by Heather Plett | Mar 14, 2016 | Uncategorized

A few weeks ago, I had the pleasure of speaking at a storytelling event hosted by Manitoba Council for International Cooperation. I shared a story about the journey that lead me from the work I once did in international development to the work I now do.

Here’s the audio recording of that talk… (even though it looks like a video, don’t be fooled – it’s audio)

And here are the notes from the talk I gave…

Building relationships that bridge differences

It all started with a blog post.

In December of 2004, in the same year that Wikipedia says blogs became mainstream, I wrote my first blog post. I think my sister-in-law was the only person who read it.

The blog post represented a personal quest I’ve been on for a good part of my life – a quest to build meaningful relationships that bridge differences.

At the time I was preparing for my first trip to Africa. I was the newly-minted Director of Communication and Education at Canadian Foodgrains Bank and I was going on a food study tour to learn more about what the organization did.

I had long dreamed of going to Africa, ever since the first time I could remember a missionary carrying their slide projector into the tiny rural church I grew up in. When I saw those vivid, sun-drenched images, I dreamed of going to Africa, but I didn’t dream of being a missionary. Instead, I wanted to be a gypsy. I wanted to dance around open campfires, live in a caravan, and change my scenery every day. I wanted to live on the edge of civilization. And I wanted to do it with the beautiful people I saw on those slides.

Despite my long-held dream, a trip to Africa presented a challenge for me. The challenge was that I didn’t know how to bridge the differences that I knew would be there. I didn’t know how to step peacefully onto African soil, with my white skin undeniably connecting me to colonialism and my role as “donor” undeniably creating a power imbalance between myself and the people I’d meet. I didn’t know how I’d create the kind of space for one of the things that most ignites me – meaningful, openhearted, reciprocal conversation.

I didn’t know how, but I wanted to try. Here’s the commitment I wrote on that blog post…

I won’t preach from my white-washed Bible. I won’t expect that my English words are somehow endued with greater wisdom than theirs. I will listen and let them teach me. I will open my heart to the hope and the hurt. I will tread lightly on their soil and let the colours wash over me. I will allow the journey to stretch me and I will come back larger than before.

I did indeed come back stretched, and I’d fallen in love with Africa, as I knew I would, but I also came back troubled. Despite my best efforts, there were many times on that trip when my white skin, my English words, and my purpose for being there served as a barrier. I hadn’t figured out what to do to meet them in an equitable way. I was no gypsy, dancing around the fire with them.

In one of the most memorable moments of that trip, we traveled to a remote village in Tanzania to be part of a food distribution in a region where people had suffered from a few years of drought. I traveled with the local bishop, a jolly man whose position afforded him a fancy car, a patient driver, and the adoration of many parishioners.

Along the way, we stopped at a grocery store and the driver ran inside for bread and juice boxes. “It’s for my diabetes,” the bishop said, passing some to the backseat. I felt like I was receiving communion.

When we arrived at the food distribution site, the car was instantly surrounded by hundreds of people who wanted to get close to the bishop and his distinguished white guests from Canada. As I stepped out of the car, hands reached out to touch my clothes, my hair, and my skin. It was suffocating and I felt completely unworthy. This was what I’d least wanted on this trip – a painful reminder that I was undeniably “other” and undeniably privileged.

We were quickly ushered toward the place where hundreds – maybe thousands – of local people were waiting patiently for their food. They’d been waiting since sunrise in the heat of the sun and it was now mid-afternoon. The local authorities had insisted that nobody could take a bag of maize home until the Canadian donors had arrived.

The Bishop stepped forward to speak to the people. He spoke of how God was blessing them by sending them food in their time of hunger. He told them they needed to repent of their sins so that they could continue to receive God’s abundance. As I listened, I wondered what the villagers thought of us, traveling halfway across the world on the wings of our privilege. Did they assume we must be closer to God?

Then it was our turn – each of the Canadians in our delegation was pulled forward and invited to speak to the crowd through a translator. My throat felt tight. What would I say? How would I speak to them in a way that felt meaningful and not arrogant? How would I live up to my commitment to build a bridge?

Of course, in that moment, I was doomed to fail, but I did the best that I could. I reached into my own history of being raised poor on a farm that depended on the weather for good crops and told them I had some knowledge of their struggle and some empathy for what they were going through. It was a feeble attempt, and yes, it still smacked of privilege, but it was the only thing I could think of at the moment.

