by Heather Plett | Mar 20, 2018 | Uncategorized

I am far from an expert in issues related to diversity, inclusion, or decolonization but because my work involves holding space for increasingly complex conversations in increasingly complex environments, I make it my mission to learn as much as I can in order to do better and to serve better (and to pick myself up after my mistakes). Especially as someone who has (largely) benefited from a colonial system that has harmed others, I take it as my responsibility to face my own discomfort in order to work toward a better future. A lot of damage can be done in a space where we have unexamined privilege and power imbalances, combined with a conversation host who has not done some work in facing her own unconscious bias, so I am trying (with as much humility as I can) to decolonize myself and the spaces where I work.

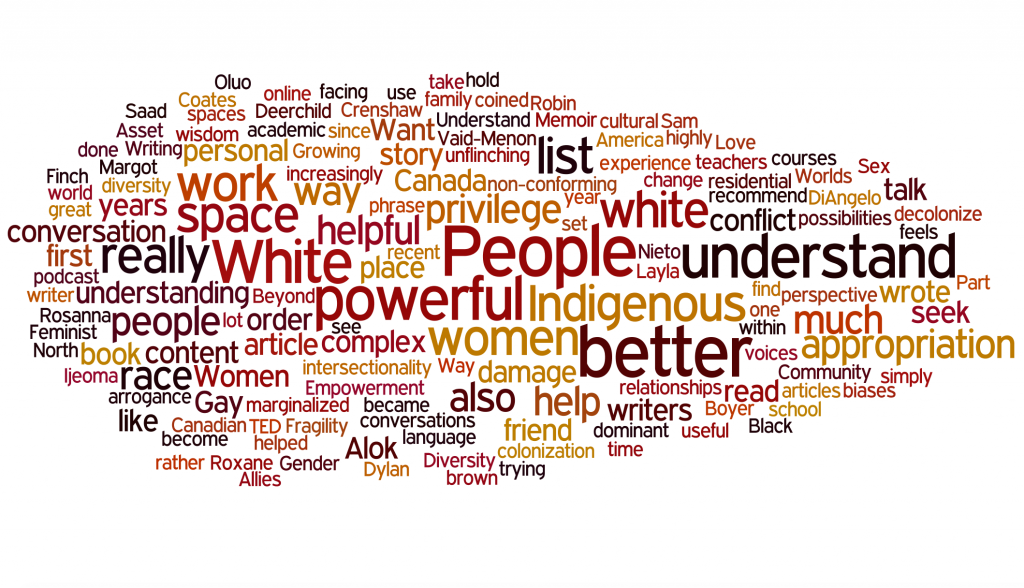

A couple of years ago, I set an intention to spend a year decolonizing my bookshelf and centring marginalized voices by reading only books written by writers who were not from the dominant culture. (This year, I’m trying to do the same with courses, workshops, and conferences I attend.) I wasn’t entirely successful (I wrote about that here), but I was, nonetheless, radically changed by the experience. My worldview was expanded, I became much more aware of my own unconscious biases, and my ability to hold space for brave conversations was considerably stretched. AND… I discovered that I actually loved this shift. Now I find myself gravitating toward these writers because they inspire and challenge me and bring a lot of richness to my life. In the two years since this pledge, I still rarely seek out the most common writers from within the dominant culture, but instead, seek out those working at the edges in more complex spaces (whose ideas are less amplified by mass media, publishing houses, etc.).

People often ask me to provide them with resources that will help them stretch their worldviews, decolonize themselves, and hold space for more complexity and diversity, so I’ve put together the following list of books, articles, and videos that have influenced me in recent years. Most of the voices on this list are from non-dominant groups. (I left fiction off this list, simply because the possibilities for that list felt too endless.)

Before I go there, though, I highly recommend that you also seek out teachers from within these groups that you can PAY FOR what you’re learning. A good place to start is the online course Diversity is an Asset, or a deeper version, Social Justice Intensive, by my friends Desiree Adaway and Ericka Hines. (I participated in Diversity is an Asset the first time they offered it, and because I know that they are both life-long learners with insatiable hunger for evolving ideas, I know that the content has grown even better since then.)

(Note: This list is in no particular order. And there are things missing from it that I simply forgot to save links for.)

Articles and blog posts:

- Intent vs. Impact: Why your intentions don’t really matter (this article helped me understand the damage we do when we try to hide behind “well I didn’t really MEAN it that way”)

- White Women’s Tears and the Men Who Love Them (this is one of the first articles that helped me understand the damage we do when we centre our own feelings over those more marginalized than we are)

- What reconciliation feels like to people “locked in the bathroom” for a century, by Niigaan Sinclair (an Indigenous perspective on colonization and the efforts to “reconcile”)

- What cultural appropriation is and why you should care, by Shree Paradkar (a well-thought-out response to some recent controversy in Canada about an “appropriation prize”)

- A short comic that provides a simple and profound understanding of privilege, by illustrator Toby Morris

- Dear White People, by Bayo Akomolafe (an African man’s perspective on colonialism and appropriation)

- Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, by Kimberle Crenshaw (the original piece in which she coined the phrase “intersectional feminism”)

- The Cycle of Socialization, by Bobbie Harro (helps to gain a better understanding of how we were socially conditioned to think and behave the way we do)

- Please don’t tell me I’m in a “safe place”, by Jamie Marich, PhD (on holding space for trauma and not assuming you understand what makes another person feel safe)

- From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces, by Brian Arao and Kristi Clemens (the academic article that first introduced me to the concept of Brave Space, which I now use in my work)

- White People: I Don’t Want You To Understand Me Better, I Want You To Understand Yourselves, by Ijeoma Oluo

- Nine Phrases Allies Can Say When Called Out Instead of Getting Defensive, by Sam Dylan Finch (helpful language to help us stay in the conversation without arrogance or defensiveness)

- Strategies in Addressing Power and Privilege, by Leticia Nieto, Psy. D., and Margot F. Boyer (a helpful framing of status, rank, and power that I use in courses I teach)

- White Fragility, by Robin DiAngelo (this is the academic article in which DiAngelo coined the phrase “white fragility”)

