by Heather Plett | Feb 18, 2015 | circle, Community, Leadership, Uncategorized

“The moment we commit ourselves to going on this journey, we start to encounter our three principal enemies: the voice of doubt and judgment (shutting down the open mind), the voice of cynicism (shutting down the open heart), and the voice of fear (shutting down the open will).” – Otto Sharmer

Lessons in colonialism and cultural relations

Recently I had the opportunity to facilitate a retreat for the staff and board members of a local non-profit. At the retreat, we played a game called Barnga, an inter-cultural learning game that gives people the opportunity to experience a little of what it feels like to be a “stranger in a strange land”.

To play Barnga, people sit at tables of four. Each table is given a simple set of rules and a deck of cards. After reading the rules, they begin to play a couple of practice rounds. Once they’re comfortable with the rules of play, they are instructed to play the rest of the game in silence.

After 15 or 20 minutes of playing in silence, the person who won the most tricks at each table is invited to move to another table. The person who won the least tricks moves to the table in the opposite direction. All of the rules sheets are removed from the tables.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

Newcomers (ie. immigrants) have now arrived in a place where they expect the rules to be the same, find out after making a few mistakes that they are in fact different, and have no shared language to figure out what they’re doing wrong. Around the room you can see the confusion and frustration begin to grow as people try to adapt to the new rules, and those at the table try to use hand gestures and other creative means to let them know what they’re doing wrong.

After another 15 or 20 minutes, the winners and losers move to new tables and the game begins again. This time, people are less surprised to find out there are different rules and more prepared to adapt and/or help newcomers adapt.

After playing for about 45 minutes, we gathered in a sharing circle to debrief about how the experience had been for people. Some shared how, even though they stayed at the table where the rules hadn’t changed, they began to doubt themselves when others insisted on playing with different rules. Some even chose to give up their own rules entirely, even though they hadn’t moved.

In the group of 20 people, there was one white male and 19 women of mixed races. What was revealing for all of us was what that male was brave enough to admit.

“I just realized what I’ve done,” he said. “I was so confident that I knew the rules of the game and that others didn’t that I took my own rules with me wherever I went and I enforced them regardless of how other people were playing.”

It should be stated that this man is a stay-at-home dad who volunteers his time on the board of a family resource centre. He is by no means the stereotypical, aggressive white male you might assume him to be. He is gracious and kind-hearted, and I applaud him for recognizing what he’d done.

What is equally interesting is that all of the women at the tables he moved to allowed him to enforce his set of rules. Whether they doubted themselves enough to not trust their own memory of the rules, or were peacekeepers who decided it was easier to adapt to someone else who felt stronger about the “right” way to do things, each of them acquiesced.

Without any ill intent on his part, this man inadvertently became the colonizer at each table he moved to. And without recognizing they were doing so, the women at those tables inadvertently allowed themselves to be colonized.

If we had played the game much longer, there may have been a growing realization among the women what was happening, and there might have even been a revolt. On the other hand, he might have simply been allowed to maintain his privilege and move around the room without being challenged.

Making the learning personal

Since that game at last week’s retreat, the universe has found multiple opportunities to reinforce this learning for me. I have been reminded more than once that, despite my best efforts not to do so, I, too, sometimes carry my rules with me and expect others to adapt.

Yesterday, these lessons came from multiple directions. In one case, I was challenged to consider the language I used in the blog post I shared yesterday. In writing about the race relations conversation I helped Rosanna Deerchild to host on Monday night, I mentioned that “we all felt like we’d been punched in the gut” when our city was labeled the “most racist in Canada”. Several people pointed out (and not all kindly) that I was making an assumption that my response to the article was an accurate depiction of how everyone felt. By doing so, I was carrying my rules with me and overlooking the feelings of the very people the article was about.

Not everyone felt like they’d been punched in the gut. Instead, many felt a sense of relief that these stories were finally coming out.

In the critique of my blog post, one person said that my comment about feeling punched in the gut made her feel punched in the gut. Another reflected that mine was a “settler’s narrative”. A third said that I was using “the same sensationalist BS as the Macleans article”.

I was mortified. In my best efforts to enter this conversation with humility and grace, I had inadvertently done the opposite of what I’d intended. Like the man in the Barnga game, I assumed that everyone was playing by the same set of rules.

