by Heather Plett | May 1, 2015 | Community, growth, journey, Uncategorized

“If we can share our story with someone who responds with empathy and understanding, shame can’t survive.” – Brené Brown

I like fruity tea. Passionate peach, blueberry bliss, raspberry riot – you name it, I probably like it. But at some point in my life, I picked up the idea that fruit teas aren’t for REAL tea drinkers. In the hierarchy of teas, I imagined them stuck at the bottom, the uncoolest of the hot beverages.

I have no idea where I picked up on that tea story. Perhaps someone made fun of me for my tea choice. Perhaps it was just a vibe I picked up. Perhaps I made it up myself. However I picked it up, I let it affect my tea choices. For years, I was afraid to drink fruity tea in public, afraid that the real tea drinkers might notice and judge me for it.

Silly, isn’t it? But isn’t that how most of our shame stories are – rather foolish, once brought into the light of day?

To be honest, some of my shame stories around food choices are rooted in being raised poor, on a farm, and as part of a small Mennonite subculture that kept itself somewhat apart by not engaging in all of the activities (ie. Fall suppers where I might have been exposed to other kinds of tea) in our community. We didn’t have access to “fancy” foods, and so, when I became an adult and was faced with choices that I wasn’t used to, I was afraid I would choose the wrong thing and people would discover how uncultured I was. I was ashamed of being uncultured – ashamed of being a Mennonite farm kid who wasn’t as sophisticated as I assumed the city kids of more worldly-wise cultures were.

We pick up shame stories for a lot of different reasons. Some of them have clear origins (like parents who made us believe we were shameful) and others can only be understood after years of excavation and personal work. Some are relatively easy to release (I now drink fruity tea in public when I want to) and others have become so imbedded into our identity, they become part of our DNA (like the shame around cultural/racial identity).

We inherit many of our shame stories from the generations that came before us in our lineage. Those are the ones that become particularly imbedded into our identity.

After spending several years working in international development, and then a few years on the board of a feminist organization, and now as part of a team doing race relations conversations, I’ve noticed a pattern about cultural shame. Though shame is common to all cultures, it has a particularly strong hold among oppressed cultures.

One of the greatest weapons of oppression is shame. When oppressors manage to inflict shame on people, they increase their own power and diminish the ability of those they oppress to rise up out of their oppression. Shame diminishes courage and strength.

Ironically, though, many of the shame stories related to oppression are passed down not directly from the oppressors themselves but from those above us in our lineage who have been oppressed before us – not because they want to oppress us, but because they want to protect us.

We pass the stories of oppression down to those we most want to protect. When we inherit them as young children, though, those oppression stories become shame stories.

In the book “The Shadow King: The invisible force that holds women back“, Sidra Stone teaches that we adopt the inner patriarchy (the voice that tells women that they are not worth as much as men) from our mothers. It is primarily our mothers who teach us how to stay small, how to please the men, how to avoid getting hurt, and how to give up our own desires in deference to others in our lives (especially men). They do it to protect us, because that’s the only way they’ve learned to protect themselves. And so it goes, from generation to generation, each mother passing down to her daughters the stories of how they can stay safe.

Last week, many of us watched the video of a Baltimore mother who beat her son in public when she found him among the protestors. Desperate to protect him, she pulled him away from enemy lines and taught him, by her own raised hand, that he must learn to submit or risk being killed.

The problem is that those of us growing up in environments where we’re learning these stories from our parents do not yet have a reference point to understand generations of oppression. The only way we know how to interpret our parents’ attempts to keep us small and silent is to believe that they will stop loving us if we become too large and vocal. We become convinced that we are worthy of shame and not love. Though that mother in Baltimore may tell her son a thousand times that she did it out of love and a desperate need to protect him, I suspect there will always be a small child inside him who will believe “my mother shamed me in public, therefore I am worthy of shame.”

Remember the experiment with the monkeys, where a beautiful bunch of bananas hung above a ladder, but every time a monkey would climb to get the bananas, all of the monkeys in the cage would be sprayed with water? Not wanting to be sprayed, the monkeys kept pulling down any monkey who attempted to climb the ladder. Even after all of the monkeys were replaced (one by one) and nobody had experienced the spraying, they still kept any new monkey from climbing the ladder, because they themselves had been stopped. Those new monkeys (if they think like humans), not knowing the history, probably believed “I have done something wrong and my tribe is ashamed of me. I must not be worthy of happiness.” And then they passed the story down to the next generation, pulling down anyone who dared to climb the ladder.

Growing up with the shame inflicted by generations and generations of shamed people, we forget that it is not the lack of love they had that caused them to pass this down to us, it is their wounded love that meant they didn’t know how else to protect themselves and us from further wounding.

And, remarkably, it’s not only psychological – it becomes planted in our very DNA. Studies have shown that trauma has changed people’s DNA and that that DNA has been passed down to subsequent generations, showing up as irrational fear and the tendency to be triggered even if they didn’t directly experience that trauma. If trauma can be passed down through DNA, I’m fairly certain that shame can too, since trauma and shame are often closely linked.

