on, and I believe that is desire, a deep urge to go from one place to another. If we don’t want something — if our heart doesn’t want to beat, if our lungs don’t want air — then we’re not alive. And the labyrinth channels and directs that movement, that desire, in its mysterious unfolding path.

I think that desire is what moves us through the labyrinth. There must be something that compels us, draws us forward or pushes us on, and I believe that is desire, a deep urge to go from one place to another. If we don’t want something — if our heart doesn’t want to beat, if our lungs don’t want air — then we’re not alive. And the labyrinth channels and directs that movement, that desire, in its mysterious unfolding path.

Just today I was reading a quotation from Goethe that says, “Desire is the presentiment of our inner abilities, and the forerunner of our ultimate accomplishments.” In other words, desire is our drive to unfold to our full potential. So while the object of our desire might take the shape of something material — a career, a lover, a child, a creative work, a travel destination — underneath it’s a desire to become what we can become.

And the labyrinth helps us trust and follow that desire. It holds our faith and helps us feel safe in a process that can be terrifying.

3. In the book, you mention the concept of “containers of meaning” (correct me if I got the term wrong). I haven’t heard that term before and it intrigues me. It seems to me that both you and I see the labyrinth as a “container of meaning” in our lives. First, explain the term, and then talk about how the labyrinth serves as a container of meaning.

“Meaning container” is a term I learned from Eric Maisel, and essentially it’s anything — an activity, a relationship, a project — that we designate to hold meaning for us. What we do and what we have assume greater significance because they are poured into a meaning container, captured and gathering weight rather than draining away.

I love the labyrinth as a meaning container, because it’s not a static bucket — it’s got flow and change. The labyrinth’s cycles can embrace the meaning of one hour, one day, and an entire life. So for me, the labyrinth holds the significance of that first walk and my connection with Amma, and now it holds my memoir and the story of living and writing it, and it also holds the whole history and symbolism of the feminine. The labyrinth shows me synchronicity — like you and I discovering each other! It’s like a code that communicates volumes in a single image. I feel like I’ve only begun to scratch the surface of what the labyrinth can mean to me.

4. One of the other things you and I have in common is an evolving relationship with the Divine, starting with the traditional Christian view we were raised with and emerging into something different. How did your journey to the feminine Divine change your faith?

In practice, maybe not too much. I still attend an Anglican church, I sing in the choir, and I talk to God in my journal and in my head. I love being part of a community with traditions that celebrate the seasons of the year.

What did change was the tenor of my relationship with God, when she revealed herself as Amma. Leaving behind the judgmental image of a patriarchal God and identifying with Amma as female and as a mother helped me know myself as loved in a way that I hadn’t before. I never felt the need to please Amma, I just knew she thought I was perfect and wanted the best for me. And of course it wasn’t God who changed, just my perception of her. I was able to let her in and be vulnerable with her.

I found this passage in my journal from just before meeting Amma: “I have a fear of exploring being a woman, that I don’t deserve to. That I might be a usurper. Why should I get to enjoy the healing that feminism can provide, if I haven’t been wounded by the patriarchy? Or am I afraid that if I look to closely, I will find those wounds? And even if I find them, wouldn’t other women laugh at them and say, that’s not nearly as bad as what I’ve been through. Those feelings of undeservedness and fear tell me that there’s definitely something up with this feminism thing for me. To think that I’m undeserving of it means I think it’s a good thing. To fear it means that I see it as powerful and life-changing. So those are reasons to keep an open mind, keep reading, and look for the Goddess.”

So coming to Amma was an initiation into the tribe of women that I’d never seen myself as a part of, and that encounter made me care a lot more about the ways gender affects our lives as humans.

5. In the book, you share a very personal account of the complexity of your relationship with your mom and your own experience of the “mother wound” (something that I was wrestling with as I watched my own mom die). Tell me about the experience of writing that so honestly and then taking the courageous step to share it with the world (including your family).

I knew from the beginning that my relationship with my mother was a very important part of the story I wanted to tell about claiming my right to be a writer. And I gave myself permission in the beginning to put everything I wanted to in the book and then sort out all the details later. I had the confidence to do this because I had a wonderful editor (Brenda Leifso) who I really trusted to help me walk the line between what served the story and what was just petty and unkind.

But honestly, when some of the events of our trip were happening as I was writing about it, particularly this conflict with my mom when we were in Detroit, I thought, never in a million will I write about this. I could never expose myself and her like that. And then the process of writing the book showed me what those events meant, and how they connected to what had happened in the past, and I could see they were part of the whole cloth of the story – I couldn’t cut them out.

I already had my parent’s blessing to write about the more ancient history in our family, particularly because we all saw the book as a means of helping others with similar struggles. So we built on that foundation when it came to working through more current events. In fact, the method we arrived at was that I would read them a chapter a week over a video call, because hearing it in my voice and seeing my emotion helped them process it better. Then they would respond, offer their perspective on events, correct my memory in places.

