by Heather Plett | Mar 24, 2016 | change, Christianity, Easter, journey, marriage

It’s Easter, the time of year when Christians celebrate the end and the beginning, the death and the resurrection. It is also Springtime, when that which was dead awakes and is renewed.

For the past six years, Easter has taken on special significance for me. In my own life, I too celebrate death and resurrection, beginning and end.

Six years ago, my family and I traveled north to my brother’s house for some time with my family of origin. It was while we were there that we learned that my mom had cancer. It was also there that the crack in my marriage became too big to ignore.

At the end of the evening, when we were all shell-shocked with the realization we might lose mom, my husband and I got into an argument. I knew suddenly, with painful clarity, that if things didn’t change, this marriage would end. On the long drive home, I told him, in low tones so the girls in the back of the van couldn’t hear, that if things didn’t change, the marriage would be over. By the time we’d gotten home, we’d agreed that the next step would be counselling.

Something else happened that weekend before we’d gone to my brother’s place. Sitting in church on Easter morning, I had the sudden realization that the church I’d called home for the past fifteen years no longer felt like the right place for me to find community. Though I still loved the people in the congregation, changes in the church and changes in me made me feel like I didn’t fit anymore.

Monday morning, I woke with a horrible sense of dread, knowing that I was standing on the precipice of destruction. Everything was crumbling and I stood to lose the two people closest to me – both my husband and my mom – and the community that had once been my greatest support. The ground underneath my feet suddenly felt like it had turned to quicksand.

On top of that, I was in the first faltering steps of growing a businesses, and wasn’t making much money at it yet, so I had very little security of any kind.

When I look back over the five years following that fateful Easter Sunday, what I remember most is struggle and resistance. I was struggling to keep everything from falling apart and resistant to the changes I was afraid were coming. My husband and I attended repeated rounds of marriage counselling in hopes of saving our marriage. Together with my siblings, I supported Mom as she went through surgery and repeated rounds of chemo. I joined a new leadership committee at church, hoping a renewed commitment might help me feel like I fit again. And all the while I was struggling to make my business viable and to be a good mom for my teenage daughters.

One by one, all that I’d feared that Easter Sunday fell apart. Mom died a year and a half after she was diagnosed. My marriage ended and I stopped going to church. Three for three.