How do we heal these generations of wounds? That is something that I’m just beginning to explore and read about (as are many others) and I welcome anyone’s thoughts, ideas, or experience.

I know that it must be a holistic response, involving body, mind, and spirit. In The MindBody Code, Mario Martinez talks about how we have to heal the shame in our bodies as well as our minds. He teaches contemplative embodiment practices that help replace the shame stories with honour stories.

I also believe that healing shame involves dancing, singing, art-making, spiritual practices, and lots of touch. We can’t heal shame with simply left-brain, logical thinking – we have to engage in creative, right-brain spiritual meaning-making. It helps to create rituals (ie. painting the shame monsters and then painting safe places for them to be exposed), embody our healing (ie. dancing our way into courage), and find spiritual practices that teach us to let go and trust (ie. mindfulness meditation).

And, more than anything, I believe that healing happens in community. Ironically, we pick up our shame through our relationships and we heal it through healthier relationships. That’s the nature of community – it comes with both the good and the bad, the wounding and the healing. In order to heal, we have to find safe community in which we can be vulnerable without fear. When we expose our shame stories among those who hold space for us, the shame loosens its power over us. Intentional circle practices are the best practices I know of for this kind of work.

Happily, there have also been studies that demonstrate that those changes to the DNA can be reversed, so there is hope for the generations that come after us if we do our work to heal. Shame is not the end of the story. We can heal it for ourselves and future generations.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Apr 29, 2015 | grief, growth, journey

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” – Viktor Frankl

After last week’s post about

serving as wounded healers, I received a thought-provoking email from a reader.

“I have been wondering a lot about the language surrounding letting go, moving on, and forgiving. The way the phrases come out seem misleading to me. I mean, how does one just simply choose to forgive, or let go when there is a big part that just isn’t willing to do that yet even though we want to? We can intellectually get why and how, but doing so is almost an entirely different thing.”

I have been thinking a lot about his question ever since. Even after I sent a response to his email, I kept wondering what else there might be to say. Is “letting go” a one time decision, or is it a daily commitment? Is it possible to “let go” entirely, or is it more true that we loosen our grip for awhile until something unexpectedly triggers us and returns us to that wound for another (hopefully deeper) healing journey?

In last week’s post, I made reference to the time a man climbed through my window and raped me in my bed. After years of seeking healing for that wound, I’d like to think that I’ve let go, moved on, and forgiven that man, but in truth, I am still occasionally triggered and the old wounds come back to haunt me. Last Fall, for example, when Tina Fontaine’s body was found in the river near where I’d lived at the time, and then, a few months later, Rinelle Harper survived a similar attack, I found myself triggered once again. Around the same time, it was revealed that Jian Gomeshi, a celebrity in Canada, had been sexually assaulting women for years and getting away with it. I found myself angry, shaken, and some days nearly unable to get out of bed.

Have I let go? Have I healed? Have I forgiven? Yes… and no. I have worked through much of the pain, I have grown immensely from the experience, I have learned to trust people again, and I have used the experience to help me serve as a more compassionate wounded healer. And yet… I can still get angry, I can still fear intimacy, and I can still allow some of the emotional wounds to change how I treat my own body. Last Fall’s triggering taught me that I still have more layers to heal in this story.

So… does that mean that we can never be fully functioning members of society because we are all always carrying around old wounds? No, that’s not it at all. Our wounds change us and become part of our stories, but they do not define us nor do they own us. Though healing may be a lifelong journey, we are still responsible to do the work and to offer the gifts of what we’ve learned to others.

Here are some of my thoughts on the healing journey…

1.) Life is more like a labyrinth than a linear path. A labyrinth journey takes you toward centre, but it never takes you directly there. First you wind in and out, sometimes close to centre and sometimes far away. Life is the same way. Sometimes you feel like you’ve reached your goal and that your wounds are healed, and then suddenly the path turns and you are once again wandering in a wasteland of doubt and despair. That doesn’t mean you’re doing it wrong, it simply means that you have more to learn from the place at the edge of the circle.

2.) Pain can be our greatest teacher, but we have to allow ourselves to feel it in order to learn its lessons. We can’t short-circuit the learning that grief and struggle bring to our lives. When we try to ignore it by staying busy or dull it by turning to substance abuse or avoid it by pretending we can simply return to life as usual, we simply put it on hold and can expect that it will surface again later in life in an more urgent and unhealthy way.

3.) When we are mindful, our wounds have less ability to control us. In mindfulness meditation (my limited training comes mostly from the Shambhala Buddhist tradition), we are taught not to try to stop the thoughts, but to witness them and simply let them pass. The same is true for how we should treat our anger, judgement, fear, etc. We shouldn’t try to shut it down or deny ourselves the experience of it. Instead, we have an opportunity to witness it, inquire into it (What is this moment teaching me? What do I still have to learn from this emotional experience? What is the fear hidden beneath my anger?) and then allow it to pass. (I intentionally say “allow” it to pass rather than “let it go” because allowing is less about our control and more about acceptance.) That doesn’t mean it won’t come back again, but when it does come back, it has less ability to debilitate and control us.

