by Heather Plett | Mar 16, 2017 | Community, Compassion, connection

Melancholy: a feeling of pensive sadness, typically with no obvious cause

That sounds about right for my state of mind this past week. I hesitate to call it depression, because it doesn’t feel that heavy, but there is definitely “pensive sadness” going on and it has no obvious cause.

When this familiar sense of melancholy comes at this time of year, I usually chalk it up to the end of winter, when I’m a little more sluggish from not taking as many long walks in the woods and not getting as much sunshine as I need. I get a little imbalanced when I lose my connection to the natural world. I’m pretty sure that it will pass soon (Spring always revives me), but for now, my creativity is low, my resilience isn’t what it normally is, my emotions are a little tender, and I feel disconnected. I stare at blank pages when I should be writing, I crawl into bed earlier than usual, I cry unexpectedly, and I watch too much Netflix.

A couple of things happened last week that were quite minor, but because of my state of mind, I took them more personally than I normally would. Though none of the people involved meant any harm, my tenderness left me feeling a little lonely and a little rejected. There was no true rejection involved (I still feel well loved by them), but in the middle of my fragility, it’s always easier to make up stories that align with how I’m experiencing the world. Feelings of disconnection often lead to greater disconnection.

Not long ago, I was on the other side of that story, inadvertently wounding someone who was going through her own state of tenderness. Unaware of her emotional state, I said something that normally would have been received with ease, but instead carried some wounding.

“At two, you’re at abstraction.” That’s a line from a Sara Groves song (that I think she borrowed from someone else, but I can’t find the source) that points to the impossibility of fully understanding another person’s reality. Another person’s pain, joy, love, trauma, history – they’re all just abstract concepts for us because we have never lived inside of them. We can never really “walk a mile in another person’s shoes”.

Despite our best efforts to be compassionate and understanding, our well-meaning words can land the wrong way and leave a person feeling wounded, lonely, misunderstood, defensive, angry, etc. That’s one of the reasons why, in our efforts to hold space for other people, we need to avoid falling into the trap of taking responsibility for their emotional response to our words or actions. Each of us is a sovereign individual with our own stories, our own interpretations, and our own emotions and when we take too much responsibility for another person, we diminish their sovereignty.

At a workshop a few weeks ago, Dr. Gabor Maté talked about how trauma can shape a person’s world and change the way they respond to stimuli. When a person grew up with trauma (either in the form of a traumatic event, or as a result of being raised by caregivers with unresolved trauma) their fight/flight/freeze instincts are heightened and they are inclined to over-react to stimuli that brings them back to their traumatic memories. Unresolved trauma, he said, makes it impossible for us to be in the present moment. “When we’re triggered, the emotions that show up are those of the abandoned child. We don’t react to what happened – we react to our interpretation of what happened based in our traumatic memory.”

Even compassionate people can inadvertently trigger someone’s trauma. Think about the last time you said something to another person that you thought was fairly innocuous and they reacted with defensiveness or anger that seemed out of proportion for the moment. There’s a good chance that there was something in what you said that triggered an old wound that they may not even know they still have. In that instant, that person was not the mature adult you thought you were talking to – they were a scared child relying on an instinctual response for their own protection. While they may need your empathy in that moment, and you might make a mental note to adjust your behaviour in the future to avoid triggering them further, you can’t take their autonomy away by trying to fix their problem for them.