After we spoke, we were invited to scoop some of the maize into their bags for a “benevolent donors” photo op and then we were whisked away to not one but two feasts. “Eat halfly,” the bishop said with a chuckle at the first feast. “A second village also wants to honour you with a feast.” Though the local people had to wait for hours in the sun for a bag of maize, we were being whisked from one plentiful table to the next. It was hard to swallow.

A few years later, still wrestling with how to challenge the imbalance of power and privilege and meet people in the middle, I went to Bangladesh. I had a camera crew with me, and as we traveled, I kept looking for some little bit of magic that would allow us to enter the story not as privileged donors from a wealthy developed country, but as humans sitting with other humans in their time of need.

I decided that the theme of our video would be the many ways in which we are all connected. Through translators, we taught the local villagers to say “we are all connected” in English and then we learned to say it in their languages, hoping that would help us build a bridge. Of course, it was a bridge that took us only a few feet across the great divide, but it was a start. My favourite memory from that trip was the day a young girl in a red sari followed me around the village and kept popping up at my elbow and saying “we are all connected!” It was the only way she knew how to say hello to me and she simply wanted to be my friend.

My time at Canadian Foodgrains Bank was a rich time of learning, and I got better at telling the stories of development in ethical ways meant to connect rather than divide donors from recipients, but, after six years there, I realized I hadn’t ever fully satisfied the quest I’d laid out in that first blog post. Some of that came with the limitations of my job – as a communicator and fundraiser, I was tasked with storytelling in only one direction, for one primary purpose, and that made reciprocity nearly impossible and reinforced my own access to power and privilege.

I quit my job in 2009 and instead of being a Director of Communication, I became a Facilitator of Conversations. My personal quest had let me to drop both the hierarchical title and the one-directional sharing of stories.

The first thing I did after leaving the Foodgrains Bank was to attend a workshop on The Circle Way – a methodology that invites people to sit in circle for meaningful conversation. This is something that had long intrigued me, and I sensed that it might give me some direction. I was right – it did. The circle changed everything. It changed the way I listened, it changed the way I spoke, it changed the way I sat across from people, and it changed the way I engaged power and privilege.

The circle is an inherently reciprocal shape with a leader in every chair. Every person in a circle holds equal responsibility for whatever happens in that circle and only with each person holding the rim is that circle strong. Often in the circle, we pass a talking piece so that only one person speaks at a time and everyone else listens. This focuses the conversation and teaches us to be fully present for each story. It also flattens the hierarchy and removes the structural symbols of power that felt so painful to me when I stood in front of rows and rows of people in that Tanzanian village.

Before long, the circle was part of every aspect of my life. I began to use it in university classrooms where I taught, I use it in retreats and workshops, and I even use it in one-on-one coaching sessions on Skype. Rarely do I stand in front of a crowd like I’m doing tonight. Instead, I sit with people, shoulder to shoulder and heart to heart. The practice is teaching me to be a more attentive, less controlling listener. It’s also teaching me how to challenge my own privilege, honour the differences in the room, and focus primarily on storycatching rather than storytellng.

I imagine each person I speak with is holding a talking piece and I can only speak when the piece is literally or figuratively passed to me. It doesn’t matter how much power or privilege you have – if you don’t hold the talking piece, you don’t speak.

In early 2015, another blog post changed my life. More than 1500 blog posts later, I was still wrestling with the same question I’d asked on the first post, but this time, I was ready to offer what I thought might be an answer. In my circle work, I’d come across the term “holding space” and the more I understood it, the more it connected with what I’d envisioned 11 years earlier.

Holding space is what we do for people when we listen without judging, walk alongside without trying to fix, empower without trying to control, and guide without inserting our own egos. In that blog post, I wrote about how a palliative care nurse had held space for my mom and my siblings and me when Mom was dying. Though she knew more than we did about how to support the dying, she never took our power away and she made us believe we had enough wisdom and strength to make the right decisions on our mom’s behalf.

Unlike my first blog post, this one was read by half a million people and, a year later, I still get almost daily emails from people about it. I am deeply humbled to know that there are many, many people on the same quest I’m on, trying to figure out how we can walk alongside people in meaningful, openhearted, and reciprocal ways without judging, fixing, or controlling their stories.

