by Heather Plett | Jan 1, 2018 | change, growth, holding space

Yesterday, on the last day of 2017, I was encouraging my teenage daughter to clean her room. (If you asked for her version of the story, she might use the word “nagging”, but I’m the one telling this story, so let’s stick with “encouraging”.) She had been avoiding it for the better part of the day, despite repeated “encouragement”.

Yesterday, on the last day of 2017, I was encouraging my teenage daughter to clean her room. (If you asked for her version of the story, she might use the word “nagging”, but I’m the one telling this story, so let’s stick with “encouraging”.) She had been avoiding it for the better part of the day, despite repeated “encouragement”.

“I think I’ll feel more like doing it tomorrow,” she said. “You know… new year, new me?”

“So… you’re thinking that 2018 will transform you into the kind of person who keeps her bedroom clean?” I asked.

“A girl can dream.” And then we both laughed, because we both know there is no magical turning of the calendar that will transform her into a different person.

We keep hoping that will happen, though, don’t we? Even if we turn up our noses at new year’s resolutions, we create these little fantasies that “maybe THIS will be the year that I lose weight, get my finances in order, stop procrastinating, start exercising, stop self-sabotaging, pay my taxes on time, stop worrying, stop smoking, stop getting into unhealthy relationships, etc.” There’s just something about an as-yet untarnished year stretching in front of us that feels like a good opportunity for a fresh start.

But… just as my daughter already knows, at 15, that it will take more than a calendar change to motivate her to keep her room clean, we all know, deep down, that real change takes a great deal more effort and commitment.

This past week, while I was off work and taking a hiatus from social media, I had some time to think about what it takes to make meaningful change. Just like anyone else, there are areas of my life that I’d like to change. I’d like to lose weight, exercise more, keep my home more consistently clean, be more organized about my finances, etc. I ate too much over the holidays and was far too stationary, choosing the couch over the gym, and I could recognize the temptation to slip into that old familiar spiral of “I’m fat and too lazy and can’t seem to change that about myself, so I must be a bad person and therefore not worthy of love.” (I didn’t slip too far down that spiral, but could see it looming on the horizon.)

I’ve also been thinking about meaningful personal change on a broader spectrum – in those areas of our lives where we may be even more destructive (to ourselves and/or to others) such as addiction, abuse, etc. In this wave of accusations of sexual misconduct that’s resulted from the #metoo movement, for example, we’re discovering more and more men who’ve been guilty of deviant, destructive behaviour. Some have apologized and promised to do better in the future, but I can’t help but wonder… will they really change, or will they simply take their destructive behaviour further underground? Isn’t “getting caught” as ineffective a means of impacting meaningful change as the turning of the calendar? The high rate of recidivism in our prisons would suggest that getting caught and being punished rarely results in real change.

So what DOES result in meaningful behaviour change? How does a person become more healthy or less destructive to themselves and/or another person?

I haven’t found a magic cure, like a calendar change (if I had, I’d be 50 pounds lighter), but I do believe that these are some of the contributing factors to meaningful behaviour change:

1. Start with self-compassion and self-acceptance. This I know to be true… self-loathing and shame are never effective motivators for meaningful change. If you hate yourself and you’re wallowing in the shame of your unhealthy or destructive behaviour, you’ll keep behaving in the same way because you’ll believe that you’re incapable of anything better. You may, subconsciously, want to destroy yourself because of your perceived lack of worthiness, and you may even believe that you deserve to get caught and be punished.

It’s a vicious cycle – when I overeat, for example, I feel badly about myself. When I feel badly about myself, I don’t think I’m worthy of anything better and I want to bury the shame, so I eat some more. I have to break that cycle and it starts with extending love to myself so that I can begin to believe in my own capacity to do better. That requires that I first love myself unconditionally, EXACTLY as I am RIGHT NOW, at the weight I currently am, with the flaws I currently have. And it means committing to that kind of unconditional love EVEN IF I never make the change I’m longing for.

How do I do that? By committing to it on a daily basis, by extending kindness to myself whenever I can, by looking at myself in the mirror when I can and not flinching, by changing my self-talk from “I am useless” to “I am worthy”, and by forgiving myself over and over again when I slip up, and by not blocking the intense feelings (ie. grief, fear, shame, etc.) when they threaten to overwhelm me.

In the book The Mindful Path to Self-Compassion, Christopher Germer says “Change comes naturally when we open ourselves up to emotional pain with uncommon kindness. Instead of blaming, criticizing, and trying to fix ourselves (or someone else, or the whole world) when things go wrong and we feel bad, we can start with self-acceptance. Compassion first! This simple shift can make a tremendous difference in your life.”

2. Go deeper. A negative behaviour is never just a behaviour – it’s a mask for hidden shame, it’s a way to get a need met, it’s a response to past trauma, and/or it’s a way to avoid pain. If you can’t figure out why you can’t let go of an unhealthy pattern, it’s likely because that pattern is deeply rooted in your past pain, shame, trauma, grief, etc. It’s quite possible, that you developed that particular behaviour as a coping mechanism and there’s a subconscious part of your brain and/or body that believes that if you let go of the behaviour, you’ll be inviting back the pain or you will no longer be protecting yourself from danger. I have considered, for example, that the extra weight I carry may be my body’s way of protecting me from the kind of sexual trauma I’ve suffered in the past.

