by Heather Plett | Dec 9, 2012 | Uncategorized

Mom with her four children, taken last summer

One of Mom’s last wishes was that we, her children, wouldn’t start fighting over anything after she was gone. She’s seen too many families fall apart after the parents are gone and she didn’t want that to happen to us. Fortunately, we like each other too much to stop talking to each other.

Another of Mom’s last wishes was that we wash all her clothes and give them away. True to character, she wanted to make sure someone would benefit from her departure. In her honour, and to help Mom’s husband prepare to move to a new apartment, two of my siblings and I spent much of yesterday packing up her clothes and other belongings, finding homes for whatever we could.

This afternoon, I took Mom’s two pairs of glasses to an optometrist shop in the mall. “Do you accept old glasses for charity?” I asked. “Yes,” said the young woman, and I handed them to her.

As the glasses changed hands, I thought to myself “this young woman has no idea what the meaning of this moment is. To her, they’re just a couple of old pairs of glasses. She has no idea that they were once worn by the woman I loved most in this world. She has no idea that I’m handing them over to her because I’m living out the legacy of generosity that this woman taught me. She has no comprehension of the thousands of times I looked through those glasses to the eyes that smiled behind them. She doesn’t know that these glasses are connected to the face that was love and warmth and home for me.”

The woman thanked me and I turned away, tears in my eyes. Even though to her it was an ordinary moment in an ordinary day, it was a sacred moment to me.

As I walked away, I wondered “how many moments have I missed that were sacred for other people? How many times have people done or said something significant in my presence and I have (unintentionally, of course) simply brushed the moment off as mundane, ordinary, or even boring? How many stories have I heard from people that took all their courage to share and I have simply assumed they were ordinary stories that had no meaning?”

I took the thought a little further and wondered what would happen if I began to live with the intention of treating every moment as sacred.

What if I treat every encounter I have – with strangers, friends, or family – as if it might be the moment that the Sacred speaks to them? What if I assume that the people I meet could be facing monumental change or be floundering in oceans of grief and the simple encounter with me might feel like a life-line or a place of safety for them? What if I begin to look for the Sacred in each person I meet, expecting to witness something in them that is meant to speak to me? What if I assume a life could be altered by any ordinary smile, kind word, or gracious apology? What if I listen to every story that is shared, believing that it takes courage to share it and that my listening elevates the sacred in the moment for the person who is sharing it?

I can only imagine that, if this becomes my intention, I will live out the legacy of love and generosity my Mom left behind in her last wishes. There won’t be much fighting among my siblings with her life as our model.

by Heather Plett | Dec 4, 2012 | beauty

The woodpecker that visited Mom's feeder shortly after she died, photo by my sister Cynthia

In the last few months of her life, Mom spent a lot of time watching birds. I often sat and watched with her, marvelling at the variety that came to visit. We don’t have much of a history of bird-watching in our family, but we do have a history of paying attention to nature. One of the things that came up at Mom’s funeral was that whenever she went on road trips, she always hoped she’d be the first to spot wild animals. I’ve always been the same.

On one of our last visits, my sister and I spotted a large bald eagle perched in a tree not far from Mom’s house. It’s unusual to see bald eagles where we live, so it seemed an omen of sorts – perhaps bearing a message that our lives were about to change.

Two weeks ago, I brought a new bird book to Mom’s house, hoping we’d get to spend many hours leafing through the pages, trying to identify the birds that visit. Mom never looked at it. That was the day she began slipping away.

The next day, I was teaching at the university, but probably didn’t communicate much through my distraction. I kept my cell phone close, knowing I could get a call at any minute. At noon, after hearing from my brother that her health had declined quickly in the last 24 hours, my sister and I rushed out to be with her.

Before going, though, I made a quick trip to the bookstore. My friend Barbara had mentioned the book When Women Were Birds, by Terry Tempest Williams, and I knew that I had to have it. It’s a collection of short pieces on voice that Williams wrote after her own mother died. I tucked it into my purse.

Mom’s health declined so quickly that day that we were certain she would not live until morning. Her strength disappeared, her voice reduced to a whisper, her mind started slipping away, and she stopped eating and drinking. My siblings (two brothers and a sister) and my mom’s husband all sat with her, comforting her, singing hymns, reading her favourite Bible passages, and praying.

She didn’t go that night. Instead, she stabilized and for the next three days, remained essentially the same. There were restless periods when we had to move her from bed to easy chair or back again (she was light enough by then that any of us could carry her), there were many times when her breathing became so difficult we were sure it couldn’t go on, and some moments her mind was more clear and she was able to communicate, but there were never any moments when we thought things were turning around. We knew that any breath could be her last.

