by Heather Plett | May 29, 2015 | circle, courage, growth, journey, Labyrinth, Uncategorized

“Do you wish to be great? Then begin by being. Do you desire to construct a vast and lofty fabric? Think first about the foundations of humility. The higher your structure is to be, the deeper must be its foundation.” – Saint Augustine

Since returning from my trip to Whidbey Island on Monday, I have been trying to come up with at least a few words to describe my time away. I haven’t been very successful, though. If you’re following me on social media, you might have noticed an uncharacteristic silence of late. It’s hard to say in 140 characters or less what I can’t even describe in a blog post or conversation.

Some experiences are two deep for words.It was one of those life-changing, heart-opening, paradigm-shifting trips.

I was on Whidbey Island for two purposes – a.) to work with a small circle of people on a new website for The Circle Way, and b.) to replenish myself and dive into my writing at Self as Source of the Story, a retreat facilitated by my mentor, Christina Baldwin.

I was on Whidbey Island for two purposes – a.) to work with a small circle of people on a new website for The Circle Way, and b.) to replenish myself and dive into my writing at Self as Source of the Story, a retreat facilitated by my mentor, Christina Baldwin.

Both of those experiences were dreams come true. I am working and learning and building things with my mentors and friends, and finding my way on the very path I first started dreaming about fifteen years ago. It’s been an incredible journey, learning to trust the nudgings and whispers along the way, gaining resilience in the hard parts, and trying to be patient in the slow parts.

If you’re hanging onto a dream that just won’t let you go, take heart – it may be slow in showing up, but that doesn’t mean it’s not coming. Keep your heart focused in the right direction, and life may some day surprise you with its abundance and grace.

The entire trip felt like a divinely-offered gift, and there are many parts of it that feel tender and fragile and that I need to hold close to my chest right now rather than share. Some day they will become part of my storytelling, but not yet – not until they are full grown and well processed and strong enough to stand on their own. (In a few months, you have permission to ask about the frog that showed up on my 49th birthday and the gold key that came to me in the labyrinth.)

The biggest lesson of the trip was this…

Authentic living is like scuba diving. Just when you get comfortable diving to a certain level, you’ll become curious about what the sea looks like further down and you won’t be able to rest until you get there. Soon you’ll be developing the lung capacity and looking for the equipment to take you deeper.

During Monday’s closing circle at the writing retreat, I said “I’ve been a writer long enough to know that every few years I’ll be invited into an even deeper understanding of and connection with my own voice. I just didn’t know how deep this week was going to take me.” This statement doesn’t only apply to writers – it applies to anyone on a personal/spiritual journey. We are always invited to go deeper.

I’d started the retreat with one goal in mind – to gain some clarity about the book I finished nearly three years ago. Some of you who’ve followed me for awhile know that I was working on a book about how the three weeks leading up to and including the birth and death of my son Matthew changed my life. I thought I was finished that book three years ago. I was in the process of editing it when my Mom was diagnosed with cancer.

Mom’s death changed the story. Not only did my grief make it difficult to re-enter the story of my short relationship with Matthew, it changed the very fabric of what I’d put on the page.

Several times since then, I’ve taken it off the virtual shelf and tried to revisit it, but there was always resistance. I didn’t know how to bring it to completion. I hadn’t found the right equipment or developed the lung capacity for the deeper dive.

By the time I got to the retreat, I was ready to simply put it away and allow it to be part of my own personal growth and never have it published. But I opened myself to the possibility that the story wasn’t finished yet. It wouldn’t leave me alone.

In the very first writing prompt at the retreat, I cracked the story open again. Instead of putting it onto the shelf, I was invited into a deeper understanding of it. A new voice showed up on the page. Or rather – an old voice showed up – an old voice that wanted to weave itself into mine. This old voice had always been there, but I hadn’t known how to tap into it before. It took the right container, the right intention, an open heart, and a few simple words from my mentor to crack it open.

That’s the lesson I want to leave with you today… Your personal work is never done. You will always be invited to go deeper.