Unless you work to heal the wound that the behaviour is masking or protecting (and it may be multiple wounds rather than a single source), it will be next to impossible to make sustainable change to that behaviour. You might change the behaviour for awhile, but there’s a very good chance it will return or another destructive behaviour will move in to take its place. Our wounds have a way of getting our attention, one way or another, until we peel away the bandages and expose them to the air. I suspect, for example that many of the perpetrators of sexual abuse that we’re hearing about in the news have been victims of some kind of trauma in the past and their unhealthy use of power and their sexual deviance is really an unhealthy cry for help.

Healing of these wounds may require the support of professionals – therapists, counsellors, body workers, grief coaches, etc. Don’t be afraid to ask for help if you need it.

3. Recognize the forces at play beyond yourself. In much of modern day self-help literature, there is an underlying belief that you, and you alone, are in control of your own life. “You make your own choices, your thoughts control your outcome, you attract what shows up in your life, etc.” While there is some truth to these beliefs, they are all only partly true.

You are a product of your environment. You have been socially conditioned by the culture and system that you grew up in. You have a fore-ordained place in the social hierarchy that exists, and no matter how much you resist it, you will always be impacted by it. Your value in society is, at least in part, determined by your social status. If you are disabled, for example, you lack some of the privileges that non-disabled people enjoy. If you are a person of colour or transgender, you will likely suffer the effects of oppression and bias that others never face.

These factors limit our ability to make meaningful change in a number of ways. For one thing, a person with limited financial resources, or someone who lives in a rural location, may not have access to therapists or healthy food options or social support networks. A person who’s been ostracized for their gender or skin colour may have a harder time accessing the kind of help they need.

For another thing, there is often internalized oppression at play, even when no external force is limiting us.

A person of colour who’s grown up in a white supremacist culture will have received so many messages that they are less worthy than a white person that those messages will persist in their internal narrative. A woman who’s grown up in a patriarchal system might be a die-hard feminist, but still carry the residual shame of being a woman that she’s always been taught. Recently, while choosing a Netflix movie to watch, I realized that, though I have been overweight most of my life and believe that I am unbiased toward overweight people, I had a hard time believing that a movie with an overweight lead actor would be as good as one with a thin person. I still have internalized oppression toward fat people that’s been conditioned in me over fifty years of viewing the thin ideal on TV screens and fashion magazines.

This kind of internalized oppression makes self-compassion exponentially more difficult and therefore leaves meaningful behaviour change even more out of reach. Fifty years of internalized belief (that’s backed up by society’s standards) that fat people have less value is a pretty big boulder to push out of the way, especially when it’s complicated by the wounds that have been inflicted on this overweight body.

What can we do about this? We can educate ourselves about what forces are at play beyond us, we can choose, little by little, to release and challenge the shame and oppression inflicted on us, we can be kinder to ourselves and others who’ve suffered, and we can choose to contribute to a more just world. This knowledge does not excuse us of personal responsibility, but it does help us to be more self-compassionate when we recognize the additional burden we carry.

4. Make connections. Social isolation is one of the most significant contributors to unhealthy, destructive behaviour, whether it’s addiction, abuse, or simply poor choices. According to this article in Psychology Today, the opposite of addiction is not sobriety, it’s connection. Addiction, the writer says, is not a substance disorder, it’s a personal disorder.

Canadian psychologist Brian Alexander discovered that rats that were placed in large cages with other rats, where there were hamster wheels and multi-colored balls to play with, plenty of tasty food to eat, and spaces for mating and raising litters, were much less likely to develop an addiction to heroin than those rats living in isolated cages. Given a choice between pure water and heroin-infused water, those in isolation quickly became addicted to the heroin, while those living in community ignored it. Even rats who’d previously been isolated and sucking on the heroin water left it alone once they were introduced to communal living.

Humans are much the same – those who have families and/or support support networks are much less likely to become addicts than those who are isolated. We are social creatures – our relationships help us cope, help us heal, and help us make good choices.

Healthy relationships are those in which we can fail and still be loved, we can speak of our shame and not have more heaped upon us, we can change without being held back by their fear, and we can learn to trust even if our trust has been broken in the past. In healthy relationships, our stories matter and we are not judged for the colour of our skin, the sizes of our waists, or the limitations of our disabilities. Healthy relationships allow us to be our best selves and forgive us for being our worst selves.

In an interview on CBC radio, Alan Jacobs, the author of How to Think: A Survival Guide for a World at Odds, talked about the value of amplifying constructive voices. “If we can just stop amplifying the worst voices in society, and instead, try to promote the more constructive voices, it really would make a difference,” Jacobs suggested. He goes on to suggest “looking for people who are like-hearted, not necessarily like-minded – people who you don’t always agree with but hold the same virtues like generosity, charity, and honesty.”