4.) Those who search for meaning in any situation are better able to heal from it. Is there a reason for the suffering in the world? I don’t know. It’s hard to justify the suffering caused by the earthquake in Nepal, for example. There may not be a cosmic reason for it, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t meaning for each of us as we live through the suffering. As Viktor Frankl reminds us, in Man’s Search for Meaning, those people who were best able to survive the atrocities of the concentration camps during the Second World War were those people who found meaning in their suffering. “Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

5.) As wounded healers, we can offer healing even if we’re still on the healing journey ourselves. Although it’s important to work on our own wounds first (so that we don’t use those wounds as an excuse to inflict more wounds on others), we can’t wait until we are “completely healed” to serve the world around us. There is no such thing as “completely healed”. Instead, there are those who are further along the healing journey than others who reach back and offer compassion and guidance to those behind them. When I started teaching, I adopted as my mantra George Bernard Shaw’s quote… “I’m not a teacher: only a fellow traveler of whom you asked the way. I pointed ahead – ahead of myself as well as you.” Change the word “teacher” to “healer” and it still applies.

6.) Our wounds make us beautiful. Mark Nepo shares the story of a brokenhearted young woman who finds an old man in the woods. When she shares her story of heartbreak with the man, he tells her the story of how each of us is like a flute and each time we are wounded, a new hole is carved into us. ‘It is a simple fact that a flute can make no music…if it has no holes,” says the wise old man. “Each being on earth is such a flute, and each of us releases our songs when our Spirit passes through the holes carved by our life experiences.’” No two flutes have the same holes and therefore no two flutes make the same music.

If you’ve been wounded and are on the path to healing, remember that you are beautiful, right now, exactly as you are. This healing journey will bring you many gifts that are needed for the healing of this world. Be mindful, search for meaning, and let yourself be changed.

Note: I’d like to dedicate one post a month to wrestling with readers’ questions, so if you have been contemplating something that you’d like me to talk about, simply add a comment with your question. I don’t promise “answers” or “solutions”, I’ll simply offer my thoughts from my place on the journey.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Apr 22, 2015 | Compassion, growth, journey

“In a futile attempt to erase our past, we deprive the community of our healing gift. If we conceal our wounds out of fear and shame, our inner darkness can neither be illuminated nor become a light for others.” – Brennan Manning

On Sunday I sat in a circle of wounded healers. These were the openhearted people who had gathered for our second

Race to Peace conversation.

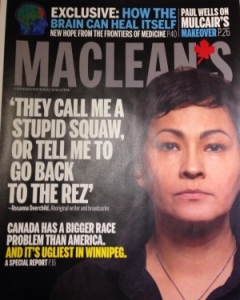

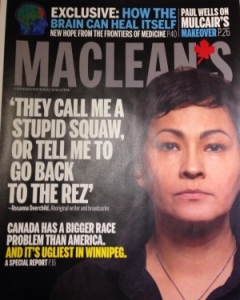

It started with Rosanna Deerchild, the first to offer healing out of her own wounds. In the Maclean’s article that named our city the most racist in Canada, Rosanna shared how she has faced racism on a weekly basis. “Someone honks at me, or yells out ‘How much’ from a car window, or calls me a stupid squaw, or tells me to go back to the rez. Every time, it still feels like getting punched in the face.”

When Rosanna’s face appeared, without her blessing, on the front cover of Maclean’s, and she was suddenly thrust into the spotlight as the “face of racism”, she made a courageous choice. Instead of responding with outrage, she decided to reach out with healing. She offered to host dinner and a conversation with people in the city about race relations, and out of that willingness, Race to Peace was born.

Rosanna’s choice inspired others to make similar choices. In the circle that gathered on Sunday, there were many who had been wounded and are now willing to extend healing.

There was the man who’d gotten a girl pregnant at 13, joined a gang, landed in jail, and was now studying to be a social worker so that he could help other young men stay out of gangs and jail and make a positive impact on the world.

There was the woman who’d immigrated from the Philippines and had experienced racism in trying to find a job in Canada and wanted to support other job-seekers with similar stories.

There was the man who’d experienced conflict in El Salvador who is now passionate about peace in his adopted country.

There was my husband, who dropped out of school in junior high because of his own anxiety and insecurity, found the courage to go to university as a 40 year old father, and now teaches in a jail.

And there was me… once raped by an indigenous man and determined not to let that make me bitter toward people of his race or gender.

The term “wounded healer” comes out of the work of psychologist Carl Jung, who believed that analysts are compelled to treat patients because the analysts themselves are wounded. My friend Jo, who is also a psychologist, says that most of the people she studied with ended up in psychology for that very reason. According to some research by Alison Barr, “73.9% of counselors and psychotherapists have experienced one or more wounding experiences leading to their career choice.”

This is not unique to psychologists. Caregivers of all kinds (nurses, hospice workers, coaches, social workers, grief counselors, etc.) are often in the line of work they’re in because they first experienced their own wounds. (Of note: Henri Nouwen has written a book related to the topic, called Wounded Healer.)

“As soon as healing takes place, go out and heal somebody else.” – Maya Angelou

We are always given a choice what to do with our wounds. We can use them as an excuse to go out and wound other people (which is at the root of most of the pain in the world), or we can do the hard work of healing and then use that healing as a gift to help in other’s healing. The wounded healer emerges in all of us who make the right choice.

