by Heather Plett | Dec 4, 2012 | beauty

The woodpecker that visited Mom's feeder shortly after she died, photo by my sister Cynthia

In the last few months of her life, Mom spent a lot of time watching birds. I often sat and watched with her, marvelling at the variety that came to visit. We don’t have much of a history of bird-watching in our family, but we do have a history of paying attention to nature. One of the things that came up at Mom’s funeral was that whenever she went on road trips, she always hoped she’d be the first to spot wild animals. I’ve always been the same.

On one of our last visits, my sister and I spotted a large bald eagle perched in a tree not far from Mom’s house. It’s unusual to see bald eagles where we live, so it seemed an omen of sorts – perhaps bearing a message that our lives were about to change.

Two weeks ago, I brought a new bird book to Mom’s house, hoping we’d get to spend many hours leafing through the pages, trying to identify the birds that visit. Mom never looked at it. That was the day she began slipping away.

The next day, I was teaching at the university, but probably didn’t communicate much through my distraction. I kept my cell phone close, knowing I could get a call at any minute. At noon, after hearing from my brother that her health had declined quickly in the last 24 hours, my sister and I rushed out to be with her.

Before going, though, I made a quick trip to the bookstore. My friend Barbara had mentioned the book When Women Were Birds, by Terry Tempest Williams, and I knew that I had to have it. It’s a collection of short pieces on voice that Williams wrote after her own mother died. I tucked it into my purse.

Mom’s health declined so quickly that day that we were certain she would not live until morning. Her strength disappeared, her voice reduced to a whisper, her mind started slipping away, and she stopped eating and drinking. My siblings (two brothers and a sister) and my mom’s husband all sat with her, comforting her, singing hymns, reading her favourite Bible passages, and praying.

She didn’t go that night. Instead, she stabilized and for the next three days, remained essentially the same. There were restless periods when we had to move her from bed to easy chair or back again (she was light enough by then that any of us could carry her), there were many times when her breathing became so difficult we were sure it couldn’t go on, and some moments her mind was more clear and she was able to communicate, but there were never any moments when we thought things were turning around. We knew that any breath could be her last.

For the rest of the week, there was always at least one or two of us at Mom’s side (along with family and friends that visited), keeping vigil, making sure she didn’t try to get out of bed on her own diminished strength, putting ice chips on her tongue when her throat was scratchy, or just holding her hand. During one of those times, when Mom was sleeping fairly peacefully in the bed, I picked up my new book and started reading.

Terry Tempest Williams’ mother told her, “I am leaving you all my journals. But you must promise me that you will not look at them until after I am gone.” After her mom died, Williams found three shelves of beautiful clothbound journals. Every one of the journals was completely empty.

When Women Were Birds is Williams’ meditation on what those journals mean and what it means for a woman to have a voice. All of this is set against a backdrop of bird-watching and bird-listening. Birds, after all, never question whether or not they should sing and they never try to sing in a voice that’s not their own.

Raised in a Mormon home, where women’s voices were often silenced, Williams struggled with finding her own voice and trusting it to speak of those things she cared about. She cares deeply about the natural world and we now know her to have a clear and resonant voice on issues related to environmental abuse, but before she could become the advocate she is today, she had to go through much learning, grief, and growth.

To say that it was profound to read When Women Were Birds at my mom’s deathbed, while I witnessed Mom’s voice and spirit decline and disappear, would be an understatement. There were so many layers of significance going on for me at that time that I can hardly begin to explain what it meant.

My mom lived most of her life without trusting her own voice. Always insecure, she believed she had little of value to say. She was always quite certain that there were smarter people than her who should be listened to, and so she believed her voice meant little. It didn’t help that she was raised in a religious tradition that didn’t encourage women to speak, or that she married two men who were both more confident or sure of their own opinions than she was. What she failed to recognize was the fact that her “voice” came through loud and clear in the great love she offered people. She didn’t need to speak to be a healer of wounded souls.

To be honest, there’s always been some disconnect with my Mom when it comes to trusting my own voice. Though I never doubted that she loved me and was proud of me, she didn’t really understand what I felt I needed to speak of in the world. When I was writing plays, she came to watch, but usually said “it was good, but I didn’t really understand what was going on.” The same can be said for my published articles and blog posts. She always claimed that she was “too stupid to understand”.