I don’t know what your version of “deeper” will look like, but I know that if you create the right container, find the right circle of support, and let yourself be guided by the right mentor(s), you’ll be invited into deeper and deeper self-awareness and deeper and deeper trust in your own voice.

This deep diving doesn’t happen by accident, however, and it doesn’t happen at the fringes of our overly-busy lives. We have to be intentional about it, create space in our lives to invite it in, and seek out the people who will lovingly hold space for it. We have to seek out the equipment and do the practices that increase our spiritual lung capacity.

Throughout the week, I did the work to invite this deeper voice more fully into my life and work. I walked the labyrinth several times, I spent a day in silence, I had deep and personal conversations with like-minded people, I wandered the woods, I sat in circle and listened to other people’s stories, and I wrote pages and pages in my journal. I also shed a lot of tears and let some of my fears hold court until they felt adequately heard and were willing to let me move on.

Throughout the week, I did the work to invite this deeper voice more fully into my life and work. I walked the labyrinth several times, I spent a day in silence, I had deep and personal conversations with like-minded people, I wandered the woods, I sat in circle and listened to other people’s stories, and I wrote pages and pages in my journal. I also shed a lot of tears and let some of my fears hold court until they felt adequately heard and were willing to let me move on.

Our deeper voices have to be tended well. They don’t show up by accident and they’ll go back into hiding if we don’t create space in our lives to foster them. They are easily swayed by fear and easily ignored by long to-do lists, unless we give them priority attention.

If you feel that you are being invited into the next layer of depth, be intentional about creating space for it.

- Go on a retreat that’s long enough for the work you need to do

- Spend an hour each day with your journal and your spiritual practices,

- Find a coach or mentor who will ask the right questions,

- Gather like-minded people into circle, and

- Guard the parts of the story that feel tender and fragile. (Only share those parts with your most trusted confidantes – people who can be trusted to help you nurture them.)

If you need some support, consider joining The Spiral Path: A Woman’s Journey to Herself (starts June 1st). Or sign up for one of the remaining spots in the Openhearted Writing Circle (online on June 6th). Or learn to Lead with Your Wild Heart. (Note: At this time, I am not accepting new coaching clients, but will open the door again in September.)

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | May 1, 2015 | Community, growth, journey, Uncategorized

“If we can share our story with someone who responds with empathy and understanding, shame can’t survive.” – Brené Brown

I like fruity tea. Passionate peach, blueberry bliss, raspberry riot – you name it, I probably like it. But at some point in my life, I picked up the idea that fruit teas aren’t for REAL tea drinkers. In the hierarchy of teas, I imagined them stuck at the bottom, the uncoolest of the hot beverages.

I have no idea where I picked up on that tea story. Perhaps someone made fun of me for my tea choice. Perhaps it was just a vibe I picked up. Perhaps I made it up myself. However I picked it up, I let it affect my tea choices. For years, I was afraid to drink fruity tea in public, afraid that the real tea drinkers might notice and judge me for it.

Silly, isn’t it? But isn’t that how most of our shame stories are – rather foolish, once brought into the light of day?

To be honest, some of my shame stories around food choices are rooted in being raised poor, on a farm, and as part of a small Mennonite subculture that kept itself somewhat apart by not engaging in all of the activities (ie. Fall suppers where I might have been exposed to other kinds of tea) in our community. We didn’t have access to “fancy” foods, and so, when I became an adult and was faced with choices that I wasn’t used to, I was afraid I would choose the wrong thing and people would discover how uncultured I was. I was ashamed of being uncultured – ashamed of being a Mennonite farm kid who wasn’t as sophisticated as I assumed the city kids of more worldly-wise cultures were.

We pick up shame stories for a lot of different reasons. Some of them have clear origins (like parents who made us believe we were shameful) and others can only be understood after years of excavation and personal work. Some are relatively easy to release (I now drink fruity tea in public when I want to) and others have become so imbedded into our identity, they become part of our DNA (like the shame around cultural/racial identity).

