by Heather Plett | Dec 4, 2015 | connection, family, growth, holding space, journey, marriage, parenting

There’s a piece of my story in this unfolding year that I have had a hard time writing about. I still don’t know quite what to say, but I also don’t want to pretend that it’s not going on or that I’m trying to keep it a secret.

This summer, my twenty-two year marriage unraveled and my husband and I are now separated.

That’s the simple version. The more complex version is the part that’s difficult to talk about, because it is not my story alone and I am determined never to write anything that might hurt anyone I care about. My husband, my daughters and I are all fumbling our way through this, trying not to hurt each other, trying to heal from past wounds, and trying to emerge stronger and wiser.

I share it, though, because sometimes people turn to me for expertise on what it means to hold space for people, and I don’t want to pretend that I have figured out everything there is to know about keeping relationships healthy. Like you, I falter sometimes, and I fail people, and I make decisions that might be hard for people to understand. I am still very much on a learning journey.

Early this year, after I wrote the post that went viral, about what it means to hold space for other people, what became more and more clear to me was something I’d woken up to about five years earlier. My husband and I no longer knew how to hold space for each other. We’ve tried and tried, but repeatedly we’ve failed. For my part, I spent too much time judging him and thinking I needed to rescue or fix him, and for his part, he no longer understood me and had no idea how to support the kind of work I was doing or the changes I was undergoing as a result.

For a long time, I tried to tell myself that it didn’t matter that we were in such different places – that I was in this marriage for the long haul and that my daughters were better off with us together – but I could only fool myself for so long. We were hurting each other in our failure, and, after repeated attempts at marriage counselling, it finally became clear to me that we were not doing our daughters any favours by staying in this broken place.

There is much that remains unresolved in this story and I continue to learn from it as I navigate this new path. I stumble sometimes, and then I fall into grace and am given a hand up to get back up on my feet again.

And that is where I will leave this story, in an unresolved place where there is still healing to be done and forgiveness to be offered. I am learning, despite much impatience and struggle, to stay in the unresolved places until what’s meant to emerge can find its own way and time to unfold.

When we see brokenness, our tendency (based in a childish desire for the world to be clean and orderly, black and white) is to rush in to fix it, to find a solution, and to put it back the way it once was. But the invitation of a deepening spirituality is to allow it to remain unresolved, to ask ourselves why we are uncomfortable with it being unresolved, and to consider that perhaps something new wants to grow in its own sweet time without the limitations of “the way things used to be”.

As a writer and teacher, I feel pressure sometimes, on my blog and on social media, to only share a story when it has a complete ending. If I share it when it is still in the unresolved stage, too many people will rush in with advice, solutions, or judgement, responding to their own need to see it fixed in a way that makes sense to them, and then I will feel defeated, inadequate, and not fully heard.

What I most value (and this is why I spend so much time in circles) is to be heard, to be valued, and to be supported in whatever stage of the messiness I am in. This, I believe, is what all of us truly want. Because the best path out of the messiness is rarely the quick fix that first rushes to mind.

I invite you then, to pause for a moment before you respond to my unresolved story or anyone else’s. In your pausing, listen first for what that person most wants from you. And then listen for what is unresolved in your own life that might make someone else’s messy story feel uncomfortable. Because when we sit in the messiness together, we grow truly beautiful and lasting things. That’s what it means to hold space for each other.

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.” – Rilke

Thank you for holding space for me in my unresolved place.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Mar 26, 2013 | courage

Three social scientists once conducted a series of experiments to determine which was more effective, “declarative” self-talk (I will fix it!) or “interrogative” self-talk (Can I fix it?). They began by presenting a group of participants with some anagrams to solve (for example, rearranging the letters in “sauce” to spell “cause”.) Before the participants tackled the problem, though, the researchers asked half of them to take a minute to ask themselves whether they would complete the task. The other half of the group was instructed to tell themselves that they would complete the task.

In the end, the self-questioning group solved significantly more anagrams than the self-affirming group.