The saving grace, I think, is that my parents know we all have our own take on what happened, and they believe I’m entitled to tell my version. I feel very lucky that they can be that generous.

(By the way, if you want to read a pair of books that get even deeper into the workings of writing about one’s parents, I can highly recommend Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and Are You My Mother?)

In the end I suppose I get my nerve to publish from the belief that this book wanted to be a thing. Pilgrimage of Desire came knocking and I signed on for the ride. I’m just beginning to see the impact the book has on its readers, and I already know that it’s been worth it.

Alison’s book, Pilgrimage of Desire, is now available to order. Go buy it! Trust me on this – you won’t regret it!

Also, go check out Alison’s post where the tables were turned and she interviewed me.

by Heather Plett | Jan 29, 2015 | Uncategorized

Today I was handed a drum, and that may be the most important thing that happens to me all week. Maybe even all year.

All week, I have been wrestling with what my role is in the healing and reconciliation in our city. Because it matters. Because I want to live in a place of love. Because sometimes I hide my head in the sand and stay in my suburban bubble.

I have been immersing myself in stories, conversations, and learning about what brought us here, to this place, where we are called “the most racist city in Canada”. And I have been searching my own heart for what I need to address in order to be a “wounded healer”, to help invite a new narrative. Tears have been shed over the stories of abuse at the hands of my ancestors. And tears have been shed over my own complicating stories – like the day an Indigenous man climbed through my window and raped me, and the journey it took to once again walk down the street without seeing every Indigenous man on the street as my rapist.

Today I attended the weekly sharing circle at the Indigenous Family Centre. Though I’ve been there before, I was feeling nervous, made more painfully aware of the colour of my skin by the many stories in the media. I was afraid I didn’t belong, afraid I look too much like the oppressor with my white skin, afraid I might be challenged to face my own prejudice in that circle, and maybe even a little afraid I might be triggered back to the 21 year old version of me, cowering in my bedroom with the rapist standing over me.

I went anyway, because I have to start with me.

We started with a smudge – a tradition I have come to love over the years. Then one of the leaders picked up one of the drums in the centre of the circle, and walked toward me. Without fanfare, without words, he simply handed it to me. And when he started drumming and singing, I drummed with him. Our drums beat together, like the pounding heartbeat of Mother Earth beneath us. He didn’t care if I didn’t have rhythm or if I didn’t have the right colour of skin, he simply wanted me to be part of that pounding heartbeat.

That simple gesture cracked my heart open. No longer was I the white woman, the stranger, the oppressor. No longer was I “other”. I was simply a member of the circle, holding my place with everyone else.

And now I ask myself… how will that gesture of welcome and grace change me? How will I practice the same radical act of kindness, forgiveness, and community? How will I hand others the drum when they come to the circles I host?

by Heather Plett | Jan 28, 2015 | art of hosting, change, growth, journey, Leadership

“The success of our actions as change-makers does not depend on what we do or how we do it, but on the inner place from which we operate.” – Otto Sharmer

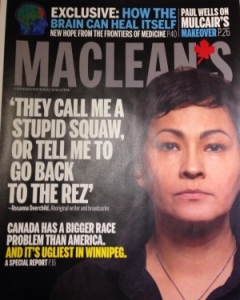

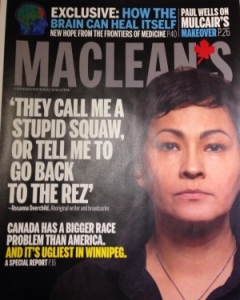

Last week, the city that I love and call home was named “the most racist city in Canada.” That hurt. It felt like someone had insulted my family.

Last week, the city that I love and call home was named “the most racist city in Canada.” That hurt. It felt like someone had insulted my family.

The article mentions many heartbreaking stories of the way that Indigenous people have been treated in our city, and while I wanted to say “but… we’re so NICE here! Really! You have to see the other side too!” I knew that there was undeniable truth I had to face and own. My family isn’t always nice. Neither is my city.

Though I work hard not to be racist, have many Indigenous friends in my circles, and am married to a Metis man, I knew that my response to the article needed to not only be a closer look at my city but a closer look at myself. I may not be overtly racist, but are there ways that I have been complicit in allowing this disease to grow around me? Are there things that I have left unsaid that have given people permission for their racism? Are there ways in which my white privilege has made me blind?

Ever since the summer, when I attended the vigil for Tina Fontaine, a young Indigenous woman whose body was found in the river, I have been feeling some restlessness around this issue. I knew that I was being nudged into some work that would help in the healing of my city and my country, but I didn’t know what that work was. I started by carrying my sadness over the murdered and missing Indigenous women into the Black Hills when I invited women on a lament journey.

Ever since the summer, when I attended the vigil for Tina Fontaine, a young Indigenous woman whose body was found in the river, I have been feeling some restlessness around this issue. I knew that I was being nudged into some work that would help in the healing of my city and my country, but I didn’t know what that work was. I started by carrying my sadness over the murdered and missing Indigenous women into the Black Hills when I invited women on a lament journey.

