by Heather Plett | Jun 24, 2015 | art of hosting, circle

“The art of conversation is the art of hearing as well as of being heard.” ― William Hazlitt

The wedding I officiated on the weekend took place in a circle. The bride and groom and I stood in the centre, with the guests gathered around us.

After I had shared a few words of wisdom about marriage, I read a blessing and then passed a talking piece (a stone on which I’d printed their names) around the circle inviting each person to speak their own one-sentence blessing to the couple. If they didn’t feel comfortable speaking, they had the option to simply hold the stone for a moment and offer an unspoken blessing.

It was a beautiful and simple ritual that felt like the couple was being held in a giant container of love by their community.

As I said in this piece last November, the talking piece isn’t magic, but “what IS magic is the way that it invites us to listen in ways we don’t normally listen and speak in ways we don’t normally speak.”

When a talking piece goes around the circle, the person who holds it is invited to “speak with intention”. Everyone else is invited to “listen with attention” and not interrupt or ask questions. Everyone in the conversation is invited to “tend the well-being of the circle”. (Those are the three practices of The Circle Way.)

A talking piece conversation has a unique quality to it. There is more listening, less interrupting,  more pausing, and, almost always, more vulnerability than ordinary conversations. Yes, some people get nervous about the talking piece (because it puts them on the spot and feels like pressure to say something important), but when they get used to it, (and when they realize that anyone is welcome to pass the talking piece without speaking) almost everyone acknowledges that the talking piece brought something special into the space that they’ve rarely experienced before.

more pausing, and, almost always, more vulnerability than ordinary conversations. Yes, some people get nervous about the talking piece (because it puts them on the spot and feels like pressure to say something important), but when they get used to it, (and when they realize that anyone is welcome to pass the talking piece without speaking) almost everyone acknowledges that the talking piece brought something special into the space that they’ve rarely experienced before.

The talking piece is not meant for every conversation, but I believe it should play a more significant role in many of our conversations. Here’s why:

1. The talking piece invites us to listen much more than we talk. When in a circle with a dozen people, I have to listen twelve times as much as I talk. That’s a very good practice. Listening opens our hearts to other people’s stories. It invites our over-active minds and mouths to pause and be present for people who need to be witnessed. And when it’s our turn to talk, we know that we are being listened to just as intently.

2. The talking piece encourages us to get out of “fix-it” mode. When a friend shares a problem with us, it usually feels more comfortable to jump in with a solution than to sit and really listen. But unless that friend has asked for advice, what she/he probably needs more than anything is a listening ear. The talking piece doesn’t allow us to interrupt with our version of “the truth”. Often, simply because they’ve been heard in a deeper way than they’re used to, people walk away from the circle having figured out their OWN solutions for their problems.

3. The talking piece makes every voice equal. Nobody has the podium in a circle. Nobody stands on a stage. Each voice makes a valuable contribution to the conversation and none is more important than the others. With so many race issues happening recently (especially in the U.S. and Canada), I like to imagine what might happen if more people were to sit in circle with people of different races. What if we mandated interracial circle conversations for every high school student? What if students couldn’t graduate unless they’d spent time learning to listen to stories told by people who are different from them? What if Dylan Roof, for example, had sat in a weekly circle listening to stories from the black community? Might that have changed last week’s outcome?

4. The talking piece invites us more physically into the conversation. There’s something special about holding an object in your hand that has been passed there from hand to hand around the circle. It invites us to be present in not just our heads but in our bodies. It invites us to sink physically into the conversation, engaging in a deeper way because our hands are engaged along with our hearts.

5. The talking pieces creates the silence into which open hearts dare to speak. There’s a level of vulnerability that shows up in the circle that is rarely present in other conversations. Because the talking piece invites us to slow down and be more intentional, we don’t just talk about the weather or yesterday’s shopping trip. We talk about things that are real and we show up authentically for each other.

Have you had experience with a talking piece? I’d love to hear about it.

If you haven’t experienced it yet, don’t be afraid to try. Yes, you might get some funny looks from your family or friends when you pull out a stone, a stick, or even a pen and invite them to pass it around the circle, but there’s a very good chance – if they’re openhearted and authentic – that they will be surprised at what it brings to the conversation.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | May 15, 2015 | circle, Community

All week, I’ve been trying to write a piece about The Circle Way, but nearly every effort ends on the virtual cutting room floor.

How do you write about something that has radically altered the course of your life, that has changed nearly every relationship in your life, and that has brought you into the most authentic conversations you’ve ever experienced? How do you do justice to the kind of wisdom that is as ancient as humankind and still as fresh as the lilac buds bursting open in the Spring sun?