These healthy, constructive relationships may be difficult to find, especially if you are already mired in shame and self-loathing, but they are not impossible. You can start by taking a course in something that interests you to find people with similar interests, or join a group on meetup.com. If you happen to be in my city, you’re welcome to join our women’s circle – we meet twice-monthly for a sharing circle where nobody is judged, no advice is offered, and friendship is freely offered.

5. Find spiritual/creative practices that support your intentions. Any time I’ve made a meaningful change in my life, and/or done deep healing work that contributes to the behaviour change, it has been supported by some form of spiritual/creative practice, whether it is a mandala journal practice, a journal practice (that might be supported by something like my 50 Questions), a labyrinth practice (ie. The Spiral Path), a body practice, a mindfulness practice, or an art practice. I recently participated in an online photographic self-expression (ie. creative selfies – offered by Amy Walsh of the Bureau of Tactical Imagination) course that surprised me with some of the ways it healed past wounds.

It seems each time I uncover something new that needs healing or changing, I find a different practice to support it. Different personal growth work seems to respond to different practices. I’ve signed up for two art-related courses for early 2018 because I know that the more time I spend in creativity, the more healthy I am in body and mind. There is something about engaging the creative part of my brain that unlocks a deeper part of me and heals what’s been hidden in the past. I also have an intention to find a body practice that works for me (once my injured shoulder heals).

One of my favourite journal practices is to have conversations with myself and to write those out as dialogue on the page. It might be a conversation between my current self and my younger self that helps uncover an unhealed wound or an unmet need. Or it might be a conversation with my fear to discover what message the fear is trying send me. Or it might be a conversation with my future self that helps my desires and longings to come to the surface. Feel free to experiment with this in your own journal – you might be surprised by what comes to the surface.

6. Take small steps and start fresh each day. “How do you eat an elephant?” asks the familiar proverb. “One bite at a time.” Don’t overwhelm yourself with unrealistic goals that may doom you for failure before you’ve even begun. Instead, set small, manageable intentions. And when you fail to meet those expectations, forgive yourself and start again.

Decide, for example, that “just for today, I will make healthy choices.” And then when you wake up the next morning, set the same goal again. And again. And again. A day of healthy choices is much more attainable than a life-long change. It’s also less to forgive if you’re simply forgiving yourself for failing today rather than for being a life-long failure.

Yes, meaningful change is possible, but remember that it may also not be necessary. Ask yourself if the change you’re seeking is genuinely what you want, or is, instead, the result of cultural norms imposed on you. Perhaps, instead of setting an unrealistic goal to become a new you, your only goal should be to practice self-compassion and acceptance of yourself just the way you are. Maybe it’s the norms of society that need to be changed rather than you?

Perhaps the most radical change you can make is to believe that you are doing the best that you can with the hand you’ve been dealt and that that’s good enough.

by Heather Plett | Mar 24, 2016 | change, Christianity, Easter, journey, marriage

It’s Easter, the time of year when Christians celebrate the end and the beginning, the death and the resurrection. It is also Springtime, when that which was dead awakes and is renewed.

For the past six years, Easter has taken on special significance for me. In my own life, I too celebrate death and resurrection, beginning and end.

Six years ago, my family and I traveled north to my brother’s house for some time with my family of origin. It was while we were there that we learned that my mom had cancer. It was also there that the crack in my marriage became too big to ignore.

At the end of the evening, when we were all shell-shocked with the realization we might lose mom, my husband and I got into an argument. I knew suddenly, with painful clarity, that if things didn’t change, this marriage would end. On the long drive home, I told him, in low tones so the girls in the back of the van couldn’t hear, that if things didn’t change, the marriage would be over. By the time we’d gotten home, we’d agreed that the next step would be counselling.

Something else happened that weekend before we’d gone to my brother’s place. Sitting in church on Easter morning, I had the sudden realization that the church I’d called home for the past fifteen years no longer felt like the right place for me to find community. Though I still loved the people in the congregation, changes in the church and changes in me made me feel like I didn’t fit anymore.

Monday morning, I woke with a horrible sense of dread, knowing that I was standing on the precipice of destruction. Everything was crumbling and I stood to lose the two people closest to me – both my husband and my mom – and the community that had once been my greatest support. The ground underneath my feet suddenly felt like it had turned to quicksand.

On top of that, I was in the first faltering steps of growing a businesses, and wasn’t making much money at it yet, so I had very little security of any kind.

When I look back over the five years following that fateful Easter Sunday, what I remember most is struggle and resistance. I was struggling to keep everything from falling apart and resistant to the changes I was afraid were coming. My husband and I attended repeated rounds of marriage counselling in hopes of saving our marriage. Together with my siblings, I supported Mom as she went through surgery and repeated rounds of chemo. I joined a new leadership committee at church, hoping a renewed commitment might help me feel like I fit again. And all the while I was struggling to make my business viable and to be a good mom for my teenage daughters.

One by one, all that I’d feared that Easter Sunday fell apart. Mom died a year and a half after she was diagnosed. My marriage ended and I stopped going to church. Three for three.