This week, after the Macleans article came out, our mayor made a courageous choice in how he responded to the article. In a press conference called shortly after the article spread across the internet, he didn’t get defensive, but instead he spoke with vulnerability about his own identity as a Metis man and about how his desire is for his children to be proud of both of the heritages they carry – their mother’s and his. He then invited several Indigenous leaders to speak.

There was something about the mayor’s address that galvanized me into action. I knew it was time for me to step forward and offer what I can. I sent an email and tweet to the mayor, thanking him for what he’d done and then offering my expertise in hosting meaningful conversations. Because I believe that we need to start healing this divide in our city and healing will begin when we sit and look into each others’ eyes and listen deeply to each others’ stories.

After that, I purchased the url letstalkaboutracism.com. I haven’t done anything with it yet, but I know that one of the things I need to do is to invite more people into a conversation around racism and how it wounds us all. I have no idea how to fix this, but I know how to hold space for difficult conversations, so that is what I intend to do. Circles have the capacity to hold deep healing work, and I will find a way to offer them where I can.

Since then, I have had moments of clarity about what needs to be done next, but far more moments of doubt and fear. At present, I am sitting with both the clarity and the doubt, trying to hold both and trying to be present for what wants to be born.

Here are some of the things that are showing up in my internal dialogue:

- Isn’t it a little arrogant to think I have any expertise to offer in this area? There are so many more qualified people than me.

- What if I offend the Indigenous people by offering my ideas, and become like the colonizers who think they have the answers and refuse to listen to the wisdom of the people they’re trying to help?

- There are already many people doing healing work on this issue, and many of them are already holding Indigenous circles. I have nothing unique to contribute.

- What if I host sharing circles and too much trauma and/or conflict shows up in the circle and I don’t know how to hold it?

- What if this is just my ego trying to do something “important” and get attention for me rather than the cause?

And so the conversation in my head goes back and forth. And the conversations outside of my head (with other people) aren’t much different.

At the same time as this has been going on, I have been working through the first two weeks of course material for U Lab: Transforming Business, Society and Self. In one of the course videos, Otto Sharmer talks about the four levels of listening – from downloading (where we listen to confirm habitual judgements), to factual (listening by paying attention to facts and to novel or disconfirming data), to empathic (where we listen with our hearts and not just our minds), and finally to generative (where we move with the person speaking into communion and transformaton).

As soon as I read that, I knew that whatever I do to help create space for healing in my city, it has to start with a place of deep listening – generative listening, where all those in the circle can move into communion and transformation. I also knew, as I sat with that idea, that that generative listening has to begin with me.

If I am to serve in this role, I need to be prepared to move out of my comfort zone, into generative listening with people who have been wounded by racism in our city AND with people who live with racial blindspots. AND (in the words of Otto Sharmer) I need to move out of an ego-system mentality (where I am seeking my own interest first), into a generative, eco-system mentality (where I am seeking the best interest of the community and world around me).

So that is my intention, starting this week. I already have a meeting planned with an Indigenous friend who has contributed to, and wants to teach, an adult curriculum on racism, to find out how I can support her in this work. And I will be meeting with another friend, a talented Indigenous musician, about possible partnership opportunities. And I will be a sitting in an Indigenous sharing circle, listening deeply to their stories.

I am not sharing these stories to say “look at me and all of the good things I’m doing”. That would be my ego talking, and that’s one of the things I’m trying to avoid. Instead, I’m sharing it to say “look at the complexity that a thinking woman (sometimes over-thinking woman) goes through in order to become an effective, and humble, change-maker.

That brings me back to the quote at the top of the page.

“The success of our actions as change-makers does not depend on what we do or how we do it, but on the inner place from which we operate.” – Otto Sharmer

The inner place. That is what will determine the success of our actions. I can have all the smart ideas in the world, and a big network of people to help roll them out, but if I have not done the internal work first, my success will be limited.

If I don’t do the inner work first, then my ego will run rampant and I will stomp all over the people that I say I care about. Or I will suffer from jealousy, or self doubt, or self-centredness, or vindictiveness, or all of the above.

If I don’t do the internal work and ask myself important questions about what is rooted in my ego and what is generative, then I could potentially do more harm than good.

So how do I do that internal work? Here are some of the things that I do:

1. As we say in Art of Hosting work, I host myself first. In other words, I ask of myself whatever I would ask of others I might invite into circle, I look for both my shadows and my strengths, and I do the kind of self-care I would encourage my clients to do when they find themselves in the middle of big shifts.