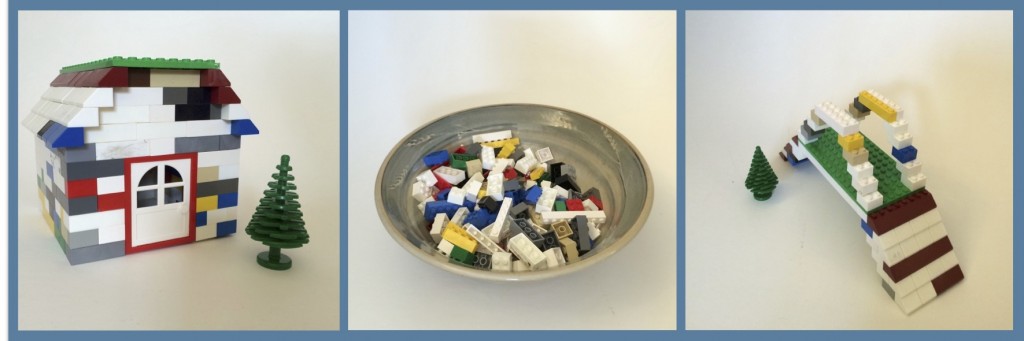

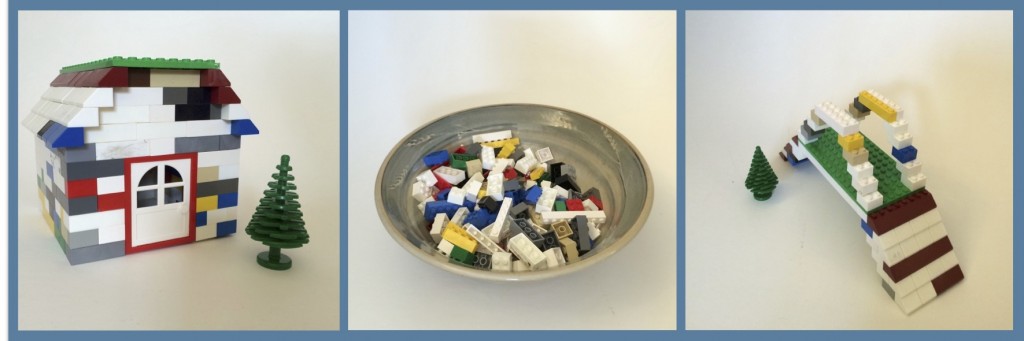

Yesterday, I was building some Powerpoint slides for a talk I’m giving in Kentucky next week, and I was looking for a visual metaphor for a point I want to make about how the work of holding space is very often the work of supporting destruction and regeneration. What I finally came up with can be seen in the photos below – a Lego house that is destroyed so that a bridge can be built out of the pieces.

As I was building it, I wasn’t focusing on how personal it felt, but now that I look at it, I see my own story. My life was like the house in the first picture – tidy and secure, with my mom, my husband, and my church standing as the walls that kept me safe. But a house wasn’t what was needed anymore. It had kept me safe and secure for the first half of my life, and for that I was grateful, but now I needed to step into a new story. Instead of the safety and security of a house, it was time to transform and embrace the possibility and risk of a bridge.

The transformation can’t happen without the destruction. That’s what the story of Easter teaches us.

What made me feel safe needed to be dismantled because it was also keeping me stuck. Safety meant that I wasn’t telling the truth. I wasn’t living authentically. I wasn’t stepping out in boldness. I was saying and doing the things I needed to say and do in order to keep everything from falling apart. I was letting fear guide me instead of courage.

But now that it’s all fallen apart and I discovered I was strong enough to live through the pain, I am receiving the gifts of the destruction.

I am living more boldly because I have less to lose. I am telling the truth because I know I can. I am living like each day matters because I know it can all end in a moment.

In the process, I am building new relationships and finding new community that feel increasingly more authentic and connected to who I am now. I don’t have time for shallowness anymore – I need depth and passion, and that’s what I’m pouring my energy and my heart into.

After the destruction, I am living a bigger, bolder, more beautiful life. I am crossing the bridge instead of staying stuck in the house. That’s the gift of falling apart.

Tomorrow is Good Friday, the day we focus on the death of Christ. It’s a sombre day that reminds us of our own endings, deaths, and failed dreams. But that’s not the end of the story. Just around the corner is Easter Sunday, the resurrection, the delight, the fulfillment.

If something is dying in your life, don’t fight it, let it go. Release it and trust, because just around the corner will be your chance to rise again, to be made new.

After the destruction comes the possibility.

* * * * *

If your life is falling apart, perhaps I can hold space for you with some coaching? If you’re rising from the ashes and are using your experience to help you hold space for others, join us in The Helpers’ Circle. If you’d like to explore how writing might support your transformation, there are two opportunities (one online and one in-person) to join the Openhearted Writing Circle.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my weekly reflections.

by Heather Plett | Sep 9, 2015 | circle, growth, journey, Labyrinth

This week, school is back in session. One of my daughters started today and the other two start tomorrow. Two are now in university and one is in grade 8, her last year before high school.

This week, school is back in session. One of my daughters started today and the other two start tomorrow. Two are now in university and one is in grade 8, her last year before high school.

I can say all of the clichéd things, and mean them… My how time flies! Wasn’t it just yesterday I was changing their diapers? How did it all rush past in the blink of an eye?

The return to school always reminds me of the relentless and dependable forward motion of time. Tick, tick, tick goes the clock. Flip, flip, flip go the pages of the calendar.