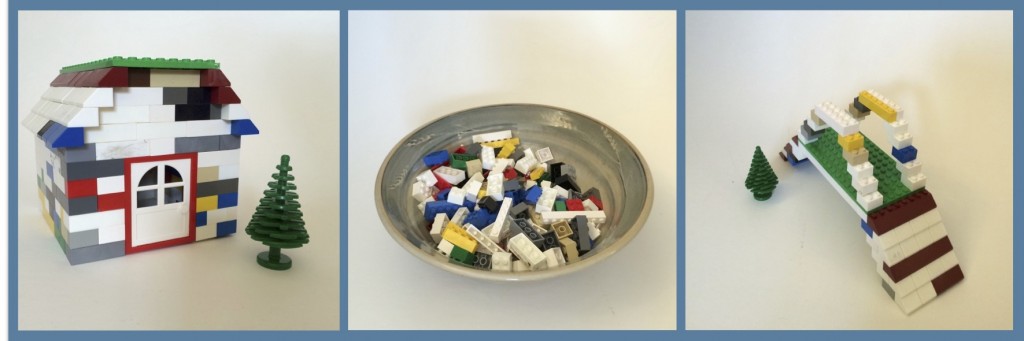

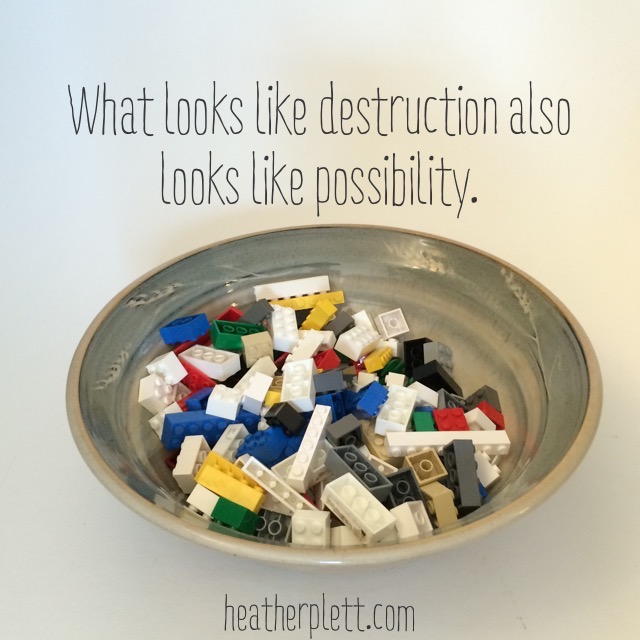

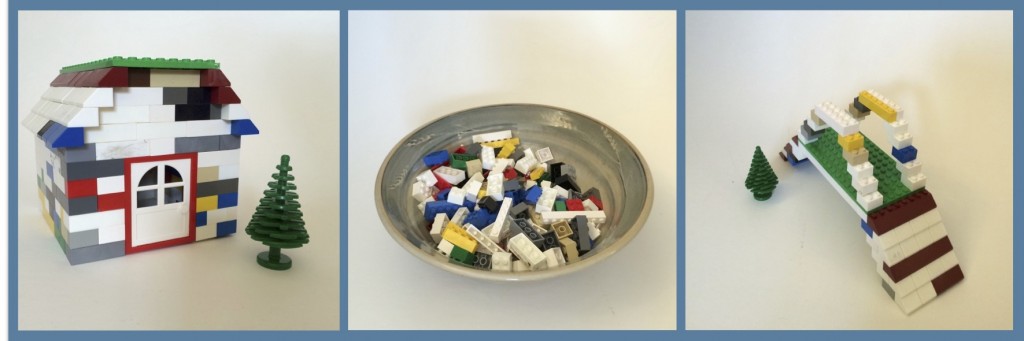

Yesterday, I was building some Powerpoint slides for a talk I’m giving in Kentucky next week, and I was looking for a visual metaphor for a point I want to make about how the work of holding space is very often the work of supporting destruction and regeneration. What I finally came up with can be seen in the photos below – a Lego house that is destroyed so that a bridge can be built out of the pieces.

As I was building it, I wasn’t focusing on how personal it felt, but now that I look at it, I see my own story. My life was like the house in the first picture – tidy and secure, with my mom, my husband, and my church standing as the walls that kept me safe. But a house wasn’t what was needed anymore. It had kept me safe and secure for the first half of my life, and for that I was grateful, but now I needed to step into a new story. Instead of the safety and security of a house, it was time to transform and embrace the possibility and risk of a bridge.

The transformation can’t happen without the destruction. That’s what the story of Easter teaches us.

What made me feel safe needed to be dismantled because it was also keeping me stuck. Safety meant that I wasn’t telling the truth. I wasn’t living authentically. I wasn’t stepping out in boldness. I was saying and doing the things I needed to say and do in order to keep everything from falling apart. I was letting fear guide me instead of courage.

But now that it’s all fallen apart and I discovered I was strong enough to live through the pain, I am receiving the gifts of the destruction.