For the rest of the week, there was always at least one or two of us at Mom’s side (along with family and friends that visited), keeping vigil, making sure she didn’t try to get out of bed on her own diminished strength, putting ice chips on her tongue when her throat was scratchy, or just holding her hand. During one of those times, when Mom was sleeping fairly peacefully in the bed, I picked up my new book and started reading.

Terry Tempest Williams’ mother told her, “I am leaving you all my journals. But you must promise me that you will not look at them until after I am gone.” After her mom died, Williams found three shelves of beautiful clothbound journals. Every one of the journals was completely empty.

When Women Were Birds is Williams’ meditation on what those journals mean and what it means for a woman to have a voice. All of this is set against a backdrop of bird-watching and bird-listening. Birds, after all, never question whether or not they should sing and they never try to sing in a voice that’s not their own.

Raised in a Mormon home, where women’s voices were often silenced, Williams struggled with finding her own voice and trusting it to speak of those things she cared about. She cares deeply about the natural world and we now know her to have a clear and resonant voice on issues related to environmental abuse, but before she could become the advocate she is today, she had to go through much learning, grief, and growth.

To say that it was profound to read When Women Were Birds at my mom’s deathbed, while I witnessed Mom’s voice and spirit decline and disappear, would be an understatement. There were so many layers of significance going on for me at that time that I can hardly begin to explain what it meant.

My mom lived most of her life without trusting her own voice. Always insecure, she believed she had little of value to say. She was always quite certain that there were smarter people than her who should be listened to, and so she believed her voice meant little. It didn’t help that she was raised in a religious tradition that didn’t encourage women to speak, or that she married two men who were both more confident or sure of their own opinions than she was. What she failed to recognize was the fact that her “voice” came through loud and clear in the great love she offered people. She didn’t need to speak to be a healer of wounded souls.

To be honest, there’s always been some disconnect with my Mom when it comes to trusting my own voice. Though I never doubted that she loved me and was proud of me, she didn’t really understand what I felt I needed to speak of in the world. When I was writing plays, she came to watch, but usually said “it was good, but I didn’t really understand what was going on.” The same can be said for my published articles and blog posts. She always claimed that she was “too stupid to understand”.

In recent years, while I’ve been growing my body of work, I’ve had a hard time sharing what I do with my Mom. Some things – like the teaching I do at the university – was fairly easy for her to grasp, but other things just didn’t make sense to her. For one thing, she remained committed to a Christian tradition that frowned upon women in leadership, so when I started teaching women how to lead with more courage, creativity and wild-heartedness, it didn’t really fit with her paradigms. Nor did it make sense to her that I would seek a feminine divine or a feminine way of looking at spirituality.

Reading the book at Mom’s bedside left me somewhat conflicted.

On the one hand, I mourned the fact that Mom had been trapped by a lack of self-esteem and a religion that kept her voice silent. On the other hand, I honoured the fact that Mom always lived her life rooted in a deep love for other people.

On the one hand, I was disappointed that I’d never been able to fully share the importance of my work with my Mom. On the other hand, I’ve been taught by her to use my God-given gifts to make the world a better place.

On the one hand, my Mom was never able to fully validate or appreciate my writing or teaching. On the other hand, she’d raised me with so much love that I have the confidence I need to keep doing it without external validation.

On the one hand, I wished I could tell her about the work I’m doing for Lead with your Wild Heart and how I believe it will be life-changing for me and the women who participate. On the other hand, I knew that just sitting there and being present in the grief, without trying too hard to make it something it isn’t, was going to leave me with profound lessons that will enrich my teaching for years to come. And I knew that some of my wild-heartedness had been learned by watching her.

There have been times, in the last year and a half since Mom received her cancer diagnosis, that I’ve felt sure that I’d need to resolve some issues with my Mom. I thought I’d need to have a few more heart-to-heart talks with her before she died, finally helping her to understand where my views are different from hers and why I feel called to do this work that I do. But then, in recent months, that began to soften. I no longer felt the need for resolution. Instead, I simply felt the need to be there, to sit with her and enjoy her presence and bask in her love in those final months.

In the last week of her life, we didn’t do much talking. There was much that had been left unsaid. But that was okay. I didn’t need her to understand me. I didn’t need her to validate my choices. I simply needed to trust that she loves me and that she always has.