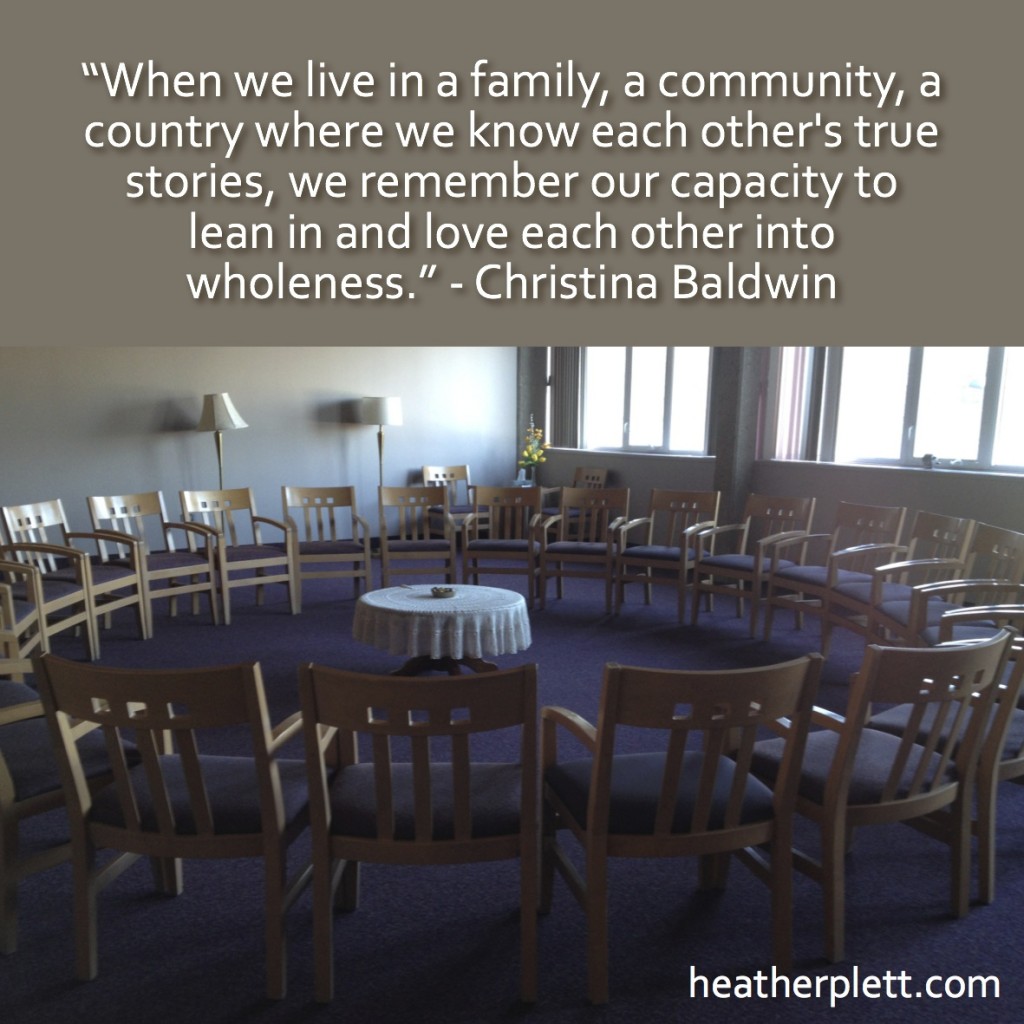

Next week I will have the privilege of being in circle with my friends and mentors, Christina Baldwin and Ann Linnea. The anticipation of that has me reflecting on the significance of circle in my life and I want to share some of those thoughts with you. I will try, despite my inability to write it as eloquently as I’d like…

Nearly fifteen years ago, I discovered Christina’s work and knew instantly that it would change my life. I was in a particularly hungry place in my life at the time, working in a toxic bureaucratic environment that was making me realize just how much I craved real connection in my work and life. I’d sat in too many leadership meetings where every word spoken came from a guarded place and I longed for authenticity. I devoured Calling the Circle: The First and Future Culture, and, though I didn’t entirely understand the circle or see clearly how I could adopt it into my life yet, I knew this was something I wanted with every fibre of my being.

I knew that the circle was the doorway into the authentic way I longed to live my life.

Sitting in my government office one day after reading her book, I promised myself that I would study with Christina some day. Ten years later, that intention was realized and I sat in circle with her, devouring everything she had to teach me. Now, five years later, circle has become embedded into all of my work and I have become part of the global network of circle hosts and teachers who will continue to spread circle practice as Christina and Ann transition into their roles as elders of the lineage. Be careful what you wish for!