We inherit many of our shame stories from the generations that came before us in our lineage. Those are the ones that become particularly imbedded into our identity.

After spending several years working in international development, and then a few years on the board of a feminist organization, and now as part of a team doing race relations conversations, I’ve noticed a pattern about cultural shame. Though shame is common to all cultures, it has a particularly strong hold among oppressed cultures.

One of the greatest weapons of oppression is shame. When oppressors manage to inflict shame on people, they increase their own power and diminish the ability of those they oppress to rise up out of their oppression. Shame diminishes courage and strength.

Ironically, though, many of the shame stories related to oppression are passed down not directly from the oppressors themselves but from those above us in our lineage who have been oppressed before us – not because they want to oppress us, but because they want to protect us.

We pass the stories of oppression down to those we most want to protect. When we inherit them as young children, though, those oppression stories become shame stories.

In the book “The Shadow King: The invisible force that holds women back“, Sidra Stone teaches that we adopt the inner patriarchy (the voice that tells women that they are not worth as much as men) from our mothers. It is primarily our mothers who teach us how to stay small, how to please the men, how to avoid getting hurt, and how to give up our own desires in deference to others in our lives (especially men). They do it to protect us, because that’s the only way they’ve learned to protect themselves. And so it goes, from generation to generation, each mother passing down to her daughters the stories of how they can stay safe.

Last week, many of us watched the video of a Baltimore mother who beat her son in public when she found him among the protestors. Desperate to protect him, she pulled him away from enemy lines and taught him, by her own raised hand, that he must learn to submit or risk being killed.

The problem is that those of us growing up in environments where we’re learning these stories from our parents do not yet have a reference point to understand generations of oppression. The only way we know how to interpret our parents’ attempts to keep us small and silent is to believe that they will stop loving us if we become too large and vocal. We become convinced that we are worthy of shame and not love. Though that mother in Baltimore may tell her son a thousand times that she did it out of love and a desperate need to protect him, I suspect there will always be a small child inside him who will believe “my mother shamed me in public, therefore I am worthy of shame.”

Remember the experiment with the monkeys, where a beautiful bunch of bananas hung above a ladder, but every time a monkey would climb to get the bananas, all of the monkeys in the cage would be sprayed with water? Not wanting to be sprayed, the monkeys kept pulling down any monkey who attempted to climb the ladder. Even after all of the monkeys were replaced (one by one) and nobody had experienced the spraying, they still kept any new monkey from climbing the ladder, because they themselves had been stopped. Those new monkeys (if they think like humans), not knowing the history, probably believed “I have done something wrong and my tribe is ashamed of me. I must not be worthy of happiness.” And then they passed the story down to the next generation, pulling down anyone who dared to climb the ladder.

Growing up with the shame inflicted by generations and generations of shamed people, we forget that it is not the lack of love they had that caused them to pass this down to us, it is their wounded love that meant they didn’t know how else to protect themselves and us from further wounding.

And, remarkably, it’s not only psychological – it becomes planted in our very DNA. Studies have shown that trauma has changed people’s DNA and that that DNA has been passed down to subsequent generations, showing up as irrational fear and the tendency to be triggered even if they didn’t directly experience that trauma. If trauma can be passed down through DNA, I’m fairly certain that shame can too, since trauma and shame are often closely linked.

How do we heal these generations of wounds? That is something that I’m just beginning to explore and read about (as are many others) and I welcome anyone’s thoughts, ideas, or experience.

I know that it must be a holistic response, involving body, mind, and spirit. In The MindBody Code, Mario Martinez talks about how we have to heal the shame in our bodies as well as our minds. He teaches contemplative embodiment practices that help replace the shame stories with honour stories.

I also believe that healing shame involves dancing, singing, art-making, spiritual practices, and lots of touch. We can’t heal shame with simply left-brain, logical thinking – we have to engage in creative, right-brain spiritual meaning-making. It helps to create rituals (ie. painting the shame monsters and then painting safe places for them to be exposed), embody our healing (ie. dancing our way into courage), and find spiritual practices that teach us to let go and trust (ie. mindfulness meditation).

