by Heather Plett | Apr 27, 2017 | holding space, Labyrinth, Uncategorized

The Way It Is

There’s a thread you follow. It goes among

things that change. But it doesn’t change.

People wonder about what you are pursuing.

You have to explain about the thread.

But it is hard for others to see.

While you hold it you can’t get lost.

Tragedies happen; people get hurt

or die; and you suffer and get old.

Nothing you do can stop time’s unfolding.

You don’t ever let go of the thread.

~ William Stafford ~

In order to ensure that Theseus would find his way back out of the labyrinth (which he entered in order to slay the minotaur and free his people), Ariadne gave him a ball of thread that he could unravel on the way in and follow on the way out.

Much of my life feels like a version of Theseus’ journey and Stafford’s poem. I’ve been following a thread that’s hard for others to see, but that keeps me from getting lost even when tragedies happen and people get hurt. Stumbling through a dark labyrinth, I often can’t see more than five feet in front of me, but I can feel the light touch of the thread in my hand that invites me forward.

A conversation with a client yesterday reminded me of this thread and how it has sustained me over the years. She was lamenting the fact that, unlike others who seem so focused on their goals, she could never see a clear vision for her life or her work. She had lots of interests and passion, but couldn’t seem to shape those into a business plan or “elevator speech” that would help her make sense of her work to other people. On top of that, grief had rearranged her recently, so she barely recognized herself some days.

The conversation reminded of the time, five years ago, when I was in a similar place. Back in 2012, when I was still struggling to make this business viable, my mom was dying and my marriage was crumbling. I was afraid, angry, and lost. Any vision I thought I’d had for my unfolding future seemed like nothing more than a mirage that had vanished from the horizon. I’d started looking for part time work, afraid I was failing at self-employment because I hadn’t mastered those things the business experts tell you to do, like envisioning my target audience, having clear goals, or writing solid business plans.

Up until that time, I’d often made vision boards, like many good life coaches do, collecting and collaging visual images that represent my unfolding vision. But that process, like so many others, had failed me. No matter how many vision boards I made, my work still felt unfocused and my future was still a mirage. The pending death of my mom and my marriage only compounded the situation.

Frustrated and angry, and feeling betrayed by the practices I’d adopted and coached other people to use, I turned to destruction. I started tearing up maps. Here’s what I wrote at the time:

Tearing up old maps can feel surprisingly cathartic when there’s no roadmap for the journey you’re traveling along. I tore and I placed and I glued. I shredded roads and lined them up with wasteland. I tore up countries and provinces. I cut lakes in half. I destroyed international borders. I had no idea what was emerging, but it felt good to destroy.

What emerged from that was the most helpful collage I’ve ever made – my lack-of-vision board. (The above image.) It was messy and beautiful, with glimpses of the thread I keep hanging onto even when I couldn’t see my way out of the labyrinth.

I’ve never made another vision board since. The lack-of-vision board works better for me – helping me sit in the messiness and practice mindfulness even when I feel lost. The vision board always felt a little forced – like I was trying to bash down the walls of the labyrinth so that I could see where the path was going to take me. Instead, my practice is to hold the thread lightly in my hand and trust that one foot in front of another is the only way to follow the path.