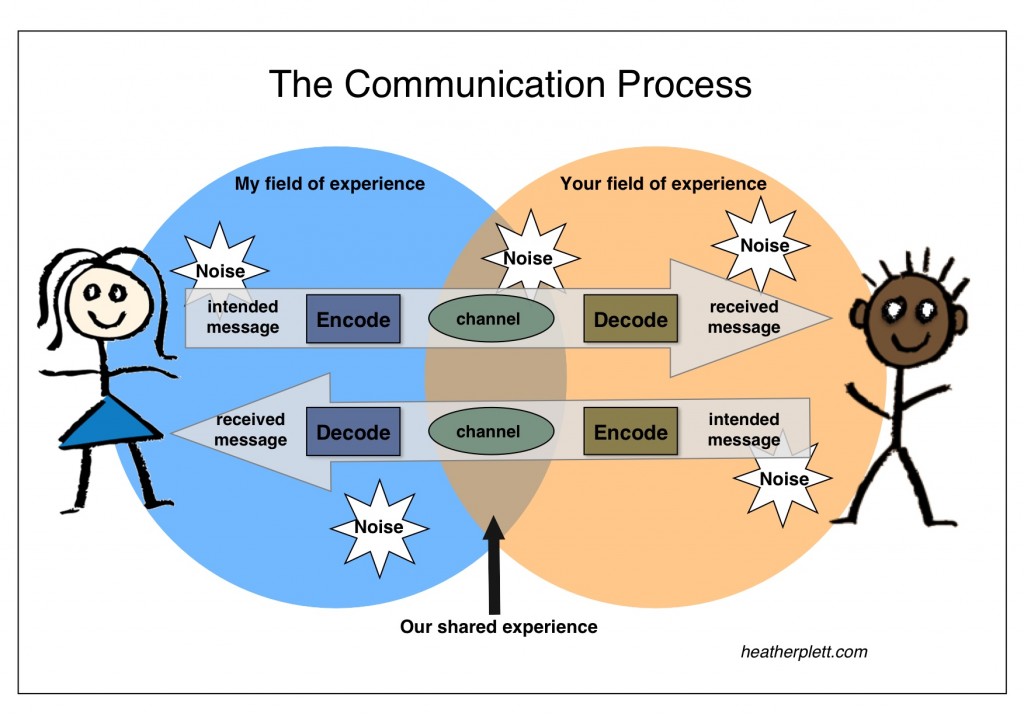

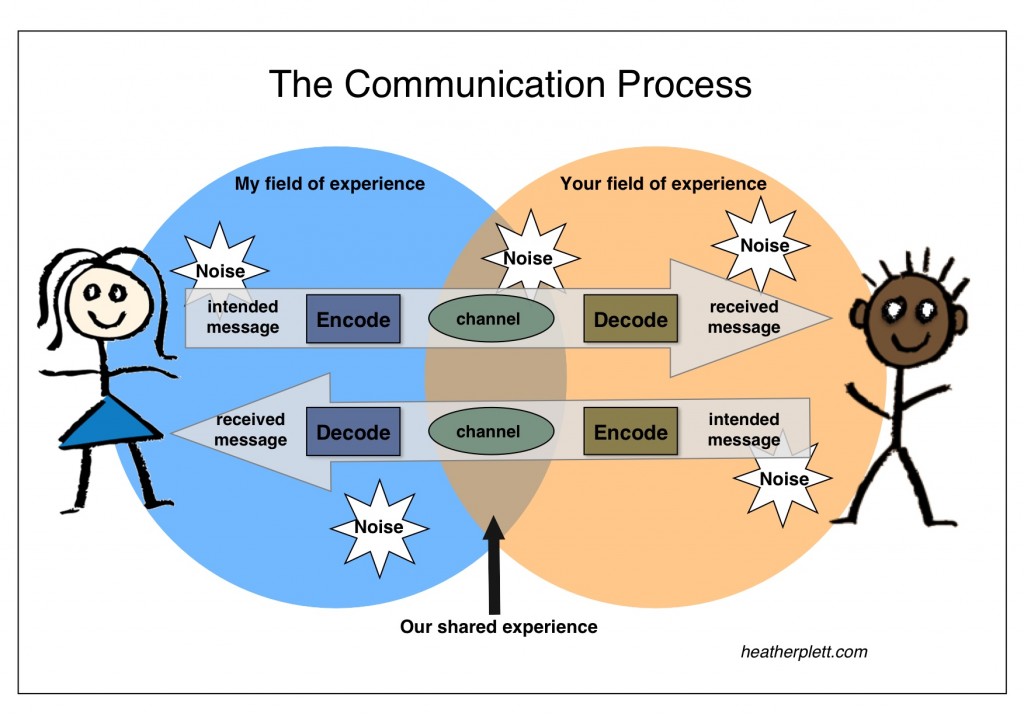

When I used to teach a university-level course in communication, I would always start with the following diagram to help my students understand that, in every communication, there are complexities and potential pitfalls that we can’t fully anticipate or mitigate.

(Note: this is my version of a popular model used in communication training, but I don’t know the original source.)

Each of us lives within a unique field of experience that may overlap with other people’s experience, but is never exactly the same. When I want to communicate with you, my intended message is shaped and encoded by my field of experience, which includes factors such as my gender, race, culture, disabilities, lived experiences, language ability, emotional state, etc.

I choose the channel of communication to best offer the message (ie. will I make a phone call, wait until I can talk to you in person, or send an email?). If I am compassionate, I will consider your field of experience when choosing the channel (ie. if you are hearing impaired, a phone call might not be the best method), but I’m limited in how much I can understand your reality so I may make mistakes. On top of that, no matter how carefully I encode the message and how intentional I am about the channel of communication, there is always unexpected noise that can disrupt or distract us at any moment in the process (ie. a child needing attention in the middle of a personal phone call, a disturbing story on the news, a misunderstanding, etc.).