In recent years, while I’ve been growing my body of work, I’ve had a hard time sharing what I do with my Mom. Some things – like the teaching I do at the university – was fairly easy for her to grasp, but other things just didn’t make sense to her. For one thing, she remained committed to a Christian tradition that frowned upon women in leadership, so when I started teaching women how to lead with more courage, creativity and wild-heartedness, it didn’t really fit with her paradigms. Nor did it make sense to her that I would seek a feminine divine or a feminine way of looking at spirituality.

Reading the book at Mom’s bedside left me somewhat conflicted.

On the one hand, I mourned the fact that Mom had been trapped by a lack of self-esteem and a religion that kept her voice silent. On the other hand, I honoured the fact that Mom always lived her life rooted in a deep love for other people.

On the one hand, I was disappointed that I’d never been able to fully share the importance of my work with my Mom. On the other hand, I’ve been taught by her to use my God-given gifts to make the world a better place.

On the one hand, my Mom was never able to fully validate or appreciate my writing or teaching. On the other hand, she’d raised me with so much love that I have the confidence I need to keep doing it without external validation.

On the one hand, I wished I could tell her about the work I’m doing for Lead with your Wild Heart and how I believe it will be life-changing for me and the women who participate. On the other hand, I knew that just sitting there and being present in the grief, without trying too hard to make it something it isn’t, was going to leave me with profound lessons that will enrich my teaching for years to come. And I knew that some of my wild-heartedness had been learned by watching her.

There have been times, in the last year and a half since Mom received her cancer diagnosis, that I’ve felt sure that I’d need to resolve some issues with my Mom. I thought I’d need to have a few more heart-to-heart talks with her before she died, finally helping her to understand where my views are different from hers and why I feel called to do this work that I do. But then, in recent months, that began to soften. I no longer felt the need for resolution. Instead, I simply felt the need to be there, to sit with her and enjoy her presence and bask in her love in those final months.

In the last week of her life, we didn’t do much talking. There was much that had been left unsaid. But that was okay. I didn’t need her to understand me. I didn’t need her to validate my choices. I simply needed to trust that she loves me and that she always has.

In the last week of her life, we didn’t do much talking. There was much that had been left unsaid. But that was okay. I didn’t need her to understand me. I didn’t need her to validate my choices. I simply needed to trust that she loves me and that she always has.

Once, when Mom was sitting in her big easy chair, she turned to me as if to communicate something. I leaned in to hear her whisper, but she didn’t speak. Instead she put her hand on my head and held it there while she looked deeply into my eyes, like a priest offering a blessing. My eyes filled with tears.

Another time she became restless and I thought she wanted to be moved, so I bent my head and prepared to pick her up. Instead, she wrapped her arms around me and kissed the top of my head several times, and then she smiled. I smiled back.

By Thursday, I was pretty sure she was slipping away. Her eyes had become more distant and she spent less and less time in the plane of reality that the rest of us remained in. By then, we were ready to let her go. I went home that night for the first time, hoping to get a few more hours of sleep. Around three, when my brother Dwight and sister Cynthia were sitting with her, she became suddenly more clear and happy than she’d been in a long time. “I made it!” she said. “I’m here!” When Dwight asked if she was in heaven, she said “yes!” And then it seemed like she was being introduced to people who’d passed before her.

At 4:00, they called me and woke my brother Brad. I rushed to her house, hopeful that a deer wouldn’t jump out at me on the dark highway. Instead, a ghostly bird fluttered through my headlights. By the time I got there, she’d already died. She stopped breathing for a few minutes, but when Cynthia said “oh Mom – you were supposed to wait until Heather got here!” she started up again. When I arrived, she was breathing but in a coma. There was no more life in her eyes. I sat with her for a few hours, and then as morning came, her breath became more and more fluid-filled. At 8:26, she finally stopped.

Shortly after that, a woodpecker came to Mom’s feeder and Cynthia snapped the photo at the top of this page. A few days later, the day we buried Mom next to Dad in the small town where we grew up, Cynthia spotted another bald eagle.

This week, I am back at work, writing more lessons for Lead with your Wild Heart. No, it’s not something my Mom understood, but that’s okay. I know that I have her blessing to use my gifts and share my voice, and this is what I am called to do.

Like a bird, I will go on singing, and the grief in my voice will only make it richer.

“Once upon a time, when women were birds, there was the simple understanding that to sing at dawn and to sing at dusk was to heal the world through joy. The birds still remember what we have forgotten, that the world is meant to be celebrated.” – Terry Tempest Williams

by Heather Plett | Nov 30, 2012 | Uncategorized

Mom & I, in the summer when she thought she'd beaten cancer

I sit down to write a blog post, and all that comes out is… I don’t have a mother anymore.