I am living more boldly because I have less to lose. I am telling the truth because I know I can. I am living like each day matters because I know it can all end in a moment.

In the process, I am building new relationships and finding new community that feel increasingly more authentic and connected to who I am now. I don’t have time for shallowness anymore – I need depth and passion, and that’s what I’m pouring my energy and my heart into.

After the destruction, I am living a bigger, bolder, more beautiful life. I am crossing the bridge instead of staying stuck in the house. That’s the gift of falling apart.

Tomorrow is Good Friday, the day we focus on the death of Christ. It’s a sombre day that reminds us of our own endings, deaths, and failed dreams. But that’s not the end of the story. Just around the corner is Easter Sunday, the resurrection, the delight, the fulfillment.

If something is dying in your life, don’t fight it, let it go. Release it and trust, because just around the corner will be your chance to rise again, to be made new.

After the destruction comes the possibility.

* * * * *

If your life is falling apart, perhaps I can hold space for you with some coaching? If you’re rising from the ashes and are using your experience to help you hold space for others, join us in The Helpers’ Circle. If you’d like to explore how writing might support your transformation, there are two opportunities (one online and one in-person) to join the Openhearted Writing Circle.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection and my weekly reflections.

by Heather Plett | Nov 25, 2015 | Beauty, change, Community, Compassion, connection, Friendship, grace, growth

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the importance of finding your tribe – people who love you just the way you are and who cheer you on as you do courageous things.

Tribe-building is important and valuable, but it only takes you part way down the path to an openhearted life.

This week, I’ve been contemplating what we should do with the people outside of our tribes.

It’s cozy and warm inside a tribe, and the people are supportive and non-threatening, so it’s tempting to simply hide there and close off from the rest of the world. When you’re hurting, that might be the right thing to do for awhile – to protect yourself until you have healed enough to step outside of the circle.

But the problem with staying there too long is that it creates a world of “us and them”. When you stay too close to your own tribe, it becomes easier and easier to justify your own choices and opinions and more and more difficult to understand people who think differently from you. Before long, you’ve become suspicious of everyone outside of your tribe, and when their actions threaten your way of life, you do whatever it takes to protect yourself. Fear breeds in a closed-off life.

Last week, I knew it was time to challenge myself to step outside my tribe. I’d been playing it safe too much lately, so when I saw a Facebook posting for an open house at the local mosque, I decided that was a good place to start. I shared the information with friends, but chose not to bring anyone with me. Bringing friends with me into unfamiliar territory makes me less open to conversations with people who are different from me and I didn’t want that – I wanted to go in with an open, unguarded heart. That’s one of the reasons I’ve learned to love solo traveling – it’s scary at first, but it opens me to a whole world of new opportunities and friendships that don’t happen as naturally when I’m hiding behind the safety of a group.

I have traveled in predominately Muslim parts of the world and have always been warmly received, so I knew that the open house would be a pleasant experience. It turned out to be even more pleasant than I’d expected.

First there was Mariam, a young university student who served as tour guide to me and a small group of strangers. Mariam’s easy smile and warm personality made us all feel instantly comfortable. She lead us through the gym to the prayer room and told us why she’s happy that the women pray in a separate area from the men. “I want to be close to God when I pray, not distracted by who might be looking at me or bumping into me.” Before the tour was over, Mariam hugged me twice and I felt like I’d made a new friend.

First there was Mariam, a young university student who served as tour guide to me and a small group of strangers. Mariam’s easy smile and warm personality made us all feel instantly comfortable. She lead us through the gym to the prayer room and told us why she’s happy that the women pray in a separate area from the men. “I want to be close to God when I pray, not distracted by who might be looking at me or bumping into me.” Before the tour was over, Mariam hugged me twice and I felt like I’d made a new friend.

Then there was the grinning young man at the table by the sign that read “your name in Arabic”. His name now escapes me, but I can tell you he never stopped smiling through our whole conversation and was one of the friendliest young men I’ve met in a long time. He told me, while he wrote my name, that he’d learned some of his Arabic from cartoons. Growing up in Ontario, he’d preferred Arabic cartoons to Barney or Sesame Street.

At the “free henna” table, I met Saadia, who moved here from Pakistan three years ago because she and her husband wanted to give their children a better chance at a good education. Her husband is a doctor who’s still trying to cross all of the hurdles that will allow him to practice in Canada. Before our conversation was over, Saadia had given me her phone number in case I ever want to invite her to my home to give me and my friends hennas.

What struck me, as I left the mosque, was how much grace and courage it takes, when your people have become the object of racism, fear, and oppression, to open your hearts, homes, and gathering places to strangers. Instead of hiding within the safety of their own tribe and justifying their need for protection and safety from others, the local Muslim community threw their doors and hearts open wide and said “let’s be friends. We are not afraid of you – please don’t be afraid of us.”

I experienced the same grace and courage among the Indigenous people of our community last Spring after we were named the “most racist city in Canada”. Instead of retreating into the safety of their tribes, they welcomed many of us into openhearted healing circles. Instead of being angry, they taught us that reconciliation starts with forgiveness and the courage to risk friendships across tribal lines.

