by Heather Plett | Mar 1, 2013 | circle, Community, Leadership, Passion

I didn’t know how much launching Lead with your Wild Heart would change my life and my business, but it has, dramatically. Interviewing the incredible members of my wisdom circle, researching, writing, and teaching this program have taught me more than any course I’ve ever taken or ever created.

In shamanic language, this feels like my original medicine – the gift I’m meant to contribute for the healing of the world. In helping women (and, in the future, possibly men) get closer to their wild hearts, I am becoming intimately familiar with my own. (The next offering will begin in May, and I expect there will be in-person offerings to come as well.)

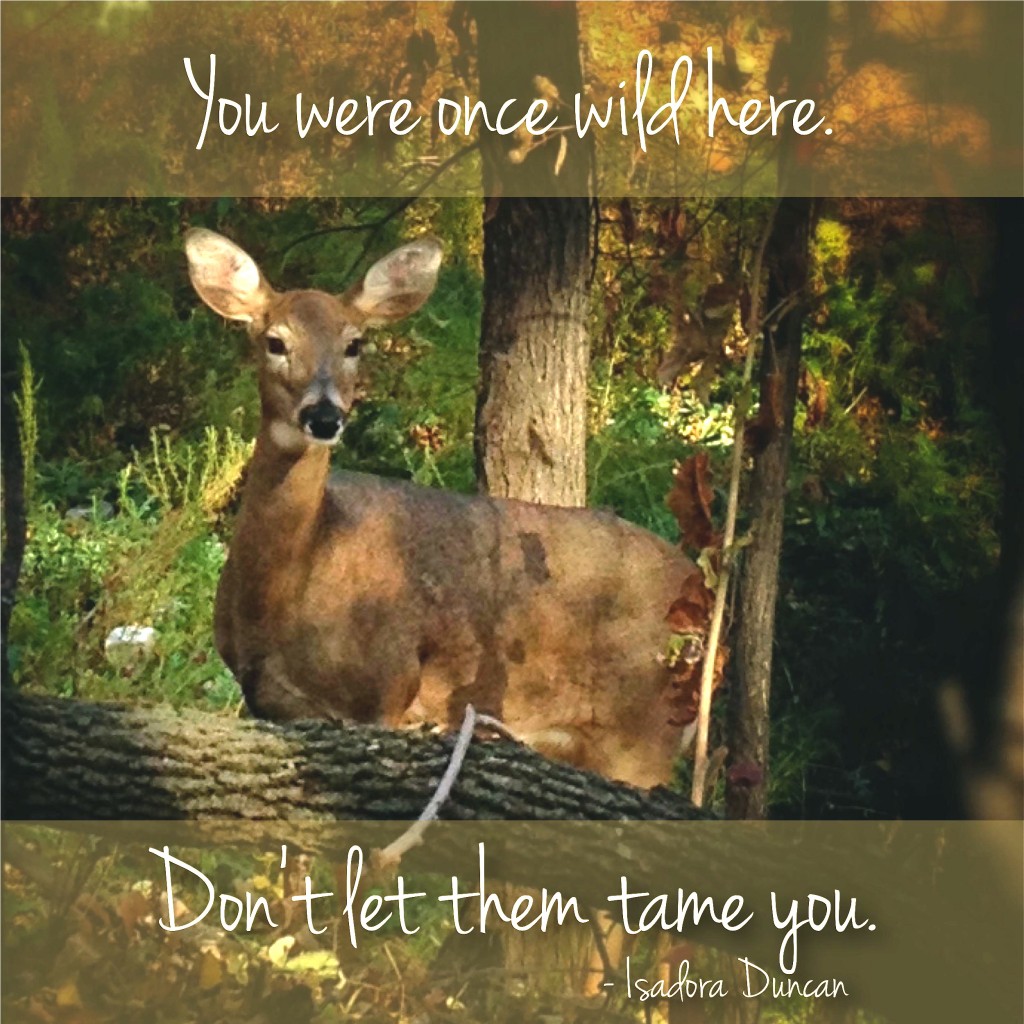

The seeds for this course came to me one day last summer when I was wandering in my favourite woods. There are often deer in those woods, and I have such great reverence for deer that I always stop to pay attention when I see them there. Often I follow them deeper into the woods.

One particular time, I almost missed the deer that was standing completely motionless about ten feet from the path on which I walked. The deer was watching me, and when I stopped on the path, we stood locked in a visual embrace for what I think was about ten minutes but what felt like an eternity.