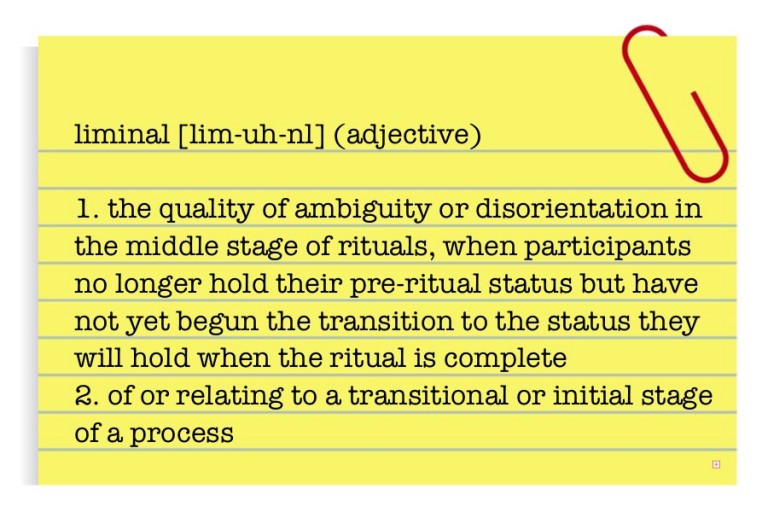

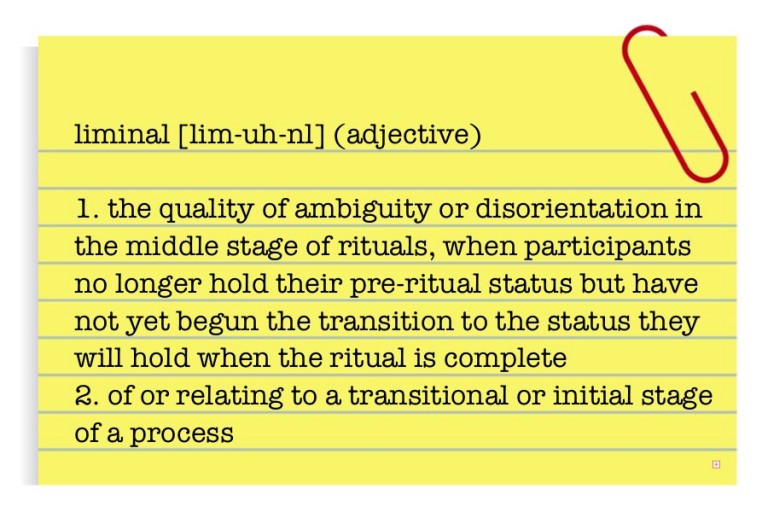

Now, when I look back at the development of my work, I can see that moments like this, when I tore up the map and made meaning out of the mess, were the pivotal moments when my real work was emerging. I was learning to surrender to the liminal space. I was letting go of the vision I thought I should have and letting go of the way I thought I should do my work (in other words, the ways that seemed conventionally acceptable). Instead, I was learning to trust the path as it emerged from the shadows in front of me.

When I coach people now, it looks different from what it did in those early days. I’ve let go of many of the conventions of what coaching is supposed to be and I’ve learned that those liminal spaces are where the really important work happens.

Many in the personal development field want to rush you through those places and into more productivity, light and positive thoughts, but my work is different from that. It’s about holding space for people while they learn to sit with the questions and work through their discomfort with the liminal space.

I couldn’t always tell you what the thread was, back in those moments when I felt lost and confused, but now, when I look back at the places I’ve been, I can see that the thread was there and it helped me get to where I am now. The thread finally became clear when, after my mom died, I wrote the blog post about holding space that went viral and changed my work forever.

All of that time when I was walking through loss and grief and liminal space, I was doing the hard learning that brought me to where I am now.Surrendering to the experience is what allowed me to develop the body of work that is now emerging in my Holding Space Coach/Facilitator Program. Though none of it felt focused at the time, and, as Stafford says, “people wondered about what I was pursuing,” in retrospect I can see that it all threaded together and made a remarkable amount of sense.

Preparing this program has felt like stepping out of the labyrinth into a clear sunny day.

I had to go through all of that to see that what I was meant to develop was not the same kind of coaching or facilitation work that has become common in the personal development world. It is something different, something deeper – something that doesn’t run from complexity, grief, or discomfort but learns to make meaning of it instead.

This work is counter-cultural and doesn’t always make sense in a culture that values linear progress and simple answers, but it’s clear that it responds to a hunger people hardly know they have. When people finally give themselves permission to feel lost, and they no longer feel so alone in the lostness, there’s a new light in their eyes that wasn’t there before.

I am looking forward to working with the participants of the Holding Space Coach/Facilitator Program, because I know that they will bring much wisdom and curiosity to the work. Those who join me will be people who, like me, have walked through pain and grief and despair and have found the source of their own resilience. They will be people who’ve learned to sit with the questions without rushing to find answers. They will be meaning-makers and mystics who embrace the mystery and complexity of life. They will be those who understand what it’s like to stumble through the labyrinth, trusting that the fragile thread in their hand will guide them through the darkness.

This is not a linear path we’re on and there are no easy answers, but when you follow the thread, you can find your way through. Join me?

* * * * *

The Holding Space Coach/Facilitator Program is a new online training program, built in a modular way that offers something for everyone who holds space. Register now for the first session which begins May 29th.

If you are looking for coaching for your own liminal space, sign up now as I will only be receiving new clients for the next 2 weeks. After that, the doors will be closed for several months while I work on the new training program.

by Heather Plett | Oct 5, 2016 | holding space, Leadership

“Can’t you just give us clear direction so we know what’s expected of us?” That question was asked of me ten years ago by a staff person who was frustrated with my collaborative style of leadership. He didn’t want collaboration – he simply wanted direction and clarity and top-down decision making.

What I read between the lines was this: “It makes me feel more safe when I know what’s expected of me.” And maybe a little of this: “If you’re the one making decisions and giving directions, I don’t have to share any collective responsibility. If anything goes wrong, I can blame the boss and walk away with my reputation intact.”

I didn’t change my leadership style, but it made me curious about what different people want from leadership and why. While that staff person was expressing a desire for more direction, others on my team were asking for more autonomy and decision-making power. It seemed impossible to please everyone.

I’ve been thinking back to that conversation lately as I watch the incredulous rise to power of Donald Trump. No matter how many sexist or racist comments he makes, no matter how many people with disabilities he makes fun of, and no matter how many small business owners he’s cheated, his support base remains remarkably solid. As he himself has said, he “could shoot someone and not lose votes”. (I’m glad I’m no longer teaching a course on public relations, because he’s breaking all of the “rules” I used to teach and getting away with it.)

It seems implausible that this could happen, but this article on Trump’s appeal to authoritarian personalities helps me make sense of it.

“‘Trump’s electoral strength — and his staying power — have been buoyed, above all, by Americans with authoritarian inclinations,’ political scientist Matthew MacWilliams wrote in Politico. In an online poll of 1,800 Americans, conducted in late December, he found an authoritarian mindset — that is, belief in absolute obedience to authority — was the sole ‘statistically significant variable’ that predicted support for Trump.”