I first stepped into my coaching vocation in a hospital room.

I’d landed there in the middle of my third pregnancy after my cervix had suddenly become incompetent and medical intervention had failed to correct the situation. Truth be told, I wouldn’t have been in that situation if it hadn’t been for a series of doctors’ errors.

Lying on my back in a hospital room, fearing for my son’s life, I realized I had a choice to make. I could be bitter and resentful and blame the doctors for what had happened, or I could accept the situation and forgive the doctors. I chose the second.

Once I made that choice, I was at peace. Though it was stressful not knowing what would happen to the baby and not being in control of my own life while I waited, I was surprisingly calm. Since I could do nothing else, I began to turn my hospital room into a little spiritual retreat centre, with gentle music playing, cards and pictures from my kids on the wall, and fresh fruit and flowers on the windowsill.

People began to notice how peaceful my room was, and unexpected visitors started showing up. Other patients, cleaning staff, doctors, friends, and even other people’s visitors – all of them showed up there at one time or another and all remarked at the peacefulness of the room. Some of the nurses on the floor started dropping in during their breaks because my room was more relaxing than their coffee room. A cancer patient from across the hall became a regular visitor because her visits made her feel less anxious.

While they were there, people began to share things with me – personal things that they were working through in their own lives. There was the nurse who was struggling with parenting decisions, another nurse who’d moved from Africa and was finding it difficult to adjust to a new culture, the cancer patient who was afraid to die, and a friend who was trying to make a difficult decision about whether to step into leadership.

Without intending to, I became confidante and coach to those people. Long before I knew the term “holding space” I was doing it in that hospital room for anyone who needed it. I had plenty of time on my hands and I was willing to be of service and that willingness drew people to me. It was both humbling and eye-opening.

There I was, confined to my hospital room, serving as a wounded healer to friends and strangers alike. Because of my own fear, I could hold theirs without judgement. Because I’d walked through injustice and anger and came through to forgiveness, they saw something in me that they could trust. Because I made the effort to create a peaceful space in a tumultuous situation and environment, they sought me out as friend and healer.

That experience changed my life and led me to the work that I now do. None of it could have happened, though, if I hadn’t first been wounded. If that pregnancy had been easy and had resulted in a living child (instead of my stillborn son, Matthew), I might have carried on in my relatively successful corporate job. I might never have discovered my ability to hold space for other people and might never have contributed to the healing of their wounds.

The same can be said for that long ago rape. If I hadn’t been changed by that circumstance, healed the wound the rapist left me with, and come through determined not to perpetuate a cycle of oppression and wounding, I might never have stepped forward when Rosanna spoke of her desire to hold conversations about race relations.

Each of us has a choice – stay wounded and let the wounds fester, or seek healing and offer that healing to others.

by Heather Plett | Apr 1, 2015 | beginnings, grief, growth

“Treating ourselves like appliances that can be unplugged and plugged in again at will or cars that stop and start with the twist of a key, we have forgotten the importance of fallow time and winter and rests in music. We have abandoned a whole system of dealing with the neutral zone through ritual, and we have tried to deal with personal change as though it were a matter of some kind of readjustment.” – William Bridges

One of the women in my women’s circle shared recently that she has a hard time explaining to her husband where she goes every Thursday. “He just doesn’t get it,” she said. “He keeps asking ‘But… what do you do there? What’s the purpose?’ He can’t understand why we’d want to sit in a circle and share stories of our lives when we’re not accomplishing anything or learning anything.”

This is a common story in my work. “But what will we do?” people ask when I talk about my retreats, workshops, or even coaching sessions. I talk about making mandalas, walking labyrinths, and sitting in conversation circles, but that’s often not enough for people who believe life is only valuable when we’re doing/accomplishing/fixing/building/growing/learning something.

We have created a culture in which busy = important, accomplishment = valuable, and idleness = wasting time. Even when we go away for retreat or sit in circle, we think we have to be able to name what we accomplished in our time away. If we don’t have a checklist of “things we got done” then the time wasn’t valuably invested. To say we simply wandered in the woods for a few days is the equivalent of admitting we’re lazy and unproductive and that we can’t be trusted to contribute to society.

We fear laziness, we chafe at lack of productivity, and we hide in shame when we take too long to “get over things”.

We have become a society that has lost the capacity for spaciousness in our transitions.

Take grief, for example. We think if we can name the “five stages of grief”, then we’ll be able to clean up the process, hide the messiness, and get through it faster.

Birth is the same. In many cultures, a mother is expected to return to “productive” work only weeks after the biggest life-changing event she’s ever gone through.

And those are the “big” ones. When it comes to “smaller” transitions (changing careers, ending relationships, having a car accident, etc.), we’re hardly even given permission to talk about them, let alone experience the full weight of them in our lives. There are more important things to do than to sit around in sharing circles talking about the hard things life has thrown our way.

In one of the best books I’ve read on the subject, Transitions, William Bridges calls the space between the ending of one phase of our lives and the beginning of another “the neutral zone”. Some time around the industrial revolution, we lost touch with the neutral zone.