I walked away from that encounter with the profound sense that the deer needed me to understand something that I’d been missing before. Further along the path, it came to me. “I need to create a program called Lead with your Wild Heart. I need to teach women how to get reconnected again.”

The deer invited me back into the wild – back to my wild-hearted trust, wild-hearted love, and wild-hearted courage. Those are the things I now share with the incredible circle of women who have gathered for this program.

Sometimes my coaching clients lament that they are not very good at planning or goal-setting, and I tell them “Maybe you don’t have to be. Maybe you just need to be good at wandering in the woods and listening for the wisdom.” You won’t hear that in business school, but my best ideas have almost always emerged when I’ve found time to be silent in nature.

The deeper I go in this journey, the more I understand what it means to be wild again.

To be wild again means that:

- We are connected with the earth, the wind, the deer, and the trees.

- We are connected with each other in a deeper way than our culture encourages.

- We trust that which is primal and wild in ourselves and we offer our most natural gifts to each other.

- We trust that which is primal and wild around us and we honour the wisdom of creation.

- We remember that we are stewards and citizens rather than consumers and conquerors of this earth.

- We dare to weep when we are wounded, laugh when we are joyous, and touch when we are in need of each together.

- We reclaim the circle and gather around the fire, sharing our most vulnerable, wild stories.

- We dare to plunge the depths of our wild hearts and honour what we find there.

- We sing and dance, trusting both our voices and our bodies to be expressions of the sacred.

- We are courageous warriors, serving the cause of all that is good in the world.

- We dare to believe that the world is a good place to call home.

by Heather Plett | Feb 6, 2013 | change, circle, Creativity, Leadership, women

I have the great privilege these days of co-hosting a women’s leadership program that meets every second week in a small town an hour and a half from the city where I live. There are so many things about this that I love, including the fact that I have a regular reason to drive out into the country and see the wide open prairies and the wild, alluring woods. With no parents left to visit, I don’t get out to my rural roots often enough to suit me.

On the drive out there yesterday, we had a rare and wonderful sighting of a lynx as it dashed across the road and ran off into the snowy woods. It felt like a moment of blessing.

Yesterday’s session focused on facilitating change. The best change process I know of is Theory U, a process I was first immersed in at ALIA Summer Institute and that I’ve been a dedicated student of since.

I introduced the idea of a Change Lab, where-in we would walk through the U process by casting ourselves in the role of community leaders who recognize the need for change in how the community is organized.

I started out by sharing the story of Baba Yaga’s House in Paris, France, a home created for aging feminists by a circle of women who realized that none of the available models for seniors’ housing fit with their values or expectations of how they wanted to live. (I encourage you to listen to the podcast at the link above.) “Imagine we are these women,” I said. “We are faced with an established community model we know doesn’t work for us, and yet we haven’t found a new model that we’re comfortable with.”