“Authoritarians obey,” says the author of the study, “They rally to and follow strong leaders. And they respond aggressively to outsiders, especially when they feel threatened.”

Authoritarians hold strong values around safety, and they expect a leader to give them what they need. They don’t mind following a bully, as long as that bully is serving THEIR needs for security. Hence the popularity of Trump’s proposals to build a wall on the Mexican border and to keep Muslims from entering the country, and the way his supporters cheered when he told security to throw the protestors out of the places where he was campaigning. He makes his supporters feel safe because he won’t hesitate to rough up “the enemy”. They might even put up with some of the bullying directed at people like them (hence the surprising tolerance of Trump’s behaviour among his female supporters) if it means those who threaten them are kept at bay.

Where does an authoritarian mindset come from? According to the article quoted above, there is evidence that it is passed down from one generation to the next. Religious views can also play a strong role. Those who were conditioned by upbringing and religion to obey the authority figures at all cost are more likely to vote for someone who reflects that kind of leadership. If you grew up never allowed to question authority, no matter how illogical or unbalanced it might seem, then you are more likely to have an authoritarian mindset.

There is also a correlation with how fearful a person tends to be. Those who are, due to personality and/or conditioning, frequently motivated by fear, will be more inclined to trust an authoritarian leader because the clear boundaries such a person establishes is what makes them feel more safe.

Also, it cannot be denied that an authoritarian mindset is associated with a lack of emotional and spiritual development. As Richard Rohr says in Falling Upward: A Spirituality for the Two Halves of Life, those who still cling to the black and white, right and wrong of authoritarianism are choosing to stay stuck in the first half of life. “In the first half of life, success, security, and containment are almost the only questions. They are the early stages in Maslow’s ‘hierarchy of needs.’ We all want and need various certitudes, constants, and insurance policies at every stage of life.” Stepping into “second-half-of-life” involves a lot more grey zones and ambiguity, so it’s a more frightening place to be.

Does it matter that some of us prefer authoritarian leadership over other styles? Shouldn’t the rest of us simply adapt a “live and let live” attitude about it and not try to change people? Don’t we all have a right to our own opinions?

Though I am deeply committed to holding space for people in a non-judgemental way (and I tried to create that environment when I was leading the people I mentioned above) I am convinced that it DOES matter. Yes, we should respect and listen without judgement to those who look for authoritarianism, and we should seek to understand their fear, but that doesn’t mean that we should allow their fear and social conditioning to make major decisions about who leads us and how we are lead. That authoritarian mindset is a sign of an immature society and it is holding us back. It must be challenged for the sake of our future.

Around the same time as my staff person asked for more authoritarian leadership from me, I was immersing myself in progressive teachings on leadership such as The Circle Way, The Art of Hosting, and Theory U. These methodologies teach that there is a “leader in ever chair”, that the “wisdom comes from within the circle”, and that “the future is emerging and not under our control”. Though these models can (and do) function within hierarchical structures, they teach us to value the wisdom and leadership at ALL levels of the hierarchy.

Margaret Wheatley and Deborah Frieze (two people I had the pleasure of studying with in my quest for a deeper understanding about leadership), in this article on Leadership in the Age of Complexity and in their book Walk Out Walk On, say that it is time to move from “leader as hero” to “leader as host”.

“For too long, too many of us have been entranced by heroes. Perhaps it’s our desire to be saved, to not have to do the hard work, to rely on someone else to figure things out. Constantly we are barraged by politicians presenting themselves as heroes, the ones who will fix everything and make our problems go away. It’s a seductive image, an enticing promise. And we keep believing it. Somewhere there’s someone who will make it all better. Somewhere, there’s someone who’s visionary, inspiring, brilliant, trustworthy, and we’ll all happily follow him or her.”

This style of leadership may have served humanity during a simpler time, but that time is past. Now we are faced with so much complexity that we cannot rely on an outdated style of leadership.

“Heroic leadership rests on the illusion that someone can be in control. Yet we live in a world of complex systems whose very existence means they are inherently uncontrollable. No one is in charge of our food systems. No one is in charge of our schools. No one is in charge of the environment. No one is in charge of national security. No one is in charge! These systems are emergent phenomena—the result of thousands of small, local actions that converged to create powerful systems with properties that may bear little or no resemblance to the smaller actions that gave rise to them. These are the systems that now dominate our lives; they cannot be changed by working backwards, focusing on only a few simple causes. And certainly they cannot be changed by the boldest visions of our most heroic leaders.”

Instead of heroes, we need hosts. A leader-as-host knows that problems are complex and that in order to understand the full complexity of any issue, all parts of the system need to be invited in to participate and contribute. “These leaders‐as‐hosts are candid enough to admit that they don’t know what to do; they realize that it’s sheer foolishness to rely only on them for answers. But they also know they can trust in other people’s creativity and commitment to get the work done.”

A leader-as-host provides conditions and good group process for people to work together, provides resources, helps protect the boundaries, and offers unequivocal support.

In other words, a host leader holds space for the work to happen, for the issues to be wrestled with, and for the emergence of what is possible from within the circle.