I quickly edited my blog post to reflect the challenges I’d received, but the problem intensified when I realized that the Macleans journalist who wrote the original article (and who’d flown in for Monday’s gathering) was going to use that exact quote in a follow-up piece in this week’s magazine. Now not only was I opening myself to scrutiny on my blog, I could expect even harsher critique on a national scope.

I quickly sent her a note asking that she adjust the quote. She was on a flight home and by the time she landed, the article was on its way to print. I felt suddenly panicky and deeply ashamed. Fortunately, she was gracious enough to jump into action and she managed to get her editor to adjust the copy before it went to print.

Surviving a shame shitstorm

Last night, I went to bed feeling discouraged and defeated. On top of this challenge, I’d also received another fairly lengthy email about how I’ve let some people down in an entirely different circle, and I was feeling like all of my efforts were resulting in failure.

At 2 a.m., I woke in the middle of what Brene Brown calls a “shame shitstorm”. My mind was reeling with all of my failures. Despite my best efforts to create spaces for safe and authentic conversation, I was inadvertently stepping on toes and enforcing my own rules of engagement.

As one does in the middle of the night, I started second-guessing everything, especially what I’d done at the gathering on Monday night. Was I too bossy when I hosted the gathering? Did I claim space that wasn’t mine to claim? Were my efforts to help really micro-aggressions toward the very people I was trying to build bridges with? Should I just shut up and step out of the conversation?

By 3 a.m., I was ready to yank my blog post off the internet, step away into the shadows, and never again enter into these difficult conversations.

By 4 a.m., I’d managed to talk myself down off the ledge, opened myself to what I needed to learn from these challenges, and was ready to “step back into the arena”.

Some time after 4, I managed to fall back to sleep.

Moving on from here

This morning, in the light of a new day, I recognize this for what it is – an invitation for me to address my own shadow and deepen my own learning of how I carry my own rules with me.

If I am not willing to address the colonizer in me, how can I expect to host spaces where I invite others to do so?

Nobody said this would be easy. There will be more sleepless nights, more shame shitstorms, and more days when my best efforts are met with critique and even anger.

But, as I said in the closing circle on Monday night, I’m going to continue to live with an open heart, even when I don’t know the next right thing to do, and even when I’m criticized for my best efforts.

Because if I’m not willing to change, I have no right to expect others to do so.

by Heather Plett | Feb 17, 2015 | circle, Community, connection, courage, Leadership, Uncategorized

What do you do when your city has been named the “most racist in Canada“?

Some people get defensive, pick holes in the article, and do everything to prove that the label is wrong.

Some people ignore it and go on living the same way they always have.

And some people say “This is not right. What can we do about it?”

When that story came out, some of us felt like we’d been punched in the gut. Though it’s no surprise to most of us that there’s racism here, this showed an even darker side to our city than many of us (especially those who, like me, sometimes forget to turn our gaze beyond our bubble of white privilege) had acknowledged. Insulting our city is like insulting our family. Nobody likes to hear how much ugliness exists in one’s family.

Note: I have been challenged to reflect on my language in the above paragraph. Originally it said “all of us felt like we’d been punched in the gut” and that is not an accurate reflection. Instead, some felt like it was a relief that these stories were finally coming out. I appreciate the challenge and will continue to reflect on how I can speak about this issue through a lens that allows all stories to be heard. That’s part of the reason I’m in this conversation – to look inside for the shadow of colonialism within so that I can step beyond that way of seeing the world and serve as a bridge-builder.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, I began to wrestle with what it would mean for me to be a change-maker in my city. I emailed the mayor and offered to help host conversations, I sat in circle at the Indigenous Family Centre, I accepted the invitation of the drum, and I was cracked open by a sweat lodge.

I shared my interest in hosting conversations around racism on Facebook, and then I waited for the right opportunity to present itself. I tried to be as intentional as possible not to enter the conversation as a “colonizer who thinks she has the answer.” It didn’t take long for that to happen.

Rosanna Deerchild was one of the people quoted in the Macleans article, and her face made it to the front cover of the magazine. Unwillingly and unexpectedly, she became the poster child for racism. Being the wise and wonderful woman that she is, though, she chose to use that opportunity to make good things happen. She posted on her own Facebook page that she wanted to gather people together around the dinner table to have meaningful conversations about racism. A mutual friend connected me to her conversation, and I sent her a message offering to help facilitate the conversation. She took me up on it.