The researchers – Ibrahim Senay and Dolores Albarracin of the University of Illinois, along with Kenji Noguchi of the University of Southern Mississippi – then enlisted a new group to try a variation with a twist of trickery: “We told participants that we were interested in people’s handwriting practices. With this pretense, participants were given a sheet of paper to write down 20 times one of the following word pairs: Will I, I will, I, or Will. Then they were asked to work on a series of 10 anagrams in the same way participants in Experiment One did.”

This experiment resulted in the same outcome as the first. People primed with “Will I” solved nearly twice as many anagrams as people in the other three groups. In follow-up experiments, the same pattern continued to hold. Those who approach a task with questioning self-talk did better than those who began with affirming self-talk.

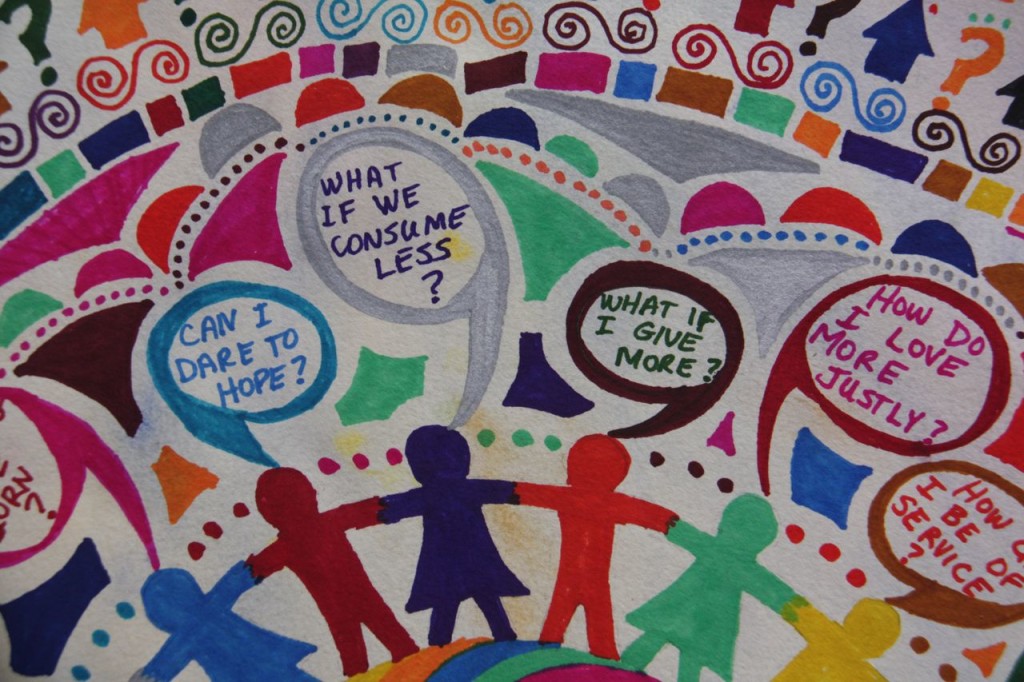

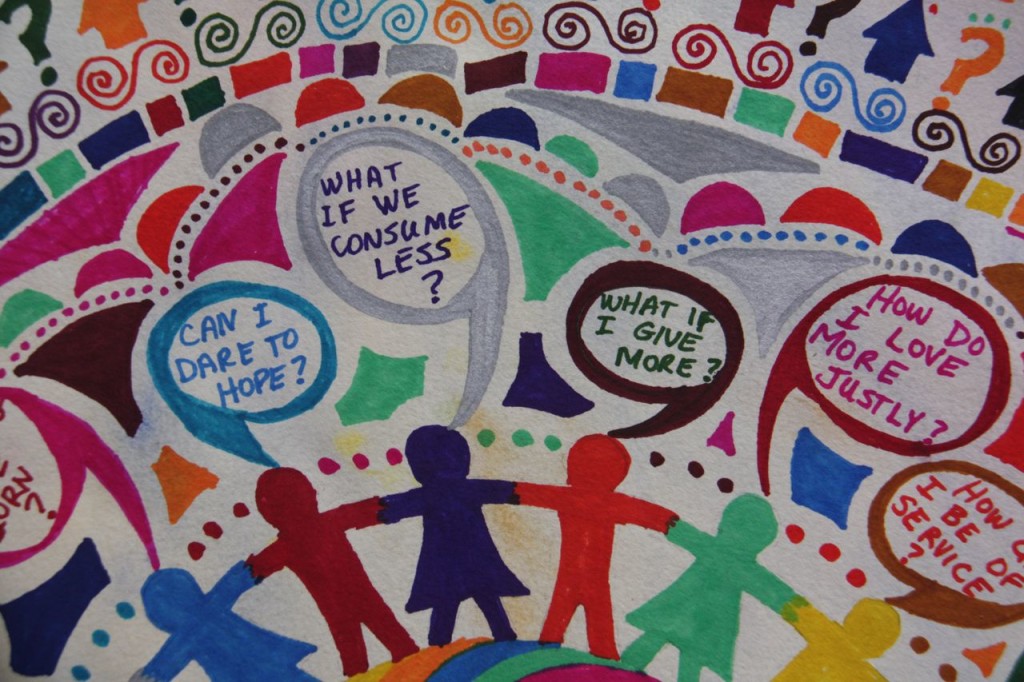

I’ve been intrigued with this research ever since I heard about it a couple of years ago. Because of it, I often invite my coaching clients to create question mandalas rather than setting goals or developing strategic plans. Questions tend to release possibilities in us in ways that goals and declarations do not.

Lately I’ve been playing with this idea again in the area of courage. There are some areas in my life in which I know that I am still letting fear keep me small. I am conflict-averse, and so I shrink back and avoid challenging people when I know that it will make me feel uncomfortable. This has been cropping up in my teaching lately, where I’ve had to challenge some students for plagiarism and other unacceptable behaviours. I cringe any time I have to deal with these situations, and yet I know that I am not doing my students any favours by simply avoiding the tough conversations.

I also still deal with some fear around creating controversy in my work, or teaching things that people don’t like to hear or just don’t receive well. There’s a scared little child inside me who just wants to be liked, and I’m trying to coax her out of her hiding place into a bigger life.