2. I ask myself a few pointed questions to determine whether the ego is too involved. For example, when my friend came to me to share the work she wants to do, hosting circles in the curriculum she has developed, there was a little ego-voice that spoke up and said “But wait! This was supposed to be YOUR work! If you support her, you’ll have to be in the background.” The moment I heard that voice, I had to ask myself “do you truly want to make a difference around the issue of racism or do you just want to make a name for yourself?” And: “If this is successful in impacting change, but you have only a secondary role, is it still worthwhile?” It didn’t take long for me to know that I wanted to be wholeheartedly behind her work.

3. I pause. As we learn in Theory U, the pause is the most important part – it’s where the really juicy stuff happens. The pause is where we notice patterns that we were too busy to notice before. It’s where the voice of wisdom speaks through the noise. It’s where we are more able to sink into generative listening. In Theory U, we call it “presencing” – a combination of “presence” and “sensing”. There’s a quality of mindfulness in the pause that helps me notice and experience more and be awake to receive more wisdom.

4. I do the practices that help bring me to wise thought and wise action. For me, it’s journaling, art, mandala-making, nature walks, and labyrinth walks. I never make a major decision without spending intentional time in one of those practices. Almost always, something more profound and wise shows up that I wouldn’t have considered earlier.

5. I listen. The ego doesn’t want me to seek input from other people. The ego wants to be in control and not invite partners in to share the spotlight. If I want to move out of ego-system, though, I need to spend time listening for others’ stories and wisdom. This doesn’t mean I listen to EVERYONE. Instead, I use my discretion about who are the right people to seek wise council from. I listen to those who have done their own personal work, whose own egos won’t try to trap me and keep me from succeeding, and who genuinely care about the issue I’m working on.

6. I check in with myself and then move into action when I’m ready. Although the pause, the questions, and the personal practice are all very important, the movement into action is equally important. There have been far too many times when my questions and ego have trapped me in a spiral and I’ve failed to move into action. Just thinking about it won’t impact change. I need to be prepared to act, even if I still have doubt. If I fail in that action, I can always go back and re-enter the presencing stage.

This is an ongoing story and I hope to continue sharing it as it emerges. If you, too, want to become a change-maker, then I’d love to hear from you. What are the processes you go through in order to ensure your “inner place” is healthy and your listening and actions are generative? What issues are currently calling you into action?

If this resonates with you, check out The Spiral Path, which begins February 1st. Based on the three stages of the labyrinth, (release, receive, and return), it invites you to go inward to do this internal work and then to move outward to serve in the way that you are called.

Also… we’re looking for a few more change-makers to attend Engage, a one-of-a-kind retreat that will teach you more about how to do your inner work so that you can move into generative action.

by Heather Plett | Jan 22, 2015 | beauty, Wisdom, women

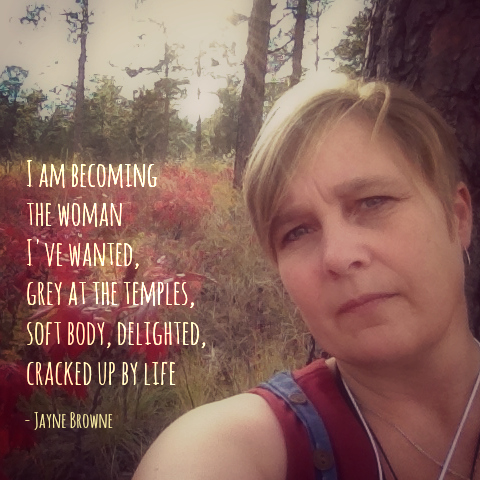

Last night I hosted a circle of women on Skype, and at the beginning of the call I read this poem:

Finding her here

by Jayne Brown

I am becoming the woman I’ve wanted,

grey at the temples,

soft body, delighted,

cracked up by life

with a laugh that’s known bitter

but, past it, got better,

knows she’s a survivor–

that whatever comes,

she can outlast it.

I am becoming a deep

weathered basket.

I am becoming the woman I’ve longed for,

the motherly lover

with arms strong and tender,

the growing up daughter

who blushes surprises.

I am becoming full moons

and sunrises.

I find her becoming,

this woman I’ve wanted,

who knows she’ll encompass,

who knows she’s sufficient,

knows where she’s going

and travels with passion.

Who remembers she’s precious,

but knows she’s not scarce–

who knows she is plenty,

plenty to share.

After the poem, I asked each woman to share something about the woman they are becoming. Some shared that they are becoming more confident, more open, more authentic, and more self-aware. Some are becoming leaders, spiritual guides, teachers, and wise grandmothers.

Several of the women remarked on the line “I am becoming a deep weathered basket.” They resonated with the image – becoming a vessel of whatever they’re called to carry, a little worn, beat up, and perhaps leaking, but still full of gift. The older women on the call focused on the world “weathered”, while one of the younger women said she was grateful for all that leaked out of those weathered baskets into her own, much less seasoned, basket.

When it was my turn to hold the virtual talking piece, my first top-of-mind response was “Satisfied. I am becoming more satisfied.”