Rosanna Deerchild was one of the people quoted in the Macleans article, and her face made it to the front cover of the magazine. Unwillingly and unexpectedly, she became the poster child for racism. Being the wise and wonderful woman that she is, though, she chose to use that opportunity to make good things happen. She posted on her own Facebook page that she wanted to gather people together around the dinner table to have meaningful conversations about racism. A mutual friend connected me to her conversation, and I sent her a message offering to help facilitate the conversation. She took me up on it.

At the same time, a few other people jumped in and said “count me in too”. Clare MacKay from The Forks said “we’ll provide a space and an international feast”. Angela Chalmers and Sheryl Peters from As it Happened Productions said “we’d like to film the evening”.

With just one short meeting, less than a week before it was set to happen, the five of us planned an evening called “Race Relations and the Path Forward – A Dinner and Discussion with Rosanna Deerchild”. We started sending out invitations, and before long, we had a list of over 50 people who said “I want to be part of this”. Lots of other people said “I can’t make it, but will be with you in spirit.”

In the end, a beautifully diverse group of over 80 people gathered.

We started with a hearty meal, and then we moved into a World Cafe conversation process. In the beginning, everyone was invited to move around the room and sit at tables where they didn’t know the other people. Each table was covered with paper and there were coloured markers for doodling, taking notes, and writing their names.

Before the conversations began, I talked about the importance of listening and shared with them the four levels of listening from Leading from the Emerging Future.

- Downloading:

the listener hears ideas and these merely reconfirm what the listener already knows

- Factual listening:

the listener tries to listen to the facts even if those facts contradict their own theories or ideas

- Empathic listening

: the listener is willing to see reality from the perspective of the other and sense the other’s circumstances

- Generative listening

: the listener forms a space of deep attention that allows an emerging future to “land” or manifest

“What we really want in this room,” I said, “is to move into generative listening. We want to engage in the kind of listening that invites new things to grow.”

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

For the first round of conversation, everyone was invited to get to know each other by sharing who they were, where they were from, and what misconceptions people might have about them. (For example, I am a suburban white mom who drives a minivan, so people may be inclined to jump to certain conclusions about me based on that information.)

After about 15 minutes, I asked that one person remain at the table to serve as the “culture keeper” for that table, holding the memories of the earlier conversations and bringing them into the new conversation when appropriate. Everyone else at the table was asked to be “ambassadors”, bringing their ideas and stories to new tables.

For the second round of conversation, I invited people to share stories of racism in their communities and to talk about the challenges and opportunities that exist. After another 15 minutes, the culture keepers stayed at the tables and the ambassadors carried their ideas to another new table.

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

In the third round of conversation, they were asked to begin to think of possibilities and ideas and to consider “what can we do right now about these challenges and opportunities?”

The one limitation of being the facilitator is that I couldn’t engage fully in the conversations. Instead, I floated around the room listening in where I could. This felt a little disappointing to me, as I would have liked to have immersed myself in the stories and ideas, but at the same time, circling the room gave me the sense that I was helping to hold the edges of the container, creating the space where rich conversation could happen.

After the conversation time had ended, the culture keepers were invited to the front of the room to share the essence of what they’d heard at their tables. Some talked about the need to start in the education system, ensuring that our youth are being accurately taught the Indigenous history of our country, others talked about how this needs to be a political issue and we need to insist that our politicians take these concerns seriously, and still others talked about how we each need to start small, building more one-on-one relationships with people from other cultures. One young woman shared her personal story of being bullied in school and how difficult it is to find a place where she is allowed to “just be herself”. Another woman shared about how hard she has had to work to be taken seriously as an educated Indigenous woman.

After the conversation time had ended, the culture keepers were invited to the front of the room to share the essence of what they’d heard at their tables. Some talked about the need to start in the education system, ensuring that our youth are being accurately taught the Indigenous history of our country, others talked about how this needs to be a political issue and we need to insist that our politicians take these concerns seriously, and still others talked about how we each need to start small, building more one-on-one relationships with people from other cultures. One young woman shared her personal story of being bullied in school and how difficult it is to find a place where she is allowed to “just be herself”. Another woman shared about how hard she has had to work to be taken seriously as an educated Indigenous woman.

One of the people who shared mentioned that the Macleans article was a “gift wrapped in barbed wire”. Those of us in the room have chosen to unwrap the barbed wire to find the opportunities underneath.

Another person said that the golden rule is not enough and that it is based on a colonizers’ view of the world. “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” has to shift into the platinum rule, “Do unto others as they would have you do unto them.” To illustrate his point, he talked about how Indigenous people go for job interviews and because they don’t look people in the eye and don’t have a firm handshake, people assume they don’t have confidence. “Understand their culture more deeply and you’ll understand more about how to treat them.”