- Here’s How We Can Center Queer & Trans Survivors In The #MeToo Movement, by Neesha Powell (a great reminder of the people who get overlooked in movements for social change)

- Understanding White Privilege, by Francis E. Kendall, Ph.D (understand white privilege as an institutional (rather than personal) set of benefits granted to those of us who, by race, resemble the people who dominate the powerful positions in our institutions)

- The Radical Copyeditor’s Style Guide for Writing About Transgender People (so we can do better in how we include people in our language)

- Six Backhanded “Compliments” That Mentally Ill People are Tired of, by Sam Dylan Finch (we can do better in holding space for those with mental illness

- Indigenous Nationhood Can Save the World, by Niigaan Sinclair (how we can all benefit from a more Indigenous perspective on nationhood)

Podcasts and Videos:

Non-Fiction/Teaching Books:

- Beyond Inclusion, Beyond Empowerment: A developmental strategy to liberate everyone, by Leticia Nieto with Margot F. Boyer, Liz Goodwin, Garth R. Johnson & Laurel Collier Smith (a powerful analysis of the psychological dynamics of oppression and privilege – useful especially for conversation hosts)

- The Inconvenient Indian: A curious history of Native People in North America, by Thomas King (one of the best resources to help with an understanding of colonization in North America – heavy content, but surprisingly easy to read and rather humorous)

- Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, by adrienne marie brown (an invitation to better understand personal and collective relationships with change)

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants, by Robin Wall Kimmerer (I love this book! It is a beautiful combination of stories and ancient wisdom that changes the way you see the world and our relationships to each other and the world.)

- Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates (in an open letter to his son, Coates paints a picture of race in the U.S.)

- All About Love and Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope, by bell hooks (she has a way of telling unflinching truths with love and openness)

- So You Want to Talk About Race, by Ijeoma Oluo (particularly about the racial landscape in the United States)

- Blind Spot: Hidden Biases of Good People, by Mahzarin R. Banaji and Anthony G. Greenwald (from the co-developers of the Implicit Association Test, a really useful test that you can take online to help you understand your own biases)

- Conflict is Not Abuse: Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility, and the Duty of Repair, by Sarah Schulman (I’m not sure I agree with everything in this book, but it was still really helpful in expanding my thinking about the possibilities for generative conflict)

- Connecting to our Ancestral Past: Healing through Family Constellations, Ceremony, and Ritual, by Francesca Mason Boring (I’ve been intrigued with family systems constellations for some time and was happy to find this Indigenous lens on the teachings)

- Whose Land is it Anyway? A Manual for Decolonization (this book just came out and I haven’t read it yet, but it looks helpful – you can download it for free)

Memoirs:

- When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir, by Patrisse Khan-Cullers and Asha Bandele (a powerful and personal story of how she became an activist)

- Fire Shut Up in My Bones, by Charles M. Blow (a gut-wrenching story of poverty and race)

- Gender Failure, by Rae Spoon & Ivan E. Coyote (what it’s like to be gender non-conforming)

- Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, by Roxane Gay (read anything by Roxane Gay – she’s a powerful writer)

- Unbowed, by Wangari Maathai (Nobel Prize winner who mobilized women to plant trees across Kenya)

- Mighty Be Our Powers: How Sisterhood, Prayer, and Sex Changed a Nation at War, by Leymah Gbowee (facing conflict in Liberia with creativity and strength)

- Confessions of a Fairy’s Daughter: Growing Up with a Gay Dad, by Alison Wearing (she also wrote Honeymoon in Purdah: An Iranian Journey, which I also really enjoyed)

- Living for Change: an Autobiography, by Grace Lee Boggs (an activist’s experience in Detroit)

- The Reason You Walk, by Wab Kinew (growing up with a father who’s a residential school survivor)

- A Long Way Gone: memoirs of a boy soldier, by Ishmael Beah (growing up in conflict in Sierra Leone)

- Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust, by Immaculate Ilibagiza (a powerful story of genocide)

- Laughing All the Way to the Mosque, humour/memoir by Zarqa Nawaz (a Canadian Muslim writer who wrote also created the sit-com Little Mosque on the Prairie)

- Between Two Worlds: Escape from Tyranny: Growing Up in the Shadow of Saddam

, by Zainab Salbi (the founder of Women for Women International, about what it was like to grow up with Saddam Hussein as a family friend)

, by Zainab Salbi (the founder of Women for Women International, about what it was like to grow up with Saddam Hussein as a family friend)

Poetry:

- Femme in Public, by Alok Vaid-Menon (powerful poems about being brown and gender non-conforming)

- Calling Down the Sky, by Rosanna Deerchild (about her mother’s experiences in residential school)

by Heather Plett | Jan 24, 2018 | grief, growth, holding space, Uncategorized

Two days before the end, I sat on a stool next to the armchair where Mom lay. When she leaned toward me, I leaned in too, afraid I’d miss what she’d say with her disappearing voice.

“I don’t know how to do this,” she said, looking at me with eyes that were searching but unfocused. My own words worked their way past a lump in my throat. “I don’t know how to do this either,” I said. And then we just sat there and breathed together, our foreheads nearly touching as we imagined this great gaping space in front of us that neither of us knew how to navigate.

She was soon to cross over into the afterlife. I was soon to cross over into the land of motherless daughters. Neither of us had any idea how we would make the journey. Neither of us had any advice or platitudes or ways of fixing this. Neither of us could offer to go on that journey with the other. All we had was this empty space… this liminal space… where we could sit together and fix our gaze upon each other and find an anchor in each other’s eyes.

Looking back over our 46 years together, that moment was quite possibly the most honest and sacred moment we ever shared. We had no expectations of each other. We had no reason to pretend we were anyone other than exactly who we were. There was no point in acting like we had wisdom or answers the other didn’t have, and no point in clinging to old hurts or misunderstandings that had never been (and would never be) resolved. All of that was stripped away and all we had was this moment… this meeting at the intersection of who we were and who we were about to become.

All we had was the space of “I don’t know.” And in that moment, it was the most painfully beautiful place to be.