Around the same time as that blog post was catching fire, I had an opportunity to revisit the commitment I made on my original blog post, but this time it was closer to home. Winnipeg had just been named the most racist city in Canada and I felt a nudging to get involved in changing that. Together with Rosanna Deerchild, a talented Indigenous poet and broadcaster, I hosted a series of conversations about racism in our city. We invited people of all races and all levels of power and privilege to sit in circles, shoulder to shoulder and heart to heart, and we invited them to share their stories.

We may not have changed the city, but each of us who sat in those circles was changed by the conversations we had.

Unlike the stifling feeling at the front of the crowd in Tanzania, this time I felt my heart opening and I could breathe. I’ve still got a long way to go in understanding all of the complexities of how to build relationships that bridge differences, but at least I’m on the right path.

Won’t you join me on this ongoing quest?

by Heather Plett | Mar 11, 2016 | Beauty, calling

I have been sick this week, so I don’t have a lengthy reflection to share with you, but I thought I’d still take the time to offer one simple thought that came to me while I was in Vancouver.

I have been sick this week, so I don’t have a lengthy reflection to share with you, but I thought I’d still take the time to offer one simple thought that came to me while I was in Vancouver.

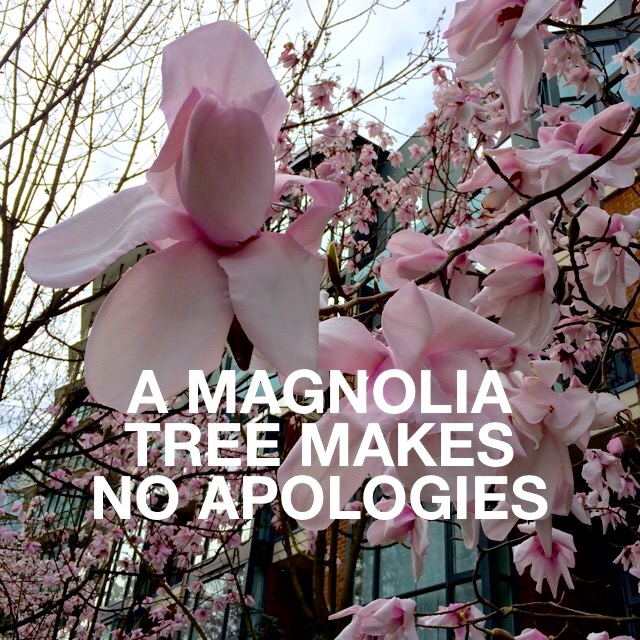

I was fortunate enough to be in Vancouver for the blooming of the magnolia trees. We don’t have magnolia trees in Winnipeg, so it’s a rare treat to see them in bloom.

The tree outside the window of my friend Lisa’s apartment wasn’t quite ready to burst open, so she drew me a map to make sure I’d get to see at least one tree in bloom before I went back home to the prairies. “Glorious magnolia tree” is what she wrote on the map, and I carried that map with me in search of beauty.

The tree outside the window of my friend Lisa’s apartment wasn’t quite ready to burst open, so she drew me a map to make sure I’d get to see at least one tree in bloom before I went back home to the prairies. “Glorious magnolia tree” is what she wrote on the map, and I carried that map with me in search of beauty.

The map did not disappoint. There wasn’t just one glorious magnolia tree but several lining a short block. Some of the blossoms were pale pink, some were white, and some were dark pink. All were in raucous, glorious bloom.

As I stood there, staring in awe at the sometimes refined and sometimes sloppy blossoms bursting out all over the trees, this thought came to me…

A magnolia tree makes no apologies.

It doesn’t ask permission to bloom. It doesn’t apologize for being big and bold and pink. It doesn’t worry if it’s not as demure as the tree down the street. It doesn’t hide its glorious blossoms behind leaves or branches.

There is not a moment’s hesitation in a magnolia tree’s fulfilment of its purpose. It only knows that it must live up to what’s put in its DNA to do. It only knows that it must respond appropriately to Spring’s invitation to burst into bloom or it won’t be able to produce seeds for future magnolia trees.

I wonder what it would be like if we all lived more like magnolia trees.

What if we simply trusted that each of us has a purpose that involves blooming and not hiding those blossoms? What if we dared to be big and bold and beautiful? What if we stopped worrying about how others will judge our shininess? What if our only authority on when to bloom were the seasons and not the people who prefer to keep us small?

If you want your life to amount to something – if you want to produce seeds that will grow beautiful things in the future – then you need to be prepared to burst into bloom when the time is right. No, you might not have a calling that looks as bold as a magnolia tree (perhaps you’re a tiny violet hidden in the grass close to the ground) but whatever you’re called to do…

Don’t apologize for bursting into bloom.

