Forgiveness and the death of my son

Handmade clothes my son’s body was dressed in after he was born.

If it hadn’t been for doctors’ errors, I would have a sixteen-year-old son.

Halfway through my third pregnancy, I could sense that something was wrong. My body didn’t feel right. “I feel like I have to re-adjust my hips every time I stand up to avoid the baby dropping from between my legs,” I said to my doctor when I called her. “Something feels too loose down there.”

She sent me to the hospital where an intern taped monitors to my stomach and I lay waiting for the prognosis. “Everything looks normal,” said the intern. “The baby is moving well and the heartbeat is strong. I’ve consulted with your doctor and we’ve decided that there is not enough of an indication of a problem to do an internal exam. At this point in the pregnancy, the risks of that kind of invasiveness don’t seem worth it.”

That was the first mistake. They should have checked my cervix.

A week later, I booked some time off work and visited another hospital for a routine, mid-pregnancy ultrasound. The moment the technician turned the screen away from me, I knew something was wrong. The sudden subdued tone in her voice confirmed my suspicion. An hour later, after an awkward call with my doctor, leaning over the receptionist’s desk and trying not to cry, I was on my way back to the hospital where they would now address the problem that had been missed the week before.

My cervix was open. The signals that my body had sent me were accurate – I WAS too loose down there. I was already four centimetres dilated – four months too soon.

After a variety of doctors visited and asked me the same series of questions over and over again, I finally found myself at a third hospital where I was placed into the hands of the only specialist in the city who had the skill to deal with my problem. That evening, Dr. M. spent nearly two hours explaining the situation to my husband and me.

I had an incompetent cervix. Though it had held firmly through my first two pregnancies, like a rubber band that has lost its elasticity, it no longer had the strength to hold itself closed for the nine months it was required to hold a baby in place. Nobody had an explanation – apparently it just happens sometimes. Because it had been open for awhile, the amniotic sac was bulging out of the gap, which is why I’d been feeling the discomfort a week earlier.

The next morning, after a fitful night that included a panic attack after I listened to the frantic sounds of another mother down the hall giving birth to a dead baby, I was wheeled into the surgical theatre where I was to undergo a cerclage. Like the drawstring of a purse, the doctor would stitch a strong thread through my cervix and then pull it closed, simultaneously pushing the amniotic sac back behind the barrier.

After I was prepped for surgery, Dr. M. entered the room with a young intern. It was a teaching hospital, so I was getting used to students following the teacher around. But I wasn’t prepared for what happened next. Instead of Dr. M., it was the young intern who picked up the needle and stepped between my legs.

Dr. M. read the concern on my face. “Often it’s actually better to have the more experienced doctor watching and guiding rather than doing the stitching,” he reassured me. “It will be okay. She’ll do a fine job.”

That was the second mistake. Minutes later, the faces of both the intern and Dr. M. told me something had gone horribly wrong. “Pull it out,” said Dr. M. “We have to abandon surgery.”

The amniotic sac had been pierced by the needle she was using for the cerclage. My water was now broken. My baby was no longer protected. I would probably go into labour soon and deliver a baby too tiny to survive.

To the surprise of all of the doctors, I didn’t go into labour right away. In fact, hours stretched into days, and the baby seemed to be thriving despite the lack of amniotic fluid or protection from the outside world. Dr. M. watched vigilantly, doing two ultrasounds a day to make sure all of the baby’s organs were functioning properly.

After the failed surgery, I had another fitful night in which I wrestled with the demons that wanted to convince me to point the blame at the doctors. “It’s their fault,” they shrieked in my ear as I fought through the anxiety. “If they had checked you a week ago, or if Dr. M. had done the surgery, you wouldn’t be in this situation, expecting your baby to die at any moment.”

But there was another voice – a quieter voice – underneath the anger and fear. This voice said “You have a choice to make. Blame the doctors and let the bitterness control you, or let it go and choose a more peaceful way through this.” By morning, I had made a choice. I would let it go. Bitterness wouldn’t do me or my baby any good. I wanted to choose life.

The next day, Dr. M. came to see me and at the end of our visit, he paused for a moment. “The intern would like to come see you. She feels horrible about what happened and would like a chance to apologize. Will you see her?”

I took a deep breath. Was I ready to see her?

“Yes,” I said. “I’ll see her.”

A few hours later, she walked into the room. Her eyes filled with tears as she blurted out an awkward apology.

“I know you were doing your best,” I said, “and you made a mistake. I don’t hold that against you. Don’t let this ruin your career as a doctor. Learn from it and keep doing better.”

For much of the next three weeks in the hospital, I felt surprisingly peaceful. I started a gratitude journal and I had many long, luxurious conversations with the friends and family that came to visit. I joked with people who commented on my peaceful appearance that my hospital stay felt a little like being in an ashram – a retreat space away from my busy life that gave me time to reflect on the meaning of my life.