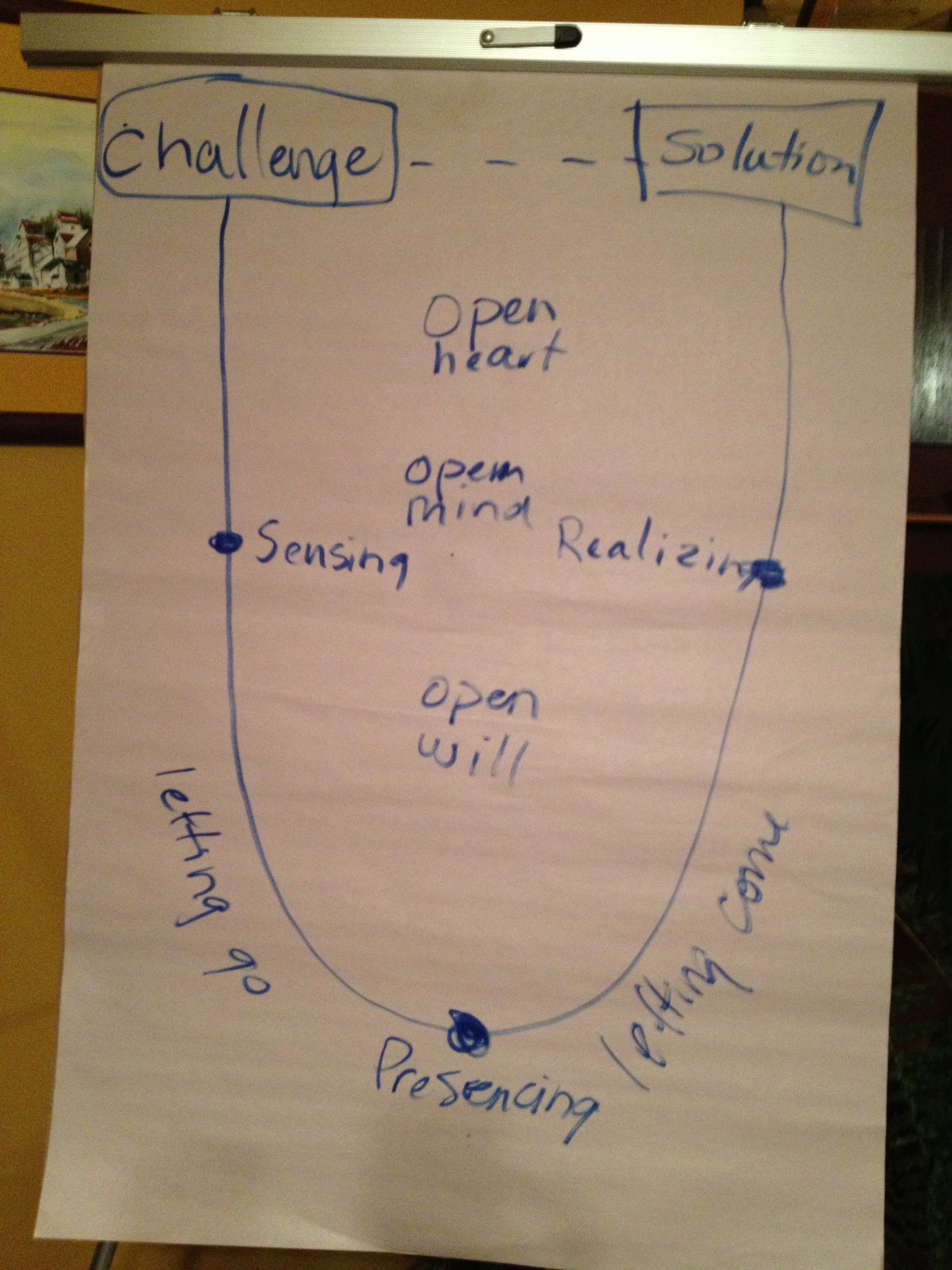

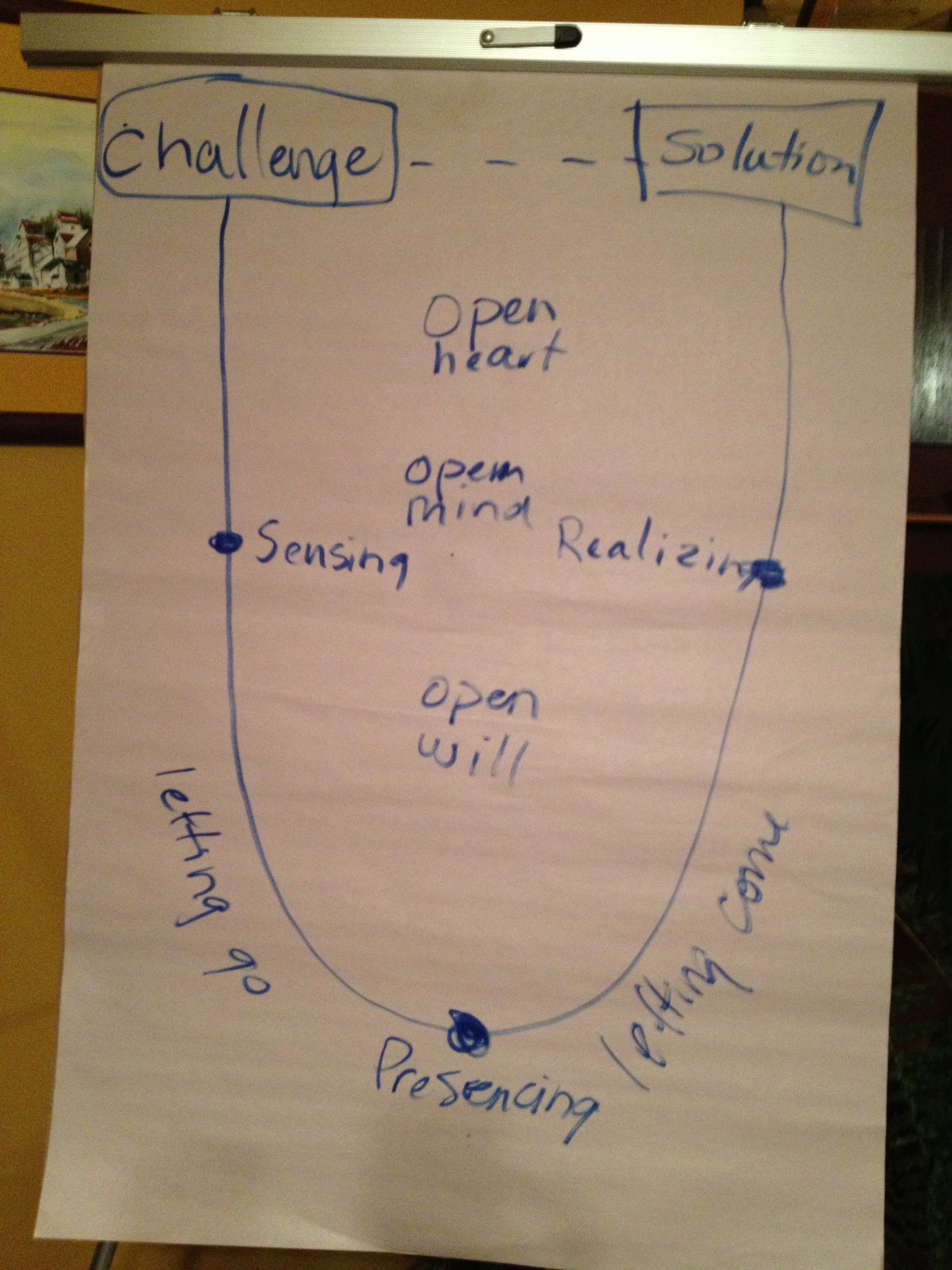

From there I moved on to an explanation of Theory U, a method for co-creating social change. Instead of trying to find a direct route from challenge to solution – the way some of the more linear models do, with brainstorming, strategic planning, etc. – Theory U takes us on a deep dive into the unknown. Instead of trying to direct change, we host what is wanting to be born. Instead of trying to control, we let go and let come. Instead of expecting the future to look like the past with just a few tweaks, we invite a new future to spiral up out of the brokenness of the past.

In Theory U there are three main parts – sensing, presencing and realizing. In the sensing phase, we are invited to use all of our senses to witness what is present. We are invited to suspend our judgements, opinions, assumptions and mental models, and to use our eyes and ears and the feeling of our bodies to sense into whatever the context is. We host conversations, we ask good questions, we listen deeply, we watch with full attention, and we notice how our bodies feel.

In Theory U there are three main parts – sensing, presencing and realizing. In the sensing phase, we are invited to use all of our senses to witness what is present. We are invited to suspend our judgements, opinions, assumptions and mental models, and to use our eyes and ears and the feeling of our bodies to sense into whatever the context is. We host conversations, we ask good questions, we listen deeply, we watch with full attention, and we notice how our bodies feel.

In the presencing phase, we are invited into the inner work of grounding ourselves in our bodies and paying attention to what is emerging. We listen into the space and learn from the future as it emerges, letting go of our expertise and experience. Rather than moving directly into problem solving or brainstorming, we take time for retreat and reflection. The best place for presencing is outside in nature where we ground ourselves in the earth and lean into the trees.