“In other times and places the person in transition left the village and went out into an unfamiliar stretch of forest or desert. There the person would remain for a time, removed from the old connections, bereft of the old identities, and stripped of the old reality. This was a time ‘between dreams’ in which the old chaos from the beginnings welled up and obliterated all forms. It was a place without a name – an empty space in the world and the lifetime within which a new sense of self could gestate.”

Again and again in my coaching work, I find myself in conversation with people who fear the neutral zone. When we begin the conversation, they talk about some big change they feel they need to make in their lives and they express frustration about their lack of ability to get there quickly and easily. “What’s wrong with me?” they almost always say. “I know that it’s time for change, but I can’t seem to find clarity or drive to get me to the next stage of my life. I feel like I’m stuck in quicksand.” Again and again they beat themselves up for not living up to some arbitrary expectation they’ve placed on themselves or they feel others are placing on them.

Somewhere in the middle of the first conversation, I nudge them to give themselves permission to “just be lost” for awhile. Usually, there s some resistance to this. Lostness is not something they’ve ever been taught to value. Lostness = unworthiness.

By the second or third conversation, most have spoken aloud their desire for more spaciousness. “I just feel like making art for awhile” or “I just need to learn to give myself permission to feel this grief deeply” or “I’m going to take a few months just to ‘be’ and not ‘do’.”

It’s remarkably hard to get to that place of spaciousness and acceptance. Sometimes it’s even hard for me, as a coach, to invite them into that place. The voices in my head often remind me “They’re paying you good money for this – shouldn’t you help them accomplish something? Shouldn’t you do something more valuable than give them permission to just be for awhile?”

That moment of doubt always passes though, when I remember how crucial it is for us to transition well and to honour the neutral zone before we step into the new beginning. If I give my clients nothing else but the permission to honour their own timing in their transitions, then I have done well.

What we don’t realize, when we rush through the neutral zone, is that we’re short-circuiting real growth. If we deny ourselves of the fallow time, the winter season when seeds lie dormant underground, then our growth will be stunted and unhealthy, and, more often than not, the emotions we denied ourselves will emerge in less healthy ways later in our lives.

We need the neutral zone and we need to honour and give space for it in others as well.

A bamboo plant spends three or four years growing a good root system before anything emerges above the ground. In the same way, we need to invest in our rootedness before the growth will be obvious to anyone else. We need to create the space and time to “just be” before we are ready to “do”.

Learn to create spaciousness in your life by giving yourself permission to wander in the woods, to make messy art, to stare into space, to sit in long conversations with friends, to feel emotions deeply, to savour good food, to say no to some of your commitments, or to go on a pilgrimage or vision quest.

This is not time “wasted”, it’s time well invested in your own growth and well-being.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Jan 28, 2015 | art of hosting, change, growth, journey, Leadership

“The success of our actions as change-makers does not depend on what we do or how we do it, but on the inner place from which we operate.” – Otto Sharmer

Last week, the city that I love and call home was named “the most racist city in Canada.” That hurt. It felt like someone had insulted my family.

Last week, the city that I love and call home was named “the most racist city in Canada.” That hurt. It felt like someone had insulted my family.

The article mentions many heartbreaking stories of the way that Indigenous people have been treated in our city, and while I wanted to say “but… we’re so NICE here! Really! You have to see the other side too!” I knew that there was undeniable truth I had to face and own. My family isn’t always nice. Neither is my city.

Though I work hard not to be racist, have many Indigenous friends in my circles, and am married to a Metis man, I knew that my response to the article needed to not only be a closer look at my city but a closer look at myself. I may not be overtly racist, but are there ways that I have been complicit in allowing this disease to grow around me? Are there things that I have left unsaid that have given people permission for their racism? Are there ways in which my white privilege has made me blind?

Ever since the summer, when I attended the vigil for Tina Fontaine, a young Indigenous woman whose body was found in the river, I have been feeling some restlessness around this issue. I knew that I was being nudged into some work that would help in the healing of my city and my country, but I didn’t know what that work was. I started by carrying my sadness over the murdered and missing Indigenous women into the Black Hills when I invited women on a lament journey.

Ever since the summer, when I attended the vigil for Tina Fontaine, a young Indigenous woman whose body was found in the river, I have been feeling some restlessness around this issue. I knew that I was being nudged into some work that would help in the healing of my city and my country, but I didn’t know what that work was. I started by carrying my sadness over the murdered and missing Indigenous women into the Black Hills when I invited women on a lament journey.

This week, after the Macleans article came out, our mayor made a courageous choice in how he responded to the article. In a press conference called shortly after the article spread across the internet, he didn’t get defensive, but instead he spoke with vulnerability about his own identity as a Metis man and about how his desire is for his children to be proud of both of the heritages they carry – their mother’s and his. He then invited several Indigenous leaders to speak.

There was something about the mayor’s address that galvanized me into action. I knew it was time for me to step forward and offer what I can. I sent an email and tweet to the mayor, thanking him for what he’d done and then offering my expertise in hosting meaningful conversations. Because I believe that we need to start healing this divide in our city and healing will begin when we sit and look into each others’ eyes and listen deeply to each others’ stories.