I try to write in my journal, and the only words that show up on the page are… I’m an orphan now. I don’t know how to be an orphan.

I turn to my work, and all I can do is stare at the blank page and think… Who am I now that both of my parents are dead?

I wander around the house aimlessly. I can barely focus enough to wash the dishes. I watch mindless TV. I putter. I sit long minutes lost in thought.

I phone my mom’s husband, my mom’s cheery voice comes on the answering machine, and I fall to pieces. It’s hard to leave a message when the one I really want to talk to won’t return my call.

Last week, when Mom was slipping away, and her mind was no longer always clear, she looked at me with sadness in her eyes. “I don’t know how to do this,” she said, in her nearly invisible voice. “I know Mom,” I said. “I don’t know how to do this either.”

And that’s how I still feel. “I don’t know how to do this.”

I don’t know how to get used to the fact that I can’t pick up the phone and call Mom. I don’t know how to write this grief in any way that makes sense. I don’t know how to tell you the story of what it meant to watch her die. I don’t know how to make meaning of the days of vigil, watching her slip away, carrying her emaciated body from bed to chair when she became restless, waking in the night to care for her, listening to her gurgling hanging-on-to-life breath.

I don’t know how to speak with this lump in my throat.

I don’t know how to be at the top of the family tree, the oldest woman in my line of descendants. I’m much too young to be the matriarch. I don’t want to take on that responsibility.

Last Saturday, when I was supposed to be hosting a day retreat for women of courage, I spent the day planning my Mom’s funeral. Instead of being the teacher, I was the student again, forced to learn new lessons in courage.

Grief is a cruel teacher. I want to skip this class. I want to rebel, climb out the window, and run away to a place where my Mom and Dad and son are still alive. I don’t want to stay here and write the test. Not again, please. I’ve been through this class a few times already – can’t I get an exemption this time? Can’t I just be the teacher now without having to learn any more of these difficult lessons?

I haven’t been given a choice though. I have to stay here and learn the lessons I have yet to learn. I have to pay attention – to be present in the pain, to let the tears come, to let the panic wake me in the night, to remember again and again what her empty eyes looked like when the breath left her body. I have to let another death change my life.

I have to bear the burden of this fresh crack in my heart, remembering that the pain is telling the story of the privilege of being loved. I have to remind myself that my heart can break without falling apart because it has been made resilient by love. My life can feel this emptiness because I’ve known fullness.

I will get angry at the teacher now and then, and I will lay my head down on my desk when the learning feels too heavy, but I will stay here in this class. There’s nothing “fair” about it, and right now the pain is blinding me from seeing the blessings, but, in the end, I know I will be richer and wiser for having had the courage to love and the courage to grieve.

My heart is broken, but I will learn to dance with a limp.

“You will lose someone you can’t live without,and your heart will be badly broken, and the bad news is that you never completely get over the loss of your beloved. But this is also the good news. They live forever in your broken heart that doesn’t seal back up. And you come through. It’s like having a broken leg that never heals perfectly—that still hurts when the weather gets cold, but you learn to dance with the limp.” ― Anne Lamott

by Heather Plett | Oct 12, 2012 | change, Labyrinth

It was remarkable how many people responded to my last post, through emails, comments, and Facebook posts. Repeatedly people said some version of: “YES! This is what I need too! I’ve been feeling so lost and your post felt like permission to tear up the maps and simply surrender to the path that lays itself out before me.”

It seems a lot of people need lack-of-vision boards instead of vision boards. It seems we all need to re-learn the importance of surrender.

In our goal-obsessed, vision-board-creating, be-busy-or-be-nothing, success-driven culture, we have forgotten something that’s really, really important.

There is great value in getting lost.

It’s true. We can’t go through the journey of life without letting ourselves get profoundly lost sometimes. The places where we get lost – where we surrender to the spiritual spirals that takes us into a deeper knowing, where we give up on the expected outcome and let something new emerge – those are the places in which we are transformed.

Yesterday, I curled up in bed next to my Mom and I wept over the way cancer is stealing her body and her energy. I wept for the things we can no longer do together. I wept for the future ahead that looks foreign and unfriendly. I wept for the great loss that the end of her life will bring. I wept because I felt utterly and completely lost.