I am becoming more satisfied that I am enough. I am becoming more satisfied that I have enough. I am becoming more satisfied that the work that I do is the right work and that I am living as authentically as I can. I am becoming more satisfied that I’m doing the best I can as a mother.

That thought surprised me, given the kind of day and month I’d had, but it popped out of my mouth and after I said it I knew that it was true.

Earlier that day, when one of my daughters had a crisis, I was worried that I hadn’t provided her with enough tools to weather the emotional storms when they come.

Earlier that month, when online sales were flat-lining and a class I was supposed to teach at university got canceled, I was worried that I wasn’t doing a good enough job in growing my business.

And yet, despite those worries, despite the fact that I am still full of human weakness – I still feel the jealousy well up when I see others with more success than me, I still suffer from insecurity when I think I’m not parenting well, I still get unreasonably angry when my husband doesn’t do something I expected him to do – I am becoming more satisfied.

I am not becoming more perfect. I’m not even sure, sometimes, that I’m becoming more wise. My questions increasingly outweigh my answers. But I am becoming more satisfied.

I won’t always parent well. I won’t always say the right things when I teach. I won’t always be successful in my business. My skin is becoming increasingly more saggy and my belly – well, it will never be as flat as I’d like.

BUT I’m learning to love myself more, I’m learning to forgive myself faster, I’m learning to trust that I’ll have the wisdom I need to get through the challenges, and that’s good enough.

With each disappointment, each challenge, each heartbreak, and each victory, I become more authentic, more satisfied, and more committed to being fully myself. As the poem says, I am becoming the woman “who knows she is plenty, plenty to share.”

Now it’s your turn… “Who are you becoming?” Are you satisfied with the answer?

I invite you to join me on a journey that will bring you closer to the woman you are becoming. When you sign up for The Spiral Path, you’ll receive 21 lessons, full of stories, inspiration, journal questions, and embodiment exercises that are designed to bring you closer and closer to the core of who you are. For only $45, you’ll receive a whole lot of content that has the potential to change your life.

Here’s what one participant said before she’d even worked all of the way through: “I’ve worked thru Lesson 9….I have shed tears, felt my anger, and looked at my fears up close and in 3-D. I have felt the darkness, and feel brave and courageous about sitting with it. I now feel much more comfortable in my body and am ready to move ahead and receive all the gifts that will come as a result of this work.” (Carol Brown)

Please join me as we all become the women we’ve wanted.

by Heather Plett | Jan 20, 2015 | Uncategorized

My daughter, Julie, the redhead who’s fierce and fiery and not afraid to challenge me to be a better person, showed me the short story she wrote for her grade 12 English class, and I was so proud of her I asked if I could share it. (She got 99% – missed a couple of typos.)

Killed for Allah, Killed for Honor

Short Story by Julie Laurendeau

I think I’d always felt slightly different. I was never able to put my finger on it, though. Never able to admit to myself why I felt the way I did. I don’t blame myself, however, for my blissful childish ignorance. How could I have known? Never once did I know that what I am was even a remote possibility. There was no such thing as being “different” in my community. I just assumed I was a defect – broken, maybe. That I would grow out of it – see that this was just some silly phase while I grew up. Maybe every girl passes through stages of the same feelings, right? Maybe it was some unspoken universal journey through which every adolescent girl went through, which would make me completely normal. I know now that none of that is true. It all makes a lot more sense now. I am finally able to see the full truth of who I am. I am writing this while I wait here – wait for the unknown. This is my life. I don’t know what’s going to happen to me anymore, and I’m scared… but I know that there are little girls out there who felt the same way I did. So I’m writing this for them. Please, share my story. I know in my heart that this deserves to be told.

I was almost 16 when the fighting got the worst it had been in years. We stayed in our homes most of the time, and just walking in the streets was considered to be a dangerous activity – especially for a young girl like me. The militant men roamed the streets like predators, just looking for reasons to lash out at innocent civilians. Kabul was no longer a place of beauty – it was being slowly destroyed by war. School was no longer considered an option, as desperately as I longed to go. Instead, I sat in my room, watched the far-off fighting through the second-story window and listened to my parents bicker downstairs.

I stop writing. I can hear him behind the door – he’s being loud, as always. I can barely move now, the bruises have gotten so bad. It’s dark in here though, so I can’t really see how badly broken I am, but I can feel the pain like a fire that is swallowing me. I’m getting hungrier by the minute. My mother’s been crying off and on since I’ve been here. I can hear her. Sometimes she sits right by the door, and I’ve heard her been dragged away once by him. I’m so scared. I wish I wasn’t, but I am. I’m trying to be strong, Allah, I really am. Please save me. God, Allah, whoever you are. Save me, save me, save me. I know I must continue to write.