Unlike a host leader, an authoritarian leader hangs onto the past as a model for the future. Consider Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan. Instead of holding space for emergence, he knows that his support base clings to the ideal of a simpler, more manageable time. It’s not hard to understand, in this time of complexity, how it can feel more safe to harken back to the past when less was expected of us and the boundaries were more clear (even if that meant more racism and less concern for our environment). Don’t we all, for example, sometimes wish we could be back in our childhood homes when all that was expected of us was that we clean up our toys before bedtime?

But we “can’t go back home again”. The future will emerge with or without us. We can only hope that the right kind of leadership can and will arise (within us and around us) that will help us adapt and grow into it. If not, our planet will suffer, our marginalized people will continue to be disadvantaged, and justice will never be served for those who have been exploited.

In his book, Leading from the Emerging Future, Otto Scharmer talks about leadership not being about individuals, but about the capacity of the whole system. “The essence of leadership has always been about sensing and actualizing the future. It is about crossing the threshold and stepping into a new territory, into a future that is different from the past. The Indo-European root of the English word leadership, leith, means ‘to go forth,’ ‘to cross a threshold,’ or ‘to die.’ Letting go often feels like dying. This deep process of leadership, of letting go and letting the new and unknown come, of dying and being reborn, probably has not changed much over the course of human history. The German poet Johan Wolfgang von Goethe knew it well when he wrote, ‘And if you don’t know this dying and birth, you are merely a dreary guest on Earth.’”

What he’s talking about is essentially the liminal space that I wrote about in the past. It’s the space between stories, when nobody is in control and the best we can do is to hold space for the emerging future. We, as a global collective, are in that liminal space in more ways than one and we need the leaders who are strong enough to support us there.

With Wheatley and Scharmer, I would argue that an important part of our roles as leaders in this age of complexity is to hospice the death of our old ideas about leadership so that new ideas can be born. Authoritarianism will not serve us in the future. It will not help us address the complexity of climate change. It will not help us address racial or gender inequity.

We need leaders – at ALL levels of our governments, institutions, communities, and families – who can dance with complexity, play with possibility, and sit with their fear. We need leaders who can navigate the darkness. We need leaders who can hold seemingly opposing views and not lose sight of the space in between. We need leaders who know how to hold liminal space.

This is not meant to be a political post, and so I won’t tell you who to vote for (partly because I am Canadian and partly because I’m not sure any candidate in any election I’ve witnessed truly reflects the kind of leadership I’m talking about – they are, after all, products of a system we’ve created which may no longer work for the future).

Instead, I will ask you… how is this style of leadership showing up in your own life? Are you serving as host or hero? Are you holding space for the emerging future? And are you asking it of the leaders that you follow and/or elect? Or are you still clinging to the past and hoping the right hero will ride in on a white horse to save us?

It’s time to stop waiting. There are no heroes who can save us. There is only us.

* * * * * *

Note: If you’re interested in exploring more about what it means to have “a leader in every chair”, consider joining me and my colleague, Sharon Faulds, for a workshop on The Circle Way, November 24-26.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my bi-weekly reflections.

by Heather Plett | Sep 20, 2016 | grief, growth, holding space, Intuition, journey, Uncategorized

My baby died before I got to hold him in my arms. I’d been in the hospital for three weeks, trying to save my third pregnancy, but then one morning I went downstairs for my twice-daily ultrasound and found out he had died while I slept. Then came the horrible and unavoidable realization… I had to give birth to him. For three hours I laboured, knowing that at the end of it, instead of a baby suckling at my breast, I would hold death in my arms. That’s the hardest kind of liminal space I’ve ever been through – excruciating pain on top of excruciating grief.

Yes, it was hard, but it was also one of the most tender, beautiful, grace-filled experiences of my life. It changed me profoundly, and set me on the path I am on now. That was the beginning of my journey to understanding the painful beauty of grief, the value of the liminal space, and the essence of what it means to hold space for another person.

When Matthew was born, the nurses in the hospital handled it beautifully. They dressed him in tiny blue overalls and wrapped him in a yellow blanket, lovingly hand-made by volunteers. They took photos of him for us to take home, made prints of his hands and feet for a special birth/death certificate, and then brought him to my room so that we could spend the evening with him. I asked one of the nurses later how they’d known just the right things to do, and she told me that they used to be frustrated because they didn’t know how to support grieving parents, but then had all been sent to a workshop that gave them some tools that changed the experience for the parents and for them.

That evening, our family and close friends gathered in my hospital room to support us and to hold the baby that they had been waiting to welcome.

Now, nearly sixteen years later, I don’t remember a single thing that was said in that hospital room, but I remember one thing. I remember the presence of the people who mattered. I remember that they came, I remember that they gazed lovingly into the face of my tiny baby, and I remember that they cried with me. I have a mental picture in my mind of the way they loved – not just me, but my lifeless son. That love and that presence was everything. I’m sure it was hard for some of them to come, knowing what they were facing, but they came because it mattered.

This past week, I’ve been in a couple of conversations with people who were concerned that they might do or say the wrong thing in response to someone’s hard story. “What if I offend them? What if they think I’m trying to fix them? What if they think I’m insensitive? What if I’m guilty of emotional colonization?” Some of these people admitted that they sometimes avoid showing up for people in grief or struggle because they simply don’t have a clue how to support them.