After that, I purchased the url letstalkaboutracism.com. I haven’t done anything with it yet, but I know that one of the things I need to do is to invite more people into a conversation around racism and how it wounds us all. I have no idea how to fix this, but I know how to hold space for difficult conversations, so that is what I intend to do. Circles have the capacity to hold deep healing work, and I will find a way to offer them where I can.

Since then, I have had moments of clarity about what needs to be done next, but far more moments of doubt and fear. At present, I am sitting with both the clarity and the doubt, trying to hold both and trying to be present for what wants to be born.

Here are some of the things that are showing up in my internal dialogue:

- Isn’t it a little arrogant to think I have any expertise to offer in this area? There are so many more qualified people than me.

- What if I offend the Indigenous people by offering my ideas, and become like the colonizers who think they have the answers and refuse to listen to the wisdom of the people they’re trying to help?

- There are already many people doing healing work on this issue, and many of them are already holding Indigenous circles. I have nothing unique to contribute.

- What if I host sharing circles and too much trauma and/or conflict shows up in the circle and I don’t know how to hold it?

- What if this is just my ego trying to do something “important” and get attention for me rather than the cause?

And so the conversation in my head goes back and forth. And the conversations outside of my head (with other people) aren’t much different.

At the same time as this has been going on, I have been working through the first two weeks of course material for U Lab: Transforming Business, Society and Self. In one of the course videos, Otto Sharmer talks about the four levels of listening – from downloading (where we listen to confirm habitual judgements), to factual (listening by paying attention to facts and to novel or disconfirming data), to empathic (where we listen with our hearts and not just our minds), and finally to generative (where we move with the person speaking into communion and transformaton).

As soon as I read that, I knew that whatever I do to help create space for healing in my city, it has to start with a place of deep listening – generative listening, where all those in the circle can move into communion and transformation. I also knew, as I sat with that idea, that that generative listening has to begin with me.

If I am to serve in this role, I need to be prepared to move out of my comfort zone, into generative listening with people who have been wounded by racism in our city AND with people who live with racial blindspots. AND (in the words of Otto Sharmer) I need to move out of an ego-system mentality (where I am seeking my own interest first), into a generative, eco-system mentality (where I am seeking the best interest of the community and world around me).

So that is my intention, starting this week. I already have a meeting planned with an Indigenous friend who has contributed to, and wants to teach, an adult curriculum on racism, to find out how I can support her in this work. And I will be meeting with another friend, a talented Indigenous musician, about possible partnership opportunities. And I will be a sitting in an Indigenous sharing circle, listening deeply to their stories.

I am not sharing these stories to say “look at me and all of the good things I’m doing”. That would be my ego talking, and that’s one of the things I’m trying to avoid. Instead, I’m sharing it to say “look at the complexity that a thinking woman (sometimes over-thinking woman) goes through in order to become an effective, and humble, change-maker.

That brings me back to the quote at the top of the page.

“The success of our actions as change-makers does not depend on what we do or how we do it, but on the inner place from which we operate.” – Otto Sharmer

The inner place. That is what will determine the success of our actions. I can have all the smart ideas in the world, and a big network of people to help roll them out, but if I have not done the internal work first, my success will be limited.

If I don’t do the inner work first, then my ego will run rampant and I will stomp all over the people that I say I care about. Or I will suffer from jealousy, or self doubt, or self-centredness, or vindictiveness, or all of the above.

If I don’t do the internal work and ask myself important questions about what is rooted in my ego and what is generative, then I could potentially do more harm than good.

So how do I do that internal work? Here are some of the things that I do:

1. As we say in Art of Hosting work, I host myself first. In other words, I ask of myself whatever I would ask of others I might invite into circle, I look for both my shadows and my strengths, and I do the kind of self-care I would encourage my clients to do when they find themselves in the middle of big shifts.

2. I ask myself a few pointed questions to determine whether the ego is too involved. For example, when my friend came to me to share the work she wants to do, hosting circles in the curriculum she has developed, there was a little ego-voice that spoke up and said “But wait! This was supposed to be YOUR work! If you support her, you’ll have to be in the background.” The moment I heard that voice, I had to ask myself “do you truly want to make a difference around the issue of racism or do you just want to make a name for yourself?” And: “If this is successful in impacting change, but you have only a secondary role, is it still worthwhile?” It didn’t take long for me to know that I wanted to be wholeheartedly behind her work.

3. I pause. As we learn in Theory U, the pause is the most important part – it’s where the really juicy stuff happens. The pause is where we notice patterns that we were too busy to notice before. It’s where the voice of wisdom speaks through the noise. It’s where we are more able to sink into generative listening. In Theory U, we call it “presencing” – a combination of “presence” and “sensing”. There’s a quality of mindfulness in the pause that helps me notice and experience more and be awake to receive more wisdom.

4. I do the practices that help bring me to wise thought and wise action. For me, it’s journaling, art, mandala-making, nature walks, and labyrinth walks. I never make a major decision without spending intentional time in one of those practices. Almost always, something more profound and wise shows up that I wouldn’t have considered earlier.