Nobody gives you a roadmap for losing a parent. Nobody teaches you a course in how to watch cancer destroy someone you love. Nobody prepares you for a detour into the spiralling vortex of grief.

This one thought gave me some comfort me in my grief… I am SUPPOSED to feel lost. I’m supposed to feel like a ship that’s lost its anchor, tossed about on these unpredictable waves of longing and loss. I’m supposed to feel like the ground has been pulled out from underneath me and I am desperately clutching for something to keep me from falling.

This is all part of the process. This is all part of my journey.

Don’t get me wrong – just because I am deeply familiar with the chaos of grief, doesn’t make this easy. It’s excruciating and I’m fighting my way through waves of anger, heartache, and bitterness. “Must I go through this AGAIN?!” I shout to the heavens. “Isn’t it enough that Dad died in a ditch and it felt like that tractor had driven over my heart and not just his? Do you have to take Mom away too?”

I rant and I rave and I cry, but at least I give myself permission to be lost. At least I don’t have any unrealistic expectations of “closure” or “acceptance” or “5 steps through grief”.

Back in June, I took part in a change lab in which we walked through Theory U, a rich and meaningful process that helps groups (and individuals) move through change by letting go of the past, “presencing” what is to come, and then, with an open heart and open mind, letting the new thing come. It wasn’t ostensibly designed to teach us about grief, but grief is part of every change process and so the two are closely intertwined. To get through any transformational change, we need to let go and let come. Like walking the labyrinth, we need to release, receive, and return.

In this profound place of loss in which I find myself again, I’m taking another deep dive into the U curve, letting go of the past, accepting the chaos, being present in the loss. All the while, I am connecting to Source, opening my heart and opening my mind to the new future.

This will change me. I will shed a lot of tears and release a lot of anger. It will tear me apart and then rebuild me into something new. It will be a stronger version of myself. I know this to be true. I am stronger for the paths of grief I have walked down. I am wiser for the loss I have suffered. I am more compassionate because I have graves to visit. I can call myself a “guide on the path through chaos to creativity” because I am deeply familiar with chaos and loss.

Remember this… You have permission to be lost. You have permission to let go. You have permission to dive into the bottom of the U, not knowing what will emerge after the surrender. You have permission to cry and rant and rave. You have permission to tear up maps and destroy the pretence of paths. You have permission to not make any goals but instead to surrender to what comes.

Let go, and then let come. And in between, keep breathing.