The third phase is Realizing. In this phase – on the upward movement out of the U – we “let come” what wants to emerge. We bring insights, sparks of inspiration, and crystals of ideas into prototypes. We move into action quickly and create small projects that can move the vision forward.

When I introduced Theory U to a women’s circle in Ontario last year, someone pointed out that I’d just drawn a woman’s breast. She said it with laughter, but when we started to unpack that, we realize that there was resonant truth to what she witnessed. This process definitely has a feminine aspect to it (as is laid out in this article by Arawana Hayashi) and it relates well to an infant suckling at the source of his/her life. It’s about going back to Source, it’s about seeking nurturing and rebirth, and it’s about the kind of rest and retreat that a mother must seek every few hours when an infant needs to suckle. It’s about being innocent, vulnerable, uneducated, without judgement, and open to a new future, just like that tiny baby. Since that first observation, I’ve brought up the idea every time I introduce it, and it always opens up interesting dialogue.

Once I had introduced the Theory, it was time to move into practice. To start with, I did one of my favourite things to do in workshops – I dumped a pile of garbage on the floor (things I’d gathered from my household recycling bin). “This,” I said, “represents the chaos and brokenness of the systems that no longer work for us. Out of this, something new wants to emerge, but we don’t yet know what it is. It will be up to us to host that new thing into being, without relying on what was or casting judgement on the ‘way it’s supposed to be’.”