As one person mentioned, “the problem is not in this room”, which was a challenge to us all to have conversations not only with the people who think like us, but with those who think differently. Real change will come when we influence those who hold racist views to see people of different nationalities as equals.

There were many other ideas shared, but my brain couldn’t hold them all at once. I will continue to process this and look back over the notes and flipcharts. And there will be more conversations to follow.

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

After we’d heard from all of the tables, we all stood up from our tables and stepped into a circle. We have been well taught by our Indigenous wisdom-keepers that the circle is the strongest shape, and it seemed the right way to end the evening. Once in the circle, I passed around a stone with the word “courage” engraved on it. “I invite each of you to speak out loud one thing that you want to do with courage to help build more positive race relations in our city.” One by one, we held the stone and spoke our commitment into the circle.

We took the energy and ideas in the room and made it personal. Some of the ideas included “I’ll read more Indigenous authors.” “I’ll teach my children to respect people of all races.” “I’ll take political action.” “I’ll take more pride in my Indigenous identity.” “I will host more conversations like this.” “The next time I hear someone say ‘I’m not racist, but…’ I will challenge them.” “I’ll continue my work with Meet me at the Bell Tower.” “I will bring these ideas to my workplace.” “I will find reasons to spend time in other neighbourhood, outside my comfort zone.”

I didn’t realize until later, when I was looking at the photos taken by Greg Littlejohn, that we were standing under the flags of the world. And the lopsided circle looks a little more like a heart from the angle his photo was taken.

This is my Winnipeg. These eighty people who gathered (and all who supported us in spirit) are what I see when I look at this city. Yes there is racism here. Yes we have injustice to address. Yes we have hard work ahead of us to make sure these ideas don’t evaporate the minute we walk out of the room. AND we have a beautiful opportunity to transform our pain into something beautiful.

We have the will, we have the heart, we have a community of support, and we have the opportunity. A year from now, I hope that a different story will be told about our city.

Note: If you’re wondering “what next?”, I can’t say that for certain yet. I know that this will not be a one-time thing, but I’m not sure what will emerge from it yet. The organizers will be getting together to reflect and dream and plan. And in the meantime, I trust that each person who made a commitment to courage in that circle, will carry that courage into action.