The message crosses over to you and is, in turn, shaped and decoded by your own field of experience and your current circumstance. As I mentioned above, for example, you might be going through a period of tenderness that I had no way of knowing about when I initiated the communication. Even the most well-intentioned communication can go astray, and by the time you’ve decoded it, it may have a very different shape than what I intended. Much of our encoding and decoding processes happen in mere seconds during the course of a conversation, so we aren’t aware of all of what has shaped and reshaped what’s passed between us.

If you choose to engage in two-way communication, you send your own message across the reverse path, back through our fields of experience, risking similar misinterpretation, triggering, etc.

Given the potential complexity of even the simplest conversation, and given the fact that only a small portion of the process is within our control or within our conscious understanding, what can we do to improve the process? How can we be better communicators who wound others less often and receive fewer messages as wounds?

When you are the sender of the message:

• Pay attention to how your message is being shaped by your field of experience.

• Be humble, recognizing the limitation of your understanding of the other person’s field of experience.

• Especially where the differences are vast and there may be power imbalances, do your best to learn about the other person’s field of experience instead of passing judgement (especially if you are the one who holds more power).

• Be aware of the other person’s emotional response and check in when something doesn’t seem to land well, but don’t judge or try to control the emotion.

• Take responsibility for what you’ve said and allow the other person to take responsibility for their response.

• Allow for processing time in the conversation. Pauses may help to alleviate misunderstanding.

When you are the receiver of the message:

• Recognize the limitations that are at play in the sender’s lack of understanding of your field of experience.

• If you trust that the person will honour your current state of mind (ie. if there’s grief, depression, etc. going on), let them know that you may be limited in your capacity to receive.

• If you have a strong emotional response to the message, pause for a moment to check in with yourself. Recognize that the first reaction may be your instinctual desire to protect yourself and may not be fully based in the current situation.

• Hold the other person accountable for their words (especially in the case of harsh or oppressive language) and recognize when it may be in your best interest to stand up for yourself and/or walk away.

• If there is a misunderstanding and the relationship is important to you, reflect back to the person what your interpretation of the message is, based on your field of experience, and offer them an opportunity to reframe it.

• Take the time you need before sending a message back.

• Remember that you have a right to set boundaries and protect yourself.

Each situation is different, and based on how valuable the relationship with the other person is, you may or may not want to invest in the effort it takes to work through misunderstanding. If, for example, you’ve been verbally assaulted by a stranger at a bus stop, you probably won’t have any interest in figuring out how to communicate across your differing fields of experience. If, on the other hand, you love and trust the other person and believe that the relationship will be strengthened by deeper understanding, you’ll want to invest more time and energy in cutting through the noise.

*****

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my bi-weekly reflections.

by Heather Plett | Dec 8, 2016 | Community, Uncategorized

Yesterday, for the first time in the twenty-five years since I owned my first vehicle, I figured out how to change a burnt out lightbulb on my van’s turn signal. After that, I changed the broken windshield wiper. And in both cases, I’d bought the right ones for my vehicle and didn’t have to go back to the store to exchange them. Score!

When I finished, I wanted someone to celebrate with me, so I told my daughters. They have no clue what it feels like to be newly single at fifty and in charge of all of the little details of solo home/vehicle ownership and were suitably unimpressed. So I told my friends on Facebook and some of them understood and gave me virtual high fives.

There have been a lot of those small victories lately as I navigate this new terrain. I installed a set of closet doors earlier this week. And last week I built a small table, a large tray, and some shelves out of wood. A few months before that, I tore most of the flooring out of my house and learned to use a circular saw. All by myself! Huzzah!

These were all firsts for me. Nearly every time I’ve accomplished something new, I’ve looked for someone to celebrate with me. Sometimes I’ve texted friends, I’ve shared it on social media, or I’ve even found ways of bringing it up with strangers in the hardware store.

This may sound insecure – like I need someone’s validation to make me feel better about myself, but I don’t see it that way. Frankly, I felt great about what I’d accomplished even before anyone offered a response, so I didn’t need it, but I wanted it. Because celebration is better done in community.

It was celebration I was looking for – not validation.

Celebration is different from validation. Celebration elevates and encourages me, while validation encourages dependency. Celebration lets me know I’m not alone, while validation makes me feel like I can’t handle doing things on my own. If I need validation, it implies that I don’t know how to find my value without it. If, instead, I’m seeking celebration, it means that I want to be witnessed by my people because I honour the role they play in helping me to be courageous and strong.

Of course, there is a fine line between asking for attention/validation or showing off, and I don’t always know where that line is. And sometimes, when I’m feeling insecure, I step over that line. Plus each of us interprets it differently, based on our own set of internalized stories, so when I think it’s celebration I’m looking for, you might see it as validation.