In case you are curious about circle but (like me fifteen years ago) don’t fully understand how it can change things, here are two recent ways that I’ve used circle practice…

1. Circle in the classroom

When my students were in conflict about a group project a few weeks ago, I invited them to push the tables against the wall and move their chairs into circle. With a few simple guidelines, I taught them how to have conversation in circle, looking into each other’s eyes, remaining silent when someone else was holding the talking piece, and being as honest as they were comfortable being when it was their turn to talk. People opened up in ways they don’t normally in the classroom, we addressed the source of the conflict, and we were able to move in a new direction. The students were surprised the following week when, after a second circle session, I let them abandon the group project entirely, but I told them to see it as a learning opportunity rather than a failure. In the final round with the talking piece, we each shared something we’d learned from the process. Everyone walked away looking a little lighter than when we’d started because they’d been heard by each other and by me.

2. Weekly women’s circle

Ever since I joined Gather the Women four years ago, I’ve wanted to start a women’s circle, but until recently, the timing wasn’t quite right. Finally in January, I knew it was time. I sent out an invitation and around 15 women accepted the invitation. Since then, we have been meeting on a weekly basis and, though it’s not the same women each time (everyone is welcome), we always have deep and authentic conversations. The circle offers us something we are all hungry for – a place to share our personal stories, to peel away our masks, to be honest about our shame and fear, and to heal. With the help of a talking piece, we are each given the opportunity to share stories without interruption or advice. We come to the circle not to fix each other but to listen and be listened to.

Each circle has different energy and holds a different purpose, but there are some things that every circle I host or participate in have in common. Here are just a few of them:

1. Being intentional about the space changes the way the conversation unfolds. Have you ever sat in an office talking to a senior manager who stayed behind their desk the whole time? Consider how you felt during that interaction. Though it may have been subtle, the desk separated you, gave the other person the position of power, and probably kept you from being authentic or vulnerable. In the circle, we sit and look into each other’s eyes without barriers between us and without anyone sitting in a position of power and it changes the way we interact with and are present for each other.

2. Simple rituals (sitting in circle, placing something meaningful in the centre, using a talking piece, etc.) shift us out of our everyday, often mindless conversations into something that is more mindful and deep. I’ve seen this happen especially in university classrooms where I invite students away from the tables placed in rows (where some have their backs to others) and into a circle where they face each other. Instantly they are more present, less easily distracted, and more willing to open up to each other.

3. The talking piece invites us to listen more than we speak. When you are holding the talking piece, your story holds the place of honour. When someone else holds it, their story is the honoured one. This gives you both an opportunity to speak intentionally without interruption or advice and to listen with attention without needing to interject your own story or solutions into someone else’s story. In far too many of our conversations, we feel the need to fix people, critique them, or give them good advice, which often makes that person feel like they’re flawed or not as smart as you. In truth, the gift of being listened to is often more healing than any advice you could give.

4. The circle offers us an opportunity to share the burden of the stories we carry. During our Thursday evening women’s circle, a lot of intense, personal stories come up – stories of depression, abuse, grief, etc.. These are the kinds of stories that feel really heavy to hold if you’re trying to carry them alone, or if it’s just one friend is helping to hold them for another. When they’re shared into the container of the circle, however, nobody leaves the room carrying the story alone and nobody feels solely responsible for helping another carry them. In the process of sharing them, we begin to heal each other. As one of the women shared in the circle, we do not only have “a leader in every chair”, we have “a healer in every chair”.

5. People need to come to the circle when they’re ready for it. The intensity of the circle is too much for some people and they need to walk away. That’s okay. We have to trust them to know when they’re ready to be held in that way. When they walk away, I simply wish them a blessing and hope some day when they’re ready for it, they’ll find the right circle. I would rather wait for them to be ready then to try to impose something on them that feels unsafe at the time.

6. Circle is not always be easy. I have been in many incredible circles and they are always meaningful experiences, but sometimes they’re hard. Sometimes things come to the surface that people have kept hidden for a long time and that surfacing can be painful for the person sharing and/or wounding for the people listening. The circle can hold all of that, but only if it’s guarded well and only if the people involved take responsibility for “holding the rim” and staying with the process until something new begins to grow into the cracks that have formed.

There is much more to be said about circle than this post can hold. And there are also things that cannot be articulated and can only be experienced. I encourage you to find a way to experience it. In the future, I will be offering circle workshops, but in the meantime, I encourage you read The Circle Way and to check out what my mentors at PeerSpirit have to offer. If you are a woman, I also encourage you to consider joining Gather the Women and perhaps finding or starting a circle where you live. If you are in Winnipeg, you’re welcome to join our Thursday evening circle.