And, more than anything, I believe that healing happens in community. Ironically, we pick up our shame through our relationships and we heal it through healthier relationships. That’s the nature of community – it comes with both the good and the bad, the wounding and the healing. In order to heal, we have to find safe community in which we can be vulnerable without fear. When we expose our shame stories among those who hold space for us, the shame loosens its power over us. Intentional circle practices are the best practices I know of for this kind of work.

Happily, there have also been studies that demonstrate that those changes to the DNA can be reversed, so there is hope for the generations that come after us if we do our work to heal. Shame is not the end of the story. We can heal it for ourselves and future generations.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Mar 4, 2015 | art of hosting, circle, Uncategorized

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

If you want to make a tasty soup, you don’t throw your ingredients onto the stove and hope they somehow transform themselves into a soup.

Instead, you choose the right container that will hold all of the ingredients and allow room for the soup to boil without bubbling over onto the stove. Then you begin to add the ingredients in the right order. First you might fry onions and garlic to bring out their best flavour. Then you add the right amount of soup stock. And finally the vegetables and/or meat are added according to how long each ingredient takes to cook. If you want to make a creamy or cheesy soup, you add the dairy only after everything else has cooked and the soup is no longer at a full boil.

Through this intentional and careful act of creation, you allow the flavours to blend and layer into a meal that has the potential to be greater than the sum of its parts.

The same is true for a meaningful conversation.

If you want to gather people to talk about something important, you don’t simply throw them together and hope what shows up is good and meaningful. Sure, sometimes serendipity happens and a magical conversation unfolds in the most unexpected and unplanned places, but more often than not, it requires some intention to take the conversation to a deeper, more meaningful level.

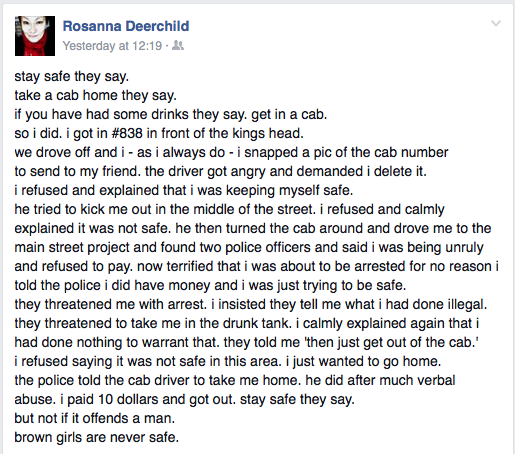

Take, for example, the recent community conversation on race relations that Rosanna Deerchild initiated and I facilitated. If we had simply invited people into a common space for a meal without giving some thought to how the conversation would flow, people would have stayed at the tables where their friends or family had gathered, conversations would have stayed at a fairly shallow level, and we wouldn’t have gotten very far in imagining a city free of racism. Instead, we moved people around the room, mixed them with people they’d never spoken with before, and then asked a series of questions that encouraged storytelling and the generation of ideas. Through a process called World Cafe, we arranged it so that everyone in the room would end up in small, intimate conversations with three different groups of people. We followed that up with a closing circle. (Stay tuned for more idea-generating conversations such as this one in the future.)

Especially when the subject matter is as challenging as race relations, the quality of the conversation is only as good as the container that holds it.

If you try to cook soup in a plastic bowl, you’ll end up with a melted bowl and a mess all over your kitchen. Similarly, if you try to have a heated conversation in a container not designed for that purpose, you run the risk of doing more harm than good.

The same is true for our Thursday evening women’s circle. We could have a perfectly lovely time gathering informally to talk about our families, our jobs, and our latest shopping trips, but if we want to have the kind of intimate, open-hearted conversations we always have, we have to create the right container that can hold that level of depth. In this case, the container is the circle, where we pass a talking piece and listen deeply to each person’s stories without interrupting or redirecting the conversation.