I’ve come to believe that is the most potent space we can meet people in our relationships… the space of “I don’t know”. It’s the place where we shed our expectations and pretences. It’s the place where we reveal ourselves to each other and admit that much of what we think we know is simply smoke and mirrors. It’s the place where we seek no heroes or answers, where we ask only to be anchored by each other’s presence.

It’s the place where the true work of holding space can happen.

It’s not often that we find ourselves in this space with other people. It’s not often that we are both strong enough and vulnerable enough to offer that kind of space to each other. It goes against every instinct to protect ourselves and to prove ourselves. It takes effort and courage and a whole lot of trust. For those of us who’ve been wounded, marginalized, and oppressed, it’s even more difficult than for those who walk in the world with privilege and more assurance of safety. Perhaps, in fact, it’s the kind of space that some of us only enter in our final days on earth, when we have nothing left to lose.

Imagine, though, if more of our relationships found us in such a place. Imagine if you could trust people in your life to hold you and offer you an anchor no matter how much you’ve failed them or betrayed them in the past. Imagine if you could enter more conversations with people without having to posture and protect yourself.

We may never find perfection in our quest for this kind of space, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strive for it more often. I like to imagine, for example, what it would be like to intentionally seek to enter that kind of space when there are people working through conflict or reconciliation. What if, for example, those of us who are settlers in this country, could drop our baggage at the door and seek to show up with our Indigenous brothers and sisters in that kind of way, admitting that we don’t know what to do and showing our willingness to seek answers from the liminal space? And what if those who govern our country – our politicians – were willing to stop their posturing in order to sit in that space with each other, people from all sides of the political spectrum admitting that they don’t know the way forward but are willing to plant seeds for the future together? And what if we could do that with our own children? Or our parents? Or our communities?

Recently, my friend Beth and I have been practicing sitting in that space together. We have some parallel stories (ie. we’ve both recently ended a 20+ year marriage and we’re raising children around the same age). Plus we’ve both had an increasing awareness of our need, as settlers in Canada, to decolonize ourselves and we’ve had a recent experience together that heightened that awareness. In addition, we’ve been navigating some challenges in a community that is close to both of our hearts. So there is a liminal space element to both of our lives lately, as we evolve in the way in which we show up in our work, our families, and our communities.

Beth and I have long conversations over Zoom, where we just talk with little expectation of outcome or even clarity. One of us will text “can we circle up?” and we’ll find time to hold space for each other in a little virtual circle on our computer screens. Often our conversations end on a similar note as we began – still confused as to a way forward. In the middle of it, though, we each find an anchor with which to ground our wobbly selves.

We are meeting in the space of “I don’t know”. As we do so, we have to regularly renew our commitment and intention to keep laying down our pretences and instincts toward self-protection. This is not a natural space to be in with another person – it takes effort and humility. We want to impress each other, to prove our value, and we want to make sure we’re safe before we fully trust each other. We have to fight those inclinations in order to offer our vulnerability in such a space. We have too many stories of betrayed trust in the past to rush into an unguarded relationship like this.

I am lucky enough to have a few other friendships on similar journeys, and each one of them takes similar commitment and practice. The space of “I don’t know” can never be taken lightly – it is a great privilege that must be fostered and nurtured before it can grow into a plant that bears fruit. But once you taste of that fruit, you find yourself craving more and more of it, and relationships without it become less and less tolerable. And when you lose it, there is a deep grief and a hard journey back to that level of trust once again.

Sometimes I find it especially challenging to enter into this space because I am, in more and more of the spaces in which I find myself, a teacher/mentor/coach/facilitator who is expected to know things. People look to me with expectation and hope that I will help them find clarity and purpose, and I don’t want to let them down. I find myself becoming guarded sometimes, wanting to prove myself and not let people see me vulnerable. And yet… often it serves my students and clients well if I am willing to enter the space of “I don’t know” with them, to be humble enough to be in the learning with them, to show up willing to be shaped by our collective experience in the liminal space. (It’s a fine line to navigate and I don’t always get it right.)

The culture most of us live in has conditioned us to resist the space of “I don’t know.” Especially in North America (and I suspect in Europe as well, though my experience is limited), we have attempted to eradicate all chaos and insecurity from our culture. Out of our fear of uncertainty, we turn toward authoritarian leadership that, we believe, will keep us safe and always know how to make the path clear in front of us. We want assurances and safety and so we surround ourselves with people who look like us and talk like us. We resist the risk of engaging in spaces that make us feel like we don’t know what we’re doing, and so we marginalize those people who potentially bring that kind of risk into our lives.

But we can never live fully secure lives. We can never fully eradicate chaos. Every one of us will face illness, loss, death, and political instability. It’s simply a part of life. And the more we practice becoming comfortable in the space of “I don’t know” the more resilient we’ll become and the more expansive and beautiful our lives will be.

I believe (though I am far from an expert on such matters) that there are Indigenous cultures that understand how to navigate this space much more comfortably than those of us from European decent. Having sat in sweat lodges and other ceremonies and conversations with Indigenous people here and in other parts of the world, I have witnessed this invitation to sit in the liminal space, to release our baggage and false sense of our own importance. I have heard words spoken to me in Maori, Cree, and Choctaw that explain these concepts better than any English words I know.

As I learn to decolonize myself, I am learning how to receive the wisdom they have to offer without appropriating it or pretending I know something I’ve only recently begun to explore. Inherent in many of these traditions is a deep connection with the earth, which teaches us to be patient in the fallow seasons, to trust the unfurling or dying when the seasons shift, and to surrender ourselves to the mystery of it all. In New Zealand, for example, I was recently taught about the Maori concept of “a te wa” – “when the time is right” – that teaches us patience in the discomfort of waiting. I seek to trust the wisdom of “a te wa.”

In the liminal space, we need that kind of patience. We need the ceremonies and rituals that allow us to stay present for the discomfort. We need the teachers who can model how to stay present. And we need the relationships that anchor us there.