In the last week of her life, we didn’t do much talking. There was much that had been left unsaid. But that was okay. I didn’t need her to understand me. I didn’t need her to validate my choices. I simply needed to trust that she loves me and that she always has.

Once, when Mom was sitting in her big easy chair, she turned to me as if to communicate something. I leaned in to hear her whisper, but she didn’t speak. Instead she put her hand on my head and held it there while she looked deeply into my eyes, like a priest offering a blessing. My eyes filled with tears.

Another time she became restless and I thought she wanted to be moved, so I bent my head and prepared to pick her up. Instead, she wrapped her arms around me and kissed the top of my head several times, and then she smiled. I smiled back.

By Thursday, I was pretty sure she was slipping away. Her eyes had become more distant and she spent less and less time in the plane of reality that the rest of us remained in. By then, we were ready to let her go. I went home that night for the first time, hoping to get a few more hours of sleep. Around three, when my brother Dwight and sister Cynthia were sitting with her, she became suddenly more clear and happy than she’d been in a long time. “I made it!” she said. “I’m here!” When Dwight asked if she was in heaven, she said “yes!” And then it seemed like she was being introduced to people who’d passed before her.

At 4:00, they called me and woke my brother Brad. I rushed to her house, hopeful that a deer wouldn’t jump out at me on the dark highway. Instead, a ghostly bird fluttered through my headlights. By the time I got there, she’d already died. She stopped breathing for a few minutes, but when Cynthia said “oh Mom – you were supposed to wait until Heather got here!” she started up again. When I arrived, she was breathing but in a coma. There was no more life in her eyes. I sat with her for a few hours, and then as morning came, her breath became more and more fluid-filled. At 8:26, she finally stopped.

Shortly after that, a woodpecker came to Mom’s feeder and Cynthia snapped the photo at the top of this page. A few days later, the day we buried Mom next to Dad in the small town where we grew up, Cynthia spotted another bald eagle.

This week, I am back at work, writing more lessons for Lead with your Wild Heart. No, it’s not something my Mom understood, but that’s okay. I know that I have her blessing to use my gifts and share my voice, and this is what I am called to do.

Like a bird, I will go on singing, and the grief in my voice will only make it richer.

“Once upon a time, when women were birds, there was the simple understanding that to sing at dawn and to sing at dusk was to heal the world through joy. The birds still remember what we have forgotten, that the world is meant to be celebrated.” – Terry Tempest Williams

by Heather Plett | Nov 30, 2012 | Uncategorized

Mom & I, in the summer when she thought she'd beaten cancer

I sit down to write a blog post, and all that comes out is… I don’t have a mother anymore.

I try to write in my journal, and the only words that show up on the page are… I’m an orphan now. I don’t know how to be an orphan.

I turn to my work, and all I can do is stare at the blank page and think… Who am I now that both of my parents are dead?

I wander around the house aimlessly. I can barely focus enough to wash the dishes. I watch mindless TV. I putter. I sit long minutes lost in thought.

I phone my mom’s husband, my mom’s cheery voice comes on the answering machine, and I fall to pieces. It’s hard to leave a message when the one I really want to talk to won’t return my call.

Last week, when Mom was slipping away, and her mind was no longer always clear, she looked at me with sadness in her eyes. “I don’t know how to do this,” she said, in her nearly invisible voice. “I know Mom,” I said. “I don’t know how to do this either.”

And that’s how I still feel. “I don’t know how to do this.”

I don’t know how to get used to the fact that I can’t pick up the phone and call Mom. I don’t know how to write this grief in any way that makes sense. I don’t know how to tell you the story of what it meant to watch her die. I don’t know how to make meaning of the days of vigil, watching her slip away, carrying her emaciated body from bed to chair when she became restless, waking in the night to care for her, listening to her gurgling hanging-on-to-life breath.

I don’t know how to speak with this lump in my throat.

I don’t know how to be at the top of the family tree, the oldest woman in my line of descendants. I’m much too young to be the matriarch. I don’t want to take on that responsibility.

Last Saturday, when I was supposed to be hosting a day retreat for women of courage, I spent the day planning my Mom’s funeral. Instead of being the teacher, I was the student again, forced to learn new lessons in courage.

Grief is a cruel teacher. I want to skip this class. I want to rebel, climb out the window, and run away to a place where my Mom and Dad and son are still alive. I don’t want to stay here and write the test. Not again, please. I’ve been through this class a few times already – can’t I get an exemption this time? Can’t I just be the teacher now without having to learn any more of these difficult lessons?