5. I listen. The ego doesn’t want me to seek input from other people. The ego wants to be in control and not invite partners in to share the spotlight. If I want to move out of ego-system, though, I need to spend time listening for others’ stories and wisdom. This doesn’t mean I listen to EVERYONE. Instead, I use my discretion about who are the right people to seek wise council from. I listen to those who have done their own personal work, whose own egos won’t try to trap me and keep me from succeeding, and who genuinely care about the issue I’m working on.

6. I check in with myself and then move into action when I’m ready. Although the pause, the questions, and the personal practice are all very important, the movement into action is equally important. There have been far too many times when my questions and ego have trapped me in a spiral and I’ve failed to move into action. Just thinking about it won’t impact change. I need to be prepared to act, even if I still have doubt. If I fail in that action, I can always go back and re-enter the presencing stage.

This is an ongoing story and I hope to continue sharing it as it emerges. If you, too, want to become a change-maker, then I’d love to hear from you. What are the processes you go through in order to ensure your “inner place” is healthy and your listening and actions are generative? What issues are currently calling you into action?

If this resonates with you, check out The Spiral Path, which begins February 1st. Based on the three stages of the labyrinth, (release, receive, and return), it invites you to go inward to do this internal work and then to move outward to serve in the way that you are called.

Also… we’re looking for a few more change-makers to attend Engage, a one-of-a-kind retreat that will teach you more about how to do your inner work so that you can move into generative action.

by Heather Plett | Jan 13, 2015 | Community, growth, journey, Leadership

There are many reasons to be silent.

Violence (or the threat of violence) is one reason for silence. When cartoonists are murdered for satire and young school girls are kidnapped or murdered for daring to go to school, the risk of speaking up becomes too great for many people.

Sometimes the violence backfires and the voices become stronger – as in the case of Charlie Hebdo, now publishing three million copies when their normal print run was 60,000. Why? Because those with power and influence stepped in to show support for those whose voices were temporarily silenced. If the world had ignored that violence and millions of people – including many world leaders – hadn’t marched in the streets, would there have been the same outcome? If these twelve dead worked for a small publication in Somalia or Myanmar would we have paid as much attention? I doubt it.

Far too many times (especially when the world mostly ignores their plight, as in Nigeria) violence succeeds and fewer people speak up, fewer people are educated, and the perpetrators of the violence have control.

Violence has long been a tool for the silencing of the dissenting voice. Slaves were tortured or murdered for daring to speak up against their owners. Women were burned at the stake for daring to challenge the dominant culture. Even my own ancestors – the Mennonites – were tortured and murdered for their faith and pacifism.

Most likely every single one of us could look back through our lineage and find at least one period in time when our ancestors were subjected to violence. Some of us still live with that reality day to day.

There is no question that the fear of violence is a powerful force for keeping people silent. It still happens in families where there is abuse and in countries where they flog bloggers for speaking out.

Few of the people who read this article will be subjected to flogging or torture for what we say or write online, and yet… there are many of us who remain silent even when we feel strongly that we should speak out.

Why? Why do we remain silent when we see injustice in our workplaces? Why do we turn the other way when we see someone being bullied? Why do we hesitate to speak when we know there’s a better way to do things?

Because we have a memory of violence in our bones. The more I learn about trauma the more I realize that it affects us in much more subtle and insidious ways than we understand. Some of us have experienced trauma and are easily triggered, but even if we never experienced trauma in our own lifetimes, it can be passed down to us through our DNA. Your ancestors’ trauma may still be causing fear in your own life. Witnessing the trauma of other people subjected to violence may be triggering ancient fear in all of us, causing us to remain silent.

Because we have a memory of violence in our bones. The more I learn about trauma the more I realize that it affects us in much more subtle and insidious ways than we understand. Some of us have experienced trauma and are easily triggered, but even if we never experienced trauma in our own lifetimes, it can be passed down to us through our DNA. Your ancestors’ trauma may still be causing fear in your own life. Witnessing the trauma of other people subjected to violence may be triggering ancient fear in all of us, causing us to remain silent.- Because our brains don’t understand fear. The most ancient part of our brains – the “reptilian brain”, which hasn’t evolved since we were living in caves and discovering fire – is adapted for fight or flight. That part of our brain sees all threats as predators, and so it triggers our instinct to survive. Our lives are much different from our ancestors, and yet there’s a part of our brains that still seeks to protect us from woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed tigers. When our fear of being rejected by a family member for speaking out feels the same as the fear of a sabre-toothed tiger, our reaction is often much stronger than it needs to be.

- Because those who want to keep us silent have learned more subtle ways to do so. In most of the countries where we live, it is no longer acceptable to flog bloggers, but that doesn’t mean we’re not being silenced. Women have been silenced, for example, by being taught that their ideas are silly and irrelevant. Marginalized people have been silenced by being given less access to education. Those with unconventional ideas have been “gaslighted” – gradually convinced that they are crazy for what they believe.