Just go ahead and burst open. And if it’s not your season to bloom, then rest for now and trust that the blooms will come.

by Heather Plett | Mar 1, 2016 | Uncategorized

I have the privilege of spending this weekend on Vancouver Island. While there, I’ll be teaching a writing workshop (join us in Comox?), sitting in circle with women, and connecting with several friends and colleagues.

In between, I’ll be wandering the shoreline, taking pictures of eagles, and exploring paths through woods and towns that are new to me. Hopefully I’ll catch at least one sunset or sunrise over the water.

Wherever I travel, I make it my intention to find the beauty in the local landscape, even if I only have a moment to do so.

I have a long-abiding love affair with beauty. It’s a love affair that runs deep through my bones, through my heart, and through my blood.

Yesterday, while I was doing a task that wasn’t particularly beautiful (cleaning mouldy, nearly unrecognizable food from the back of my fridge), I listened to a podcast that I listen to at least once a year – John O’Donohue talking about the importance of beauty. O’Donohue has been one of my greatest influences in my love affair with beauty. His book, Beauty: The Invisible Embrace, is one of the most well-fingered books on my shelves.

“When our eyes are graced with wonder, the world reveals its wonders to us. There are people who see only dullness in the world and that is because their eyes have already been dulled. So much depends on how we look at things. The quality of our looking determines what we come to see.” ― John O’Donohue, Beauty: The Invisible Embrace

Several years ago, when I still worked in international development, I traveled to two places where people lived in abject poverty – a village in the poorest region of Ethiopia and a village in the poorest region of India. The experiences in those two villages was strikingly different. I left one feeling happy and hopeful, having spent much of our time with the community laughing and dancing, and I left the other feeling sad and discouraged, having spent most of our time listening to their woes and heartache.

Since their economic status, access to land, etc., was essentially the same, I wondered what was different between the two communities. Here is my hypothesis… In the hopeful community, they still had eyes “graced with wonder” and in the other, their eyes “had already been dulled.” In the hopeful community, there was still a clear reverence for beauty. Their clothing, though old and somewhat tattered, was clean and well kept. The girls wore their hair with fanciful braids and beads, and the young men used butter to make their hair shiny and smooth. They danced for us and shared their music. In the other community, both women and men had given up combing their hair and nobody’s clothes looked well cared for. There was a look of deadness in their eyes. There was no sharing of their cultural dance or music.

I can’t tell you what came first, a loss of beauty or a loss of hope, and I don’t know about all of the contributing factors in either village nor do I have any right to judge them, but I can tell you that where there was beauty, there was a sense of hope. And where there was a lack of beauty, there was little hope. The two were clearly link, one way or another.

I believe this to be true in all of our lives – beauty and hope are intertwined. So are beauty and healing, and beauty and growth, and beauty and community.

Beauty is not a luxury, it is a fundamental cornerstone of a well-lived life.

“When our eyes are graced with wonder, the world reveals its wonders to us.”

Last week, I went to see my friend and physiotherapist, Christelle. Though I was there for foot issues, Christelle ended my session with a beautiful, relaxing cranial sacral massage of my head and neck. “It’s like getting an oil change for your car,” she said. “It refreshes your body and let’s you have a clean start.”

I was struck by her analogy and about how this relates to the role of beauty in our lives. Just like a head and neck massage might seem counter-intuitive for a hurting foot, the search for beauty may seem like a waste of time when you’re poor or heartbroken. And yet… one heals the other. The head is connected to the feet in ways that we don’t understand and the heart is connected to the eyes in ways that we don’t understand.

Seeking beauty is like getting an oil change for your heart.

I don’t have a daily meditation practice, and yet there is one thing I do at least once a day… I pause for beauty. Beauty is my meditation, my mindfulness practice, my oil change.

Beauty heals me. It helps me see the world differently. It connects me to the earth and to myself. It reminds me that God is with me, even in my darkest hour.

“Indeed, it is part of the disturbance of the Beautiful that her graceful force dissolves the old cages that confine us as prisoners in the unlived life. Beauty is not just a call to growth, it is a transforming presence wherein we unfold towards growth almost before we realize it. Our deepest self-knowledge unfolds as we are embraced by Beauty.” – O’Donohue

Sometimes, beauty comes to me as the frost pattern on my window. Sometimes it comes as a woodpecker on the tree in my backyard. And sometimes, like yesterday, beauty comes (after some toil and ugliness) in the form of a shiny clean refrigerator.