by Heather Plett | Oct 10, 2012 | Uncategorized

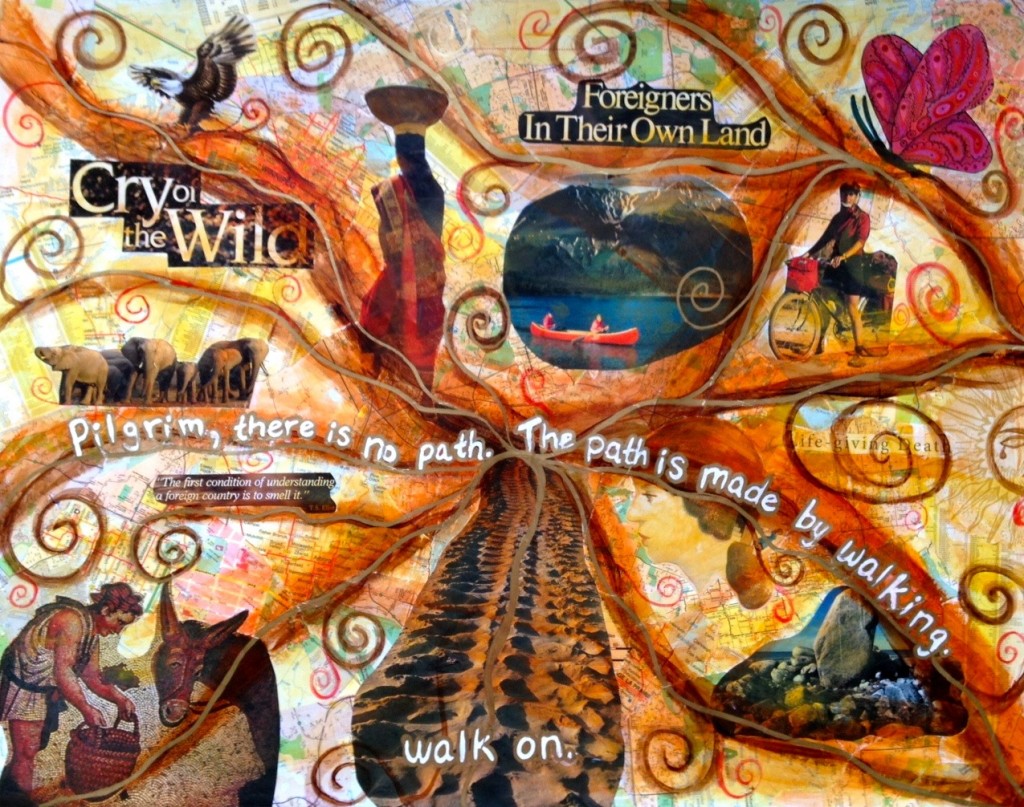

Every few months, I like to make a vision board. It’s my feminine, right-brained version of strategic planning. Instead of filling a page with boxes and goals and strategies, I fill it with images and words plucked from magazines that I feel drawn to and that my intuition tells me have something to do with the direction my heart is heading.

I haven’t made a vision board in a long time. One day in August, I sat with my mom in an oncologist’s office and heard the words “cancer spreading” and “six to twelve months to live”, and since then, my vision is too narrow for a vision board. The only thing I can see in my future is “fatherless, motherless daughter” and that’s hard to pluck from a magazine.

Since then, my focus and energy have been limited, at best. Not only am I dealing with grief, but I’m dealing with a pretty serious lack of paying work because I just don’t have what it takes to drum it up right now. I’m looking for part time work that will bring in some income while I deal with whatever the future holds.

Where’s the “vision” in all that? Pay the bills, feed the kids, sit with Mom, worry about money, drive the kids to where they need to go, visit Mom again… that’s about all I can muster these days.

This week, though, my friend Segun dropped off a bag of old maps, and suddenly I found myself missing my paints and scissors and Mod podge. Something about those old maps made me want to create again.

Tearing up old maps can feel surprisingly cathartic when there’s no roadmap for the journey you’re traveling along. I tore and I placed and I glued. I shredded roads and lined them up with wasteland. I tore up countries and provinces. I cut lakes in half. I destroyed international borders. I had no idea what was emerging, but it felt good to destroy and then to begin to create again.

After the page was full of torn map pieces, I turned to my stack of old magazines. Not a lot in them inspired me. I wasn’t dreaming of parties or feasts or published books or beautiful retreats. All of that felt foreign and far away.

Suddenly I realized that instead of making a “vision board”, I was making a “lack of vision board”. Something about that acknowledgement felt like a release. I didn’t have to find anything in the images. I didn’t need it to be anything. Maybe just tearing up map pieces was enough for now. Maybe it was the journey and not the destination that I needed.

I left it alone for awhile. I made a pot of soup and sat down to stare out the window while I ate.

Eventually, I came back to it, knowing I wanted to add something more. Paint? Images? I had no idea. I was listless and unfocused, the way I spend much of my time these days.

A few images and words caught my attention. Images related to being on a journey – a man feeding his donkey, a couple in a canoe, a woman on a bicycle, the path of a turtle returning to the sea, a woman carrying her basket on her head. And then there were several images related to the wild – elephants, a butterfly, an eagle, balanced rocks in the tundra. The words were similar – bleak, restless, and a little wild. “Foreigner in their own land.” “The first condition of understanding a foreign country is to smell it.” “Cry of the wild.” “Life-giving death.”

I glued the pieces on. They were sparse on my huge paper, but I didn’t feel like adding more. I didn’t feel like overlapping images the way I usually do. I didn’t want them to touch.

I grabbed my paint. There was too much clarity on the board – I needed it to be muddier. I started adding layers of ochre, orange, and brown – first a wash, then random brushstrokes.

Suddenly I realized that the brushstrokes weren’t random at all. I was creating a series of intertwining paths connecting the images and words. It was all about a journey, but this was no clear map-driven journey. It was random and chaotic, with detours and bumps and unexpected curves. A map to nowhere and everywhere, all at once.

To the paths, I added even more detours – spirals jutting out at random intervals – the pauses along the journey where one must take a deeper spiritual journey before returning to the path.

When the paths were finished, I added the words that came to me: “Pilgrim, there is no path. The path is made by walking.” (from a poem by Antonio Machado) And at the bottom, I added a note just for me. “Walk on.”