Today I was rushing out for last minute school supplies, haircut appointments, musical instrument rental, etc., and in the middle of it all, I wanted to hit the pause button. I wanted to slow down the pace of time, enjoy a few more summer days, and cling to my daughters’ fleeting childhood before it all disappears.

From my daughters’ perspective, still in their formative years, this is the way life is supposed to be lived – growing each year, advancing one grade after the other, stepping always forward on the straight line of time guided by the clock and the calendar. It’s the way we’re all raised – to believe that there is always meant to be forward movement. That’s not a bad thing – we want growth to happen.

But that’s only part of the truth and there’s something else I really want my daughters to learn that they probably won’t be taught in school.

Life is to be lived along the spiral and not simply the straight line.

When I was at the beach this summer, working on my book, I spent a lot of time watching pelicans. One of the things I love about pelicans is that, often, they fly across the sky in giant spirals, round and round, adjusting the arc of the spiral just enough each time so that they end at the far side of the sky from where they started.

They do this to conserve energy, riding thermals (updrafts of warm air that rise from the ground into the air), so they don’t have to flap their wings as often. They look so content and relaxed up there, circling round and round with very little effort on their part. High in the sky, they look like mythical creatures, as if they’d climbed out of ancient legends of magicians and shamans. Their shape and the way they move holds both mystery and myth.

That’s the path that I have come to believe is the most true way of seeing our lives. We go round and round, coming back each time to nearly the same place we’ve been, but always with enough of a difference to help us progress forward over time.

How many times have you been in this place you’re at right now? Like the seasons, our lives come back again and again to the harvest of Fall, the dormancy of Winter, the rebirth of Spring, and the growth of Summer. And, like the seasons, we live through the long dark spells, the slow sunny days, the rain, the wind, and the snow. We cycle through grief, through growth, through joy, through surrender, and through ease.

None of the seasons lasts forever. All of them change us a little before we begin the spiral again.

If you are in a place you feel like you’ve been before – whether it’s another cycle through grief, restlessness, waiting, or fear – don’t despair. You’re simply spiralling through the sky, learning what you need to from this trip around the circle, and moving a little further each time.

If you were traveling up a mountain, you’d be best to take the spiralling path, adjusting to the altitude, not tiring yourself out too quickly. Like the pelicans floating on the thermal air, you conserve your energy by not rushing straight ahead. You also learn more and see more that way. This is the way life is meant to be lived.

Don’t rush through, even though the path might seem hard right now. Take what you need from this time, and let it unfold in the fullness of time.

If you want to take a closer look at your own spiral path, I invite you to join us for the October offering of The Spiral Path: A Woman’s Journey to Herself.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Jun 3, 2015 | change, circle, Community, Compassion, growth, journey, Leadership

“…whenever I dehumanize another, I necessarily dehumanize all that is human—including myself.”

– from the book Anatomy of Peace

This week, I’ve been thinking about how we hold space when there is an imbalance in power or privilege.

This has been a long-time inquiry for me. Though I didn’t use the same language at the time, I wrote my first blog post about how I might hold space for people I was about to meet in Africa whose socio-economic status was very different from mine.

I had long dreamed of going to Africa, but ten and a half years ago, when I was getting ready for my first trip, I was feeling nervous about it. I wasn’t nervous about snakes or bugs or uncomfortable sleeping arrangements – I was nervous about the way relationships would unfold.

I was traveling with the non-profit I worked for at the time and we were visiting some of the villages where our funding had supported hunger-related projects. That meant that, in almost every encounter I’d have, I would represent the donor and they would be the recipients. I was pretty sure that those two predetermined roles would change how we’d interact. My desire to be in authentic and reciprocal relationship with them would be hindered by their perceived need to “keep the donor happy”.