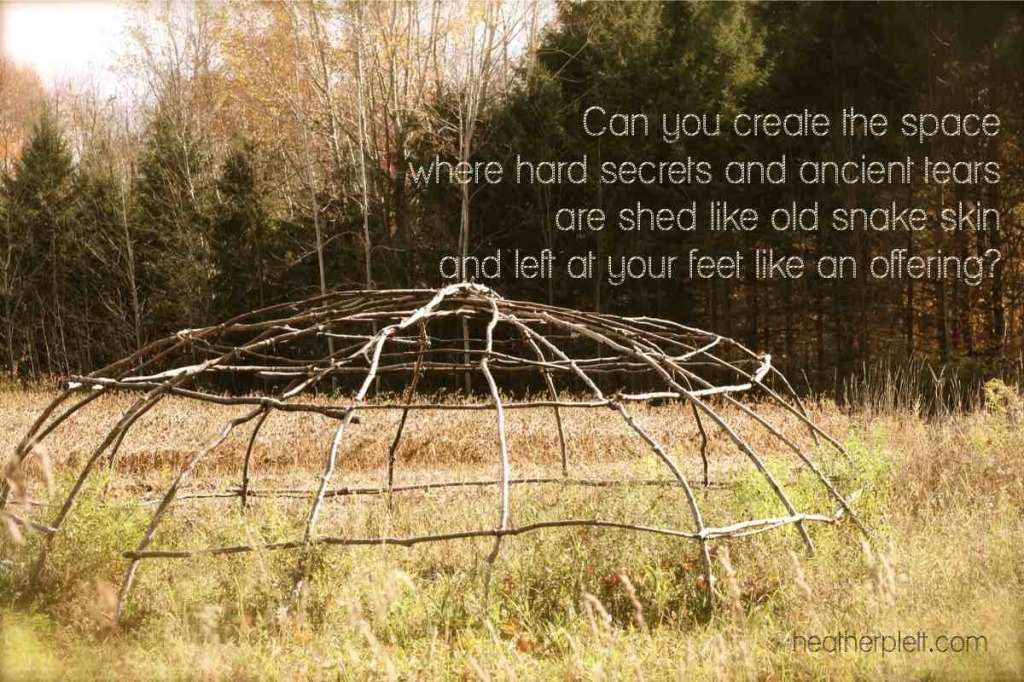

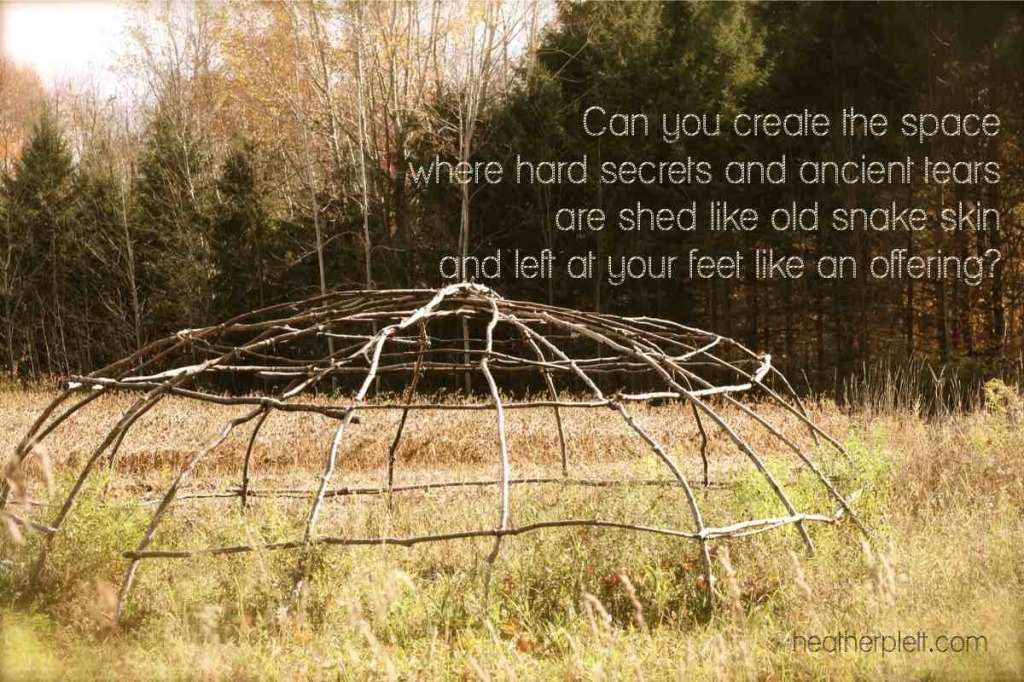

by Heather Plett | Feb 6, 2015 | circle, journey, Labyrinth

I want to tell you about last weekend’s sweat lodge, but each time I sit down to write something, I delete it. The words just don’t come out right. This was an experience beyond words.

What I’m about to share doesn’t come close to expressing it, but it’s the closest I’ve come…

It was intense. It was emotional. It was hard. It was frightening. It challenged me in ways I didn’t expect to be challenged.

I didn’t last inside the whole time. It was too much for me – the tightness, the steam, the extreme heat, the intensity of the drumming and singing, the bodies too close together, the emotions, the fear, my own tendency toward claustrophobia, the memories of trauma. I came out, sat (shaking and weeping) for awhile, and thought I’d go back in, but I couldn’t. When I climbed back inside the open door, my whole body went into panic mode and I had to remove myself.

All I could do was sit outside and weep. I wept and wept. I couldn’t stop the weeping. There was so much that my body wanted to release. Some of it was my own fear, trauma, and grief, and some of it was as ancient as the stones at the centre of the sweat lodge. I was carrying something bigger than myself.

And then, in between the body-wrenching sobs, there was something else. An invitation. A calling. A longing.

There was a whisper in the steam and the drumming and the tears. “It’s time,” it said. “It’s your turn to step forward and become a warrior. It’s your turn to be brave, to be fierce, and to be strong. The earth that you sit on needs you to be. The people you gather in circle need you to be. Your racism-scarred city needs you to be. Everyone is waiting for you to be a warrior.

“But first you have to face this fear. First you have to hold this grief. First you have to prove to yourself that you are strong enough for what this work will require of you.”

That’s why I spent the next few days in silence. Because the sweat lodge is asking much of me.

This is the first piece of writing that emerged, two days after the experience.