I will be forever grateful to Rosanna, who invited me to co-host a series of meaningful conversations with her, to Leonard who handed me a drum and welcomed me to play in honour of Mother Earth’s heartbeat, to Gramma Shingoose who gave me a stone shaped like a heart and shared the story of her healing journey after a childhood in residential school, to Brian who welcomed me into the sweat lodge, and to many others who opened their hearts and reached across the artificial divide between Indigenous and settler.

The more I’ve had the privilege of building friendships with openhearted people whose world looks different from mine, the bigger, more beautiful, and less fearful my life has become.

This week, I’ve read Gloria Steinem’s memoir, My Life on The Road and there is so much in it that resonates with the way I choose to live my life. It’s a beautiful reflection of how her life has been changed by the people she has encountered while on the road. “Taking to the road – by which I mean letting the road take you – changed who I thought I was. The road is messy in the way that real life is messy. It leads us out of denial and into reality, out of theory and into practice, out of caution and into action, out of statistics and into stories – in short, out of our heads and into our hearts. It’s right up there with life-threatening emergencies and truly mutual sex as a way of being fully alive in the present.”

Another quote speaks to how much broader her thinking has become because of her encounters on the road. “What we’ve been told about this country is way too limited by generalities, sound bites, and even the supposedly enlightened idea that there are two sides to every question. In fact, many questions have three or seven or a dozen sides. Sometimes I think the only real division into two is between people who divide everything into two and those who don’t.”

We don’t have to spend as much time traveling as Gloria Steinem does in order to live this way – we simply have to open our hearts to the people and experiences in our own communities that have the potential to stretch and change us and lead us past a life with only two sides. Sometimes a conversation with the next door neighbour is enough to help us see the world through more open eyes.

* * * * *

p.s. Would you consider supporting our fundraiser to sponsor a Syrian refugee family?

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Jul 14, 2015 | art, change, connection, Creativity

This past weekend, I made my annual pilgrimage to the Winnipeg Folk Festival. I’ve been going for 30 years and I’ll probably keep going for 30 more, because it fills me up, inspires me, and nourishes my creative spirit. Four days of great music, surrounded by tall trees, big prairie skies, and interesting people is a little like what I imagine heaven to be.

Inspired by all there is to see and hear, I always come home with a collection of jewels – little pieces of lyrics scribbled on my program, stories gathered from conversations with friends or strangers, colourful photos of the bubble man or the stilt-walkers, new cds of my latest favourite artist, and a trinket or two from the handmade village.

Everything inspires me, and when I return home, I feel like I need a week to digest it all.

Most of the quotes I pour over afterward come from the singer-songwriters. But this year’s gem comes from the artisan who made the beautiful necklace I brought home.

Ro Walton (of Windy Tree) makes one-of-a-kind jewelry from branches of the arbutus tree (which I saw plenty of when I was on Whidbey Island in May). Each one has a unique design, carved free-hand on a scroll saw.

Marveling at the intricate designs in his pieces, I remarked “you must have a steady hand.”

Ro’s response: “It’s more about having a steady mind.”

“If my mind’s not in the right place,” he continued, “I have to do other things like cutting and sanding. Only when my mind is steady can I approach the scroll saw for the intricate work.”

I’ve been thinking about that ever since. Only when we do the work of steadying our minds can we do our most intricate work.

That’s what I’m focusing on during the month of July – my own quest for a steady mind. Work-wise, Winter and Spring were a bit of a whirlwind, and then some things in my personal life got a little shaky, so I am doing my best to seek some stillness so that the really deep and intense art that wants to grow out of me can do so.

I’ll be going away next week for a few days of intense writing, trying to wrap up the book that I’ve come back to after putting it on a shelf for a couple of years. I have found that the only way I can really dive into that kind of writing is to go away and be silent, so I will do that for a few days. In between the writing, I’ll wander the beach, play with art supplies, and read good books. All of these things help me maintain the kind of steady mind that lets me write.

The necklace that I bought from Ro depicts a tree hanging from the edge of a cliff. (The tree is cut through the wood so that the design shows through on the back as well.) This is the one that appealed to me most because of the challenge and improbability of a strong and healthy tree rooting itself in such a precarious place. I imagine that far below it, the waves are crashing against the rock and above it, the storms are rolling in. In the middle of all of this chaos, the tree remains firmly rooted.

The necklace that I bought from Ro depicts a tree hanging from the edge of a cliff. (The tree is cut through the wood so that the design shows through on the back as well.) This is the one that appealed to me most because of the challenge and improbability of a strong and healthy tree rooting itself in such a precarious place. I imagine that far below it, the waves are crashing against the rock and above it, the storms are rolling in. In the middle of all of this chaos, the tree remains firmly rooted.

Somehow, the tiny seed that planted itself in the crack of a rock found enough stillness and sunlight and rainwater to grow into a strong tree. After all of the hard work it took to flourish there, that tree now offers a rare place to rest for the birds flying overhead.