Several months ago, after I’d given a keynote address to my largest audience ever, I shared my excitement on social media, and someone sent me a private message admonishing me for bragging too much. I felt hurt and I second-guessed myself. Was I bragging too much? Should I take the post down and celebrate my accomplishment all alone in my hotel room? No, I decided to leave it where it was and to allow those who wanted to give me a “woohoo!” to join in the celebration. This was my community, after all, and I need them in times of celebration just as I need them in times of struggle.

We get mixed up sometimes. We have a great fear of bragging and being “too big for our britches”, and so we keep our little victories to ourselves rather than inviting our dear ones into the celebration with us. And we let our fear spread to other people – we shame them for bragging so that they too will stay small and out of sight.

Living in an era of self-sufficiency and independence, we have become conditioned to fend for ourselves and act like we don’t need anyone.We’re not “supposed” to ask for too much support. We’re “supposed” to be able to accomplish great things without any support. We’re “supposed” to be self-confident enough to live out our dreams with nobody cheering us on.

I hear these words come out of my clients’ mouths sometimes. It’s not unusual for them to be a little embarrassed to speak of their accomplishments and their dreams. They talk about how they should be more self-confident and self-sufficient and should have the courage to do great things without other people’s support. Underneath, though, these is almost always a longing for the kind of community connections that will give them support and encouragement.

The self-help/coaching world has contributed to this individualistic mindset. We talk about “standing in our own power” but we don’t often talk about “standing in the power that is strengthened by community”. We talk about “creating our own destiny” and “detaching from other people’s opinion of us” but we don’t often talk about how our identity is intertwined with the people we’re in relationship with.

Self-sufficiency is a flawed ideal. We’re not really meant to be doing any of these things alone. We’re meant to live in community and to reach for each other in times of both celebration and grief. Because we are stronger and more courageous when we are together. We are more capable of personal growth and healing when we are in healthy relationships.

We NEED to need each other. We need community celebrations. We need to share our victories. We need to lend each other courage. We need to rely on each other’s strength.

Don’t get me wrong – I have great admiration for people who have the courage to do unpopular things because they believe in them even when nobody is on the sidelines cheering. AND I believe that we often let ourselves down when we don’t dare take a step before it is affirmed by others.

AND I also believe that when we do courageous or hard things, or even simple little things that make us feel good about ourselves, we’re meant to share our victories and allow others to celebrate with us.

Because when we celebrate together, the courage grows and spreads and the celebration galvanizes us to take even more bold steps.

So go ahead, let someone know the next time you do something you didn’t think you were capable of. Share your accomplishments and even your minor victories. Don’t attach your identity or value to whether or not they respond favourably (they’ve got their own stories going on, after all), but enjoy the celebration when they show up to support you.

And when you see others do the same, don’t shame them for bragging – put down your own baggage and celebrate with them!

by Heather Plett | May 10, 2016 | circle, Community

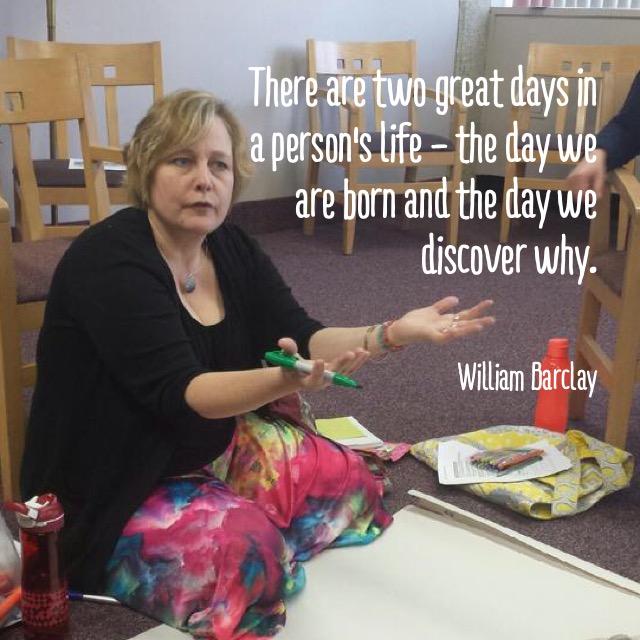

As I approach my 50th birthday, I am celebrating my “why”. The above picture is just that – me, in the middle of my “why”.

In the picture, I’m teaching from the floor. When we teach The Circle Way (as I did last week), we often teach from the floor. Rather than standing at a flip chart or chalk board at the front of the room, we kneel or sit on the floor inside the circle with a flipchart in front of us. Or we simply sit in the circle at the same level as everyone else.