In the Sensing phase, I asked them to sit in one-on-one conversations with a few different people in the room. “Ask deep questions, explore what is present, and use your senses to witness what is. Suspend judgement and don’t rely on past or second-hand information.”

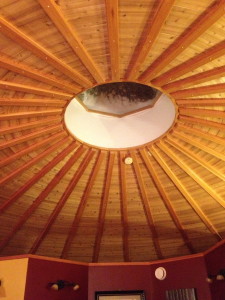

After a few rounds of conversation (too short, but all the time we had), they were invited to move into Presencing. “If it weren’t a cold winter night outside,” I said, “I’d encourage you to move outside for this part. Instead, find a quiet place inside where you can be alone with your thoughts and with whatever wants to emerge.” (As an aside, it felt beautifully appropriate that we were gathered inside a mandala home, a circular home built with great intention around honouring the four directions, giving space at the centre, and blending into the beauty of nature that surrounds it.)

After a few rounds of conversation (too short, but all the time we had), they were invited to move into Presencing. “If it weren’t a cold winter night outside,” I said, “I’d encourage you to move outside for this part. Instead, find a quiet place inside where you can be alone with your thoughts and with whatever wants to emerge.” (As an aside, it felt beautifully appropriate that we were gathered inside a mandala home, a circular home built with great intention around honouring the four directions, giving space at the centre, and blending into the beauty of nature that surrounds it.)

The next phase brought them back to the garbage on the floor, where they began to explore what wanted to emerge. Some felt stuck and really didn’t connect right away with the garbage on the floor. Others were eager to jump in and host the emerging future. Before long, though, everyone had made a valuable contribution to the scale model of the new community that wanted to be born.

We spread our community out on a large piece of cardboard on the table. Some pieces represented a connection with nature, others represented a connection with our neighbours, others represented a connection with opportunities/arts/beauty/etc., and still others represented a deeper connection with self and the sacred.

When we sat discussing the panorama in front of us, we realized that the resounding theme of what was emerging was connection. We were all longing for connection – with each other, with the earth, with the water, with the Sacred, and with ourselves.

One woman asked “If recycling is the bi-product of a culture of consumption, what can replace consumption as our dominant paradigm that will no longer have a requirement for recycling?” Connection, we agreed. We need deeper connection.

One woman asked “If recycling is the bi-product of a culture of consumption, what can replace consumption as our dominant paradigm that will no longer have a requirement for recycling?” Connection, we agreed. We need deeper connection.

Before we departed for the night, I invited the women to consider (in their private moments, when they were back in their homes) “How might each of us be ambassadors for connection in our communities? How might we begin to invite this future into the circles in which we live?”

The women left with new lights in their eyes that hadn’t been there when they’d entered the room – all because of a pile of garbage and a time of connection.

(Next week’s session flows beautifully out of this… We’ll be talking about making connections in women’s leadership circles, using the new toolkit created by my teachers Christina Baldwin, Ann Linnea, and Margaret Wheatley.)

Note: If you want more inspiration on this, visit Presencing Institute, read Theory U, Presencing, or Walk Out Walk On.

by Heather Plett | Jan 23, 2013 | circle

I’ve taken on the delightful task of co-hosting a women’s leadership learning circle that meets every second Tuesday in a rural community in our province. Yesterday’s circle focused on conflict resolution and difficult conversations.

We started the evening making collages that represented the things that we want to breathe out (release/stop doing) and breathe in (receive/embrace/learn) in relation to conflict in our lives. From there we moved into personal assessments of how we each respond to conflict. We talked about how each conflict is shaped by our level of commitment to the relationship and to the agenda at stake, and how we choose our conflict styles accordingly. The sharing in the circle was, as always, personal and intimate. There were stories of conflict in our workplaces, conflict in our marriages and family relationships, and conflict within ourselves.

At the end of the workshop, we asked the women to share what they had breathed in (received) and what they had been able to breathe out (release) throughout the course of the workshop. As they shared, we passed around a talking piece – the courage stone that was a gift from my friend Jo-Anne.

When the stone had completed the circle and returned to me, I said “it is always a pleasure to hold this stone after it has been in the hands of each of you in the circle. As it passes around the circle, it picks up energy from each of you, and that energy changes the rock. The colour becomes richer, and by the time it gets back to me, it is much warmer than it was when I first pulled it out of my bag. You have each given a piece of your energy to this circle and to this stone.”

Women’s circles are always the same. We bring little bits of courage, little bits of fear, little pieces of our stories, and little bits of our love. We pour it all into the container of the circle, we hold the edge for each other, and our offerings lend each of us a little bit more energy and courage than we put in.