If you have questions you’d like me to address in future articles, either about The Circle Way or about other topics I write about, please feel free to ask (by comment or email). Even if I don’t get back to you right away, please know that I appreciate every piece of correspondence I receive. Once a month, I plan to write an article specifically addressing a question I receive.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Mar 4, 2015 | art of hosting, circle, Uncategorized

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

If you want to make a tasty soup, you don’t throw your ingredients onto the stove and hope they somehow transform themselves into a soup.

Instead, you choose the right container that will hold all of the ingredients and allow room for the soup to boil without bubbling over onto the stove. Then you begin to add the ingredients in the right order. First you might fry onions and garlic to bring out their best flavour. Then you add the right amount of soup stock. And finally the vegetables and/or meat are added according to how long each ingredient takes to cook. If you want to make a creamy or cheesy soup, you add the dairy only after everything else has cooked and the soup is no longer at a full boil.

Through this intentional and careful act of creation, you allow the flavours to blend and layer into a meal that has the potential to be greater than the sum of its parts.

The same is true for a meaningful conversation.

If you want to gather people to talk about something important, you don’t simply throw them together and hope what shows up is good and meaningful. Sure, sometimes serendipity happens and a magical conversation unfolds in the most unexpected and unplanned places, but more often than not, it requires some intention to take the conversation to a deeper, more meaningful level.

Take, for example, the recent community conversation on race relations that Rosanna Deerchild initiated and I facilitated. If we had simply invited people into a common space for a meal without giving some thought to how the conversation would flow, people would have stayed at the tables where their friends or family had gathered, conversations would have stayed at a fairly shallow level, and we wouldn’t have gotten very far in imagining a city free of racism. Instead, we moved people around the room, mixed them with people they’d never spoken with before, and then asked a series of questions that encouraged storytelling and the generation of ideas. Through a process called World Cafe, we arranged it so that everyone in the room would end up in small, intimate conversations with three different groups of people. We followed that up with a closing circle. (Stay tuned for more idea-generating conversations such as this one in the future.)

Especially when the subject matter is as challenging as race relations, the quality of the conversation is only as good as the container that holds it.

If you try to cook soup in a plastic bowl, you’ll end up with a melted bowl and a mess all over your kitchen. Similarly, if you try to have a heated conversation in a container not designed for that purpose, you run the risk of doing more harm than good.

The same is true for our Thursday evening women’s circle. We could have a perfectly lovely time gathering informally to talk about our families, our jobs, and our latest shopping trips, but if we want to have the kind of intimate, open-hearted conversations we always have, we have to create the right container that can hold that level of depth. In this case, the container is the circle, where we pass a talking piece and listen deeply to each person’s stories without interrupting or redirecting the conversation.

Recently, a few people have asked whether the principles that I teach (that emerge out of The Circle Way and The Art of Hosting) might be transferable to other, less formal conversations. What if I have to have a difficult conversation with my parents or siblings, for example? Or with my co-workers? Or my kids? What can I do to make sure everyone is heard in an environment where I’m certain they’d all laugh at the idea of a talking piece?

In many of our day-to-day conversations, it may not be practical or even desirable to set the chairs in a circle or bring in a facilitator to help you navigate difficult terrain. But that doesn’t mean you can’t be intentional about creating the right container for your conversations.

Here are some tips for creating containers for meaningful everyday conversations:

1. Consider the way the physical environment fits the conversation. If you want to have a potentially contentious conversation with your staff, for example, you might find that a meeting space away from your office provides a more neutral environment. If you want to talk to a friend about something that will invite vulnerability and deep emotion, you might not want to do it in a coffee shop where you run the risk of overexposure. Or if you need to talk to your parents about their declining health, it’s probably best to do that in an environment that feels safe for them.

2. Find ways to make the physical environment more conducive for intimate and intentional conversation. If you wish to invoke the essence of circle, for example, you could place a candle on the table between you. Or move the table out of the way entirely to remove the boundaries. If you want to invite creative thinking into the room, set out blank paper and coloured markers for doodling. (This would be a great way of planning your vacation with your family, for example.) Consider how the space can help you create conditions for success. Even if you are meeting online, you can still evoke safe physical space by inviting participants to imagine the common elements they would place in a room if they were all together.

3. Host yourself first. If you know that a conversation will be difficult for you and/or anyone else involved, be intentional about preparing for it well. Take some time for self-care and personal reflection. Go for a walk, write in your journal, meditate, or have a hot bath. You’ll be much more prepared to bring your best to a conversation if you enter it feeling relaxed and strong. If you plan to ask some hard questions in the conversation that might trigger others in the room, ask yourself those questions first and write whatever comes up for you in your journal. Don’t ask of anyone else what you’re not prepared to first ask of yourself.