Invitation from a sweat lodge

Can you carry the sadness of the world

in your tattered basket

without being pulled in

and smothered by its hungry hands?

Can you hold the container for others,

tenderly weaving the edges so they hold fast,

while trusting that you are held

by invisible hands?

Can you create the space

where hard secrets and ancient tears

are shed like old snake skin

and left at your feet like an offering?

Can you enter the story

without the story consuming you?

Can you walk through the door

without losing your Self?

Can you crack open your heart

and let the tears flow

when the basket becomes too heavy

and the sadness needs to spill out through you?

Can you hold the inherited ache

of your burning sisters

and silenced mothers

without wounding your growing daughters?

Can you sit on the earth,

feel Her deep pain and betrayal

and let it vibrate through your body

without letting it shatter you?

Can you be the storycatcher,

the fire-eater,

the wound-carrier,

without being consumed by the flames?

Though I spent quite a bit of time in solitary silence after the sweat, I knew enough about this kind of deep journey work to know that I needed support. I sent a message to four people who would hold me from afar – an Indigenous elder, a reiki healer, a soulsister/mentor, and a co-host in conversations about trauma and grief. As soon as I shared it with them, I felt lighter and more able to move forward.

Those four women created a container to hold what I was going through. They prayed, they sent messages to check on me, and they cheered me on from afar.

Once again, I am reminded of how important these circles of support are. We need our communities. We need to serve as each other’s containers when we go through difficult journeys. We need to stand side-by-side as we do hard work. We need to find the people with whom, as the quote at the top of the page says, “we can sit down and weep and still be counted as warriors.”

I can become a warrior because I stand shoulder to shoulder with other warriors.

If you are on a similar journey, going deeper into your own calling, excavating the depths of your most authentic self, I want to help create a container for your growth. That’s why I’ve re-opened Pathfinder Circle. This feels like urgent work. We need more changemakers to stand shoulder to shoulder, holding each other when we are weak and cheering each other when we triumph.

It is my hope that six people who want to do deep work, to tap into their own longings and calling, will come together in a virtual space and support, challenge, and encourage each other. Will you be one of them?

by Heather Plett | Jan 30, 2015 | books, Labyrinth

A few nights ago, I was reading in bed when my husband turned to me and said “It must be a good book. You haven’t taken your nose out of it all evening.” He was right – it IS a good book. It’s called Pilgrimage of Desire: An Explorer’s Journey Through the Labyrinths of Life by Alison Gresik. Reading it was like getting cozy in front of the fire with a glass of wine and an old friend who knows your thoughts before you even speak them. Let’s just say Alison and I have a LOT in common.

A few nights ago, I was reading in bed when my husband turned to me and said “It must be a good book. You haven’t taken your nose out of it all evening.” He was right – it IS a good book. It’s called Pilgrimage of Desire: An Explorer’s Journey Through the Labyrinths of Life by Alison Gresik. Reading it was like getting cozy in front of the fire with a glass of wine and an old friend who knows your thoughts before you even speak them. Let’s just say Alison and I have a LOT in common.

I was delighted when Alison got in touch with me (because she saw the parallels between her book and The Spiral Path). We arranged a Skype chat and then decided to interview each other on our blogs. I love her answers to my questions, because even though we think alike and both gravitate toward labyrinths and the Feminine Divine, we both bring something fresh to the narrative that helps us see things in new ways.

1. Tell me about your discovery of the labyrinth and how it helped you reframe your life’s journey.

My first memorable experience with the labyrinth was at a women’s retreat just before I turned 30. I was feeling quite anxious, depressed, and alone — I had been reading some feminist spirituality, Sue Monk Kidd and Carol Christ, and I felt like my image of God had been pulled out from under me.

We walked the labyrinth outside, as the evening was moving toward dusk. I had written down an intention to carry with me to the centre — I wanted God to give me a new name for herself, one that captured her feminine aspect but that also connected to the God of my youth. I was quite fearful that nothing would happen, but I actually had a powerful experience of meeting the Divine there, and receiving a name to call her: Amma.

The ritual around the labyrinth — the pattern marked on the grass, the lanterns, the women walking with me and holding the space outside — provided a strong and visible support for the encounter I had. Actually, I was so freaked out by how powerful the labyrinth experience was that it was a long time before I walked one again — I certainly didn’t make it a habit early on!