That challenge was further exacerbated by:

- a history of colonization in the countries where I was visiting, which meant that my white skin would automatically be associated with the colonizers

- my own history of growing up in a church where white missionaries often visited and told us about how they were working in Africa to convert the heathens

In that first blog post, I wrestled with what it would mean to carry that baggage with me to Africa. I ended the post with this… I won’t expect that my English words are somehow endued with greater wisdom than theirs. I will listen and let them teach me. I will open my heart to the hope and the hurt. I will tread lightly on their soil and let the colours wash over me. I will allow the journey to stretch me and I will come back larger than before.

In another blog post, after the trip, I wrote about how hard it was to find the right words to say to the people who’d gathered at a food distribution site…What can I say that is worthy of this moment? How can I assure them I long for friendship, not reverence?

That trip, and other subsequent ones to Ethiopia, India, and Bangladesh, stretched and challenged me. Each time I went, I wrestled with the way that my privilege and access to power would change my interactions. I became more and more intentional about entering into relationships with humility, grace, and openheartedness. I did my best to treat each person with dignity and respect, to learn from them, and to challenge my own assumptions and prejudice.

Nowadays, I don’t have the same travel opportunities, but I still find myself in a variety of situations in which there is imbalance. Sometimes I have been the one with less privilege and power (like when I used to work in corporate environments with male scientists, or when I traveled with and offered support to mostly male politicians). Other times, I have access to more power and/or privilege than others in the room (like when I am the teacher at the front of the classroom, or I am meeting with people of Indigenous descent). In each situation, I find myself aware of how the imbalance impacts the way we interact.

This week in Canada, the final report on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s findings related to Residential Schools has come out and it raises this question for all of us across the country. Justice Murray Sinclair, chair of the commission, has urged us to take action to address the cultural genocide of residential schools on aboriginal communities. Those are strong words (and necessary, I believe) and they call all of us to acknowledge the divide in power and privilege between the Indigenous people and those of us who are Settlers in this nation.

How do we hold space in a country in which there has been genocide? How do we who are settlers acknowledge our own privilege and the wounds inflicted by our ancestors in an effort to bring healing to us all?

This is life-long learning for me, and I don’t always get it right (as I shared after our first race relations conversation), but I keep trying because I know this is important. I know this matters, no matter which side of the power imbalance I stand on.

If we want to see real change in the world, we need to know how to be in meaningful relationships with people who stand on the other side of the power imbalance.

Here are some of my thoughts on what it takes to hold space for people when there is a power imbalance.

- Don’t pretend “we’re all the same”. White-washing or ignoring the imbalance in the room does not serve anyone. Acknowledging who holds the privilege and power helps open the space for more honest dialogue. If you are the person with power, say it out loud and do your best to share that power. Listen more than you speak, for example, or decide that any decisions that need to be made will be made collectively. If you lack power, say that too, in as gracious and non-blaming a way as possible.

- Change the physical space. It may seem like a small thing to move the chairs, to step away from the podium, or to step out from behind a desk, but it can make a big difference. A conversation in circle, where each person is at the same level, is very different from one in which a person is at the front of the room and others are in rows looking up at that person. In physical space that suggests equality, people are more inclined to open up.

- Invite contribution from everyone. Giving each person a voice (by using a talking piece when you’re sharing stories, for example) goes a long way to acknowledging their dignity and humanity. Allowing people to share their gifts (by hosting a potluck, or asking people to volunteer their organizational skills, for example) makes people feel valued and respected.

- Create safety for difficult conversations. When you enter into challenging conversations with people on different sides of a power imbalance, you open the door for anger, frustration, grief, and blaming. Using the circle to hold such conversations helps diffuse these heightened emotions. Participants are invited to pour their stories and emotions into the center instead of dumping them on whoever they choose to blame.

- Don’t pretend to know how the other person feels. Each of us has a different lived experience and the only way we can begin to understand what another person brings to the conversation (no matter what side of the imbalance they’re on) is to give them space to share their stories. Acting like you already know how they feel dismisses their emotions and will probably cause them to remain silent.