There are lots of “wrong” things to do in the face of grief – fixing, judging, projecting, or deflecting. Holding someone else’s pain is not easy work.

In her raw and beautiful new book, Love Warrior, Glennon Melton Doyle talks about how hard it was to share the story of her husband’s infidelity and their resulting marriage breakdown. There are six kinds of people who responded.

- The Shover is the one who “listens with nervousness and then hurriedly explains that ‘everything happens for a reason,’ or ‘it’s darkest before the dawn,’ or ‘God has a plan for you.’”

- The Comparer is the person “nods while ‘listening’, as if my pain confirms something she already knows. When I finish she clucks her tongue, shakes her head, and respond with her own story.”

- The Fixer “is certain that my situation is a question and she knows the answer. All I need is her resources and wisdom and I’ll be able to fix everything.”

- The Reporter “seems far too curious about the details of the shattering… She is not receiving my story, she is collecting it. I learn later that she passes on the breaking news almost immediately, usually with a worry or prayer disclaimer.”

- The Victims are the people who “write to say they’ve hear my news secondhand and they are hurt I haven’t told them personally. They thought we were closer than that.

- And finally, there are “the God Reps. They believe they know what God wants for me and they ‘feel led’ by God to ‘share.’”

These are all people who may mean well, but are afraid to hold space. They are afraid to be in a position where they might not know the answer and will have to be uncomfortable for awhile. Wrapped up in their response is not their concern for the other person but their concern for their own ego, their own comfort, and their own pride.

It’s easy to look at a list like that and think “Well, no matter what I do, I’ll probably do the wrong thing so I might as well not try.” But that’s a cop-out. If the person living through the hard story is worth anything to you, then you have to at least show up and try.

From my many experiences being the recipient of support when I walked through hard stories, this is my simple suggestion for what to do:

Be fully present.

Don’t worry so much about what you’ll say. Yes, you might say the wrong thing, but if the friendship is solid enough, the person will forgive you for your blunder. If you don’t even show up, on the other hand, that forgiveness will be harder to come by.

So show up. Be there in whatever way you can and in whatever way the relationship merits – a phone call, a visit, a text message.

Just be there, even if you falter, stumble, or make mistakes. And when you’re there, be FULLY present. Pay attention to what the person is sharing with you and what they may be asking of you. Don’t just listen well enough so that you can formulate your response, listen well enough that you risk being altered by the story. Dare to enter into the grit of the story with them. Ask the kind of questions that show interest and compassion rather than judgement or a desire to fix. Risk making yourself uncomfortable. Take a chance that the story will take you so far out of your comfort zone that you won’t have a clue how to respond.

And when you are fully present, your intuition will begin to whisper in your ear about the right things to do or say. You’ll hear the longing in your friend’s voice, for example, and you’ll find a way to show up for that longing. In the nuances of their story, and in the whisperings they’ll be able to utter because they see in you someone they can trust, you’ll recognize the little gifts that they’ll be able to receive.

It is only when you dare to be uncomfortable that you can hold liminal space for another person.

This is not easy work and it’s not simple. It’s gritty and a little dangerous. It asks a lot of us and it takes us into hard places. But it’s worth it and it’s really, really important.

There’s a term for the kind of thing that people do when they’re trying to fix you, rush you to a resolution, or pressure you to have positive thoughts rather than fully experiencing the grief. It’s called “spiritual bypassing”, a term coined by John Welwood. “I noticed a widespread tendency to use spiritual ideas and practices to sidestep or avoid facing unresolved emotional issues, psychological wounds, and unfinished developmental tasks,” he says. “When we are spiritually bypassing, we often use the goal of awakening or liberation to rationalize what I call premature transcendence: trying to rise above the raw and messy side of our humanness before we have fully faced and made peace with it. And then we tend to use absolute truth to disparage or dismiss relative human needs, feelings, psychological problems, relational difficulties, and developmental deficits. I see this as an “occupational hazard” of the spiritual path, in that spirituality does involve a vision of going beyond our current karmic situation.”

When we’re too uncomfortable to hold space for another person’s pain, we push them into this kind of spiritual bypassing, not because we believe it’s best for them, but because anything else is too uncomfortable for us. But spiritual bypassing only stuffs the wound further down so that it pops up later in addiction, rage, unhealthy behaviour, and physical or mental illness.

Instead of pushing people to bypass the pain, we have to slow down, dare to be uncomfortable, and allow the person to find their own path through.

There’s a good chance that the person doesn’t want your perfect response – they want your PRESENCE. They want to know that they are supported. They want a container in which they can safely break apart. They want to know you won’t abandon them. They want to know that you will listen. They want to know that they are worth enough to you that you’ll give up your own comfort to be in the trenches with them.

Your faltering attempts at being present are better than your perfect absence.

My memory of that evening in the hospital room with my son Matthew is full of redemption and beauty and grace because it was full of people who love me. None of them knew the right things to say in the face of my pain, but they were there. They listened to me share my birthing story, even though there was no resolution, and they looked into the face of my son even though they couldn’t fix him.

Nothing was more important to me than that.

********

A note about what’s coming…

A new online writing course… If you want to write to heal, to grow, or to change the world, consider joining me for Open Heart, Moving Pen, October 1-21, 2016.