It’s like a soup for which we each brought an ingredient. You may have only brought the carrots, but once the soup is done, once we’ve each had a chance to add our ingredients, we each have enough for a nourishing meal.

As we pass our stories around the circle, our courage grows and we all leave changed by the time we spent together.

by Heather Plett | Dec 4, 2012 | beauty

The woodpecker that visited Mom's feeder shortly after she died, photo by my sister Cynthia

In the last few months of her life, Mom spent a lot of time watching birds. I often sat and watched with her, marvelling at the variety that came to visit. We don’t have much of a history of bird-watching in our family, but we do have a history of paying attention to nature. One of the things that came up at Mom’s funeral was that whenever she went on road trips, she always hoped she’d be the first to spot wild animals. I’ve always been the same.

On one of our last visits, my sister and I spotted a large bald eagle perched in a tree not far from Mom’s house. It’s unusual to see bald eagles where we live, so it seemed an omen of sorts – perhaps bearing a message that our lives were about to change.

Two weeks ago, I brought a new bird book to Mom’s house, hoping we’d get to spend many hours leafing through the pages, trying to identify the birds that visit. Mom never looked at it. That was the day she began slipping away.

The next day, I was teaching at the university, but probably didn’t communicate much through my distraction. I kept my cell phone close, knowing I could get a call at any minute. At noon, after hearing from my brother that her health had declined quickly in the last 24 hours, my sister and I rushed out to be with her.

Before going, though, I made a quick trip to the bookstore. My friend Barbara had mentioned the book When Women Were Birds, by Terry Tempest Williams, and I knew that I had to have it. It’s a collection of short pieces on voice that Williams wrote after her own mother died. I tucked it into my purse.

Mom’s health declined so quickly that day that we were certain she would not live until morning. Her strength disappeared, her voice reduced to a whisper, her mind started slipping away, and she stopped eating and drinking. My siblings (two brothers and a sister) and my mom’s husband all sat with her, comforting her, singing hymns, reading her favourite Bible passages, and praying.

She didn’t go that night. Instead, she stabilized and for the next three days, remained essentially the same. There were restless periods when we had to move her from bed to easy chair or back again (she was light enough by then that any of us could carry her), there were many times when her breathing became so difficult we were sure it couldn’t go on, and some moments her mind was more clear and she was able to communicate, but there were never any moments when we thought things were turning around. We knew that any breath could be her last.

For the rest of the week, there was always at least one or two of us at Mom’s side (along with family and friends that visited), keeping vigil, making sure she didn’t try to get out of bed on her own diminished strength, putting ice chips on her tongue when her throat was scratchy, or just holding her hand. During one of those times, when Mom was sleeping fairly peacefully in the bed, I picked up my new book and started reading.

Terry Tempest Williams’ mother told her, “I am leaving you all my journals. But you must promise me that you will not look at them until after I am gone.” After her mom died, Williams found three shelves of beautiful clothbound journals. Every one of the journals was completely empty.

When Women Were Birds is Williams’ meditation on what those journals mean and what it means for a woman to have a voice. All of this is set against a backdrop of bird-watching and bird-listening. Birds, after all, never question whether or not they should sing and they never try to sing in a voice that’s not their own.

Raised in a Mormon home, where women’s voices were often silenced, Williams struggled with finding her own voice and trusting it to speak of those things she cared about. She cares deeply about the natural world and we now know her to have a clear and resonant voice on issues related to environmental abuse, but before she could become the advocate she is today, she had to go through much learning, grief, and growth.

To say that it was profound to read When Women Were Birds at my mom’s deathbed, while I witnessed Mom’s voice and spirit decline and disappear, would be an understatement. There were so many layers of significance going on for me at that time that I can hardly begin to explain what it meant.

My mom lived most of her life without trusting her own voice. Always insecure, she believed she had little of value to say. She was always quite certain that there were smarter people than her who should be listened to, and so she believed her voice meant little. It didn’t help that she was raised in a religious tradition that didn’t encourage women to speak, or that she married two men who were both more confident or sure of their own opinions than she was. What she failed to recognize was the fact that her “voice” came through loud and clear in the great love she offered people. She didn’t need to speak to be a healer of wounded souls.

To be honest, there’s always been some disconnect with my Mom when it comes to trusting my own voice. Though I never doubted that she loved me and was proud of me, she didn’t really understand what I felt I needed to speak of in the world. When I was writing plays, she came to watch, but usually said “it was good, but I didn’t really understand what was going on.” The same can be said for my published articles and blog posts. She always claimed that she was “too stupid to understand”.