In my effort to build my courage, I decided to use the question technique. Instead of telling myself “I WILL BE COURAGEOUS” each time something fearful shows up, I simply ask myself “Can I be courageous?” Usually the answer to that is “yes”. I carry enough courage stories with me that I can remind myself of times in the past when I’ve been courageous, so I know it can be done. Then, before I take any action, I sit with it a bit more and ask “what will happen if I am courageous?” and I play the scenario out in my mind. I play with the best that might happen and I play with the worst. Usually I realize that the worst is not as scary as I think it will be. If it still seems pretty scary though, I ask myself “can I live with the consequences of this action?” And again, usually the answer is “yes” because my story basket is full of reminders of the tough things that I have lived through in the past.

Almost every time I’ve done this little run-through in my mind, I’ve been able to step into the courageous act more boldly than I expected. In the past week, I’ve been in several of those uncomfortable situations, and each time, I’ve had more courage than I usually do.

And you know what? When I’ve had courage, shored up not by my resolve but by the stories in my story basket, people have almost always responded positively instead of defensively. The question approach not only gives me more courage, it gives me more grace in that courage. Resolve makes me more forceful, questions make me more open. People respond well to openness.

If you want to try the question approach to courage, here’s how to get started:

1. Fill your story basket with stories of courage. Take some quiet time with your journal and write down the stories that come to you when you ask yourself the question, “when have I had courage in the past?”

2. Fill your story basket with stories of resilience. Again in your journal, ask yourself, “when have I lived through difficult situations and survived and thrived?

3. The next time fear shows up, pause for a moment and ask yourself “Can I be courageous”? Reach back into your story basket and pull out the stories that remind you that you CAN.

4. Ask yourself the next question, “What will happen if I am courageous?” Run through the story each way – the best that can happen and the worst. (If you have the time, you may want to journal about this, but you can also run the scenarios in your head.)

5. When you’re sitting with the worst that can happen, ask yourself, “Can I live with the consequences of my actions?” Reach back into your story basket and find the stories of resilience that tell you that YES you can survive the worst.