My mother, bless her heart, had been trying desperately to convince my ridiculously patriotic father to move away from the fighting for months. She had her heart set on America, as she’d seen how beautiful and promising it was in all the movies we’d seen while we burrowed in our home. My father, however, was the 10th generation in his family to be born and raised in Kabul, so he wanted to ride out the war. He was hardheaded and stubborn, to say the least. And traditional. Yes, he was a stickler for old-time tradition. My mother, a tiny feisty little dark-haired woman, was less so, but she was never really given the chance to voice her opinions. I had always had a rocky relationship with my father, but day-by-day things seemed to get worse. I was the only child and I knew he had desperately hoped I would be a boy. I loved him dearly- because he was my blood, but I feared him terribly.

I pause for a second since the pain has gotten so bad. I’m weak. I haven’t eaten for around two days. I don’t really know how long exactly, since it’s dark here and I have no way of telling. How could you do this to me, Allah? I’ve been praying for days, but you’ve stopped answering. Have I sinned that badly? Is what I’ve done really that bad? I think I’m dying now. Forgive me, please forgive me, Allah. I must continue to write.

My father finally agreed to move the same day I turned 16. After much discussion and bartering, he consented to my mother’s dream of leaving for America. About a year ago his brother had moved there as well, so we had planned to meet up with them. I was conflicted on how I felt towards our upcoming relocation. I was scared, if I’m being honest. Kabul, and that small little home right on the outskirts, was all I’d ever known. I knew my English was decent, and much better than both my parents’, but I had no idea how to live in their way. All I’d ever seen of America was what was shown in movies, and I had a feeling that my experience wasn’t going to be like what I’d seen in “Sex and the City.” At least I hoped not. I was excited, however, for the change in scenery. I needed somewhere that I could stretch my legs and get away from the militant, strict, lifestyle I had now. I needed a break from tradition – I thought maybe America would be good for me in that way. I knew it was nothing like the life I’d lived before, but maybe that was a good thing! I always had felt like a bit of a fish out of water in my own family and in this culture, even. I had never thought I was cut out for the typical life of an Afghani woman, so maybe this was the opportunity I needed to save myself from that. I knew 16 was considered prime marrying age, but nothing had ever scared me as badly as the thought of marriage. I had spent whole nights crying myself to sleep after my father brought up the idea of possible suitors. I think I knew, even back then, that that life would never be for me.

My body has forced me to stop for a minute. It’s getting hard to breathe. I think I’m either going to die here, or he’s going to kill me. I’m not sure what I’d prefer, at this point. Whatever is quicker, I think. I’m ready to go. All this silence and loneliness has forced me to come to terms with myself and with my God. I no longer know if you exist. I know that’s a sin, to even think that, but I’m past the point of caring. You’ve abandoned me here. There may be no afterlife for me to look forward to, but anything would be better than this. I am ready to die, but I must continue to write.

I won’t bore whoever finds this with the details of the preparations for our move or our long journey. It was tedious, and seemed to take forever, but by June – 4 months after my birthday – we landed in a place called Seattle. That is where my uncle had moved his family, so that was where we went. My uncle scared me a little as well, and so did his two sons. They were tall, lanky, boys who were raised in the traditional Afghani way to believe that they deserved whatever they wanted. I had always been afraid as a kid that I would be forced to marry one of my cousins, but my mother disliked them too much to allow that to happen. I hated my father even more when he was around his brother. He became scarier, and more power-hungry.

I hear noises, so I pause. The younger one taunts me from behind the door. I guess they’ve come to join him in torturing me. “You chose this, Adeela! You brought this on yourself. You’re a freak, unnatural. Allah hates you.” I hear him spit on the door in disgust. Please, Allah, even if you hate me – just take me from this life. I am broken, but I must continue to write.

I’ll cut to the chase and get to the real story. The day I started school in America was the scariest day of my young life. I was excited though, to finally get to go back to school, but I had no idea what to expect. Luckily, we came right around the start of the “second term” so I would be able to start completely new classes. The first class I had in the morning was English Language Arts, so naturally I was terrified. I knew I was considered an able writer back home, but this was different. The class stared as I walked in, but that was to be expected. As much as I felt like a fish out of water back home, here I was a total outsider. I moved quietly to the back as my new teacher introduced me to the rest of the class. I picked an open seat next to a girl with the ends of her hair dyed blue. She smiled at me as I put my notebook down on the table, and I’ll never forget how I felt in that moment. That was the first time I’d ever gotten butterflies.

My stomach feels like it’s caving in on itself. I get nearer to death every second. I’ve stopped crying. There’s no use. No one’s listening. I can feel the words pouring out of my chest, so I must continue to write.

She’d introduced herself as Charlotte. “But everyone calls me Charlie. I think it suits me better,” she’d told me with a tinkling laugh. She asked for my name and I told her it was Adeela. She had trouble pronouncing it at first, but after the third try she got it right. I remember how much I’d admired her for trying. Twice that day I’d already heard the phrase “Can I just call you Adele?” and I hated it. Charlie asked to see my schedule to see if we had any other classes together, and my heart skipped a beat when she said she’d show me to my next period Biology even if it was a little out of her way. Charlie and I spent the rest of the period whispering and laughing to ourselves in the back of the class. I remember vividly how much I liked it. I also remember how guilty it made me feel.