- Offer friendship rather than sympathy. If you want to build a reciprocal relationship, sympathy is the wrong place to start. Sympathy is a one-way street that broadens the power gap between you. Friendship, on the other hand, has well-worn paths in both directions. Sympathy builds power structures and walls. Friendship breaks down the walls and puts up couches and tables. Sympathy creates a divide. Friendship builds a bridge.

- Even if you have little access to power or privilege, trust that your listening and compassion can impact the outcome. I was struck by a recent story of how a group of Muslims invited anti-Muslim protestors with guns into their mosque for evening prayers. An action like that can have significant impact, cracking open the hearts of those who’ve let themselves be ruled by hatred.

- Don’t be afraid to admit that you don’t know the way through. Real change happens only when there is openness to paths that haven’t been discovered yet. If you walk into a conversation assuming you know how it needs to turn out, you won’t invite authenticity and openness into the room. Your vulnerability and openheartedness invites it in others.

- Don’t try this alone. This kind of work requires strong partnerships. People from all sides of the power or privilege divide need to not only be in the conversation, but be part of the hosting and planning teams. That’s the only way to ensure all voices are heard and all cultural sensitivities are honoured.

I welcome your thoughts on this. What have you found that makes a difference for conversations where there is an imbalance?

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Apr 1, 2015 | beginnings, grief, growth

“Treating ourselves like appliances that can be unplugged and plugged in again at will or cars that stop and start with the twist of a key, we have forgotten the importance of fallow time and winter and rests in music. We have abandoned a whole system of dealing with the neutral zone through ritual, and we have tried to deal with personal change as though it were a matter of some kind of readjustment.” – William Bridges

One of the women in my women’s circle shared recently that she has a hard time explaining to her husband where she goes every Thursday. “He just doesn’t get it,” she said. “He keeps asking ‘But… what do you do there? What’s the purpose?’ He can’t understand why we’d want to sit in a circle and share stories of our lives when we’re not accomplishing anything or learning anything.”

This is a common story in my work. “But what will we do?” people ask when I talk about my retreats, workshops, or even coaching sessions. I talk about making mandalas, walking labyrinths, and sitting in conversation circles, but that’s often not enough for people who believe life is only valuable when we’re doing/accomplishing/fixing/building/growing/learning something.

We have created a culture in which busy = important, accomplishment = valuable, and idleness = wasting time. Even when we go away for retreat or sit in circle, we think we have to be able to name what we accomplished in our time away. If we don’t have a checklist of “things we got done” then the time wasn’t valuably invested. To say we simply wandered in the woods for a few days is the equivalent of admitting we’re lazy and unproductive and that we can’t be trusted to contribute to society.

We fear laziness, we chafe at lack of productivity, and we hide in shame when we take too long to “get over things”.

We have become a society that has lost the capacity for spaciousness in our transitions.

Take grief, for example. We think if we can name the “five stages of grief”, then we’ll be able to clean up the process, hide the messiness, and get through it faster.

Birth is the same. In many cultures, a mother is expected to return to “productive” work only weeks after the biggest life-changing event she’s ever gone through.

And those are the “big” ones. When it comes to “smaller” transitions (changing careers, ending relationships, having a car accident, etc.), we’re hardly even given permission to talk about them, let alone experience the full weight of them in our lives. There are more important things to do than to sit around in sharing circles talking about the hard things life has thrown our way.

In one of the best books I’ve read on the subject, Transitions, William Bridges calls the space between the ending of one phase of our lives and the beginning of another “the neutral zone”. Some time around the industrial revolution, we lost touch with the neutral zone.

“In other times and places the person in transition left the village and went out into an unfamiliar stretch of forest or desert. There the person would remain for a time, removed from the old connections, bereft of the old identities, and stripped of the old reality. This was a time ‘between dreams’ in which the old chaos from the beginnings welled up and obliterated all forms. It was a place without a name – an empty space in the world and the lifetime within which a new sense of self could gestate.”