4. Ask generative questions. Questions have the power to shut down the conversation if they come across as judgmental or closed-minded, or they have the power to help people dive more deeply into their stories and imagine a new reality together. Consider how your questions make the people you’re in conversation with feel heard and respected, and consider how a question might invite everyone present to generate fresh perspectives and deeper relationships.

5. Model vulnerability and authenticity. In order to engage in deep and meaningful relationships, participants need to be willing to be vulnerable and authentic. If you want to invite others into that space of openness and vulnerability, you need to be prepared to go there yourself. Consider starting the conversation with a personal story that will invite similar storytelling from others. Storytelling opens hearts and brings down defenses, and that’s the place where meaningful conversation thrives.

6. Listen well. People are much more inclined to engage when they feel that they are seen and heard and not judged or marginalized. Practice deep listening. As Otto Scharmer and Katrin Kaufer teach in Leading from the Emerging Future, we need to move beyond level 1 (downloading) and level 2 (factual) listening to level 3 (empathic) and level 4 (generative) listening. Empathic listening is about being willing to enter into someone else’s story and be impacted and changed by it. Generative listening is about being fully present in your listening in a way that can generate something new and fresh out of that shared space. If you model effective listening, it will be much easier for others to follow your example. Even if you don’t use a talking piece, imagine that the person you’re listening to is holding a talking piece and give them undivided attention. When they are fully heard, they will be more likely to do the same for you.

7. Guard the space and time carefully. When we gather in The Circle Way, one person serves as the guardian, paying attention to the energy of the room and bringing the conversation back to intention when it wanders off. This person takes responsibility for ensuring that the space is protected, not allowing interruptions or distractions. When you are in a conversation that is important to you, consider how you can guard the space. Eliminate distractions like cell phones or other electronics. Consider what needs attention in order to make everyone feel safe and protected. When vulnerability is called for, for example, take care to create an environment where nobody is allowed to interrupt the storytelling.

8. Co-create future possibilities. If you enter a conversation convinced that you know how it’s supposed to turn out, you will limit what can happen in that conversation. Those you’ve invited into the conversation will sense that their participation is not fully valued and will shut down and not offer their best. Instead, enter a conversation with an open heart, an open mind, and an open will and be prepared to emerge with a new possibility you’ve never considered before. Allow the stories and ideas generated in the conversation to change the future and to change you.

When you begin to pay more attention to the container in which you hold your conversations, you’ll be surprised at how much more depth and meaning will emerge. Sometimes, this will mean difficult things will surface and it won’t always be comfortable, but with the right care and attention, even the difficult things will help you move in a positive direction.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Feb 18, 2015 | circle, Community, Leadership, Uncategorized

“The moment we commit ourselves to going on this journey, we start to encounter our three principal enemies: the voice of doubt and judgment (shutting down the open mind), the voice of cynicism (shutting down the open heart), and the voice of fear (shutting down the open will).” – Otto Sharmer

Lessons in colonialism and cultural relations

Recently I had the opportunity to facilitate a retreat for the staff and board members of a local non-profit. At the retreat, we played a game called Barnga, an inter-cultural learning game that gives people the opportunity to experience a little of what it feels like to be a “stranger in a strange land”.

To play Barnga, people sit at tables of four. Each table is given a simple set of rules and a deck of cards. After reading the rules, they begin to play a couple of practice rounds. Once they’re comfortable with the rules of play, they are instructed to play the rest of the game in silence.

After 15 or 20 minutes of playing in silence, the person who won the most tricks at each table is invited to move to another table. The person who won the least tricks moves to the table in the opposite direction. All of the rules sheets are removed from the tables.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

Newcomers (ie. immigrants) have now arrived in a place where they expect the rules to be the same, find out after making a few mistakes that they are in fact different, and have no shared language to figure out what they’re doing wrong. Around the room you can see the confusion and frustration begin to grow as people try to adapt to the new rules, and those at the table try to use hand gestures and other creative means to let them know what they’re doing wrong.

After another 15 or 20 minutes, the winners and losers move to new tables and the game begins again. This time, people are less surprised to find out there are different rules and more prepared to adapt and/or help newcomers adapt.

After playing for about 45 minutes, we gathered in a sharing circle to debrief about how the experience had been for people. Some shared how, even though they stayed at the table where the rules hadn’t changed, they began to doubt themselves when others insisted on playing with different rules. Some even chose to give up their own rules entirely, even though they hadn’t moved.

In the group of 20 people, there was one white male and 19 women of mixed races. What was revealing for all of us was what that male was brave enough to admit.

“I just realized what I’ve done,” he said. “I was so confident that I knew the rules of the game and that others didn’t that I took my own rules with me wherever I went and I enforced them regardless of how other people were playing.”

It should be stated that this man is a stay-at-home dad who volunteers his time on the board of a family resource centre. He is by no means the stereotypical, aggressive white male you might assume him to be. He is gracious and kind-hearted, and I applaud him for recognizing what he’d done.