This is the story I want to tell of my life – a story of rootedness and strength, despite the chaos all around me, despite the fact that sometimes I feel like I’m clinging to the edge of a cliff. This is what I want to be – a place of solace and support for those who’ve been tossed by the wind and the waves.

To live that story, I must make sure I put down strong roots and that I practice having a “steady mind” in the midst of chaos. That’s what next week is about.

I encourage you to do the same. Find a way to steady your mind, whether that means staying off social media for awhile, going on retreat to a friend’s cabin, taking long walks every morning, attending a music festival, doing yoga, or committing to some art playtime every week. And plant your roots deeply into the rock that is the God of your understanding.

Giving yourself that kind of time and nourishment is not selfish, it’s essential if you want to do your best work. Whether you are an artist, a teacher, a business owner, a hospice worker, or a stay-at-home parent, you need a steady mind, a steady heart, and a steady body. You’ll only get that when you give yourself what you need.

Then, and only then, will you be the kind of tree the birds can rest in after their long flight.

Be good to yourself this summer. Plant your roots, steady your mind, and give yourself the nourishment you need.

If you’re looking for something to nourish you, perhaps Mandala Discovery might help? It starts again in August.

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Jun 3, 2015 | change, circle, Community, Compassion, growth, journey, Leadership

“…whenever I dehumanize another, I necessarily dehumanize all that is human—including myself.”

– from the book Anatomy of Peace

This week, I’ve been thinking about how we hold space when there is an imbalance in power or privilege.

This has been a long-time inquiry for me. Though I didn’t use the same language at the time, I wrote my first blog post about how I might hold space for people I was about to meet in Africa whose socio-economic status was very different from mine.

I had long dreamed of going to Africa, but ten and a half years ago, when I was getting ready for my first trip, I was feeling nervous about it. I wasn’t nervous about snakes or bugs or uncomfortable sleeping arrangements – I was nervous about the way relationships would unfold.

I was traveling with the non-profit I worked for at the time and we were visiting some of the villages where our funding had supported hunger-related projects. That meant that, in almost every encounter I’d have, I would represent the donor and they would be the recipients. I was pretty sure that those two predetermined roles would change how we’d interact. My desire to be in authentic and reciprocal relationship with them would be hindered by their perceived need to “keep the donor happy”.

That challenge was further exacerbated by:

- a history of colonization in the countries where I was visiting, which meant that my white skin would automatically be associated with the colonizers

- my own history of growing up in a church where white missionaries often visited and told us about how they were working in Africa to convert the heathens

In that first blog post, I wrestled with what it would mean to carry that baggage with me to Africa. I ended the post with this… I won’t expect that my English words are somehow endued with greater wisdom than theirs. I will listen and let them teach me. I will open my heart to the hope and the hurt. I will tread lightly on their soil and let the colours wash over me. I will allow the journey to stretch me and I will come back larger than before.

In another blog post, after the trip, I wrote about how hard it was to find the right words to say to the people who’d gathered at a food distribution site…What can I say that is worthy of this moment? How can I assure them I long for friendship, not reverence?

That trip, and other subsequent ones to Ethiopia, India, and Bangladesh, stretched and challenged me. Each time I went, I wrestled with the way that my privilege and access to power would change my interactions. I became more and more intentional about entering into relationships with humility, grace, and openheartedness. I did my best to treat each person with dignity and respect, to learn from them, and to challenge my own assumptions and prejudice.

Nowadays, I don’t have the same travel opportunities, but I still find myself in a variety of situations in which there is imbalance. Sometimes I have been the one with less privilege and power (like when I used to work in corporate environments with male scientists, or when I traveled with and offered support to mostly male politicians). Other times, I have access to more power and/or privilege than others in the room (like when I am the teacher at the front of the classroom, or I am meeting with people of Indigenous descent). In each situation, I find myself aware of how the imbalance impacts the way we interact.

This week in Canada, the final report on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s findings related to Residential Schools has come out and it raises this question for all of us across the country. Justice Murray Sinclair, chair of the commission, has urged us to take action to address the cultural genocide of residential schools on aboriginal communities. Those are strong words (and necessary, I believe) and they call all of us to acknowledge the divide in power and privilege between the Indigenous people and those of us who are Settlers in this nation.

How do we hold space in a country in which there has been genocide? How do we who are settlers acknowledge our own privilege and the wounds inflicted by our ancestors in an effort to bring healing to us all?

This is life-long learning for me, and I don’t always get it right (as I shared after our first race relations conversation), but I keep trying because I know this is important. I know this matters, no matter which side of the power imbalance I stand on.

If we want to see real change in the world, we need to know how to be in meaningful relationships with people who stand on the other side of the power imbalance.

Here are some of my thoughts on what it takes to hold space for people when there is a power imbalance.

- Don’t pretend “we’re all the same”. White-washing or ignoring the imbalance in the room does not serve anyone. Acknowledging who holds the privilege and power helps open the space for more honest dialogue. If you are the person with power, say it out loud and do your best to share that power. Listen more than you speak, for example, or decide that any decisions that need to be made will be made collectively. If you lack power, say that too, in as gracious and non-blaming a way as possible.