At the end of those three weeks, though, my peaceful state met the crashing waves of despair. I went downstairs for my morning ultrasound visit and discovered that my baby had died during the night. A few hours later, I had to go through the excruciating pain of labour and delivery, knowing the outcome was a dead baby. It was the hardest work I’ve ever done.

As I prepared to go home from the hospital, my breasts filling with milk my son would never drink, I checked in with myself about the choice I’d made three weeks earlier. Now that my baby was dead, could I still forgive the doctors for their mistakes? The stakes were higher – could I make the choice again? Yes, I decided that I could. Choosing not to let go would be to choose bitterness and hatred. I wanted to choose peace and forgiveness. I made that choice again and again in the coming months as the waves of grief came.

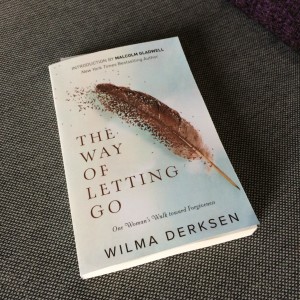

This week, I’ve been reading Wilma Derksen’s new book, The Way of Letting Go, about her thirty-two year journey to forgiveness after her thirteen-year-old daughter’s murder. The term forgive, she says, derives from ‘to give’ or ‘to grant,’ as in ‘to give up.’ Forgiveness is the process of letting go. It “isn’t a miracle drug to mend all broken relationships but a process that demands patience, creativity, and faith.”

This week, I’ve been reading Wilma Derksen’s new book, The Way of Letting Go, about her thirty-two year journey to forgiveness after her thirteen-year-old daughter’s murder. The term forgive, she says, derives from ‘to give’ or ‘to grant,’ as in ‘to give up.’ Forgiveness is the process of letting go. It “isn’t a miracle drug to mend all broken relationships but a process that demands patience, creativity, and faith.”

I’ve known about Wilma since the story of her daughter Candace’s disappearance erupted in the media, five months after I graduated from high school (in 1984). Seven weeks after the disappearance, Candace’s body was found in a shed just a few blocks from her home.

A few years ago, I heard Wilma give a TEDx talk about forgiveness. What stood out about that talk was that, during the trial of the man accused of murdering Candace, Wilma realized that she could not hold both love and justice in her heart in equal measure. Though she longed for justice for Candace’s sake, for the sake of the family that was still with her, she chose love.

After hearing her speak, I reached out to Wilma and we have since become friends. Last year, while she was working on the book, she invited me to lunch to explore the idea of me being a guest speaker at a class she was teaching about forgiveness. Over lunch, she told me about how she had, after more than thirty years of processing her own forgiveness over the murder of her daughter, come to a somewhat different conclusion about forgiveness than what we’d both been taught in our religious upbringing. As she says in the book, it’s a long journey of letting go and making the choice, again and again, to choose love and life, just as I’d done in the hospital. It’s not about denying that you feel anger and hatred or that you want justice, but it’s a conscious choice not to let those things control you.

Toward the end of our lunch date, I decided to share something with Wilma that I’d hesitated to bring up earlier in the conversation – that my marriage had recently ended. I was reluctant to talk about it for two reasons: 1. I didn’t want it to dominate the conversation, especially when the focus was on her course and her work, and 2. since she was an “expert” on forgiveness and I knew her to be a religious person, I was afraid of what she might think of me for having failed at marriage. (I still carried some old shame about the sin of divorce.)

Wilma’s response caught me by surprise. Not only was she compassionate and non-judgemental, but she offered a simple reframing of a story I shared that helped me see even more clearly why the ending of my marriage had become necessary. She held space for me in the beautiful way that only someone who has walked through pain and has learned not to judge herself for her reaction to it can do.

I realized, in that moment, that I had placed Wilma on an impossible pedestal. For more than thirty years, I’d seen the media’s version of this somewhat saintly Christian woman who had some kind of super-human capacity to forgive the most egregious crime against her and her family. But the truth was much more complicated and nuanced (and, in my mind, appealing) than that. She was, just as I was, a very human woman who’d been nearly drowned in intense pain, anger, and fear, and yet she kept swimming back up to the surface in search of the light.

Forgiveness, for her, was not a pie-in-the-sky utopian ideal that meant she could live in peace and harmony with all who’d wronged her. Instead, it was a daily – sometimes hourly – decision to let go of fear, grief, ego, happy endings, guilt, blame, rage, closure, and self-pity.

I didn’t get to raise my son Matthew, but because, like Wilma, I chose forgiveness instead of bitterness, his short life transformed mine and his legacy is present in all of the work I now do. That three week period in the hospital with him was not only a retreat, it was a reconfiguring, sending my life in a whole new direction that lead me to where I am now.

At the end of the book, Wilma admits that her concept and experience of forgiveness are still changing and evolving. I’m with her on that. Life will keep giving us more chances to learn.