I hear the doorbell ring twice, but no one answers. I think to myself that maybe it’s Charlie, and my heart feels as heavy as an anchor. I can’t believe I’ll never even be able to tell her goodbye. The pain is getting worse again, but I’ve stopped being able to cry at all. All there is to do is wait. If you’re out there, God, please just pity me. I am sorry for what I’ve done. I need to keep writing.

After English Charlie fulfilled her promise to walk me to biology. As we navigated the halls, she introduced me to her friends and showed me places I should know. I could tell that she was liked by many, which made it feel even more special to be in her presence. I couldn’t help but stare at her in awe as I followed behind her quick steps. She paused outside the door to my Biology class and wished me luck. She told me she’d save me a spot at her table at lunch – no words had ever sounded as sweet. I spent all of Biology and 3rd period Math waiting for the lunch bell to ring. Charlie had done this to me. I was utterly confused about this feeling that sat in my stomach, but I never wanted it to end. The afternoon passed by in a blur.

My hands have gotten shaky. Can you hear me, Allah? All my life I’ve thought you were listening every time I bowed and prayed to you, but I doubt that now in what I expect will be my final days. You have left me here. You have left me here to die. What kind of God would do that to his daughter? I must continue to write.

The entire night after that first day was spent with Charlie in my mind and a pit in my stomach. I was terrified to even look at my father – I thought he’d see things in my eyes that would give me away. I still didn’t know at that point what I was feeling, but I knew it wasn’t right. Still, I couldn’t wait to see her again in the morning. Each of my dreams that night were tinged with blue and all involved girls named Charlie…

I hear yelling outside the door. It doesn’t faze me anymore. I will sit here and wait for Death to come for me. I will embrace him when he comes. I must continue to write.

The next day passed by relatively the same way as the day before. Charlie and I talked and laughed in English class, she walked me to Biology, and saved me a seat at lunch. My heart fluttered the exact same way every time she tossed her mid-length hair over her shoulder and laughed. I was standing at my new locker at the end of the day when the real excitement happened. My heart stopped when Charlie asked if I wanted her to come over and have her tutor me for biology. She said we couldn’t go to her house because her mother ran a daycare, so I agreed to go to mine because it meant I got to spend more time with her.

For the first time in hours, I begin to cry again. My chest unleashes sobs which feel like floods. Please don’t let me die here. I take it all back. I do not want to die. I must continue to write.

As we walked to my house, Charlie told me about her life. I listened intently. I loved the way her voice sounded and I adored her silly little laugh. She spoke of her two little sisters and how she’d grown up in Chicago. She told me of the summers of her childhood spent in a little beach house off the Eastern coast, and all the movies she loved. There was a magic about her – an undeniable beauty about how she was unabashedly herself. No one was home when we arrived at my new little house tow streets past school, so I showed her around before we decided to go to my room. Charlie flopped right onto the bed when we walked in, and immediately announced that she was going to have to do something about the plain walls. She told me it didn’t represent my beauty well enough, and I thought my heart would explode.

The tears will not stop coming now. Kill me Allah, kill me. I have been your faithful servant all these years. I prayed to you 8 times a day and never said a bad word about anyone. Please, if there’s one thing you can do for me after all this time – just kill me. I refuse to die at his hand. I fear that I will not have much more time, so I must continue to write.

After only a half hour of studying, I could tell that Charlie’s mind was somewhere else. Even after only knowing her for two days, I felt like I had developed an ability to tell when something was wrong with her. She also wasn’t very good at hiding her feelings. After a couple minutes of visible anxiety, Charlie threw her book down.

“So were you ever planning on telling me how you feel? I can see the way you look at me, Adeela. Don’t think I haven’t noticed,” she said with a sly smile from underneath her hair.

My heart stopped beating, and I felt my stomach drop to the floor. I was mortified. But then she continued.

“You do know I’m gay too, right?” She said, looking me fully in the eyes now.

I felt my entire heart stop when she uttered that sinful sentence. I hadn’t even been able to think the word to myself, let alone say it aloud. I had heard of others who’d been… gay, but they were shunned forever or changed themselves back into being normal again. Never had I once thought of myself as… one of then. Sure, these feelings were… confusing, but surely they weren’t this. Surely this was nothing but confusion, right? Surely I’d grow out of it? And then suddenly, Charlie had made up the two feet of space between us and was kissing me, and everything, all at once, seemed to change.

I can hear him outside the door, loading bullets into his gun. He’s playing music, as if this was a normal day to him. He’s singing along. Show me strength, Allah. My hands are getting weaker and my eyes are going dry, but I must continue to write. Not much time left.