6. Bonus question… Ask yourself, “Will I be happier if I am courageous or if I shrink from this in fear?” I think you already know the answer to this.

by Heather Plett | Feb 22, 2012 | Creativity, mandala

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

there is a field. I will meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass,

the world is too full to talk about

language, ideas, even the phrase ‘each other’

doesn’t make any sense. – Rumi

“You know what your problem is? You’re too good at seeing both the pros and cons of every situation.” Those words came from a former boss of mine who was somewhat frustrated with me at the time (fifteen years ago) for failing to take sides on an issues. (More specifically, I was failing to take his side.)

Although they were spoken in frustration and were meant as more of an insult than a complement, I have always been grateful for those words. They’ve been some of the most clarifying and helpful words spoken to me in my own self-discovery journey. (Incidentally, that wasn’t the last time I heard similar words from a male boss.)

At the time, though I may have blushed a little at his annoyance, I had a wonderful a-ha moment about a quality I possess that is both a strength and a weakness.

I can sit comfortably in the grey zone.

I don’t need a world painted black and white, true or false, right or wrong, good or bad. Most of the time, I am more comfortable in the centre line between the yin and the yang. I like to probe the depths of both the black and the white and find the grey buried underneath.

In the past, when I’ve been in leadership positions that have required decisiveness and clear direction, this quality has been a bit of a stumbling block. Staff would sometimes get frustrated with me when I’d show up at meetings with more questions than answers. On the other hand, when I invited them into the grey zone with me, there was usually rich and deep conversation that wouldn’t have happened with a more black and white leader.

This is why I am so thoroughly enjoying the work I’m currently doing. When I teach or host conversations or work one-on-one with clients, I invite people into spaces of exploration and questions. Together we explore the beautiful shades of grey in the field beyond “wrongdoing and rightdoing”. I get to ask good questions – the kinds of questions that don’t have immediate answers and require us to practice sitting with them. In classrooms where there are strong-minded, dualistic thinkers, I invite them into the common spaces and help them find shades of truth in the other’s line of thinking. I am happiest when I have helped people poke holes through the boxes in which they’ve placed themselves and they can begin to see that there is light outside the box.

I take Jesus as my model for how to live in the grey zone and still serve as an effective leader. His greatest frustration was with the church leaders who got so lost in rules and doctrine that they didn’t leave room for grace and compassion. Jesus lead as a storyteller whose strength lay in relationships, conversation, and deep and meaningful questions. It’s ironic, isn’t it, that what we now most commonly associate with Christianity today is narrow-mindedness, when Jesus was one of the most radically open-minded leaders in history?

I’ve always found it interesting that Jesus chose to never write anything down. I’m sure he knew that writing things down would give people throughout history the excuse to turn his words into black and white proclamations.

Instead of doctrine and laws, Jesus left us with stories full of grey areas. He invited us into that field beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing.

I am sure that many of the people who resisted Jesus were just like some of my students, who express frustration that there are no clearer rules for right and wrong in the subjects I teach (eg. writing, facilitation, creativity). It’s easier to live in a world of black and white because then we know what’s expected of us and we know when we’ve crossed the lines.

But, unless you’re a police officer enforcing the law, most of the world doesn’t function that way.

We all have to live in the grey zone.

My mandala practice is one of the most beautiful ways I’ve found for living comfortably in the grey zone. Mandalas invite us out into the field that Rumi speaks of, where “the world is too full to talk about language, ideas,” and “even the phrase each other doesn’t make any sense.”

Mandalas invite us out past our linear, problem-fixing mindsets, into a circular world, where truth leads us down spiral pathways instead of straight lines. They help us shift out of the space where language and logic box us in, and into a space where colour, shapes, intuition, prayer, circle, and meditation open the sky above that field.

When I invite people into mandala conversations, we explore the shades of grey that were missing when they first looked at the issue through a black and white lens. After our conversation, they are invited to bring their questions to the mandala where the questions and the ambiguity become things of beauty rather than obstacles to be wrestled with.

I often struggle a bit when I’m describing my mandala practice for people, partly because it’s hard to describe something that engages primarily our right brains with words that reside primarily in our left brain. The grey zone doesn’t translate well in a black and white world.

But the more I do it, and the more I coach people in the process, the more I recognize its value.

We need tools that will help us find meaning in ambiguous spaces.

The mandala is such a tool. I invite you to learn more.