What is equally interesting is that all of the women at the tables he moved to allowed him to enforce his set of rules. Whether they doubted themselves enough to not trust their own memory of the rules, or were peacekeepers who decided it was easier to adapt to someone else who felt stronger about the “right” way to do things, each of them acquiesced.

Without any ill intent on his part, this man inadvertently became the colonizer at each table he moved to. And without recognizing they were doing so, the women at those tables inadvertently allowed themselves to be colonized.

If we had played the game much longer, there may have been a growing realization among the women what was happening, and there might have even been a revolt. On the other hand, he might have simply been allowed to maintain his privilege and move around the room without being challenged.

Making the learning personal

Since that game at last week’s retreat, the universe has found multiple opportunities to reinforce this learning for me. I have been reminded more than once that, despite my best efforts not to do so, I, too, sometimes carry my rules with me and expect others to adapt.

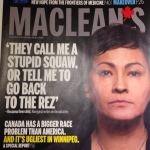

Yesterday, these lessons came from multiple directions. In one case, I was challenged to consider the language I used in the blog post I shared yesterday. In writing about the race relations conversation I helped Rosanna Deerchild to host on Monday night, I mentioned that “we all felt like we’d been punched in the gut” when our city was labeled the “most racist in Canada”. Several people pointed out (and not all kindly) that I was making an assumption that my response to the article was an accurate depiction of how everyone felt. By doing so, I was carrying my rules with me and overlooking the feelings of the very people the article was about.

Not everyone felt like they’d been punched in the gut. Instead, many felt a sense of relief that these stories were finally coming out.

In the critique of my blog post, one person said that my comment about feeling punched in the gut made her feel punched in the gut. Another reflected that mine was a “settler’s narrative”. A third said that I was using “the same sensationalist BS as the Macleans article”.

I was mortified. In my best efforts to enter this conversation with humility and grace, I had inadvertently done the opposite of what I’d intended. Like the man in the Barnga game, I assumed that everyone was playing by the same set of rules.

I quickly edited my blog post to reflect the challenges I’d received, but the problem intensified when I realized that the Macleans journalist who wrote the original article (and who’d flown in for Monday’s gathering) was going to use that exact quote in a follow-up piece in this week’s magazine. Now not only was I opening myself to scrutiny on my blog, I could expect even harsher critique on a national scope.

I quickly sent her a note asking that she adjust the quote. She was on a flight home and by the time she landed, the article was on its way to print. I felt suddenly panicky and deeply ashamed. Fortunately, she was gracious enough to jump into action and she managed to get her editor to adjust the copy before it went to print.

Surviving a shame shitstorm

Last night, I went to bed feeling discouraged and defeated. On top of this challenge, I’d also received another fairly lengthy email about how I’ve let some people down in an entirely different circle, and I was feeling like all of my efforts were resulting in failure.

At 2 a.m., I woke in the middle of what Brene Brown calls a “shame shitstorm”. My mind was reeling with all of my failures. Despite my best efforts to create spaces for safe and authentic conversation, I was inadvertently stepping on toes and enforcing my own rules of engagement.

As one does in the middle of the night, I started second-guessing everything, especially what I’d done at the gathering on Monday night. Was I too bossy when I hosted the gathering? Did I claim space that wasn’t mine to claim? Were my efforts to help really micro-aggressions toward the very people I was trying to build bridges with? Should I just shut up and step out of the conversation?

By 3 a.m., I was ready to yank my blog post off the internet, step away into the shadows, and never again enter into these difficult conversations.

By 4 a.m., I’d managed to talk myself down off the ledge, opened myself to what I needed to learn from these challenges, and was ready to “step back into the arena”.

Some time after 4, I managed to fall back to sleep.

Moving on from here

This morning, in the light of a new day, I recognize this for what it is – an invitation for me to address my own shadow and deepen my own learning of how I carry my own rules with me.

If I am not willing to address the colonizer in me, how can I expect to host spaces where I invite others to do so?

Nobody said this would be easy. There will be more sleepless nights, more shame shitstorms, and more days when my best efforts are met with critique and even anger.

But, as I said in the closing circle on Monday night, I’m going to continue to live with an open heart, even when I don’t know the next right thing to do, and even when I’m criticized for my best efforts.

Because if I’m not willing to change, I have no right to expect others to do so.

by Heather Plett | Feb 17, 2015 | circle, Community, connection, courage, Leadership, Uncategorized

What do you do when your city has been named the “most racist in Canada“?

Some people get defensive, pick holes in the article, and do everything to prove that the label is wrong.

Some people ignore it and go on living the same way they always have.

And some people say “This is not right. What can we do about it?”