Again and again in my coaching work, I find myself in conversation with people who fear the neutral zone. When we begin the conversation, they talk about some big change they feel they need to make in their lives and they express frustration about their lack of ability to get there quickly and easily. “What’s wrong with me?” they almost always say. “I know that it’s time for change, but I can’t seem to find clarity or drive to get me to the next stage of my life. I feel like I’m stuck in quicksand.” Again and again they beat themselves up for not living up to some arbitrary expectation they’ve placed on themselves or they feel others are placing on them.

Somewhere in the middle of the first conversation, I nudge them to give themselves permission to “just be lost” for awhile. Usually, there s some resistance to this. Lostness is not something they’ve ever been taught to value. Lostness = unworthiness.

By the second or third conversation, most have spoken aloud their desire for more spaciousness. “I just feel like making art for awhile” or “I just need to learn to give myself permission to feel this grief deeply” or “I’m going to take a few months just to ‘be’ and not ‘do’.”

It’s remarkably hard to get to that place of spaciousness and acceptance. Sometimes it’s even hard for me, as a coach, to invite them into that place. The voices in my head often remind me “They’re paying you good money for this – shouldn’t you help them accomplish something? Shouldn’t you do something more valuable than give them permission to just be for awhile?”

That moment of doubt always passes though, when I remember how crucial it is for us to transition well and to honour the neutral zone before we step into the new beginning. If I give my clients nothing else but the permission to honour their own timing in their transitions, then I have done well.

What we don’t realize, when we rush through the neutral zone, is that we’re short-circuiting real growth. If we deny ourselves of the fallow time, the winter season when seeds lie dormant underground, then our growth will be stunted and unhealthy, and, more often than not, the emotions we denied ourselves will emerge in less healthy ways later in our lives.

We need the neutral zone and we need to honour and give space for it in others as well.

A bamboo plant spends three or four years growing a good root system before anything emerges above the ground. In the same way, we need to invest in our rootedness before the growth will be obvious to anyone else. We need to create the space and time to “just be” before we are ready to “do”.

Learn to create spaciousness in your life by giving yourself permission to wander in the woods, to make messy art, to stare into space, to sit in long conversations with friends, to feel emotions deeply, to savour good food, to say no to some of your commitments, or to go on a pilgrimage or vision quest.

This is not time “wasted”, it’s time well invested in your own growth and well-being.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Jan 28, 2015 | art of hosting, change, growth, journey, Leadership

“The success of our actions as change-makers does not depend on what we do or how we do it, but on the inner place from which we operate.” – Otto Sharmer

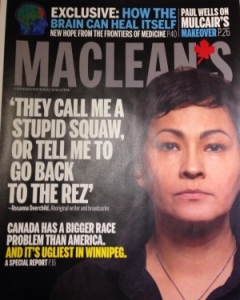

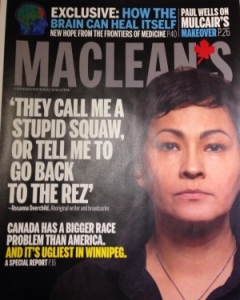

Last week, the city that I love and call home was named “the most racist city in Canada.” That hurt. It felt like someone had insulted my family.

Last week, the city that I love and call home was named “the most racist city in Canada.” That hurt. It felt like someone had insulted my family.

The article mentions many heartbreaking stories of the way that Indigenous people have been treated in our city, and while I wanted to say “but… we’re so NICE here! Really! You have to see the other side too!” I knew that there was undeniable truth I had to face and own. My family isn’t always nice. Neither is my city.

Though I work hard not to be racist, have many Indigenous friends in my circles, and am married to a Metis man, I knew that my response to the article needed to not only be a closer look at my city but a closer look at myself. I may not be overtly racist, but are there ways that I have been complicit in allowing this disease to grow around me? Are there things that I have left unsaid that have given people permission for their racism? Are there ways in which my white privilege has made me blind?