Whatever it looks like, beauty is worth pausing for.

by Heather Plett | Feb 25, 2016 | Uncategorized

This past weekend I went on a fun little road trip to Minneapolis with my three daughters. There were two moments from that trip that struck a cord with me:

1. I took my youngest daughter to see her favourite musician/Youtuber in concert. It wasn’t someone I had much interest in seeing, but she’s a little young to be in a music venue alone, so I bought an extra ticket and hung out at the fringes of the teenage crowd. Because this performer shared his coming out story quite publicly on his Youtube channel and now writes songs about that experience, he has developed a large following among GLBTQ youth. Probably at least half (maybe more) of the audience in the crowded room was from that community.

I was struck especially by three separate young men at the fringes of the room. They knew every word of every song and sang along with rapt attention. These were all young men who have probably spent much of their lives on the fringes – not finding a place of belonging because they don’t fit the stereotype of what a teenage boy is supposed to look like or who they’re supposed to fall in love with. And yet, in that room, they fit in and were accepted. They’d found a musician who was like them and therefore made them feel safe to be who they are. They belonged and they were witnessed.

It was a beautiful thing to witness – a space where teenagers who don’t normally fit in can find belonging. When the performer shared his coming out story from the stage, there was loud and prolonged applause. They were safe, they were affirmed, they weren’t the weirdos in the room.

2. My oldest daughter, a university art student, turned twenty while we were traveling, so in honour of her birthday, we spent much of Saturdayvisiting art galleries. In the Weisman Art Museum, there’s a unique interactive art installation that invites you through a doorway into the hallway of an apartment building. The hallway is silent until you lean on the apartment doors, and then you can hear what’s going on inside. There are six doors, and inside each one is a different soundscape. I was mesmerized and listened at every doorway.

Through one of the doors, the only sound is a woman weeping. That door was the most captivating to me and I could barely tear myself away. I was alone in the hallway for quite some time, so I stood leaning and listening. Though I knew it was only a recording on the other side of the door, I felt compelled to stand there and hold space for the woman’s tears, to bear witness to her grief even though she didn’t know I was there. Her tears represented so many of my own tears, so many of those times when I’ve cried alone behind a closed door.

Coming home with those two experiences reverberating in my heart, I am struck by the common threads that run through them…

There is inherent in all of us a longing for belonging, a longing to be witnessed.

Whether our stories are like those of the teenagers, seeking a space where they are not judged or ostracized, or like the woman (me) leaning on the door remembering her own lonely tears and how badly she wished someone had born witness to her in those dark moments, we long to be seen. We long to know we’re not alone, we’re not outsiders, we’re not locked away behind a door mopping up our own tears.

As I thought about those two moments, I was struck by another realization…

I have a responsibility to bear witness to others, to share my stories, and to let people know they are not alone. And you do too.

I am so grateful to that young performer who dared to speak his coming out story out loud. I am grateful that he found the courage to show those young people in the room that they are not alone in their fear, their isolation, and their “otherness”. I am grateful that, even in loud music venues, he is creating safety for young people to live authentic lives.

That’s the responsibility of each of us on this path to authenticity – to open our hearts to others, to bear witness to their pain, and to share the stories we feel called to share. Because when we share, we create safety for each other. We create belonging. We give them permission to be who they are.

Living authentically means living collectively. We make connections with each other through our shared stories and we find ways to heal together and create the more beautiful world our hearts are longing for.

Whether it’s the tears of grief and loneliness, or the fear of coming out, we all want to be seen.

****

One of the best ways I know of to be intentional about bearing witness to other people’s stories is to sit in circle with them. If you want to learn more about The Circle Way, I invite you to come to Winnipeg in May to join us in the circle.

by Heather Plett | Feb 17, 2016 | connection, growth, holding space, Intuition, journey, practice

“But it hurts if I open it too much.”

That’s what I hear, in some form or another, every time I teach my Openhearted Writing Circle or host openhearted sharing circles.

People show up in those places hopeful and longing for openness, yet wounded and weary and unsure they have what it takes to follow through. They want to pour their hearts onto the page, to share their stories with openness and not fear, to live vulnerably and not guarded, and yet… they’re afraid. They’re afraid to be judged, to be shamed, to be told they’re not worthy, to be told they’re too big for their britches. They’ve been hurt before and they’re not sure they can face it again.