I don’t know how to fix much of the political mess in the world. I don’t know how to eradicate poverty or racism or prejudice of any kind. I don’t know how to help a friend whose life has been deeply altered by time spent in prison. I don’t know how to ensure that women can walk in the world without fearing sexual assault. I don’t know how to parent a child with the kind of anxiety I’ve never navigated in my life. I don’t know how to repair the damage when trust has been lost in a community. I don’t know how to navigate the world as a single mom when my children begin to move out of our home. I don’t know how to hold space for a friend or family member whose lives have suddenly been threatened by gang members. I don’t know how to repair the damage that has been done by settlers in my lineage who took what wasn’t theirs to take.

There are so many things I don’t know. And I don’t want you to give me the answers. I simply want you to meet me there… in the space of “I don’t know.”

* * * * *

Note: This is similar to the content I teach in my Holding Space Coach/Facilitator Program. The next offering starts in June 2018.

by Heather Plett | Dec 5, 2017 | grief, holding space, Uncategorized

“Wow. You’re the first psychiatrist to introduce himself to me,” I said to the man who stood in front of me with his hand outstretched. “The other two ignored me and never gave their names. I wondered if I had become invisible.” I reached out to shake his hand.

I’d been at my former husband’s bedside for a couple of days, waiting for them to move him from a bed in the emergency room to one in the psychiatric ward. I was worn out and fed up and didn’t have any energy left for niceties.

“That’s because they don’t want you to know who they are,” he said, the frustration in his voice echoing mine. “Everyone in this hospital is afraid of being held accountable for what they say and do, so they’re happiest if you forget them. Nobody wants to get sued or reprimanded for giving you bad advice, so we do only what’s necessary and no more.”

For the next twenty minutes, he unloaded his frustration on me. It was neither professional nor appropriate, given the fact that I was sitting at the bedside of a man who’d attempted suicide just days before, but it was the first time anyone in the hospital was speaking to me with any degree of authenticity or openheartedness, so I didn’t mind. With story after story, he told me of the deep disillusionment he felt, stuck in a system that made him doubt whether he was doing any good in the world. “We start out in this work because we have good hearts and we want to help people,” he said. “The system crushes that in a person. I decide to quit my job at least once a day.”

The next week in the psychiatric ward bore out the truth of what he’d said. It was a bleak environment, where staff followed the rules and did what they were told but had little heart left to provide real care for their patients.They took away my husband’s belt and shoe laces, locked the door behind him, and then mostly ignored him for the rest of the week. (I could come and go, but only when I was buzzed in.) Once a day (except on weekends), a psychiatrist would visit for about fifteen minutes a day for a brief conversation meant only to check whether the meds they’d prescribed were working, nothing more. Once, when I approached the psychiatrist assigned to him (when there was finally some consistency and not a new one every day) at the nurses’ station to ask whether there was more I could do to support my husband, he told me that our time was up and he wouldn’t talk to me. I’d have to wait until the next day.

I threatened to take my husband home or to find an alternate facility if there wasn’t more care or counselling offered to him. “If you take him home,” he said, coldly, “you do so against my advice and I will cut off his prescription.” I felt trapped. If I risked taking him home, he might have a relapse in front of our children, but if he stayed there, he might never lose that dead look in his eyes.

Desperate, I reached out to friends who worked in mental health and found a private psychologist who was willing to see my husband. I convinced the nursing staff my husband needed a “hall pass” for an afternoon (I’m not sure what excuse I made up, but I couldn’t tell the truth or I’d be accused of interfering with his care) and I snuck my husband out of the psych ward so that I could take him to see a psychologist.

That week tested every bit of strength and courage I had. During the day, I was fighting the system, serving as a fierce advocate for my husband. In the afternoons, I would drive away from the hospital weeping from the exhaustion, grief and fear of it all. Then, when I neared home, or my daughters’ school or the soccer field, I’d wipe away the tears, slip on an invisible mask, and become the supportive, strong mom my children needed. When other parents on the soccer field would ask where my husband was, I’d give some vague answer about a business trip or meetings. It wasn’t a safe enough environment for the truth. Changing the subject, I’d smile and make small talk and pretend that there was nothing more important to me in that moment than a soccer game. Then I’d drive home and feed my daughters, and when they were in bed, I’d muffle my screams and tears with my pillow. The next day, I’d do it all again.

I’m not sure why this memory came back to me recently, more than seven years after it happened, but I suppose there was still some residual grief and trauma stuck in my body that needed to be held for awhile. I’m not even sure what conclusions I want to draw from it for the purpose of this post, but I’m going with it anyway, because it reminds me of so many of the reasons why I keep believing this work I do, teaching people how to hold space for each other and for themselves, is so vital. Some days I’m tempted to go sit at the doors of that hospital to try to reach out to the spouses and daughters and parents who look the most terrified and say “if this hospital hurts you, come back and sit with me awhile”. Some days I want to lobby the health department to invest in my course or one like it for everyone in the system, starting with the leaders who decide how care is given.

When these memories started to resurface, I knew that it was time to extend special care to myself, letting myself shed some of the tears that got stuck in my throat, letting myself release the anger that I stuffed down in order to be a supportive mother and wife, and going for a good massage to release what’s still in my body. One thing I know for certain is that the work that I do in the world is only as good as the care I extend to myself. Unless I give myself time for healing and rest, I can not hold space for the healing of others. (That’s what the next few weeks will be about, as I replenish myself at the end of a very full year.)

As I reflect on this story, there are a few things that it continues to teach me:

- Good people with good intentions can have their hearts shrivelled up by systems that put rules and policies and fear of reprisal above compassion and humanity. What can we do about that? I don’t know if there’s a perfect answer, but I do know that some systems need to be dismantled, overhauled or abandoned, while others need new leadership that puts humanity before profit or rules. I have had very different hospital experiences (especially when I was in the hospital for three weeks before having my stillborn baby, when I encountered remarkable compassion and care), but in that particular situation, it seemed everyone I encountered, from the security guard who yelled at me for parking in the 15 minute zone when I was desperate to get my husband into emergency to the psychiatrists and nurses in the psych ward had become jaded and unfeeling.

- We can’t hold space for people if we let our fear of accountability get in the way of doing what we feel is best. This one goes pretty deep and is multi-layered. For one thing, this fear of accountability is systemic in a patriarchal, hierarchical, consumer-driven culture that is transactional rather than relational and that focuses on punitive rather than restorative justice. When the nurses in the psych ward took away my husband’s belt and shoelaces and locked the door, they were checking off all of the right boxes on the patient intake process, but they failed to look after his real needs. When the psychiatrists wouldn’t give their names, they’d lost touch with the reason they were in a helping profession.