Ever since the summer, when I attended the vigil for Tina Fontaine, a young Indigenous woman whose body was found in the river, I have been feeling some restlessness around this issue. I knew that I was being nudged into some work that would help in the healing of my city and my country, but I didn’t know what that work was. I started by carrying my sadness over the murdered and missing Indigenous women into the Black Hills when I invited women on a lament journey.

Ever since the summer, when I attended the vigil for Tina Fontaine, a young Indigenous woman whose body was found in the river, I have been feeling some restlessness around this issue. I knew that I was being nudged into some work that would help in the healing of my city and my country, but I didn’t know what that work was. I started by carrying my sadness over the murdered and missing Indigenous women into the Black Hills when I invited women on a lament journey.

This week, after the Macleans article came out, our mayor made a courageous choice in how he responded to the article. In a press conference called shortly after the article spread across the internet, he didn’t get defensive, but instead he spoke with vulnerability about his own identity as a Metis man and about how his desire is for his children to be proud of both of the heritages they carry – their mother’s and his. He then invited several Indigenous leaders to speak.

There was something about the mayor’s address that galvanized me into action. I knew it was time for me to step forward and offer what I can. I sent an email and tweet to the mayor, thanking him for what he’d done and then offering my expertise in hosting meaningful conversations. Because I believe that we need to start healing this divide in our city and healing will begin when we sit and look into each others’ eyes and listen deeply to each others’ stories.

After that, I purchased the url letstalkaboutracism.com. I haven’t done anything with it yet, but I know that one of the things I need to do is to invite more people into a conversation around racism and how it wounds us all. I have no idea how to fix this, but I know how to hold space for difficult conversations, so that is what I intend to do. Circles have the capacity to hold deep healing work, and I will find a way to offer them where I can.

Since then, I have had moments of clarity about what needs to be done next, but far more moments of doubt and fear. At present, I am sitting with both the clarity and the doubt, trying to hold both and trying to be present for what wants to be born.

Here are some of the things that are showing up in my internal dialogue:

- Isn’t it a little arrogant to think I have any expertise to offer in this area? There are so many more qualified people than me.

- What if I offend the Indigenous people by offering my ideas, and become like the colonizers who think they have the answers and refuse to listen to the wisdom of the people they’re trying to help?

- There are already many people doing healing work on this issue, and many of them are already holding Indigenous circles. I have nothing unique to contribute.

- What if I host sharing circles and too much trauma and/or conflict shows up in the circle and I don’t know how to hold it?

- What if this is just my ego trying to do something “important” and get attention for me rather than the cause?

And so the conversation in my head goes back and forth. And the conversations outside of my head (with other people) aren’t much different.

At the same time as this has been going on, I have been working through the first two weeks of course material for U Lab: Transforming Business, Society and Self. In one of the course videos, Otto Sharmer talks about the four levels of listening – from downloading (where we listen to confirm habitual judgements), to factual (listening by paying attention to facts and to novel or disconfirming data), to empathic (where we listen with our hearts and not just our minds), and finally to generative (where we move with the person speaking into communion and transformaton).

As soon as I read that, I knew that whatever I do to help create space for healing in my city, it has to start with a place of deep listening – generative listening, where all those in the circle can move into communion and transformation. I also knew, as I sat with that idea, that that generative listening has to begin with me.

If I am to serve in this role, I need to be prepared to move out of my comfort zone, into generative listening with people who have been wounded by racism in our city AND with people who live with racial blindspots. AND (in the words of Otto Sharmer) I need to move out of an ego-system mentality (where I am seeking my own interest first), into a generative, eco-system mentality (where I am seeking the best interest of the community and world around me).

So that is my intention, starting this week. I already have a meeting planned with an Indigenous friend who has contributed to, and wants to teach, an adult curriculum on racism, to find out how I can support her in this work. And I will be meeting with another friend, a talented Indigenous musician, about possible partnership opportunities. And I will be a sitting in an Indigenous sharing circle, listening deeply to their stories.