Recently, a few people have asked whether the principles that I teach (that emerge out of The Circle Way and The Art of Hosting) might be transferable to other, less formal conversations. What if I have to have a difficult conversation with my parents or siblings, for example? Or with my co-workers? Or my kids? What can I do to make sure everyone is heard in an environment where I’m certain they’d all laugh at the idea of a talking piece?

In many of our day-to-day conversations, it may not be practical or even desirable to set the chairs in a circle or bring in a facilitator to help you navigate difficult terrain. But that doesn’t mean you can’t be intentional about creating the right container for your conversations.

Here are some tips for creating containers for meaningful everyday conversations:

1. Consider the way the physical environment fits the conversation. If you want to have a potentially contentious conversation with your staff, for example, you might find that a meeting space away from your office provides a more neutral environment. If you want to talk to a friend about something that will invite vulnerability and deep emotion, you might not want to do it in a coffee shop where you run the risk of overexposure. Or if you need to talk to your parents about their declining health, it’s probably best to do that in an environment that feels safe for them.

2. Find ways to make the physical environment more conducive for intimate and intentional conversation. If you wish to invoke the essence of circle, for example, you could place a candle on the table between you. Or move the table out of the way entirely to remove the boundaries. If you want to invite creative thinking into the room, set out blank paper and coloured markers for doodling. (This would be a great way of planning your vacation with your family, for example.) Consider how the space can help you create conditions for success. Even if you are meeting online, you can still evoke safe physical space by inviting participants to imagine the common elements they would place in a room if they were all together.

3. Host yourself first. If you know that a conversation will be difficult for you and/or anyone else involved, be intentional about preparing for it well. Take some time for self-care and personal reflection. Go for a walk, write in your journal, meditate, or have a hot bath. You’ll be much more prepared to bring your best to a conversation if you enter it feeling relaxed and strong. If you plan to ask some hard questions in the conversation that might trigger others in the room, ask yourself those questions first and write whatever comes up for you in your journal. Don’t ask of anyone else what you’re not prepared to first ask of yourself.

4. Ask generative questions. Questions have the power to shut down the conversation if they come across as judgmental or closed-minded, or they have the power to help people dive more deeply into their stories and imagine a new reality together. Consider how your questions make the people you’re in conversation with feel heard and respected, and consider how a question might invite everyone present to generate fresh perspectives and deeper relationships.

5. Model vulnerability and authenticity. In order to engage in deep and meaningful relationships, participants need to be willing to be vulnerable and authentic. If you want to invite others into that space of openness and vulnerability, you need to be prepared to go there yourself. Consider starting the conversation with a personal story that will invite similar storytelling from others. Storytelling opens hearts and brings down defenses, and that’s the place where meaningful conversation thrives.

6. Listen well. People are much more inclined to engage when they feel that they are seen and heard and not judged or marginalized. Practice deep listening. As Otto Scharmer and Katrin Kaufer teach in Leading from the Emerging Future, we need to move beyond level 1 (downloading) and level 2 (factual) listening to level 3 (empathic) and level 4 (generative) listening. Empathic listening is about being willing to enter into someone else’s story and be impacted and changed by it. Generative listening is about being fully present in your listening in a way that can generate something new and fresh out of that shared space. If you model effective listening, it will be much easier for others to follow your example. Even if you don’t use a talking piece, imagine that the person you’re listening to is holding a talking piece and give them undivided attention. When they are fully heard, they will be more likely to do the same for you.

7. Guard the space and time carefully. When we gather in The Circle Way, one person serves as the guardian, paying attention to the energy of the room and bringing the conversation back to intention when it wanders off. This person takes responsibility for ensuring that the space is protected, not allowing interruptions or distractions. When you are in a conversation that is important to you, consider how you can guard the space. Eliminate distractions like cell phones or other electronics. Consider what needs attention in order to make everyone feel safe and protected. When vulnerability is called for, for example, take care to create an environment where nobody is allowed to interrupt the storytelling.