- Holding space is an act of culture-making – it breaks the rules of the dominant culture and moves us into a deeper way of connecting.When we stay trapped in what is acceptable in the dominant culture, we lose our sense of community and compassion and we stay stuck in what Jung refers to as the “first half of life” where we see the world as binary and bound by rules and where we focus primarily on the needs of our own egos. In the “second half of life” we undo much of what was accomplished in the first half in order to get to a deeper heart of human life. We begin to see the many shades of grey rather than just the black and white. Systems, like the mental health care system that was my source of frustration, often get stuck in “first half of life” thinking and have a notoriously difficult time evolving because of their size and unwieldiness.

- Caregiver trauma needs more attention and acknowledgement.Though friends and family were as supportive as they could be, the bulk of the emotional labour of that week and the ones that followed were on me. And yet… not a single one of the professionals we spoke to that week paid any attention to how my husband’s suicide attempt was impacting me or how it felt to have his complex emotional needs and the needs of my children (who’d almost lost their dad) resting fully on my shoulders. (The same was true fifteen years earlier, the first time my husband attempted suicide.) I was an afterthought – not even given a few minutes at the nurses’ station when I was desperate for answers. Plus I had an internalized story of how I had to be the strong one and wasn’t allowed to fall apart. I didn’t seek therapeutic support until years later – hence the trauma that still shows up in my body now and then.

- You can’t tell what a person is holding when they’re making small talk on the sidelines of a soccer field. Every day, we encounter complex people with oceans of emotions hidden just under the surface. Some of them are so well practiced at hiding it all that they hardly remember that the emotions are there. Some of them are newly raw, with just a thin veil hiding what they don’t feel safe enough to reveal. If we keep this in mind, it helps us extend grace to the person who responds with more anger than seems warranted when the barista gets his coffee order wrong, or the person who runs away at the first hint of conflict. They may not want us to hold space for them in that moment (all I wanted from the other soccer parents was that they allow me to pretend everything was okay, not that they do or say anything that would crack me open at that moment), but they DO want our grace and patience.

If you want to know more about what it means to hold space, or you want to deepen your practice so that you don’t become jaded like the healthcare professionals I encountered, consider joining the Holding Space Coach/Facilitator Program that starts in January. There are only a few spots left – perhaps one of them is yours.

by Heather Plett | Aug 17, 2017 | Uncategorized

Everyone is talking about what happened in Charlottesville last weekend, but the problem with much of the response to this event is that it gives us a clear “them” to vilify. “Those horrible neo-nazis and white supremacists. Can you BELIEVE what they’re doing and saying?”

When we isolate them and their extremism, we miss the point that white supremacy is part of our culture and it’s something that ALL WHITE PEOPLE benefit from.

“The overtly racist White Supremacists marching in Virginia are not a part of a binary, they’re part of a scale. When we capitalize the words “White Supremacy” and treat it like a monstrous philosophy, it is an extreme that can be handily rejected by the majority of whites.

“However, on the same spectrum, less extreme, are the various forces that lead to the overrepresentation of whites in nearly every desirable facet of society, and to the contempt and distrust with which POC are seen. We have decided to call these things “white privilege,” but one rarely mentioned aspect of white privilege is the privilege to use language to pretend it isn’t white supremacy. Richard Spencer and his ilk are the id, not an aberration but rather a natural byproduct of unchecked white privilege.” From the article Why Privilege is White-Washed Supremacy.

If we all benefit from it, then we all must participate in dismantling it. This is not just a leadership problem (though good leadership would certainly make a difference). It’s not just an American problem (there’s lots of racism here in Canada too). It’s a problem that every one of us can participate in addressing.

Here are some things that you can do to help dismantle white supremacy. (Note: this list is meant primarily for white people and it emerges out of my own years of wrestling with my whiteness.)

1.) Do an inventory of how white your lens and life are. Do you surround yourself with white friends? Are your bookshelves full of books by white writers? Do you primarily watch TV shows and movies with white people in them? Are you doing business with, banking with, signing up for courses with, and hiring mostly white people? If so, ask yourself what you need to do to change the fact that you are centring whiteness.

2.) Listen to, read, and amplify the voices and wisdom of people of colour. Commit to reading only books written by people of colour for a year. Share at least one article each day on social media written by a person of colour. Sign up for courses with people of colour. Follow them on social media. If you have a public platform, share it regularly with voices that your audience needs to hear from.

3.) Buy from and amplify businesses owned by people of colour. You can do a lot of good by being more intentional about where you spend your money. Do your research and search out businesses owned by and run by people who look different from you. And then tell all of your friends about where you’re spending your money, not as a way of bragging about how socially conscious you are, but as a way of promoting these businesses and supporting their success.

4.) Consider the power of your vote. Do your research about the people you’re voting for. If you can, support people of colour running for political office (if they represent your political views). If the candidates in your neighbourhood are white, then at least talk to them about what they’re doing to address racism and white supremacy. Don’t just take their word for it – find out who they’re hiring, who they’re engaging in their campaigns, and who they’re doing business with for a better picture of how white their lens is.

5.) Talk to your racist neighbours, friends, family members, grocery store clerks, bus drivers, etc. Stand up for the people they dismiss. Challenge their attitudes. Invite them to multi-cultural events or lectures where they can expand their thinking. Don’t just ignore it because “they’re otherwise such kind people.” When you’re silent, you are complicit.

6.) Talk to the children in your life about racism and white supremacy. Point out the areas where they are benefiting from white privilege. Have hard conversations about news stories like Charlottesville. Model for them by letting them see you reading books by people of colour, having meaningful friendships with people of colour, voting for people of colour, and challenging your racist relatives. Help them develop strategies for addressing the racism they may be witnessing in their schools, sports teams, etc. (AND, when they grow up and start learning things you don’t know and listening to voices you haven’t heard, be willing to learn from them.)