I didn’t come to see the labyrinth as a way of understanding my life’s journey until I wrote my memoir. Our year of travel had come to an early unexpected end, and we had settled in Vancouver, BC, where my husband took a job. And I was having a terrible time getting my bearings. It was one of the first major life decisions we’d made without months and years of preparation and choice, and even though it was a good place to be, I felt lost.

I had made several aborted attempts to walk labyrinths when we were in Europe during our year of travel, but something always kept going wrong. And finally, after a year in Vancouver, I was able to walk the Labyrinth of Light on Winter Solstice, which gave me a chance to say goodbye to everything that I’d left behind, to leave a totem of my grief in the centre (actually a lot of snot and tears on my sweater sleeve), and to emerge into this new phase of my life with a lightened heart.

Writing about the last ten years helped me see and make sense of the recurring patterns, the reversals and progress. The geometry of the labyrinth comforted and bolstered me in very tangible ways – physically and metaphorically.

2. Your book is called Pilgrimage of Desire: An Explorer’s Journey Through the Labyrinths of Life (which sounds a LOT like something I’d write, by the way). Can you tell me about the relationship between labyrinth journeys and desire? What does the labyrinth teach us about desire?

I think that desire is what moves us through the labyrinth. There must be something that compels us, draws us forward or pushes us on, and I believe that is desire, a deep urge to go from one place to another. If we don’t want something — if our heart doesn’t want to beat, if our lungs don’t want air — then we’re not alive. And the labyrinth channels and directs that movement, that desire, in its mysterious unfolding path.

I think that desire is what moves us through the labyrinth. There must be something that compels us, draws us forward or pushes us on, and I believe that is desire, a deep urge to go from one place to another. If we don’t want something — if our heart doesn’t want to beat, if our lungs don’t want air — then we’re not alive. And the labyrinth channels and directs that movement, that desire, in its mysterious unfolding path.

Just today I was reading a quotation from Goethe that says, “Desire is the presentiment of our inner abilities, and the forerunner of our ultimate accomplishments.” In other words, desire is our drive to unfold to our full potential. So while the object of our desire might take the shape of something material — a career, a lover, a child, a creative work, a travel destination — underneath it’s a desire to become what we can become.

And the labyrinth helps us trust and follow that desire. It holds our faith and helps us feel safe in a process that can be terrifying.

3. In the book, you mention the concept of “containers of meaning” (correct me if I got the term wrong). I haven’t heard that term before and it intrigues me. It seems to me that both you and I see the labyrinth as a “container of meaning” in our lives. First, explain the term, and then talk about how the labyrinth serves as a container of meaning.

“Meaning container” is a term I learned from Eric Maisel, and essentially it’s anything — an activity, a relationship, a project — that we designate to hold meaning for us. What we do and what we have assume greater significance because they are poured into a meaning container, captured and gathering weight rather than draining away.

I love the labyrinth as a meaning container, because it’s not a static bucket — it’s got flow and change. The labyrinth’s cycles can embrace the meaning of one hour, one day, and an entire life. So for me, the labyrinth holds the significance of that first walk and my connection with Amma, and now it holds my memoir and the story of living and writing it, and it also holds the whole history and symbolism of the feminine. The labyrinth shows me synchronicity — like you and I discovering each other! It’s like a code that communicates volumes in a single image. I feel like I’ve only begun to scratch the surface of what the labyrinth can mean to me.

4. One of the other things you and I have in common is an evolving relationship with the Divine, starting with the traditional Christian view we were raised with and emerging into something different. How did your journey to the feminine Divine change your faith?

In practice, maybe not too much. I still attend an Anglican church, I sing in the choir, and I talk to God in my journal and in my head. I love being part of a community with traditions that celebrate the seasons of the year.

What did change was the tenor of my relationship with God, when she revealed herself as Amma. Leaving behind the judgmental image of a patriarchal God and identifying with Amma as female and as a mother helped me know myself as loved in a way that I hadn’t before. I never felt the need to please Amma, I just knew she thought I was perfect and wanted the best for me. And of course it wasn’t God who changed, just my perception of her. I was able to let her in and be vulnerable with her.

I found this passage in my journal from just before meeting Amma: “I have a fear of exploring being a woman, that I don’t deserve to. That I might be a usurper. Why should I get to enjoy the healing that feminism can provide, if I haven’t been wounded by the patriarchy? Or am I afraid that if I look to closely, I will find those wounds? And even if I find them, wouldn’t other women laugh at them and say, that’s not nearly as bad as what I’ve been through. Those feelings of undeservedness and fear tell me that there’s definitely something up with this feminism thing for me. To think that I’m undeserving of it means I think it’s a good thing. To fear it means that I see it as powerful and life-changing. So those are reasons to keep an open mind, keep reading, and look for the Goddess.”