8. Co-create future possibilities. If you enter a conversation convinced that you know how it’s supposed to turn out, you will limit what can happen in that conversation. Those you’ve invited into the conversation will sense that their participation is not fully valued and will shut down and not offer their best. Instead, enter a conversation with an open heart, an open mind, and an open will and be prepared to emerge with a new possibility you’ve never considered before. Allow the stories and ideas generated in the conversation to change the future and to change you.

When you begin to pay more attention to the container in which you hold your conversations, you’ll be surprised at how much more depth and meaning will emerge. Sometimes, this will mean difficult things will surface and it won’t always be comfortable, but with the right care and attention, even the difficult things will help you move in a positive direction.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Feb 18, 2015 | circle, Community, Leadership, Uncategorized

“The moment we commit ourselves to going on this journey, we start to encounter our three principal enemies: the voice of doubt and judgment (shutting down the open mind), the voice of cynicism (shutting down the open heart), and the voice of fear (shutting down the open will).” – Otto Sharmer

Lessons in colonialism and cultural relations

Recently I had the opportunity to facilitate a retreat for the staff and board members of a local non-profit. At the retreat, we played a game called Barnga, an inter-cultural learning game that gives people the opportunity to experience a little of what it feels like to be a “stranger in a strange land”.

To play Barnga, people sit at tables of four. Each table is given a simple set of rules and a deck of cards. After reading the rules, they begin to play a couple of practice rounds. Once they’re comfortable with the rules of play, they are instructed to play the rest of the game in silence.

After 15 or 20 minutes of playing in silence, the person who won the most tricks at each table is invited to move to another table. The person who won the least tricks moves to the table in the opposite direction. All of the rules sheets are removed from the tables.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

Newcomers (ie. immigrants) have now arrived in a place where they expect the rules to be the same, find out after making a few mistakes that they are in fact different, and have no shared language to figure out what they’re doing wrong. Around the room you can see the confusion and frustration begin to grow as people try to adapt to the new rules, and those at the table try to use hand gestures and other creative means to let them know what they’re doing wrong.

After another 15 or 20 minutes, the winners and losers move to new tables and the game begins again. This time, people are less surprised to find out there are different rules and more prepared to adapt and/or help newcomers adapt.

After playing for about 45 minutes, we gathered in a sharing circle to debrief about how the experience had been for people. Some shared how, even though they stayed at the table where the rules hadn’t changed, they began to doubt themselves when others insisted on playing with different rules. Some even chose to give up their own rules entirely, even though they hadn’t moved.

In the group of 20 people, there was one white male and 19 women of mixed races. What was revealing for all of us was what that male was brave enough to admit.

“I just realized what I’ve done,” he said. “I was so confident that I knew the rules of the game and that others didn’t that I took my own rules with me wherever I went and I enforced them regardless of how other people were playing.”

It should be stated that this man is a stay-at-home dad who volunteers his time on the board of a family resource centre. He is by no means the stereotypical, aggressive white male you might assume him to be. He is gracious and kind-hearted, and I applaud him for recognizing what he’d done.

What is equally interesting is that all of the women at the tables he moved to allowed him to enforce his set of rules. Whether they doubted themselves enough to not trust their own memory of the rules, or were peacekeepers who decided it was easier to adapt to someone else who felt stronger about the “right” way to do things, each of them acquiesced.

Without any ill intent on his part, this man inadvertently became the colonizer at each table he moved to. And without recognizing they were doing so, the women at those tables inadvertently allowed themselves to be colonized.

If we had played the game much longer, there may have been a growing realization among the women what was happening, and there might have even been a revolt. On the other hand, he might have simply been allowed to maintain his privilege and move around the room without being challenged.

Making the learning personal

Since that game at last week’s retreat, the universe has found multiple opportunities to reinforce this learning for me. I have been reminded more than once that, despite my best efforts not to do so, I, too, sometimes carry my rules with me and expect others to adapt.

Yesterday, these lessons came from multiple directions. In one case, I was challenged to consider the language I used in the blog post I shared yesterday. In writing about the race relations conversation I helped Rosanna Deerchild to host on Monday night, I mentioned that “we all felt like we’d been punched in the gut” when our city was labeled the “most racist in Canada”. Several people pointed out (and not all kindly) that I was making an assumption that my response to the article was an accurate depiction of how everyone felt. By doing so, I was carrying my rules with me and overlooking the feelings of the very people the article was about.