In recent years, while I’ve been growing my body of work, I’ve had a hard time sharing what I do with my Mom. Some things – like the teaching I do at the university – was fairly easy for her to grasp, but other things just didn’t make sense to her. For one thing, she remained committed to a Christian tradition that frowned upon women in leadership, so when I started teaching women how to lead with more courage, creativity and wild-heartedness, it didn’t really fit with her paradigms. Nor did it make sense to her that I would seek a feminine divine or a feminine way of looking at spirituality.

Reading the book at Mom’s bedside left me somewhat conflicted.

On the one hand, I mourned the fact that Mom had been trapped by a lack of self-esteem and a religion that kept her voice silent. On the other hand, I honoured the fact that Mom always lived her life rooted in a deep love for other people.

On the one hand, I was disappointed that I’d never been able to fully share the importance of my work with my Mom. On the other hand, I’ve been taught by her to use my God-given gifts to make the world a better place.

On the one hand, my Mom was never able to fully validate or appreciate my writing or teaching. On the other hand, she’d raised me with so much love that I have the confidence I need to keep doing it without external validation.

On the one hand, I wished I could tell her about the work I’m doing for Lead with your Wild Heart and how I believe it will be life-changing for me and the women who participate. On the other hand, I knew that just sitting there and being present in the grief, without trying too hard to make it something it isn’t, was going to leave me with profound lessons that will enrich my teaching for years to come. And I knew that some of my wild-heartedness had been learned by watching her.

There have been times, in the last year and a half since Mom received her cancer diagnosis, that I’ve felt sure that I’d need to resolve some issues with my Mom. I thought I’d need to have a few more heart-to-heart talks with her before she died, finally helping her to understand where my views are different from hers and why I feel called to do this work that I do. But then, in recent months, that began to soften. I no longer felt the need for resolution. Instead, I simply felt the need to be there, to sit with her and enjoy her presence and bask in her love in those final months.

In the last week of her life, we didn’t do much talking. There was much that had been left unsaid. But that was okay. I didn’t need her to understand me. I didn’t need her to validate my choices. I simply needed to trust that she loves me and that she always has.

In the last week of her life, we didn’t do much talking. There was much that had been left unsaid. But that was okay. I didn’t need her to understand me. I didn’t need her to validate my choices. I simply needed to trust that she loves me and that she always has.

Once, when Mom was sitting in her big easy chair, she turned to me as if to communicate something. I leaned in to hear her whisper, but she didn’t speak. Instead she put her hand on my head and held it there while she looked deeply into my eyes, like a priest offering a blessing. My eyes filled with tears.

Another time she became restless and I thought she wanted to be moved, so I bent my head and prepared to pick her up. Instead, she wrapped her arms around me and kissed the top of my head several times, and then she smiled. I smiled back.

By Thursday, I was pretty sure she was slipping away. Her eyes had become more distant and she spent less and less time in the plane of reality that the rest of us remained in. By then, we were ready to let her go. I went home that night for the first time, hoping to get a few more hours of sleep. Around three, when my brother Dwight and sister Cynthia were sitting with her, she became suddenly more clear and happy than she’d been in a long time. “I made it!” she said. “I’m here!” When Dwight asked if she was in heaven, she said “yes!” And then it seemed like she was being introduced to people who’d passed before her.

At 4:00, they called me and woke my brother Brad. I rushed to her house, hopeful that a deer wouldn’t jump out at me on the dark highway. Instead, a ghostly bird fluttered through my headlights. By the time I got there, she’d already died. She stopped breathing for a few minutes, but when Cynthia said “oh Mom – you were supposed to wait until Heather got here!” she started up again. When I arrived, she was breathing but in a coma. There was no more life in her eyes. I sat with her for a few hours, and then as morning came, her breath became more and more fluid-filled. At 8:26, she finally stopped.

Shortly after that, a woodpecker came to Mom’s feeder and Cynthia snapped the photo at the top of this page. A few days later, the day we buried Mom next to Dad in the small town where we grew up, Cynthia spotted another bald eagle.

This week, I am back at work, writing more lessons for Lead with your Wild Heart. No, it’s not something my Mom understood, but that’s okay. I know that I have her blessing to use my gifts and share my voice, and this is what I am called to do.

Like a bird, I will go on singing, and the grief in my voice will only make it richer.

“Once upon a time, when women were birds, there was the simple understanding that to sing at dawn and to sing at dusk was to heal the world through joy. The birds still remember what we have forgotten, that the world is meant to be celebrated.” – Terry Tempest Williams

by Heather Plett | Nov 13, 2012 | Uncategorized

The more conversations I have in preparation for Lead with your Wild Heart, the more I am convinced that this work is not optional. This work is critical. This work is what we are all being called to in one way or another. The world needs us to accept the invitation into this work.