7.) Research and send money to non-profits run by and working with communities that have suffered from oppression/colonization/conflict/etc. Non-profits that are run by white people, that have mostly white people on the board and on staff, etc. may be upholding white supremacy by not including the voices, wisdom, abilities, etc. of the people they say they’re serving. Note: I specifically said “send money”, because if you choose to send them the physical items YOU THINK they need, then you are taking their autonomy away. Unless they ask for specific items, let them make their own decisions by giving them money to spend as THEY see fit.

8.) Stop spiritual bypassing or other avoidance techniques and dare to peer into the shadow side of our culture. If you believe in “love and light” than dare to shine that light into the darkness of racism and white supremacy rather than trying to pretend that “we are all one race” or “I don’t see colour”. The fact that you have the option to avoid this kind of negativity is a sign of your privilege. Your spirituality is selfish if it lets you “rise above” the ugliness of the world.

9.) Learn to sit with discomfort. Do the personal work (mindfulness, therapy, coaching, etc.) that will build your resilience and help you deal with negative emotions in a more healthy way. If you are always running away from fear, shame, anxiety, etc. then you won’t have the courage to step into difficult conversations where you might be challenged for your white privilege, covert racism, etc. If you shut down every time someone expresses an opinion different from yours, then you’ll stay in your little bubble and not contribute to the change this world needs.

10.) Find places for conversations and meaningful action. Join an ally group that supports the causes of people of colour (eg. SURJ). Start a conversation circle where you can wrestle with the hard conversations. Seek out Facebook groups or other social media forums. DON’T rush in to do what YOU think needs to be done – instead, follow the leadership of the people most impacted by the issue and LISTEN.

by Heather Plett | Aug 14, 2017 | Uncategorized

The border appeared too quickly. On a small highway with little traffic, nobody had bothered to post a “5 km to the U.S. border” sign, so I was suddenly there with no time to prepare. With some trepidation, I pulled up next to the border guard’s window, took off my sunglasses, smiled my best “I’m not a danger to your country” smile, handed him my passport, and tried not to look nervous.

I could feel my heartbeat increase as he scanned his computer. Would he see the alleged “note on my file” that the last border guard had said he was putting there when I’d been told I didn’t have the right visa and wouldn’t be allowed back into the country without it? Would he turn me around and send me back home, even though I was visiting for pleasure this time and nobody would be paying me to work in the country? Would he, like the last border guard, wave a binder full of visa information in front of me and say “I’m not sure which visa you need, but I know you don’t have it.” I wasn’t sure… all I could do was smile, nod, and cooperate when he peered through my car windows at the camping equipment in the back.

Minutes later, he’d let me through without incident. My body reacted with relief, taking deep gulps of air to fill the lungs I’d apparently been depriving. How long had I been holding my breath waiting for this moment? Perhaps for months already.

I didn’t realize, until that moment, just how claustrophobic I’d been feeling, worried that I might no longer have easy access into the United States where so many of my friends, colleagues, and clients live. Many people live rich and full lives without ever owning a passport or crossing an international border, but I am not one of those people. I was born for expansiveness, for global wandering, for deep connections with people and places all over the world. A smaller life than that leaves me feeling trapped, with less air to breathe. (Yes, I am aware of what a privilege this life is, and how my normal privilege, as a white woman, is to easily cross the border into any country I’ve visited.)

After my breath slowed and I continued my long drive to the Boundary Waters for my canoe trip, I had a sudden flash of insight…

I have been performing for border guards all of my life, waiting anxiously with a smile on my face as they decide my fate, hoping I haven’t done or said anything that might offend them or turn them against me.

Every woman knows this story. So does every person of colour, LGBTQ+, disabled person, and member of other oppressed groups without access to power. We all know that we can choose to stay in our own “countries” (the spaces, jobs, neighbourhoods, etc., where those with power consider to be our rightful place). But if we dare to venture forth into more expansive “countries”, we have to face the border guards who have the power to create or dig up arbitrary rules about why we don’t belong there.

There were the border guards who told me which sports a girl was allowed to play. And some who told me what clothing was acceptable and wouldn’t create too much temptation for the occupants of the more powerful “country”. Others who said that I was pretty smart “for a girl”, letting me know that there was a limit on how far I could go with my intellect. And there were those who didn’t allow me into certain boardrooms or didn’t invite me to attend political events because I didn’t play “the (male) game” well enough. And some who told me I couldn’t be a good leader if I didn’t learn to keep my emotions out of it. And some who said that women weren’t as valuable in the workplace because they’d end up going off on maternity leave at some point. And others who implied that the business I longed to build was too “soft” to be taken seriously.

Most of those border guards didn’t think of themselves as border guards and were probably never fully aware of the fact that they were keeping me or anyone else out of their country. They simply saw it as their birthright to live in a more expansive country than I did, and when they saw me or anyone else trying to cross the border, they got nervous that there wouldn’t be enough space for all of us, so they pushed back, made up arbitrary rules, and protected their territory. Some were probably very uncomfortable enforcing these arbitrary rules, but they feared they’d be kicked out of their own country if they didn’t uphold them. (I think of my father, for example, who admired strong women and often told me so, but, as the leader of our small church, couldn’t let me do Bible reading or speaking from the pulpit because it would make other church members uncomfortable.)

Just like I could choose to stay in Canada, I could choose to build a relatively full and happy life within the confines of this country called womanhood, but that’s not the life I was born for. I was born with natural gifts in leadership and communication – both things I’ve often been told I’d need to suppress in myself because of my gender. The claustrophobia that had me holding my breath at the border had me holding my breath on a regular basis when I feared I’d reached the limits of what’s acceptable for my gender.

There’s another claustrophobia that I’ve wrestled with in my past and that is the claustrophobia of the faith I was raised with. There are many things I love about my Mennonite roots, but the “evangelical” part is one that my expansive heart wouldn’t let me hang onto.

I could no longer live within the confines of a “country” where we were taught that there was only one way to get across the border – to have access to the “true God” and to get the golden ticket to heaven. I could no longer live in a country where my Muslim friends, my Hindu friends, and my LGBTQ+ friends needed to be converted. I couldn’t be part of a faith that wanted me to become one of those border guards, letting people know how to gain access.