Why is that important? Because we don’t teach from a place of hierarchy. We teach from a place of humility, a place of service. We teach from a place that demonstrates our own commitment to being in the learning with those we teach.

In that photo, I was talking about “the groan zone”, the place in the middle of a decision-making process when we feel like we’ve lost our way, but we’re really on the verge of bringing something new to life. (From The Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision Making.) I’ve spent a lot of time in the groan zone, and it’s because I have that I have found my why.

My why is found in teaching from the floor. My why is unfolding as I sit in the circle. My why is being a lifelong learner and sharing that learning from a place of humility. My why shows up when I practice holding space.

I teach from the floor because I believe in connection. I believe in deep conversations. I believe in community. I believe in the circle. I believe in confident humility.

Here’s an inspirational short video on finding your why.

If you want to find your why, I know what can help… The Spiral Path.

As I mentioned last week, I’m making a series of special offers this month so that you can celebrate my birthday month with me.

This week (and for the remainder of the month), I’m offering The Spiral Path to you at 50% off. So that you, too, can find your why.

To claim your offer, enter the following code into the coupon field on the registration page: birthday

Also, Mandala Discovery is still on for 50% off until the end of May. Same instructions – use the coupon code: birthday.

You can get two of my courses for the price of one!

And next week, I’ve got a brand new offering that I can hardly wait to share with you!

by Heather Plett | Apr 18, 2016 | Community, connection, Uncategorized

I wrote a very personal post recently for The Helpers’ Circle about how much I struggle with The Fear of Letting People Down (and how I’ve learned to talk myself out of it). Here’s a quote from that post…

“My Fear of Letting People Down started at a young age. I became very practiced at being The Good Girl, the one who didn’t show her anger, who took responsibility for her work and did it well, who didn’t rock the boat and who could be depended on at all costs. I needed people to be happy with me – to notice my good work and to not get angry. When people were pleased with me and nobody was angry, my world felt safe.”

After writing it, I was thinking about how many things get in the way of our quest for authenticity – fear, shame, duty, etc.. In almost every conversation I have, whether in coaching sessions or workshops, I hear a deep longing for greater authenticity, and almost always a deep sadness that the path to authenticity seems so treacherous and never-ending. And the fear always keeps us company… the fear of letting people down, the fear of embarrassing ourselves, the fear of rejection, the fear of judgement, the fear of falling flat on our faces, and the fear of being alone.

We want to be real. We want to be true to ourselves. We want to be bold in being who we truly are. And yet… so much gets in the way that sometimes it seems impossible. There are bills to pay, people to please, rules to follow, wounds to protect, and shame to hide.

Why is that the case? Why have we found ourselves in a culture that is so hell-bent on making people live inauthentic lives?

I don’t think there’s a straightforward answer to that question. It’s probably a nature+nurture thing. At least some of it can be connected to the materialistic lifestyles we’ve adopted – a function of living in a production-oriented, economy-driven world. Shiny things are the most desirable, and so we make ourselves more shiny.

But there’s also something else, and it’s about love.

Not long after I wrote the piece for The Helpers’ Circle, I interviewed my friend Lianne Raymond (who knows a great deal about psychology and child development) for one of the monthly interviews I’m sharing in the circle and Lianne said something quite profound that cracked open something new for me in this regard.

“Given a choice between authenticity and love, a child will always choose love.”

Wow. She’s right! That’s where it all begins! From the very first time we open our eyes and seek out our mothers’ smiles, our primary quest is for love. Love is the foundation – the ground we learn to walk on. From the moment we slipped out of the womb (and before), we needed it nearly as much as we needed the air we breathed. We did everything we could to get that love, even if it meant gradually giving up pieces of ourselves to please the person whose love we sought.

A world in which we were loved is a world in which we are safe.

Even good parents and guardians can unintentionally attach behaviour to love. I remember my own mother (who did so many things right) used to say things like “if you love me, you’ll wash the dishes”. And though I haven’t used those same words, I know there are moments I unintentionally make it clear to my daughters that it’s easier to love them when I see certain behaviour. We are all flawed in this effort to love each other.

Whether it was to please our parents, our teachers, or our peers, we quickly learned, as children, what behaviour brought us the most love and what behaviour resulted in that love being withheld. We adapted, we conformed, and we sacrificed. Some of us never really got the love we were seeking, and so the world became a very unsafe place. We didn’t know how to behave because nothing we did brought us the love we so badly needed.

Somewhere along the way, we forgot what it meant to be real. We only knew what pleased or displeased the people whose affections we craved. And some of us, raised in volatile or unstable environments, knew how to run for cover or to morph ourselves into whatever shapes would best protect us.

Then one day we grew up and didn’t recognize ourselves anymore. We saw only strangers looking back in the mirror at us. We realized that, instead of being authentic, we had become composites of all of the behaviours that other people expected of us.