I am not sharing these stories to say “look at me and all of the good things I’m doing”. That would be my ego talking, and that’s one of the things I’m trying to avoid. Instead, I’m sharing it to say “look at the complexity that a thinking woman (sometimes over-thinking woman) goes through in order to become an effective, and humble, change-maker.

That brings me back to the quote at the top of the page.

“The success of our actions as change-makers does not depend on what we do or how we do it, but on the inner place from which we operate.” – Otto Sharmer

The inner place. That is what will determine the success of our actions. I can have all the smart ideas in the world, and a big network of people to help roll them out, but if I have not done the internal work first, my success will be limited.

If I don’t do the inner work first, then my ego will run rampant and I will stomp all over the people that I say I care about. Or I will suffer from jealousy, or self doubt, or self-centredness, or vindictiveness, or all of the above.

If I don’t do the internal work and ask myself important questions about what is rooted in my ego and what is generative, then I could potentially do more harm than good.

So how do I do that internal work? Here are some of the things that I do:

1. As we say in Art of Hosting work, I host myself first. In other words, I ask of myself whatever I would ask of others I might invite into circle, I look for both my shadows and my strengths, and I do the kind of self-care I would encourage my clients to do when they find themselves in the middle of big shifts.

2. I ask myself a few pointed questions to determine whether the ego is too involved. For example, when my friend came to me to share the work she wants to do, hosting circles in the curriculum she has developed, there was a little ego-voice that spoke up and said “But wait! This was supposed to be YOUR work! If you support her, you’ll have to be in the background.” The moment I heard that voice, I had to ask myself “do you truly want to make a difference around the issue of racism or do you just want to make a name for yourself?” And: “If this is successful in impacting change, but you have only a secondary role, is it still worthwhile?” It didn’t take long for me to know that I wanted to be wholeheartedly behind her work.

3. I pause. As we learn in Theory U, the pause is the most important part – it’s where the really juicy stuff happens. The pause is where we notice patterns that we were too busy to notice before. It’s where the voice of wisdom speaks through the noise. It’s where we are more able to sink into generative listening. In Theory U, we call it “presencing” – a combination of “presence” and “sensing”. There’s a quality of mindfulness in the pause that helps me notice and experience more and be awake to receive more wisdom.

4. I do the practices that help bring me to wise thought and wise action. For me, it’s journaling, art, mandala-making, nature walks, and labyrinth walks. I never make a major decision without spending intentional time in one of those practices. Almost always, something more profound and wise shows up that I wouldn’t have considered earlier.

5. I listen. The ego doesn’t want me to seek input from other people. The ego wants to be in control and not invite partners in to share the spotlight. If I want to move out of ego-system, though, I need to spend time listening for others’ stories and wisdom. This doesn’t mean I listen to EVERYONE. Instead, I use my discretion about who are the right people to seek wise council from. I listen to those who have done their own personal work, whose own egos won’t try to trap me and keep me from succeeding, and who genuinely care about the issue I’m working on.

6. I check in with myself and then move into action when I’m ready. Although the pause, the questions, and the personal practice are all very important, the movement into action is equally important. There have been far too many times when my questions and ego have trapped me in a spiral and I’ve failed to move into action. Just thinking about it won’t impact change. I need to be prepared to act, even if I still have doubt. If I fail in that action, I can always go back and re-enter the presencing stage.

This is an ongoing story and I hope to continue sharing it as it emerges. If you, too, want to become a change-maker, then I’d love to hear from you. What are the processes you go through in order to ensure your “inner place” is healthy and your listening and actions are generative? What issues are currently calling you into action?

If this resonates with you, check out The Spiral Path, which begins February 1st. Based on the three stages of the labyrinth, (release, receive, and return), it invites you to go inward to do this internal work and then to move outward to serve in the way that you are called.

Also… we’re looking for a few more change-makers to attend Engage, a one-of-a-kind retreat that will teach you more about how to do your inner work so that you can move into generative action.