So coming to Amma was an initiation into the tribe of women that I’d never seen myself as a part of, and that encounter made me care a lot more about the ways gender affects our lives as humans.

5. In the book, you share a very personal account of the complexity of your relationship with your mom and your own experience of the “mother wound” (something that I was wrestling with as I watched my own mom die). Tell me about the experience of writing that so honestly and then taking the courageous step to share it with the world (including your family).

I knew from the beginning that my relationship with my mother was a very important part of the story I wanted to tell about claiming my right to be a writer. And I gave myself permission in the beginning to put everything I wanted to in the book and then sort out all the details later. I had the confidence to do this because I had a wonderful editor (Brenda Leifso) who I really trusted to help me walk the line between what served the story and what was just petty and unkind.

But honestly, when some of the events of our trip were happening as I was writing about it, particularly this conflict with my mom when we were in Detroit, I thought, never in a million will I write about this. I could never expose myself and her like that. And then the process of writing the book showed me what those events meant, and how they connected to what had happened in the past, and I could see they were part of the whole cloth of the story – I couldn’t cut them out.

I already had my parent’s blessing to write about the more ancient history in our family, particularly because we all saw the book as a means of helping others with similar struggles. So we built on that foundation when it came to working through more current events. In fact, the method we arrived at was that I would read them a chapter a week over a video call, because hearing it in my voice and seeing my emotion helped them process it better. Then they would respond, offer their perspective on events, correct my memory in places.

The saving grace, I think, is that my parents know we all have our own take on what happened, and they believe I’m entitled to tell my version. I feel very lucky that they can be that generous.

(By the way, if you want to read a pair of books that get even deeper into the workings of writing about one’s parents, I can highly recommend Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and Are You My Mother?)

In the end I suppose I get my nerve to publish from the belief that this book wanted to be a thing. Pilgrimage of Desire came knocking and I signed on for the ride. I’m just beginning to see the impact the book has on its readers, and I already know that it’s been worth it.

Alison’s book, Pilgrimage of Desire, is now available to order. Go buy it! Trust me on this – you won’t regret it!

Also, go check out Alison’s post where the tables were turned and she interviewed me.

by Heather Plett | Jan 29, 2015 | Uncategorized

Today I was handed a drum, and that may be the most important thing that happens to me all week. Maybe even all year.

All week, I have been wrestling with what my role is in the healing and reconciliation in our city. Because it matters. Because I want to live in a place of love. Because sometimes I hide my head in the sand and stay in my suburban bubble.

I have been immersing myself in stories, conversations, and learning about what brought us here, to this place, where we are called “the most racist city in Canada”. And I have been searching my own heart for what I need to address in order to be a “wounded healer”, to help invite a new narrative. Tears have been shed over the stories of abuse at the hands of my ancestors. And tears have been shed over my own complicating stories – like the day an Indigenous man climbed through my window and raped me, and the journey it took to once again walk down the street without seeing every Indigenous man on the street as my rapist.

Today I attended the weekly sharing circle at the Indigenous Family Centre. Though I’ve been there before, I was feeling nervous, made more painfully aware of the colour of my skin by the many stories in the media. I was afraid I didn’t belong, afraid I look too much like the oppressor with my white skin, afraid I might be challenged to face my own prejudice in that circle, and maybe even a little afraid I might be triggered back to the 21 year old version of me, cowering in my bedroom with the rapist standing over me.

I went anyway, because I have to start with me.

We started with a smudge – a tradition I have come to love over the years. Then one of the leaders picked up one of the drums in the centre of the circle, and walked toward me. Without fanfare, without words, he simply handed it to me. And when he started drumming and singing, I drummed with him. Our drums beat together, like the pounding heartbeat of Mother Earth beneath us. He didn’t care if I didn’t have rhythm or if I didn’t have the right colour of skin, he simply wanted me to be part of that pounding heartbeat.

That simple gesture cracked my heart open. No longer was I the white woman, the stranger, the oppressor. No longer was I “other”. I was simply a member of the circle, holding my place with everyone else.

And now I ask myself… how will that gesture of welcome and grace change me? How will I practice the same radical act of kindness, forgiveness, and community? How will I hand others the drum when they come to the circles I host?

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.