Once again, I don’t think anyone within the evangelical faith tradition thinks of themselves as border guards and some will be offended that I offer this analogy. The people I know well are loving and kind people who want to share the faith that sustains them and I don’t blame them for that – faith is a good thing to have and to share. But I know that my own personal claustrophobia only ended when I chose, instead of an evangelical church, to sit in circles with other seekers who choose not to believe that one way is the only way, that one “country” is the only good country.

In both of the situations I’ve mentioned, I learned, to one degree or another, both to live with my claustrophobia and to begin to serve as a border guard myself, conveying the rules to those who didn’t yet know them, letting some people know that they weren’t behaving in a way that warranted access, and protecting the privilege and power that I, too, have benefited from. When it comes to being white, for example, it served me well to work with the border guards in making sure we didn’t have to share the country of power and privilege with too many others. Sometimes, serving as a border guard is as simple as turning a blind eye to the plight of those who’ve been denied access.

I kept myself small too, serving as my own border guard and limiting myself with my own self-doubt, fears, and internalized oppression. It was easier to learn to live with the claustrophobia than to risk the judgement of the border guards I was taught to fear.

This week, I looked at the photos of the white supremacists marching with torches in Charlottesville and I saw border guards. These young white men desperately want to protect the “country” that they believe is their birthright. The world is changing around them and they feel threatened and backed into the corner by those people demanding access to what they’ve always assumed belonged exclusively to them. They watch the rise of Black Lives Matter, the Women’s March, the election of a black president, increased immigration, and the legalization of same sex marriage, and they’re incensed with the fact that too many people are crowding into their “country”.

But the thing about being a border guard is that it’s a fear-based position. If you are tasked with protecting something that everyone else wants access to, you have to be ever vigilant and watchful and you can’t help but be somewhat paranoid. You can’t really trust anyone because you never know when they might threaten what you want. And you have to be willing to sell your soul for the cause of the country you’ve pledged allegiance to. When the rules change, you have to keep enforcing them even if you don’t understand or agree with them. One false move and you could lose your precarious position, so you learn to obey the masters that control your fate and dole out the power you’ve become addicted to.

Just like there is claustrophobia in being confined to a country that feels too small for you, there is claustrophobia in being a border guard protecting a space that outsiders are trying to get access to. I could see that claustrophobia on the faces of those young white supremacists. Their coveted space is getting smaller and they’re panicking over the fear that sharing it means less for them. Their wide open spaces don’t feel so wide open anymore.

I don’t only suffer from claustrophobia in a metaphorical sense – I face it in a very real sense in closed, crowded spaces. When it happens, I have a minor panic attack and have to find a quick exit to an open space where I can take deep gulps of air, just as I did when I crossed the border last week.

I’m sure some of those young white supremacists were feeling a similar desperate need for the fresh air they’ve convinced themselves they no longer have access to, and they’re willing to step on people in their desperation to get to it. If they only knew that the only way to breathe truly fresh air without feeling like you’re being closed in on is to allow everyone to breathe that air.

I don’t know for certain if this was the origin of my claustrophobia, but this is the first of it I remember… My older brothers and their friends had constructed an elaborate maze out of hay bales. As kids on the farm, we often built forts in the hay bales, but this was the first time I remember them building a maze, where you enter a dark, narrow doorway on your hands and knees and have to find your way to the exit, feeling your way along in the pitch black. Since you’re in a space only big enough for your body on hands and knees, there is no turning back.

I was always eager to hang out with my brothers, so I accepted their invitation to be the inaugural visitor to the maze. Once inside, I panicked. No matter where I turned, I couldn’t find the light at the end of the tunnel. The walls started closing in on me. I called to my brothers to let me out, but, at first, they laughed and said I’d have to keep trying. Then I started to panic, shrieking and flailing, desperate for light and fresh air, convinced I was going to die inside that dark tunnel. Finally, my brothers, who cared too much for me to leave me trapped, began dismantling the maze until they found me and could release me into the fresh air.

This isn’t just a story from my childhood – it’s a metaphor for what we need to consider in our culture right now. There are people trapped inside the maze of patriarchy and white supremacy, trying to get access to the same air that those outside the maze have access to. (Think, for a moment, of Eric Garner, who died telling the police “I can’t breathe!”) There are people who’ve reached the height of their claustrophobia and they’re flailing around and screaming, trying to get the attention of the people on the outside. Those who stand outside can choose to hang onto their fear that there is not enough air for all of us and continue to serve as border guards, serving the system they created and benefit from, or they can start to dismantle the system, one hay bale at a time.

I choose to be one of the dismantlers.

Because the air I breathe is only fresh if you have access to it too.

by Heather Plett | Jun 14, 2017 | Uncategorized

I am fat. Let’s get that out of the way first. At least 60-70 pounds over what would be considered my “ideal weight”. Probably more, but I don’t own a scale.

I don’t love this about myself, but it’s part of my story. It has been, to varying degrees, all of my adult life.

Yes, there are reasons why I am fat. Maybe it’s thyroid related. Maybe it’s trauma related. Maybe it’s far too much self-soothing with food. Maybe it’s the way I always found it easier to value my brain over my body. Maybe it’s the religious shame that told me my body is a sin. Maybe it’s about me trying to protect myself from being raped again. Maybe it’s the pussy grabbing. Maybe it’s a lifelong battle against a patriarchal world that wants to label me, shame me, and force my body to conform. Maybe it’s all of those things.

Whatever it is, it’s my story. It’s the most visible story because I carry it with me every single day, but it’s also the hardest to talk about. It carries the most shame and fear of judgement, not because I think I’m bad or ugly or don’t love myself (I do), but because fat is one of the most unacceptable things to be in this image-obsessed world. It’s one of the hardest to live with, because there is always the assumption that it is “your fault”.

I’ve done enough public story-sharing to know that there will inevitably be those people who will read my story and judge me and/or want to fix me and send me the right diet, the right thyroid cure, the right books, the right self-love teachings, the right exercise plan, etc. They’ll tell themselves they’re doing it with my best interests at heart (don’t I want to live a long life? don’t I want to be a good influence for my children?), but they’re really not. They’re doing it because of their own discomfort with fatness.