I am very fond of my lack-of-vision board. It speaks to me of surrender, trust, and pilgrimage. It tells me to stop trying to control things, to accept the detours when they show up, and to be willing to pause for nourishment and spiritual spiralling. It tells me to follow my wild heart and just keep walking. It lets me know that the detours are not mistakes. It doesn’t expect me to be perfect or focused or even strong. It just lets me be who and where I am right now.

I especially like that at the top left, where the paths seem to be heading, there’s a fierce beautiful eagle taking flight and heading into the light.

* * * * * *

A Lack of Vision Board is one of the exercises you’ll find in Pathfinder: A Creative Journal for Finding your Way.

by Heather Plett | Oct 4, 2012 | Beauty, beginnings, Community, Creativity, fearless, hope, journey, Leadership

I have seen too many wounded women.

I have seen too many wounded women.

I have watched them lose the light in their eyes when the shadows overcame them.

I have heard a thousand reasons why they no longer give themselves permission to live truthfully.

I have seen too many wild hearts tamed.

I have witnessed the loss of courage when it’s just too hard to keep being an edgewalker in a world that values conformists.

I’ve recognized the fear as they take tiny brave steps, hoping and praying the direction is right.

“I feel guilty whenever I indulge in my passions. It feels selfish and irresponsible.”

“My husband doesn’t like it when I talk about feminine wisdom, so I keep it to myself.”

“If I write the things that are burning in my heart, it will freak people out. So I remain silent.”

“I used to love wandering in the woods, but I never have time for it anymore.”

“I just want to have a real conversation for a change. I want to feel safe to speak my heart.”

“My job makes me feel dead inside, but I don’t know what else I can do.”

“People expect me to be strong and hide my feelings now that I’m in leadership. I feel like I have too much bottled up inside that I can’t share with anyone.”

“Sometimes I think there must be something wrong with me. I just don’t fit in.”

“There is so much longing in the world. I get lost in that longing and don’t know how to sit with it.”

“I wanted to be a painter, but I needed a real career. I haven’t painted in years.”

“People think I’m strange when I share my ideas, so I’ve learned to keep them to myself.”

“I can’t go to church anymore. I don’t feel understood there. But I haven’t found another place where I can find community, so I often feel lonely.”

“There’s a restless energy inside me that wants to be free. I long to be free.”

So much woundedness has been laid tenderly on the ground at my feet.

So many women want their stories validated. Their fears held gently. Their tiny bits of courage honoured.

I hear them whisper “please hear me” through clenched teeth.

I see the tears threaten to overflow out of stoic eyes.

I recognize the longing.

I know the brokenness.

I feel the ache of silenced dreams.

They come to me because they know I have been broken too.

They trust me with their whispers because I am acquainted with fear.

They look to me for courage and understanding because they witness my own long and painful journey back to my wild heart.

I see you.

I know you.

I honour you.

I love you.

You are beautiful.

You are courageous.

You are okay.

You can be wild again.

You can trust your heart. She will not lie to you.

You can live more fully in your body. She will welcome you back.

You can go home to that part of you that feels like it’s been lost.

You can find a circle of people who will understand you.

You can step back into courage.

You have permission to be an edgewalker.

You have permission to speak the things that you’re longing to say.

You have permission to be truly yourself.

You have permission to step away from your responsibilities for awhile.

You have permission to wander in the woods.

You also have permission to be afraid.

And to wait for the right time.

And to sit quietly while you build up your courage.

You don’t need to do this all alone.

And you don’t need to do it all at once.

You don’t need to shout before you’re ready to whisper.

You don’t need to dance before you’ve tried simply swaying to the music.

You can give your woundedness time to heal.

Take a small step back into your self.

Move a little closer to your wild heart.

Pause and touch the wounded places in you.

Just breathe… slowly and deeply.

And when you’re ready, we can do this together.

If this post resonates, please consider the following:

1. Join me as I host a circle of amazing women at A Day Retreat for Women of Courage in Winnipeg on October 20th. Pay what you can.

2. I’m creating a new online program called Lead with Your Wild Heart (related to the themes in this post) that feels like a coming together of a thousand ideas that have filled my head in recent years. Add your name to my email list (top right) to be the first to hear about it and to receive a discount.

In the last week of her life, we didn’t do much talking. There was much that had been left unsaid. But that was okay. I didn’t need her to understand me. I didn’t need her to validate my choices. I simply needed to trust that she loves me and that she always has.

In the last week of her life, we didn’t do much talking. There was much that had been left unsaid. But that was okay. I didn’t need her to understand me. I didn’t need her to validate my choices. I simply needed to trust that she loves me and that she always has.