An emerging coaching/facilitation program… As I’ve mentioned before, I’m currently writing a book about what it means to hold space. While writing the first three chapters, I began to dream about what else might grow out of this work and I came up with a beautiful idea that I’m very excited about. I’ll be creating a “liminal space coaching/facilitation program” that will provide training for anyone who wants to deepen their work in holding liminal space. When I started dreaming of this, I realized that I’ve been creating the tools for such a program for several years now – Mandala Discovery, The Spiral Path, Pathfinder, 50 Questions, and Openhearted Writing. Participants of the coaching/facilitation program (which will begin in early 2017) will have access to all of these tools to use in their own work, whether that’s as coaches, facilitators, pastors, spiritual directors, hospice workers, or teachers.

If the coaching/facilitation program interests you, you might want to get a head start in working through one or more of those programs so that you’ve done some of the foundational work first. The more personal work you’ve done in holding space for yourself first, the more effective you’ll be in the work. (Participants in any of those courses will be given a discount on the registration cost of the coaching/facilitation program.)

*******

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my bi-weekly reflections.

by Heather Plett | Sep 13, 2016 | grace, growth, holding space, journey, Uncategorized

I am going down to the bone. A deep cleanse, a stripping away – like a diamond cutter chipping away the grit to reveal the sparkle.

This week, there was a large dumpster parked in front of my house. In went the old couches whose springs no longer held their shape. Then the detritus collected in our garage over the eighteen years we’ve lived here. Broken broom handles, kept just in case there might be a use for them some day. Bent tools, old bicycle tires, empty cardboard boxes. Next came the branches I’d trimmed from the shrubs and trees in the Spring, a broken bench, a rusted table from the backyard, and old playground toys long abandoned by grown children.

This week, there was a large dumpster parked in front of my house. In went the old couches whose springs no longer held their shape. Then the detritus collected in our garage over the eighteen years we’ve lived here. Broken broom handles, kept just in case there might be a use for them some day. Bent tools, old bicycle tires, empty cardboard boxes. Next came the branches I’d trimmed from the shrubs and trees in the Spring, a broken bench, a rusted table from the backyard, and old playground toys long abandoned by grown children.

Finally, I stripped the floors in two-thirds of the house and dragged those out onto the growing heap in the dumpster. Each room took a little more effort than the last and each increased effort caused a little more wear and tear on my body. First I pulled out the stained carpet in the living room and hallway, the padding underneath, and the strips of upside-down nails at the edge that held it in place. Then the warped cork floor came out of the bathroom.

The kitchen, with its subfloor and multiple layers of linoleum increased the challenge, but I was up for it. After watching DIY Youtube videos, I set the circular saw at the right depth, put on safety goggles, and cut it into pieces. Then came the prying, the jockeying of appliances, and the endless nail removal.

The kitchen, with its subfloor and multiple layers of linoleum increased the challenge, but I was up for it. After watching DIY Youtube videos, I set the circular saw at the right depth, put on safety goggles, and cut it into pieces. Then came the prying, the jockeying of appliances, and the endless nail removal.

The entrance, with parquet wood glued solidly to the floor, is challenging me most and it’s the only room that remained uncompleted when they picked up the full dumpster yesterday.

Why have I done this all alone? Multiple reasons, I suppose. Cost is probably the first factor, but there are more. I wanted to prove to myself that I could – that I was strong enough and capable enough and stubborn enough and fierce enough. And I knew that it would be cathartic – to work out through my body some of the stuff that gets stuck in my mind. I was right on both counts – today, though my body aches, I feel strong and fierce and a little more healthy.

And there were other reasons – deeper reasons… Like the fact that I had some shame about the state of my house and didn’t want anyone to see the stains on the carpet, the layers of grit under the carpet, or the dried bits of food stuck to the floor under the fridge. Or the fact that I felt like this was my work to do – to cleanse this space of the brokenness of the past so that my daughters and I have a new foundation under our feet for the next part of our lives.

And there were other reasons – deeper reasons… Like the fact that I had some shame about the state of my house and didn’t want anyone to see the stains on the carpet, the layers of grit under the carpet, or the dried bits of food stuck to the floor under the fridge. Or the fact that I felt like this was my work to do – to cleanse this space of the brokenness of the past so that my daughters and I have a new foundation under our feet for the next part of our lives.

Eighteen years ago this month, we moved into this house with two toddlers. Since then, the floors have taken a lot of wear and tear – spilled milk, spilled wine, spilled tears, spilled blood, spilled lives. We sprayed and scrubbed and sprayed and scrubbed again, but carpets can only take so much, and eventually the stains were so deep it was hard to know the original colour of the carpet.

We didn’t change the carpet, though, because we had hopes for bigger changes. Fourteen years ago, we drew up plans to add a big new kitchen onto the side of the house. There was no point in replacing floors, we told ourselves – we might as well do it all at once. So we put it off until we had the money.

But then we started making choices that pushed the renovation plans further and further into the future. First, Marcel quit his job to go to university and be a stay-at-home dad. Then I took a pay-cut to work in non-profit instead of government. And then I took an even bigger leap (and pay-cut) and became self-employed. The money was just never abundant enough to justify a big expense like a new kitchen.