I haven’t been given a choice though. I have to stay here and learn the lessons I have yet to learn. I have to pay attention – to be present in the pain, to let the tears come, to let the panic wake me in the night, to remember again and again what her empty eyes looked like when the breath left her body. I have to let another death change my life.

I have to bear the burden of this fresh crack in my heart, remembering that the pain is telling the story of the privilege of being loved. I have to remind myself that my heart can break without falling apart because it has been made resilient by love. My life can feel this emptiness because I’ve known fullness.

I will get angry at the teacher now and then, and I will lay my head down on my desk when the learning feels too heavy, but I will stay here in this class. There’s nothing “fair” about it, and right now the pain is blinding me from seeing the blessings, but, in the end, I know I will be richer and wiser for having had the courage to love and the courage to grieve.

My heart is broken, but I will learn to dance with a limp.

“You will lose someone you can’t live without,and your heart will be badly broken, and the bad news is that you never completely get over the loss of your beloved. But this is also the good news. They live forever in your broken heart that doesn’t seal back up. And you come through. It’s like having a broken leg that never heals perfectly—that still hurts when the weather gets cold, but you learn to dance with the limp.” ― Anne Lamott

by Heather Plett | Nov 26, 2012 | Uncategorized

Just like we did at Dad’s funeral nine years ago, each of the four siblings shared a tribute to our beautiful mom. This is what I shared…

I’m curious about something… How many people in this room have had a chance to taste some of my mom’s baking? Some of you may not even know you’ve had it… If you attended a potluck either in Landmark or in Arden, you probably had some. If you attended Cynthia’s wedding, you probably had one of her buns. If you worked with me or my siblings, or visited our homes, you may have had something she’d sent us home with. There was always lots to go around.

I’m curious about something… How many people in this room have had a chance to taste some of my mom’s baking? Some of you may not even know you’ve had it… If you attended a potluck either in Landmark or in Arden, you probably had some. If you attended Cynthia’s wedding, you probably had one of her buns. If you worked with me or my siblings, or visited our homes, you may have had something she’d sent us home with. There was always lots to go around.

There’s a story in the Bible about Jesus looking around and seeing a lot of hungry people and realizing they needed to be fed. With only a few loaves and fishes, he managed to feed 5000 people. In the process, he gave them not only food, but love. Well, I think my Mom took that story to heart and made it her personal mission to feed all the hungry people she could find. With a few of Dad’s farm eggs, some Prairie Dawn flour, and her magical hands, she too fed 5000 people. Even in her final days, when she could no longer stand and could barely speak, she still tried to get out of bed a few times, insisting that it was time for us all to sit down at the table and have something to eat.

That’s how our Mom lived her life – always giving, always loving, always making food for people. She never had much money, and yet she found ways to give that went far beyond what monetary riches could have done. Just like the story of the feeding of the 5000, I believe God worked a miracle through her hands.

Paul said yesterday that one of the reasons he married Mom was because he could see she had servant hands. He couldn’t have been more right about that assessment. St. Francis of Assissi is quoted as saying “Spread the good news, if all else fails, use words.” Mom didn’t need a lot of words to spread God’s love – she didn’t need to preach a sermon or write a book – she just needed her beautiful, loving hands.

In the last week of her life, when my siblings and Paul and I cared for her, several visitors stopped by or phoned to show their love for Mom. In the stories that were shared, we heard these four common themes that mirrored what we already knew about Mom:

- Mom was one of the most loving and generous people they’d ever known.

- Mom liked to feed people.

- Mom loved adventure.

- Mom loved to play games.

Growing up, most kids go through a phase in their lives when they feel embarrassed about their Moms, for one reason or another. I don’t ever remember feeling that way, partly because my friends all thought I had one of the coolest and kindest Moms around. Some of my friends still talk about how good she was at telling stories in church, bringing fun and life into everything. She was also the most fun to have at the Sunday School or community picnics, because she’d rather have a water fight with the kids than sit in boring conversation with the grown-ups. I think sometimes my friends came over as much to hang out with Mom as to visit me.

She would never have said this about herself, but my mom was a healer – she helped God heal wounded souls. Henri Nouwen talks about the wounded healer, who is able to reach out to people from the place of their own woundedness. Mom was one of those wounded healers. She suffered some pretty deep wounds in her early life, losing two brothers and her mom, and that allowed her to be deeply compassionate to the wounded people she encountered in the world.