To reveal the real work of art, hidden under the collage of other people’s expectations, takes a lot of courageous effort. Every layer we peel away reveals a tenderness, a shame, a wound. Every step we take to recovering our authenticity puts us at risk. We may be shamed for it, we may be rejected, we may not be loved. The little child in us shrieks “YOU CAN’T DO THAT! You’re breaking the rules! You need to be loved! You need to be safe!”

But “safe” begins to feel like “stuck” and we long for more. We long for truth. We long for freedom. We long for ourselves.

Gradually, those of us who finally decide that authenticity is the only way we can truly live, realize that we have no choice but to break the rules. We have no choice but to risk being unloved. We have no choice but to give up the safety we worked so hard to find.

After much agony, fear, and faltering, those of us who find the courage come back to ourselves. Many of us lose people along the way – we lose those people who only know how to love us when we behave in a certain way. But we find other people. We find people who are on similar paths to authenticity and we realize that we can cobble together new families and new communities that hold space for us no matter how we behave.

Finally, we find a new kind of safety – one that is rooted in real love, not conditional love – and in that place of safety, we unfurl into whoever we are meant to be.

It may never be perfect (even now I sometimes find myself hiding parts of myself from those whose love I value most because I don’t want them to reject me), but it feels a little closer to being Real.

* * * * * *

p.s. To see the interview with Lianne or to read the post I mentioned, about The Fear of Letting People Down, you’ll have to become part of The Helpers’ Circle.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my weekly reflections.

by Heather Plett | Jan 5, 2016 | Community, connection

In one of my favourite childhood photos, I’m sitting on the couch with a row of dolls lined up on my lap. Unfortunately, that photo was lost when my mom moved away from the farm after dad died, so it exists only in my memory now. The way my memory serves me, though, each of those dolls has a different skin colour, hair colour, and/or cultural attire. Only one of those dolls has blonde hair and blue eyes like me.

That’s the way I like to think of myself – from a young age choosing to surround myself with difference, with diversity. It’s not always true (in much of my life I have been surrounded by too much sameness), but it’s my ideal image of myself.

I thought of that photo recently when a viral video depicted two young white girls reacting in disappointment and disgust when they received black dolls as Christmas gifts. What’s most disturbing about that video is the way the adults giggle about and invite their reaction and the very fact that some adult thought it was funny enough to share online. Clearly their behaviour is a learned behaviour. Raised in another environment, those girls would likely have been delighted by the gift.

I have been disturbed lately by sameness and the way those girls’ actions too closely reflect our own. I see it in my own life and I see it in the world around me. We gravitate toward what is comfortable and safe, what looks and sounds like us, and so we end up in places, in conversations, and in friendships where there is a clear insider and a clear outsider. In doing so, we marginalize the people who don’t fit in. Without even knowing it, we toss aside the black dolls just as those young girls did.

Most of us are good people, so we don’t do it intentionally, but good people make mistakes when we don’t pay attention. Good people make mistakes when we see the world only through our own lenses.

Marginalized people get hurt by a lot of good people who “didn’t mean to hurt anyone”.

Let me be perfectly clear that I include myself in this critique. I like to be comfortable as much as the next person, and so I too often find myself in places and in relationships where the people in the room largely fall into the same racial, gender, and socio-economic categories as I do.

But we miss out on SO MUCH when we don’t listen to the voices of people who are different from us. We miss out on SO MUCH when we don’t challenge our own comfort levels and dare to stretch ourselves beyond what feels safe. We miss out on SO MUCH when we toss aside the beautiful black dolls.

When everyone in the room looks the same, someone’s left outside. Sometimes that’s okay (when we’re at a family gathering, or when we’ve come together for healing or empowerment, for example), but often it’s not.

Over the festive season, I participated in two spiritual gatherings. The first one (which I’ve written about before) was a small gathering in a hospital sanctuary, where people of diverse faiths each lit a candle and talked about what light means in their spiritual tradition. At that one, the room was full of diversity of every kind. Not only were there at least nine faith groups represented in those who lit candles (most of whom were people of colour from various parts of the world), but there were hospital patients in wheelchairs and people of all walks of life, with varying degrees of health, socio-economic status, and physical ability.

I left that gathering feeling energized and connected to God/dess.

The other gathering I attended was on Christmas Eve, in Florida where my family was vacationing. This was a traditional Christian service that was fairly similar to what I grew up with. Though the setting was very different (this was a large posh church with theatre-style seating, while I grew up in a tiny and poor country church with old wooden pews), the language was largely the same. There was some comfort in that sameness – I knew the Christmas carols and had heard the Christmas story hundreds of times. It was a perfectly lovely service, with great singing and good story-telling on the pastor’s part. One story he shared was quite moving – about how a large endowment to the church had been split up among church-goers who were told to go out and do some act of kindness in the community.