Leading with your wild heart is not about abandoning everything we know and moving into the woods. It’s about engaging with the world around us. It’s about sitting in deep conversations with our neighbours. It’s about seeking more authentic ways to live. It’s about having the courage to tell the truth.

Why is it important that people get in touch with and learn to lead with their wild/authentic/creative/expressive/vulnerable hearts?

I’ll let some of the members of my wisdom circle share their thoughts on this question:

Julie Daley: “Leadership is nothing without love, connection, and relationship. And where do we find love, connection, and relationship? The heart: through a wild and authentic heart that pulses and beats with the width and breadth of our humanity. It is in our full humanity that we find our way to true leadership, a leadership that invites others into their own wholeness and personal leadership.”

Filiz Telek: “Because the world calls for it right now! and our survival literally depends on it. The heart is the doorway to a wholesome, healthy, joyful, authentic life beyond right and wrong.”

Ronna Detrick: “My impulsive response to this is that you can’t lead if you’re not doing in with a wild/authentic/creative/expressive/vulnerable heart. My calmer response is to say that, of course, leading can take place, but I’d wonder if it’s really you that’s doing so if it’s in any form that’s not all that wildness and heartness. We are so enculturated to understand and recognize leadership in a particular way…andrarely with words like “wild” and “heart.” To get in touch with and lead from this place has the potential to change EVERYTHING!”

Lisa Wilson: “We’ve been asleep for far too long. We have reached a point in our collective evolution, a turning point, where the calls of something more can no longer be ignored. The wild heart of each individual, beating to a knowing that goes far beyond logical understanding, holds the paths to our healing. There is no one else who can heal you but you, and there is no other time to heal than now. The wild, creative heart longs to be heard, acknowledged, and to be the rhythm to which you take every step. There are many who still do not hear the calls; thus, those who can hear have a responsibility to guide themselves and others towards this awakening. It is time.”

Hali Karla: “Because the world needs it more than ever. The world is changing and our heart-wisdom is all too often left forgotten in our daily lives and how we interact with one another. In a world based on segmentation, we’ve nearly forgotten the primal power of true connection and devotion to our vulnerable selves and source. That is why people ache deep down for compassion, expression, soul-integration and belonging – and that is also exactly why change is coming. Because it is needed and desired, deeply. It is time to remember our inherent potential. Nature has this way of balancing itself out in the end. Regardless of how humans occupy themselves they are part of this amazing balance. Big changes and innovations, new paradigms of leadership and connection, and living in harmony with ourselves and our world will require adaptability, flexibility, deep self-awareness and radical empathy… this begins within, in the rivers where our own passions flow, uninhibited. And the more of us who choose to lead with the light from this intention, the more others will be inspired to step into that light and begin to explore the exponential beauty and transformation of heart-centered, sustainable, community-focused creative potential.”

Jodi Crane: “Because that’s where the joy is. That is using your creative gifts for good, being self-actualized, and living your full potential. Why would you not want to do that?”

Michele Lisenbury Christensen: “Our tendency – as pushed by both our brain structure and our culture – is to lead with our tough, logical, organized, methodical, clenchy, stiff-upper-lip selves. And all those qualities ARE valuable. Challenge is, we’ve got ’em in spades, and they crowd out the softer, wilder, more emotionally connected, more intuitive, more humane aspects of our power and our leadership. And when that happens, our capacity to respond effectively is dampened. We can’t, without our wild hearts, be present to our own emotions, our messy processes. We can’t be agile with the human process of coming with change. We can’t make difficult decisions that necessarily have downsides, and be present through the inevitable turbulence in their wake. We can’t be truly courageous without our vulnerability; we can only be brave. And that’s a pale substitute.”

Ann-Marie Boudreau: “That is where intuitive creation resides, where our own unique gifts are born and make their way into the world where they become a part of the process of evolution in moving all sentient and non-sentient beings forward on the path of life. It is in this place where we all dance together in community creating and shaping the world around us, unfolding our earth story before us with the dawn of each new day.”

By the way, my dear reader, YOU ARE IN MY WISDOM CIRCLE TOO! Join the conversation. Add your response to the question in the comments below. Why is this important?

Note: Registration for Lead with your Wild Heart is still open. You can download the first lesson free here. Join us in this exciting conversation about what can happen for the world if we step into our wild hearts.