I had never tasted anything as sweet as Charlie’s lips on mine. She pulled away way too quickly, just to gauge my reaction. I can’t even imagine the look she must have seen on my face, but she didn’t see it for long since I kissed her again after just a second. Our lips moved in synchronization for a few minutes while the butterflies in my stomach went crazy. My bedroom door opened then, and all of my worst nightmares seemed to come true simultaneously. There stood my father, still in his work clothes, with the most terrifying look I’ve ever seen on his face.

My final moments on Earth are being spent in a dark basement in a city I barely know in a country I never got to see. Do I deserve this? I may never know the answer to any of the questions that fill my mind, but at least I can share my story. I must continue to write.

After a minute of pure shock he started screaming in Arabic. The only words he got out in English were two words shrouded in disgust hurled across the room at my beautiful Charlie. “Get out.” I knew my father, so I could tell that surely a violent outburst would follow his verbal rage. Charlie looked at me like she would do whatever it took to save me, but I whispered at her to just leave. She mouthed goodbye to me and ran down the stairs, books in hand. My father picked up a lamp and aimed at my head. I took one final glance at Charlie’s fleeting figure.

I’m so weak now. I long for peace. I know now that it will only be brought in death. I believe that Allah will accept me in his kingdom. At least My Allah will. No god I believe in would turn away his daughter. I must continue to write.

“What is wrong with you, Adeela?” hissed my father in my direction. “You have invited the devil into your body… Allah does not approve of your choices you stupid cow!”

I could feel my heart break. I’d known it all along, hadn’t I? I was always just too afraid, too ashamed to admit it to myself let alone anyone else. This is why the life of an Afghani woman had never appealed to me – because the thought of a man had never appealed to me either. I’m gay. My name is Adeela Ahmadi, and I am gay. While I came to that realization, something inside of my father snapped.

Death will not have to wait much longer. I must continue to write.

“You deserve to die for the shame you have brought on this family, Adeela!” he yelled. My name had never sounded like an insult until that very moment. He grabbed me by the wrist and pulled me down the stairs with him until we were on the main floor. I think I was probably crying out for help, but it all seems to be a bit of a blur. I do remember vividly however, the look on my mother’s face as she walked in the door from doing her errands. She ran to my side and did her best to get him to let go, but it was no use. He had never listened to her before. My father threw me down the basement stairs. He shut off the lights and whispered once more “You deserve to die.” I heard the door lock.

Please, just let this all be quick. I continue to write.

I have been here for nearly three days, I believe. Time has stopped having a meaning. I can’t sleep any longer, and my lungs are struggling to fill. I know not whether what I have done is a sin, but I am prepared to die now. I do not regret my choices. This is who I am. I can hear him unlocking the door. My mother is shrieking in her native tongue, trying desperately to stop him from doing what he’s about to do. I love my mother. She was never made for this life either. I can hear them struggle for a minute or two, and then she falls silent. I can see a crack of light as he pries the door open. There is nothing more to write. I am about to die.

He walks down the stairs, slowly, all the while hissing prayers at me. He stops when he gets to the bottom where I am laying. He kneels. I can feel the cold barrel of the gun pressed to my temple. I am no longer afraid. Allah is here with me. I decide to do the only thing I’ve ever known. I close my eyes, and I begin to pray.

Praise is only for Allah, Lord of the Universe.

The most Kind, the most Merciful.

The master of the Day of Judgement.

You alone we worship and to you alone we pray for help.

Show us the straight way,

The way of those whom you have blessed.

Who have not deserved your anger,

Nor gone astray.

Take me home.

A few nights ago, I was reading in bed when my husband turned to me and said “It must be a good book. You haven’t taken your nose out of it all evening.” He was right – it IS a good book. It’s called Pilgrimage of Desire: An Explorer’s Journey Through the Labyrinths of Life by Alison Gresik. Reading it was like getting cozy in front of the fire with a glass of wine and an old friend who knows your thoughts before you even speak them. Let’s just say Alison and I have a LOT in common.

A few nights ago, I was reading in bed when my husband turned to me and said “It must be a good book. You haven’t taken your nose out of it all evening.” He was right – it IS a good book. It’s called Pilgrimage of Desire: An Explorer’s Journey Through the Labyrinths of Life by Alison Gresik. Reading it was like getting cozy in front of the fire with a glass of wine and an old friend who knows your thoughts before you even speak them. Let’s just say Alison and I have a LOT in common. I think that desire is what moves us through the labyrinth. There must be something that compels us, draws us forward or pushes us on, and I believe that is desire, a deep urge to go from one place to another. If we don’t want something — if our heart doesn’t want to beat, if our lungs don’t want air — then we’re not alive. And the labyrinth channels and directs that movement, that desire, in its mysterious unfolding path.

I think that desire is what moves us through the labyrinth. There must be something that compels us, draws us forward or pushes us on, and I believe that is desire, a deep urge to go from one place to another. If we don’t want something — if our heart doesn’t want to beat, if our lungs don’t want air — then we’re not alive. And the labyrinth channels and directs that movement, that desire, in its mysterious unfolding path.