Instead, we lived with ugly floors and a cramped kitchen. Sadly, though, that changed the way we felt about our house. We put in less and less effort to keep it clean and we invited fewer and fewer people over because the house never looked the way we wanted it to look.

But the floors weren’t the real problem. Perhaps, in fact, they were simply a reflection of the deeper problem. There were stains in our marriage too, and no matter how many times we tried to scrub them out, they kept popping back up again, revealing themselves to us when the light shone through at the right angle. The stains were harder and harder to ignore, and we finally knew that, just like the floors, we had to tear apart our marriage to see whether the foundation beneath it was strong enough to warrant salvaging.

We tried to renovate – visited multiple counsellors over the course of a few years – but finally it was time to make a hard decision. The marriage was too broken to fix. It was better to release ourselves from it so that we each could find our way to growth and healing. Last October, he moved out, and I started decluttering and painting. The flooring, though, had to wait until we’d signed a separation agreement and the house belonged to me.

Now, as I wait for a contractor to install the new flooring (my DIY abilities only take me so far – it’s good to know when to call in the professionals), we walk on bare wooden floors in empty rooms. Our voices echo against the walls in all of this hard space.

It’s all been stripped to the bone – myself, my house, and my marriage.

Unlike the marriage, the foundation of the house is still sturdy and strong. Only a few places need attention – where it squeaks, new screws will be applied. Soon it will be built upon to create a safe and comfortable home for the family that lives here now – my daughters and me. We’ll begin to fill it with laughter again, and when there are couches with sturdy springs, we’ll welcome friends to sit with us and hear our stories. And when we spill, we’ll mop up the spills and carry on.

We had to let go of dreams along the way – the new kitchen never materialized and the family isn’t the shape we thought it would always be – but we are sturdy enough to survive and resilient enough to adjust and grow new dreams. Despite the dismantling of the marriage, our family still has a solid enough foundation to hold us.

My own foundation is strong too. In fact, it feels stronger than ever. All of this chipping away is bringing me closer and closer to my essence, to the diamond under the grit. I’ve cleared out what didn’t serve me anymore, I’ve put some new screws in place to fix whatever squeaked, and I’ve called in professionals when that seemed wise. I feel fresh and alive and ready to hold space for whatever wants to unfold next in my life.

The liminal space has been hard and painful and I still ache from the effort it’s taken. Some of the tearing away revealed grit and shadow I didn’t want anyone to see, not even myself. But in the end, there is grace and the light is shining through and it is all worth it.

****

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my bi-weekly reflections.

by Heather Plett | Sep 5, 2016 | journey

Sometimes, when you’ve read too many deep thinkers and thought too many deep thoughts, you just have to go back to Dr. Seuss for some clarity. While writing the first three chapters of my book on holding space in the last few weeks, I was puzzling over how to describe liminal space. I finally went back to this…

You can get so confused

that you’ll start in to race

down long wiggled roads at a break-necking pace

and grind on for miles cross weirdish wild space,

headed, I fear, toward a most useless place.

The Waiting Place…

…for people just waiting.

Waiting for a train to go

or a bus to come, or a plane to go

or the mail to come, or the rain to go

or the phone to ring, or the snow to snow

or waiting around for a Yes or No

or waiting for their hair to grow.

Everyone is just waiting.

In the first chapter of the book, I wrote about the liminal space we were in when we were expecting Mom’s death (an expansion of the blog post that was the catalyst for this book). Mom was in that liminal space herself (not quite dead, but no longer quite alive) and we were in that space with her) not quite bereaved and yet no longer able to participate in full relationship with her).

Inspired by Dr. Seuss, I wrote my own version…

We were waiting.

Waiting for her breath to change

or the pain to come

or the song to end

or the light to change

or the birds to visit

or the night to come

or the nurse to say “it’s almost over”.

Just waiting.

Ironically, (or perhaps serendipitously), while I’ve been writing these chapters, I’ve been in another kind of Waiting Place. This time, I am “not quite divorced and yet no longer in a marriage”. It’s been a summer of waiting. Waiting for divorce lawyers to draw up separation papers, waiting for the bank to clear the mortgage, waiting for the real estate lawyer to draw up new papers for the house, waiting for the land transfer title to go through so that I own the house. Each waiting period has been compounded with at least one of the parties involved going on vacation, so what should have taken a few weeks has dragged on for six months.

Last winter, I decluttered and repainted the interior of my house. Anticipating the new flooring that we badly need, I moved all of the living room furniture into the garage before painting. But then it took months longer than I expected to push all of the paperwork through, so the floors still aren’t finished and the furniture is still in the garage. My living room, quite literally, feels like The Waiting Place. (In fact, a friend dropped in to pick something up and thought she had the wrong place because it looked like we’d moved out.) “Waiting for the bank to call. Waiting for the lawyer to return from a month-long vacation. Waiting for the old carpet to be torn out. Waiting for the furniture to be moved back in. Everyone is just waiting.”

It’s been frustrating and what little patience I had at the beginning of the summer has been stretched to the limit. A person can only take so much of The Waiting Place. It’s been wreaking havoc with my emotions, bringing up old fears and frustration, and getting in the way of my most important relationships.