Unlike the gathering in the hospital sanctuary, there was very little diversity in the room. In a room filled with more than a thousand people, I saw only three people of colour and could see evidence of very little socio-economic diversity. Among the visible leadership, there was even less diversity. The only people who spoke or served communion were older white men. Either you received God’s teachings and God’s body and blood from an older white man, or you didn’t receive it at all.

I left that gathering feeling weary and disconnected from God/dess.

I have no doubt that the church-goers and their leaders are good people doing good work in their community. They don’t mean to exclude anyone, and there’s a good chance they have well-meaning conversations about how to increase their diversity and how to reach out to people who are different from them. I know many good people like them, and in many ways, I am one of them – good people trying to do good things.

But good people hurt other people by living their good, comfortable lives and ignoring their own privilege and narrow views of the world.

And this is not a domain that’s exclusive to a conservative Christian church by any means. It happens in all kinds of settings.

Recently I was looking at an online advertisement for a women’s leadership summit – the kind of event I’d normally be drawn to, where leadership is seen through a feminine lens and there’s a comfort level with talk of the feminine divine and women’s power. But there was something about it that left me feeling sad, and I realized it was because of the sameness of the images on the speakers’ list. All of them were white women between the ages of 30 and 50 who looked like they’d stepped out of the pages of a yoga magazine.

Just what the patriarchy has for so long done to them, the organizers of this online summer were, (inadvertently of course) doing to others – marginalizing the voices of those who don’t fit. I’m sure these women would have all been horrified by the video of the young white girls tossing aside the black dolls, but in a way, the result was the same.

Sameness. Comfort. Marginalization. Barriers. Disconnection.

What do we do about it? That’s a big conversation and it needs the voices of many people who see the world differently from me.

I can only offer my own perspective from where I stand.

We start by noticing. We start by paying attention – looking around the room to see who’s sitting with us, checking our social media feed to see who we’re conversing with, noticing the books we read and the voices we listen to, paying attention to who has a voice at our gatherings. Because if we’re not listening to the stories of people who are different, if we’re not sitting and having conversations with them, we’ll always be stuck in this same place.

I loved Gloria Steinem’s recent book, My Life on the Road, largely because she shares so many stories about how she was influenced and changed by the people she met on the road. Much of her wisdom came not from people who look like her, but from black people, indigenous people, bikers, and farmers. She is the woman she is today because all of these people’s stories have been woven into her own.

I’m here to challenge us all to live more like that. Let’s be the kind of people who listen to stories and wisdom of people who look, think, and live differently from us. Let’s read books from other parts of the world and written by people of other races and classes. Let’s have more conversations with people who don’t share our political views or our socio-economic status.

I’ve created a list of books written by people who’ve lead very different lives from mine that I want to read and I’m working my way through them. Some I’ve read recently and recommend are Wab Kinew’s The Reason You Walk, Rosanna Deerchild’s Calling Down the Sky, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah. I encourage you to build your own list.

I’ve also signed up for a course called “How to Embrace Diversity to Improve your Business” being offered by Desiree Adaway and Ericka Hines. Quite frankly, there is still too much sameness in the kind of clientele I attract and I want to see what I can do to change that. I know that Desiree and Ericka will challenge me and hold me accountable, and though it may be uncomfortable sometimes, I’ll do my best to stretch myself.

What else can we do to shift the status quo? Good people, I look forward to hearing from you.

by Heather Plett | Nov 25, 2015 | Beauty, change, Community, Compassion, connection, Friendship, grace, growth

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the importance of finding your tribe – people who love you just the way you are and who cheer you on as you do courageous things.

Tribe-building is important and valuable, but it only takes you part way down the path to an openhearted life.

This week, I’ve been contemplating what we should do with the people outside of our tribes.

It’s cozy and warm inside a tribe, and the people are supportive and non-threatening, so it’s tempting to simply hide there and close off from the rest of the world. When you’re hurting, that might be the right thing to do for awhile – to protect yourself until you have healed enough to step outside of the circle.

But the problem with staying there too long is that it creates a world of “us and them”. When you stay too close to your own tribe, it becomes easier and easier to justify your own choices and opinions and more and more difficult to understand people who think differently from you. Before long, you’ve become suspicious of everyone outside of your tribe, and when their actions threaten your way of life, you do whatever it takes to protect yourself. Fear breeds in a closed-off life.