- Because we have created an “every man for himself” culture where those who speak out are often not supported for their courage. We’re all trying to thrive in this competitive environment, and so we feel threatened by other people’s success or courage. When I asked on Facebook what keeps people silent, one of the responses (from a blogger) was about the kinds of haters that show up even in what should be supportive environments. In motherhood forums, for example, people get so caught in internal battles (like whether it is better to be a working-away-from-home parent or a stay-at-home parent) that they forget that they would be much stronger in advocating for positive change in the world if they found a way to work together and support each other. It is much more difficult to speak out when we know we’ll be standing alone.

- Because we don’t understand power and privilege. Those who have access to both power and privilege are often surprised when others remain silent. “Why wouldn’t they just speak up?” they say, as though that were the simplest thing in the world to do. It may be a simple thing, if you have never been oppressed or silenced, but if you’ve been taught that your voice has no value because you are “a woman, an Indian, a person of colour, a lesbian, a Muslim, etc.”, then the courage it takes to speak is exponentially greater. Years and years of conditioning that convinces a person of their inherent lack of value cannot be easily undone.

Several years ago, I visited a village in the poorest part of India. Though I’d traveled in several poor regions in Bangladesh, India, and a few African countries before that, this was the most depressing place I’d ever visited. This was a makeshift village populated by the Musahar people who lived at the edges of fields where they sometimes were hired by the landowners as day labourers but otherwise had to scrounge for their food (sometimes stealing grain from rats – which was why they’d come to be known as “rat eaters”).

Several years ago, I visited a village in the poorest part of India. Though I’d traveled in several poor regions in Bangladesh, India, and a few African countries before that, this was the most depressing place I’d ever visited. This was a makeshift village populated by the Musahar people who lived at the edges of fields where they sometimes were hired by the landowners as day labourers but otherwise had to scrounge for their food (sometimes stealing grain from rats – which was why they’d come to be known as “rat eaters”).

There was a look of deadness in the eyes of the people there – a hopelessness and sense of fatalism. Our local hosts told us that these were the most marginalized people in the whole country. They were the lowest tribe of the lowest caste and so everyone in the village had been raised to believe that they had no more value than the rats that ran through their village.

There was a school not far from the village, but we could find only one boy who attended that school. Though everyone had access to the school, none of the parents were convinced their children were worthy of it.

It was a powerful lesson in what oppression and marginalization can do to people. In other equally poor villages (in Ethiopia, for example) I’d still noticed a sense of pride in the people. The Musahar people showed no sense of pride or self-worth. Essentially, they had been “gaslighted” to believe they were worthless and could ask for no more than what they had.

The next day, my traveling companions and I took a rest day instead of visiting another village. We had enough footage for the documentary we were working on and we needed a break from what was an emotionally exhausting trip.

My colleague, however, opted to visit the second village. He came back to the hotel with a fascinating story. In the second village, a local NGO had been working with the people to educate them about their rights as citizens of India. It hadn’t taken long and these people had a very different outlook on their lives and their values. They were beginning to rally, challenging their local government representatives to give them access to the welfare programs that should have been everyone’s rights (but that people in the first village had never been told about by the corrupt politicians who took what should have been given to the villagers). On the way back to the hotel, in fact, he’d been stopped by a demonstration where the body of a man who’d died of starvation had been laid out on the street to block traffic and call attention to the plight of the Musahar people.

The people in the second village were slowly beginning to understand that they were human and had a right to dignity and survival.

In the coaching and personal growth world that I now find myself in, there is much said about “finding our voices”, “stepping into our power”, and “claiming our sovereignty”. Those are all important ideas, and I speak of them in my work, but I believe that there is work that we need to do before any of those things are possible. Like the Musahar people, those who have been silenced need to be taught of their own value and their own capacity for change before they can be expected to impact positive change.

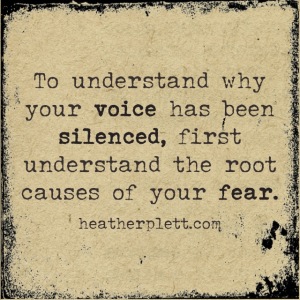

First we need to take a close look at the root causes of the fear that keeps us silent before we’ll be able to change the future.

When we begin to understand power and privilege, when we find practices that help us heal our ancient trauma, when we retrain our brains so that they don’t revert to their most primal conditioning, and when we find supportive communities that will encourage us in our attempts at courage, then we are ready to step into our power and speak with our strongest voices.

Like the Musahar, we need to work on understanding our own value and then we need to work together to have our voices heard.

These are some of the thoughts on my mind as I consider offering another coaching circle based on Pathfinder and/or Lead with Your Wild Heart. If you are interested in joining such a circle, please contact me.

Also, if you are longing to understand your own fear so that you can step forward with courage, consider joining me and Desiree Adaway at Engage!

Several years ago, I visited a village in the poorest part of India. Though I’d traveled in several poor regions in Bangladesh, India, and a few African countries before that, this was the most depressing place I’d ever visited. This was a makeshift village populated by the

Several years ago, I visited a village in the poorest part of India. Though I’d traveled in several poor regions in Bangladesh, India, and a few African countries before that, this was the most depressing place I’d ever visited. This was a makeshift village populated by the