Finally, today, I decided it was time to do what I tell my coaching clients to do when they’re in the liminal space between what was and what is yet to come – stay present for what’s right now, find the tools and practices that help with processing, and open myself to what wants to emerge out of the liminal space.

For the first time in a long time, I took out my mandala journal and created a new mandala for the liminal space. It helped. Here’s a mandala journal prompt that I created out of my own process…

Liminal Space – a mandala journal prompt

In anthropology, a liminal space is a threshold. It’s an ambiguous space in the middle stage of rituals, when participants no longer hold their pre-ritual status but have not yet begun the transition to the status they will hold when the ritual is complete. That liminal space finds us between who we once were and who we are becoming. It’s disorienting, uncomfortable, and it almost always takes far longer than we expect.

Much like The Waiting Place in “Oh The Places You’ll Go“, it feels like “a most useless place”, but it’s not. It’s a time of hibernation, a time of transformation, a time of resting, and a time of deep learning.

Nobody teaches us more about liminal space than the lowly caterpillar. Not knowing why, and not having the capacity to imagine its future as a butterfly, a caterpillar knows only that it must surrender, shed its skin, create the shell of a chrysalis, and then dissolve into a formless, gel-like substance awaiting rebirth.

The liminal space is about surrender. It’s about releasing the caterpillar identity before we have the vision for the butterfly. It’s about falling apart so that we can rebuild. It’s about daring to go into the darkness so that we can, one day, emerge into the light. It’s about trusting Spirit to direct the transformation.

One of the most critical things that the caterpillar teaches us in its transformation is that we need the shell of the chrysalis to hold space for us when we fall apart.

We need a protective shell that holds us in our formless state. It keeps us safe in the midst of transformation. It protects us from outside elements so that we can focus on the important internal work we need to do. It believes in the possibility for us even before we have the capacity to believe it ourselves.

When we enter our own chrysalis, whether that is the waiting place of divorce, grief, pregnancy, job loss, career change, graduation, children moving away, or any number of human experiences, we must build our own chrysalises that hold the space for our transformation. Like a patchwork quilt, we stitch together the people or groups who hold space for us (family, friends, pastors, therapists, coaches, churches, sharing circles, etc.), the practices that help us hold space for ourselves (journaling, artwork, prayer, body work, meditation, etc.), and the spaces which make us feel safe for transformation (our home, the park, a church, etc.)

Mandala Prompt

1. Draw a large circle and a second slightly smaller circle inside it.

1. Draw a large circle and a second slightly smaller circle inside it.

2. At the centre of the mandala, glue or draw an image or words that represent the liminal space. (I used an image from The Waiting Place in “Oh, the Places You’ll Go”. Another idea might be an image of a chrysalis.)

3. In the space between the image and the next largest circle, write sentences, words, or phrases that represent what The Waiting Place is like. Explore your emotions, fears, resistance, etc., and also explore your wishes, your opportunities for learning, etc. You can use the following as prompts for starting your sentences:

– I feel…

– I am…

– I fear…

– I want…

– I will…

– I am learning…

– I wish…

(Note: I blurred mine in the image above, since it was a little too personal to share.)

4. Imagine that the outer rim (between the two outer circles) is your chrysalis. Inside the rim, write down all of the people who hold space for you, all of the practices that help you hold space, and all of the places you go when you need to hold space for yourself.

5. Colour/decorate your mandala however you wish. As you are doing so, set an intention for what you wish to invite in as you surrender to the chrysalis. For example, I whispered an intention for more patience and grace as I wait for the next story to emerge.

Want more prompts like this? Sign up for Mandala Discovery and you’ll receive 30 prompts on topics such as grief, fear, play, grace, community, etc.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my bi-weekly reflections.

This week, there was a large dumpster parked in front of my house. In went the old couches whose springs no longer held their shape. Then the detritus collected in our garage over the eighteen years we’ve lived here. Broken broom handles, kept just in case there might be a use for them some day. Bent tools, old bicycle tires, empty cardboard boxes. Next came the branches I’d trimmed from the shrubs and trees in the Spring, a broken bench, a rusted table from the backyard, and old playground toys long abandoned by grown children.

This week, there was a large dumpster parked in front of my house. In went the old couches whose springs no longer held their shape. Then the detritus collected in our garage over the eighteen years we’ve lived here. Broken broom handles, kept just in case there might be a use for them some day. Bent tools, old bicycle tires, empty cardboard boxes. Next came the branches I’d trimmed from the shrubs and trees in the Spring, a broken bench, a rusted table from the backyard, and old playground toys long abandoned by grown children. The kitchen, with its subfloor and multiple layers of linoleum increased the challenge, but I was up for it. After watching DIY Youtube videos, I set the circular saw at the right depth, put on safety goggles, and cut it into pieces. Then came the prying, the jockeying of appliances, and the endless nail removal.

The kitchen, with its subfloor and multiple layers of linoleum increased the challenge, but I was up for it. After watching DIY Youtube videos, I set the circular saw at the right depth, put on safety goggles, and cut it into pieces. Then came the prying, the jockeying of appliances, and the endless nail removal.

1. Draw a large circle and a second slightly smaller circle inside it.

1. Draw a large circle and a second slightly smaller circle inside it.