Not everyone felt like they’d been punched in the gut. Instead, many felt a sense of relief that these stories were finally coming out.

In the critique of my blog post, one person said that my comment about feeling punched in the gut made her feel punched in the gut. Another reflected that mine was a “settler’s narrative”. A third said that I was using “the same sensationalist BS as the Macleans article”.

I was mortified. In my best efforts to enter this conversation with humility and grace, I had inadvertently done the opposite of what I’d intended. Like the man in the Barnga game, I assumed that everyone was playing by the same set of rules.

I quickly edited my blog post to reflect the challenges I’d received, but the problem intensified when I realized that the Macleans journalist who wrote the original article (and who’d flown in for Monday’s gathering) was going to use that exact quote in a follow-up piece in this week’s magazine. Now not only was I opening myself to scrutiny on my blog, I could expect even harsher critique on a national scope.

I quickly sent her a note asking that she adjust the quote. She was on a flight home and by the time she landed, the article was on its way to print. I felt suddenly panicky and deeply ashamed. Fortunately, she was gracious enough to jump into action and she managed to get her editor to adjust the copy before it went to print.

Surviving a shame shitstorm

Last night, I went to bed feeling discouraged and defeated. On top of this challenge, I’d also received another fairly lengthy email about how I’ve let some people down in an entirely different circle, and I was feeling like all of my efforts were resulting in failure.

At 2 a.m., I woke in the middle of what Brene Brown calls a “shame shitstorm”. My mind was reeling with all of my failures. Despite my best efforts to create spaces for safe and authentic conversation, I was inadvertently stepping on toes and enforcing my own rules of engagement.

As one does in the middle of the night, I started second-guessing everything, especially what I’d done at the gathering on Monday night. Was I too bossy when I hosted the gathering? Did I claim space that wasn’t mine to claim? Were my efforts to help really micro-aggressions toward the very people I was trying to build bridges with? Should I just shut up and step out of the conversation?

By 3 a.m., I was ready to yank my blog post off the internet, step away into the shadows, and never again enter into these difficult conversations.

By 4 a.m., I’d managed to talk myself down off the ledge, opened myself to what I needed to learn from these challenges, and was ready to “step back into the arena”.

Some time after 4, I managed to fall back to sleep.

Moving on from here

This morning, in the light of a new day, I recognize this for what it is – an invitation for me to address my own shadow and deepen my own learning of how I carry my own rules with me.

If I am not willing to address the colonizer in me, how can I expect to host spaces where I invite others to do so?

Nobody said this would be easy. There will be more sleepless nights, more shame shitstorms, and more days when my best efforts are met with critique and even anger.

But, as I said in the closing circle on Monday night, I’m going to continue to live with an open heart, even when I don’t know the next right thing to do, and even when I’m criticized for my best efforts.

Because if I’m not willing to change, I have no right to expect others to do so.

I was on Whidbey Island for two purposes – a.) to work with a small circle of people on a new website for

I was on Whidbey Island for two purposes – a.) to work with a small circle of people on a new website for  Throughout the week, I did the work to invite this deeper voice more fully into my life and work. I walked the labyrinth several times, I spent a day in silence, I had deep and personal conversations with like-minded people, I wandered the woods, I sat in circle and listened to other people’s stories, and I wrote pages and pages in my journal. I also shed a lot of tears and let some of my fears hold court until they felt adequately heard and were willing to let me move on.

Throughout the week, I did the work to invite this deeper voice more fully into my life and work. I walked the labyrinth several times, I spent a day in silence, I had deep and personal conversations with like-minded people, I wandered the woods, I sat in circle and listened to other people’s stories, and I wrote pages and pages in my journal. I also shed a lot of tears and let some of my fears hold court until they felt adequately heard and were willing to let me move on.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.