And so I keep my fat stories close to my chest.

But this week, thanks to Roxane Gay, I feel differently. I feel like I want to add my voice to hers and say “We’re fat. Get over it.”

“Fat is not an insult. It is a descriptor. And when you interpret it as an insult, you reveal yourself and what you fear most.” – RG

Roxane Gay wrote a book called Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body. I haven’t read it yet, but it’s high on my list of “must read soon”. In it she shares what it’s like to walk around in the world as a fat person.

Coming out with her story should be liberating and empowering for Roxane (and I hope it is, for the most part) but this week, she was fat-shamed by one of the interviewers who talked to her about the book. Mia Freedman introduced the podcast by talking about the detailed preparations that had to be made for Roxanne Gay to visit her recording studio. “Will she fit into the office lift? How many steps will she have to take to get to the interview? Is there a comfortable chair that will accommodate her six-foot-three, ‘super-morbidly obese’ frame?”

The article made my blood boil. An interviewer should be honoured and humbled that someone of Roxane Gay’s stature (and by that I don’t mean size) and wisdom would visit the program. She’s one of the finest writers I know of and the fact that she is willing to share her vulnerable stories with people should be seen as a gift beyond measure. To shame someone who has done that kind of emotional labour on other people’s behalf is unconscionable and downright disgusting.

I was angry, but I was also triggered. I haven’t been the target of such overt and public fat-shaming, but I know what it’s like to have people look at you funny if you dare to eat french fries in public. And I know how it feels to have people on planes glance at you with a look that says they’re hoping they’re not seated next to you. And I know what it’s like to be hesitant to ride your bicycle around the neighbourhood because you’re pretty sure people are judging you.

Here’s a newsflash in case this comes as a surprise… Fat people know they’re fat. And we don’t need pity or advice or judgement. And there is absolutely nothing a stranger could say to us that would suddenly make us able to change the size of our bodies. Every piece of advice on getting thinner is already available to us. Every bit of shame anyone’s tempted to heap on us, we’ve probably already heaped on ourselves.

We’re not fat because we’re not smart enough, don’t try hard enough, or haven’t been shamed enough for it. We’re fat because… well, because we’re fat. That’s about all anyone other then us and perhaps our most intimate circle of friends, family, or medical professionals (if we so choose) needs to know about us.

We might choose, like Roxane Gay, to offer up a story to help people understand why we’re fat, but we do not owe that story to anyone. When we choose to be vulnerable about it, that is our gift, not our obligation.

After reading the story about Mia Freedman, I watched an interview Roxane Gay did with Trevor Noah. In it she talked about how her weight started accumulating after she was gang-raped as a young teenager. And then she said something profound that goes beyond just a story about weight.

“People want a triumphant narrative. They want to know that you have solved the problem of your body. But my body is not a problem and it’s certainly not something I have solved yet.”

Indeed. We want the triumphant narrative. We want to hear stories of success – of how a simple diet or lifestyle change transformed someone’s life – so that we can believe that success is possible and there are neat bows that can be tied around a story to clean up the messy bits in the middle.

But we don’t always get the triumphant narrative. Sometimes we get continued struggle. And sometimes we get to a place of acceptance of what is rather than a triumph over it.

I have been struggling with that triumphant narrative this past year. Though I didn’t know it consciously, I had subconsciously bought into the typical health and wellness coaching narrative that leads us to believe that when we find contentment and healing in our lives and once we get rid of the external baggage that was weighing us down, we’ll start to lose pounds off our bodies as well. “Clear out the bad energy and your body will respond accordingly.”

I’m the happiest and healthiest I’ve been in a long time. A LOT has shifted for me emotionally in the two years since my marriage ended. I got rid of a lot of clutter (both physical and emotional) when I cleaned out and renovated my home. My business has grown and I’m doing work that I love and that I’m fulfilled by. I’ve been for therapy and I’ve done lots of energy and body healing work. I’m learning to pay attention to my body in new ways. I’m in such a good place, I almost feel guilty sometimes about how good my life is.

But… I am also the heaviest I’ve ever been. Heavier than I was when I was pregnant with my daughters. And that doesn’t make sense in a world that wants a triumphant narrative.

There’s a part of me that doesn’t know how to square that away in my mind. Shouldn’t all of that effort to heal my emotional wounds result in a slimmer body? If I gained the weight because of the trauma and wounds, shouldn’t it come off now?

But there’s another part of me – the part that has sat at the bedside and watched my mother die, the part that held my dead son’s body in my arms, and the part that knows that rapists climb through windows – that knows that the triumphant narrative is, more often than not, bull shit.

Sure we get triumph sometimes, but we also get pain and failure.

Perhaps the direct correlation between the healing and the weight loss is just another one of those marketing stories the health coaches want to sell us. Maybe it’s a lot more complicated than that. Otherwise… wouldn’t Oprah, with all of her experts and money, have figured out how to keep it all off permanently by now?

What I keep coming back to is this… Acceptance and resilience are worth a lot more than triumph.

Sure, triumph is flashy and alluring, but acceptance and resilience are a lot more valuable in the long run. Acceptance and resilience bring contentment and teach us how to get through the fire the next time it comes.

That’s the part I’m working on. I am accepting this fat body that still loves to ride a bicycle through the neighbourhood. I am accepting the amazing way this body knows how to birth babies even when they’re dead. I am accepting the pain this body is capable of holding. I am accepting the fact that this body loves pleasure and comfort and good food and good wine. I am accepting the way it feels when my beloveds wrap their arms around this body. And I am accepting the fact that there are still emotional wounds that this body is holding that may take all of my life to heal.

Because this body may be fat, but this body is also powerful and fierce and has climbed mountains, wielded hammers, birthed babies, carried canoes, held crying children, hiked through forests, slept on the bare ground, skinny-dipped in wild lakes, made love, survived rape, and rode horses.

And this body will continue to do all those things for as long as she can no matter how much judgement comes her way.

, by Zainab Salbi (the founder of Women for Women International, about what it was like to grow up with Saddam Hussein as a family friend)