Growing up, we had to get used to a lot of wounded people spending time in our home. Whether it was the young children whose Mom was unable to care for them, or a young mom who was going through trouble in her marriage, Mom felt compelled to bring them home and wrap them in her love. Some people bring wounded animals home, Mom brought wounded people – and she didn’t let them go until they’d been well fed and well loved. Just recently she told me about some lonely teenage girls who started to drop by and play games with her and Paul. I had to chuckle, because I knew Mom couldn’t resist opening the door to them, even when her own health was failing.

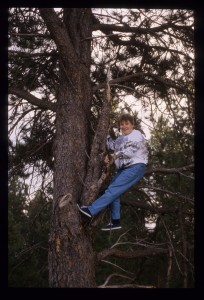

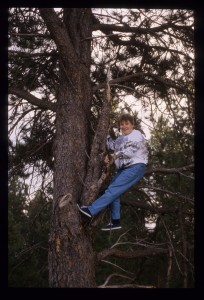

At the back of the program, you’ll find a photo of Mom climbing a tree. A tribute to our Mom wouldn’t be complete without talking about how she loved to climb almost anything she could find to climb, especially trees. My kids were always proud of the fact that they had one of the only Grandmas who would climb trees with her grandchildren. She’d also climb big rocks or mountains or climbing walls. When she went to seniors camp a couple of times with Paul, she came home quite proud of the fact that she’d been the fastest one (or sometimes the only one) up the climbing wall. One of her friends told me that just this past summer on a trip they’d taken together, when Mom thought she’d beaten cancer, she’d found every opportunity she could to climb things. Right until the end, she lived life to the fullest.

At the back of the program, you’ll find a photo of Mom climbing a tree. A tribute to our Mom wouldn’t be complete without talking about how she loved to climb almost anything she could find to climb, especially trees. My kids were always proud of the fact that they had one of the only Grandmas who would climb trees with her grandchildren. She’d also climb big rocks or mountains or climbing walls. When she went to seniors camp a couple of times with Paul, she came home quite proud of the fact that she’d been the fastest one (or sometimes the only one) up the climbing wall. One of her friends told me that just this past summer on a trip they’d taken together, when Mom thought she’d beaten cancer, she’d found every opportunity she could to climb things. Right until the end, she lived life to the fullest.

When I turned 40, I decided to mark it by skydiving. Most Moms would try to dissuade their daughters from taking a foolish risk like that, but not my Mom. She came to watch and was jealous that she wasn’t the one jumping out of the plane.

It’s been really hard to write this tribute, and even now it feels so incomplete, because I just don’t know how to wrap words around a love and a passion for life like Mom had. Words seem trivial and almost trite. I know that the best way to write this tribute is to write it on my heart and to spread the love Mom gave to me to everyone I meet. I won’t be feeding the 5000 (that’s not my particular gift), but I will promise to live in the way that my Mom taught me – serving as a wounded healer, loving the lonely, using my gifts to make the world a little better, and relishing every adventure and tree-climbing opportunity I can find.

If you want to honour my Mom, I invite you to do the same. Spread the love of God in everything you do. Enjoy life to the fullest. Climb trees when you need a little excitement. And eat good food – especially buns and butter tarts.

Mom used to say that she didn’t expect many people to show up at her funeral. We’d always laugh at her when she said that, because we had a much greater sense than she did just how many people she’d touched in her life. Along with her great love, she had great humility. But a love like that spreads (especially when it’s clothed in humility), and now I stand in front of a church full of people who’ve been touched by her in one way or another. All week, I’ve been getting emails and phone calls from other people she’s touched who couldn’t be here today, including one from a man she befriended in a hotel in Colorado this past May.

What a legacy she has left! The love she shared isn’t easily forgotten. Thank you for proving her wrong and filling this room. If Mom were here, she would have found the most wounded people in the room by now and given them each a hug. I could really use one of those hugs right now.

by Heather Plett | Nov 25, 2012 | Uncategorized

A week ago, we knew she was slipping away. My siblings and I dropped everything and went to her side. We were with her almost all week, caring for her in her home so she didn’t have to go to the hospital. In the early hours of Friday morning, November 23rd, all four of us gathered, together with her husband, to watch her make the final transition from this life to the next.

My life is forever changed. There is no way to put this into words yet, but I will, some day. For now, I will simply sit with the grief of being a motherless, fatherless daughter.

Her funeral is on November 26th, at 2:00 at Prairie Rose EMC Church in Landmark, Manitoba. More details here (scroll down to Margaret Plett Vanderwoude).

Her obituary can be found here.