When that story came out, some of us felt like we’d been punched in the gut. Though it’s no surprise to most of us that there’s racism here, this showed an even darker side to our city than many of us (especially those who, like me, sometimes forget to turn our gaze beyond our bubble of white privilege) had acknowledged. Insulting our city is like insulting our family. Nobody likes to hear how much ugliness exists in one’s family.

Note: I have been challenged to reflect on my language in the above paragraph. Originally it said “all of us felt like we’d been punched in the gut” and that is not an accurate reflection. Instead, some felt like it was a relief that these stories were finally coming out. I appreciate the challenge and will continue to reflect on how I can speak about this issue through a lens that allows all stories to be heard. That’s part of the reason I’m in this conversation – to look inside for the shadow of colonialism within so that I can step beyond that way of seeing the world and serve as a bridge-builder.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, I began to wrestle with what it would mean for me to be a change-maker in my city. I emailed the mayor and offered to help host conversations, I sat in circle at the Indigenous Family Centre, I accepted the invitation of the drum, and I was cracked open by a sweat lodge.

I shared my interest in hosting conversations around racism on Facebook, and then I waited for the right opportunity to present itself. I tried to be as intentional as possible not to enter the conversation as a “colonizer who thinks she has the answer.” It didn’t take long for that to happen.

Rosanna Deerchild was one of the people quoted in the Macleans article, and her face made it to the front cover of the magazine. Unwillingly and unexpectedly, she became the poster child for racism. Being the wise and wonderful woman that she is, though, she chose to use that opportunity to make good things happen. She posted on her own Facebook page that she wanted to gather people together around the dinner table to have meaningful conversations about racism. A mutual friend connected me to her conversation, and I sent her a message offering to help facilitate the conversation. She took me up on it.

Rosanna Deerchild was one of the people quoted in the Macleans article, and her face made it to the front cover of the magazine. Unwillingly and unexpectedly, she became the poster child for racism. Being the wise and wonderful woman that she is, though, she chose to use that opportunity to make good things happen. She posted on her own Facebook page that she wanted to gather people together around the dinner table to have meaningful conversations about racism. A mutual friend connected me to her conversation, and I sent her a message offering to help facilitate the conversation. She took me up on it.

At the same time, a few other people jumped in and said “count me in too”. Clare MacKay from The Forks said “we’ll provide a space and an international feast”. Angela Chalmers and Sheryl Peters from As it Happened Productions said “we’d like to film the evening”.

With just one short meeting, less than a week before it was set to happen, the five of us planned an evening called “Race Relations and the Path Forward – A Dinner and Discussion with Rosanna Deerchild”. We started sending out invitations, and before long, we had a list of over 50 people who said “I want to be part of this”. Lots of other people said “I can’t make it, but will be with you in spirit.”

In the end, a beautifully diverse group of over 80 people gathered.

We started with a hearty meal, and then we moved into a World Cafe conversation process. In the beginning, everyone was invited to move around the room and sit at tables where they didn’t know the other people. Each table was covered with paper and there were coloured markers for doodling, taking notes, and writing their names.

Before the conversations began, I talked about the importance of listening and shared with them the four levels of listening from Leading from the Emerging Future.

- Downloading:

the listener hears ideas and these merely reconfirm what the listener already knows

- Factual listening:

the listener tries to listen to the facts even if those facts contradict their own theories or ideas

- Empathic listening

: the listener is willing to see reality from the perspective of the other and sense the other’s circumstances

- Generative listening

: the listener forms a space of deep attention that allows an emerging future to “land” or manifest

“What we really want in this room,” I said, “is to move into generative listening. We want to engage in the kind of listening that invites new things to grow.”

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

For the first round of conversation, everyone was invited to get to know each other by sharing who they were, where they were from, and what misconceptions people might have about them. (For example, I am a suburban white mom who drives a minivan, so people may be inclined to jump to certain conclusions about me based on that information.)

After about 15 minutes, I asked that one person remain at the table to serve as the “culture keeper” for that table, holding the memories of the earlier conversations and bringing them into the new conversation when appropriate. Everyone else at the table was asked to be “ambassadors”, bringing their ideas and stories to new tables.

For the second round of conversation, I invited people to share stories of racism in their communities and to talk about the challenges and opportunities that exist. After another 15 minutes, the culture keepers stayed at the tables and the ambassadors carried their ideas to another new table.

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

In the third round of conversation, they were asked to begin to think of possibilities and ideas and to consider “what can we do right now about these challenges and opportunities?”

The one limitation of being the facilitator is that I couldn’t engage fully in the conversations. Instead, I floated around the room listening in where I could. This felt a little disappointing to me, as I would have liked to have immersed myself in the stories and ideas, but at the same time, circling the room gave me the sense that I was helping to hold the edges of the container, creating the space where rich conversation could happen.