Last week, I knew it was time to challenge myself to step outside my tribe. I’d been playing it safe too much lately, so when I saw a Facebook posting for an open house at the local mosque, I decided that was a good place to start. I shared the information with friends, but chose not to bring anyone with me. Bringing friends with me into unfamiliar territory makes me less open to conversations with people who are different from me and I didn’t want that – I wanted to go in with an open, unguarded heart. That’s one of the reasons I’ve learned to love solo traveling – it’s scary at first, but it opens me to a whole world of new opportunities and friendships that don’t happen as naturally when I’m hiding behind the safety of a group.

I have traveled in predominately Muslim parts of the world and have always been warmly received, so I knew that the open house would be a pleasant experience. It turned out to be even more pleasant than I’d expected.

First there was Mariam, a young university student who served as tour guide to me and a small group of strangers. Mariam’s easy smile and warm personality made us all feel instantly comfortable. She lead us through the gym to the prayer room and told us why she’s happy that the women pray in a separate area from the men. “I want to be close to God when I pray, not distracted by who might be looking at me or bumping into me.” Before the tour was over, Mariam hugged me twice and I felt like I’d made a new friend.

First there was Mariam, a young university student who served as tour guide to me and a small group of strangers. Mariam’s easy smile and warm personality made us all feel instantly comfortable. She lead us through the gym to the prayer room and told us why she’s happy that the women pray in a separate area from the men. “I want to be close to God when I pray, not distracted by who might be looking at me or bumping into me.” Before the tour was over, Mariam hugged me twice and I felt like I’d made a new friend.

Then there was the grinning young man at the table by the sign that read “your name in Arabic”. His name now escapes me, but I can tell you he never stopped smiling through our whole conversation and was one of the friendliest young men I’ve met in a long time. He told me, while he wrote my name, that he’d learned some of his Arabic from cartoons. Growing up in Ontario, he’d preferred Arabic cartoons to Barney or Sesame Street.

At the “free henna” table, I met Saadia, who moved here from Pakistan three years ago because she and her husband wanted to give their children a better chance at a good education. Her husband is a doctor who’s still trying to cross all of the hurdles that will allow him to practice in Canada. Before our conversation was over, Saadia had given me her phone number in case I ever want to invite her to my home to give me and my friends hennas.

What struck me, as I left the mosque, was how much grace and courage it takes, when your people have become the object of racism, fear, and oppression, to open your hearts, homes, and gathering places to strangers. Instead of hiding within the safety of their own tribe and justifying their need for protection and safety from others, the local Muslim community threw their doors and hearts open wide and said “let’s be friends. We are not afraid of you – please don’t be afraid of us.”

I experienced the same grace and courage among the Indigenous people of our community last Spring after we were named the “most racist city in Canada”. Instead of retreating into the safety of their tribes, they welcomed many of us into openhearted healing circles. Instead of being angry, they taught us that reconciliation starts with forgiveness and the courage to risk friendships across tribal lines.

I will be forever grateful to Rosanna, who invited me to co-host a series of meaningful conversations with her, to Leonard who handed me a drum and welcomed me to play in honour of Mother Earth’s heartbeat, to Gramma Shingoose who gave me a stone shaped like a heart and shared the story of her healing journey after a childhood in residential school, to Brian who welcomed me into the sweat lodge, and to many others who opened their hearts and reached across the artificial divide between Indigenous and settler.

The more I’ve had the privilege of building friendships with openhearted people whose world looks different from mine, the bigger, more beautiful, and less fearful my life has become.

This week, I’ve read Gloria Steinem’s memoir, My Life on The Road and there is so much in it that resonates with the way I choose to live my life. It’s a beautiful reflection of how her life has been changed by the people she has encountered while on the road. “Taking to the road – by which I mean letting the road take you – changed who I thought I was. The road is messy in the way that real life is messy. It leads us out of denial and into reality, out of theory and into practice, out of caution and into action, out of statistics and into stories – in short, out of our heads and into our hearts. It’s right up there with life-threatening emergencies and truly mutual sex as a way of being fully alive in the present.”

Another quote speaks to how much broader her thinking has become because of her encounters on the road. “What we’ve been told about this country is way too limited by generalities, sound bites, and even the supposedly enlightened idea that there are two sides to every question. In fact, many questions have three or seven or a dozen sides. Sometimes I think the only real division into two is between people who divide everything into two and those who don’t.”

We don’t have to spend as much time traveling as Gloria Steinem does in order to live this way – we simply have to open our hearts to the people and experiences in our own communities that have the potential to stretch and change us and lead us past a life with only two sides. Sometimes a conversation with the next door neighbour is enough to help us see the world through more open eyes.

* * * * *

p.s. Would you consider supporting our fundraiser to sponsor a Syrian refugee family?

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.