And every time, I tell them some variation of the following…

An open heart is not an unprotected heart.

You have a right, and even a responsibility, to protect yourself from being wounded. You have a right to heal your own wounds before you share them with anyone. You have a right to guard yourself from people who don’t have your best interests at heart. You have a right to keep what’s tender close to your heart.

Only you can choose how exposed you want to make your tender, open heart. Just because other people are doing it, doesn’t mean it’s the right thing for you.

Yes, I advocate openhearted living, because I believe that when we let ourselves be cracked open – when we risk being wounded – our lives will be bigger and more beautiful than when we remain forever guarded. As Brene Brown says, our vulnerability creates resilience.

HOWEVER, that doesn’t mean that we throw caution to the wind and expose ourselves unnecessarily to wounding.

Our open hearts need protection.

Our vulnerability needs to be paired with intentionality.

We, and we alone, can decide who is worthy of our vulnerability.

We choose to live with an open heart only in those relationships that help us keep our hearts open. Some people – coming from a place of their own fear, weakness, jealousy, insecurity, projection, woundedness, etc. – cannot handle our vulnerability and so they will take it upon themselves to close our hearts or wound them or hide from them. They are not the right people. They are the people we choose to protect ourselves from.

Each of us needs to choose our own circles of trust. Here’s what that looks like:

In the inner circle, closest to our tender hearts, are those people who are worthy of high intimacy and trust. These are the select few – those who have proven themselves to be supportive enough, emotionally mature enough, and strong enough to hold our most intimate secrets. They do not back down from woundedness. They do not judge us or try to fix us. They understand what it means to hold space for us.

In the second circle, a little further from our tender hearts, are those people who are only worthy of moderate intimacy and trust. These are the people who are important to us, but who haven’t fully proven themselves worthy of our deepest vulnerability. Sometimes these are our family members – we love them and want to share our lives with them, but they may be afraid of how we’re changing or how we’ve been wounded and so they try to fix us or they judge us. We trust them with some things, but not that which is most tender.

In the third circle are those who have earned only low levels of intimacy and trust. These are our acquaintances, the people we work with or rub shoulders with regularly and who we have reasonably good relationships with, but who haven’t earned a place closer to our hearts. We can choose to be friendly with these people, but we don’t let them into the inner circles.

On the outside are those people who have earned no intimacy or trust. They may be there because we just don’t know them yet, or they may be there because we don’t feel safe with them. These are the people we protect ourselves from, particularly when we’re feeling raw and wounded.

People can move in and out of these circles of trust, but it is US and ONLY us who can choose where they belong. WE decide what boundaries to erect and who to protect ourselves from. WE decide when to allow them a little closer in or when to move them further out.

How do we make these decisions? We learn to trust our own intuition. If someone doesn’t feel safe, we ask ourselves why and we trust that gut feeling. Sometimes we’ll get it wrong, and sometimes people will let us down, but with time and experience, we get better at discerning who is safe and who is not.

We also have to decide what to share in each level of the circle, but that’s a longer discussion for another blog post. For now I’ll simply say…

Trust your intuition. Don’t share what is vulnerable in a situation that feels unsafe. Erect the boundaries you need to erect to keep your tender heart safe. Let people in who have your best interest at heart.

This article has been voluntarily translated into Farsi.

If you want to explore your own open heart, you’re welcome to join an Openhearted Writing Circle, or consider booking a coaching session. For a self-guided journey to your own heart, consider The Spiral Path, which remains open until the end of February.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my weekly reflections.

I have been sick this week, so I don’t have a lengthy reflection to share with you, but I thought I’d still take the time to offer one simple thought that came to me while I was in Vancouver.

I have been sick this week, so I don’t have a lengthy reflection to share with you, but I thought I’d still take the time to offer one simple thought that came to me while I was in Vancouver. The tree outside the window of my friend Lisa’s apartment wasn’t quite ready to burst open, so she drew me a map to make sure I’d get to see at least one tree in bloom before I went back home to the prairies. “Glorious magnolia tree” is what she wrote on the map, and I carried that map with me in search of beauty.

The tree outside the window of my friend Lisa’s apartment wasn’t quite ready to burst open, so she drew me a map to make sure I’d get to see at least one tree in bloom before I went back home to the prairies. “Glorious magnolia tree” is what she wrote on the map, and I carried that map with me in search of beauty.