After the conversation time had ended, the culture keepers were invited to the front of the room to share the essence of what they’d heard at their tables. Some talked about the need to start in the education system, ensuring that our youth are being accurately taught the Indigenous history of our country, others talked about how this needs to be a political issue and we need to insist that our politicians take these concerns seriously, and still others talked about how we each need to start small, building more one-on-one relationships with people from other cultures. One young woman shared her personal story of being bullied in school and how difficult it is to find a place where she is allowed to “just be herself”. Another woman shared about how hard she has had to work to be taken seriously as an educated Indigenous woman.

After the conversation time had ended, the culture keepers were invited to the front of the room to share the essence of what they’d heard at their tables. Some talked about the need to start in the education system, ensuring that our youth are being accurately taught the Indigenous history of our country, others talked about how this needs to be a political issue and we need to insist that our politicians take these concerns seriously, and still others talked about how we each need to start small, building more one-on-one relationships with people from other cultures. One young woman shared her personal story of being bullied in school and how difficult it is to find a place where she is allowed to “just be herself”. Another woman shared about how hard she has had to work to be taken seriously as an educated Indigenous woman.

One of the people who shared mentioned that the Macleans article was a “gift wrapped in barbed wire”. Those of us in the room have chosen to unwrap the barbed wire to find the opportunities underneath.

Another person said that the golden rule is not enough and that it is based on a colonizers’ view of the world. “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” has to shift into the platinum rule, “Do unto others as they would have you do unto them.” To illustrate his point, he talked about how Indigenous people go for job interviews and because they don’t look people in the eye and don’t have a firm handshake, people assume they don’t have confidence. “Understand their culture more deeply and you’ll understand more about how to treat them.”

As one person mentioned, “the problem is not in this room”, which was a challenge to us all to have conversations not only with the people who think like us, but with those who think differently. Real change will come when we influence those who hold racist views to see people of different nationalities as equals.

There were many other ideas shared, but my brain couldn’t hold them all at once. I will continue to process this and look back over the notes and flipcharts. And there will be more conversations to follow.

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

After we’d heard from all of the tables, we all stood up from our tables and stepped into a circle. We have been well taught by our Indigenous wisdom-keepers that the circle is the strongest shape, and it seemed the right way to end the evening. Once in the circle, I passed around a stone with the word “courage” engraved on it. “I invite each of you to speak out loud one thing that you want to do with courage to help build more positive race relations in our city.” One by one, we held the stone and spoke our commitment into the circle.

We took the energy and ideas in the room and made it personal. Some of the ideas included “I’ll read more Indigenous authors.” “I’ll teach my children to respect people of all races.” “I’ll take political action.” “I’ll take more pride in my Indigenous identity.” “I will host more conversations like this.” “The next time I hear someone say ‘I’m not racist, but…’ I will challenge them.” “I’ll continue my work with Meet me at the Bell Tower.” “I will bring these ideas to my workplace.” “I will find reasons to spend time in other neighbourhood, outside my comfort zone.”

I didn’t realize until later, when I was looking at the photos taken by Greg Littlejohn, that we were standing under the flags of the world. And the lopsided circle looks a little more like a heart from the angle his photo was taken.

This is my Winnipeg. These eighty people who gathered (and all who supported us in spirit) are what I see when I look at this city. Yes there is racism here. Yes we have injustice to address. Yes we have hard work ahead of us to make sure these ideas don’t evaporate the minute we walk out of the room. AND we have a beautiful opportunity to transform our pain into something beautiful.

We have the will, we have the heart, we have a community of support, and we have the opportunity. A year from now, I hope that a different story will be told about our city.

Note: If you’re wondering “what next?”, I can’t say that for certain yet. I know that this will not be a one-time thing, but I’m not sure what will emerge from it yet. The organizers will be getting together to reflect and dream and plan. And in the meantime, I trust that each person who made a commitment to courage in that circle, will carry that courage into action.

more pausing, and, almost always, more vulnerability than ordinary conversations. Yes, some people get nervous about the talking piece (because it puts them on the spot and feels like pressure to say something important), but when they get used to it, (and when they realize that anyone is welcome to pass the talking piece without speaking) almost everyone acknowledges that the talking piece brought something special into the space that they’ve rarely experienced before.

more pausing, and, almost always, more vulnerability than ordinary conversations. Yes, some people get nervous about the talking piece (because it puts them on the spot and feels like pressure to say something important), but when they get used to it, (and when they realize that anyone is welcome to pass the talking piece without speaking) almost everyone acknowledges that the talking piece brought something special into the space that they’ve rarely experienced before.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.