- Change the physical space. It may seem like a small thing to move the chairs, to step away from the podium, or to step out from behind a desk, but it can make a big difference. A conversation in circle, where each person is at the same level, is very different from one in which a person is at the front of the room and others are in rows looking up at that person. In physical space that suggests equality, people are more inclined to open up.

- Invite contribution from everyone. Giving each person a voice (by using a talking piece when you’re sharing stories, for example) goes a long way to acknowledging their dignity and humanity. Allowing people to share their gifts (by hosting a potluck, or asking people to volunteer their organizational skills, for example) makes people feel valued and respected.

- Create safety for difficult conversations. When you enter into challenging conversations with people on different sides of a power imbalance, you open the door for anger, frustration, grief, and blaming. Using the circle to hold such conversations helps diffuse these heightened emotions. Participants are invited to pour their stories and emotions into the center instead of dumping them on whoever they choose to blame.

- Don’t pretend to know how the other person feels. Each of us has a different lived experience and the only way we can begin to understand what another person brings to the conversation (no matter what side of the imbalance they’re on) is to give them space to share their stories. Acting like you already know how they feel dismisses their emotions and will probably cause them to remain silent.

- Offer friendship rather than sympathy. If you want to build a reciprocal relationship, sympathy is the wrong place to start. Sympathy is a one-way street that broadens the power gap between you. Friendship, on the other hand, has well-worn paths in both directions. Sympathy builds power structures and walls. Friendship breaks down the walls and puts up couches and tables. Sympathy creates a divide. Friendship builds a bridge.

- Even if you have little access to power or privilege, trust that your listening and compassion can impact the outcome. I was struck by a recent story of how a group of Muslims invited anti-Muslim protestors with guns into their mosque for evening prayers. An action like that can have significant impact, cracking open the hearts of those who’ve let themselves be ruled by hatred.

- Don’t be afraid to admit that you don’t know the way through. Real change happens only when there is openness to paths that haven’t been discovered yet. If you walk into a conversation assuming you know how it needs to turn out, you won’t invite authenticity and openness into the room. Your vulnerability and openheartedness invites it in others.

- Don’t try this alone. This kind of work requires strong partnerships. People from all sides of the power or privilege divide need to not only be in the conversation, but be part of the hosting and planning teams. That’s the only way to ensure all voices are heard and all cultural sensitivities are honoured.

I welcome your thoughts on this. What have you found that makes a difference for conversations where there is an imbalance?

Interested in more articles like this? Add your name to my email list and you’ll receive a free ebook, A Path to Connection. I send out weekly newsletters and updates on my work.

by Heather Plett | Jan 28, 2015 | art of hosting, change, growth, journey, Leadership

“The success of our actions as change-makers does not depend on what we do or how we do it, but on the inner place from which we operate.” – Otto Sharmer

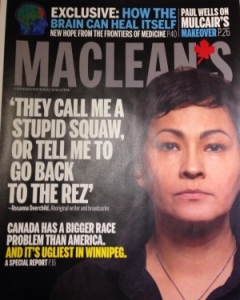

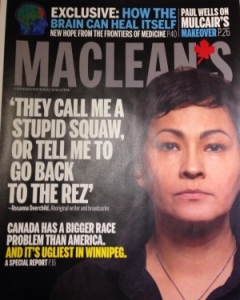

Last week, the city that I love and call home was named “the most racist city in Canada.” That hurt. It felt like someone had insulted my family.

Last week, the city that I love and call home was named “the most racist city in Canada.” That hurt. It felt like someone had insulted my family.

The article mentions many heartbreaking stories of the way that Indigenous people have been treated in our city, and while I wanted to say “but… we’re so NICE here! Really! You have to see the other side too!” I knew that there was undeniable truth I had to face and own. My family isn’t always nice. Neither is my city.

Though I work hard not to be racist, have many Indigenous friends in my circles, and am married to a Metis man, I knew that my response to the article needed to not only be a closer look at my city but a closer look at myself. I may not be overtly racist, but are there ways that I have been complicit in allowing this disease to grow around me? Are there things that I have left unsaid that have given people permission for their racism? Are there ways in which my white privilege has made me blind?

Ever since the summer, when I attended the vigil for Tina Fontaine, a young Indigenous woman whose body was found in the river, I have been feeling some restlessness around this issue. I knew that I was being nudged into some work that would help in the healing of my city and my country, but I didn’t know what that work was. I started by carrying my sadness over the murdered and missing Indigenous women into the Black Hills when I invited women on a lament journey.

Ever since the summer, when I attended the vigil for Tina Fontaine, a young Indigenous woman whose body was found in the river, I have been feeling some restlessness around this issue. I knew that I was being nudged into some work that would help in the healing of my city and my country, but I didn’t know what that work was. I started by carrying my sadness over the murdered and missing Indigenous women into the Black Hills when I invited women on a lament journey.

This week, after the Macleans article came out, our mayor made a courageous choice in how he responded to the article. In a press conference called shortly after the article spread across the internet, he didn’t get defensive, but instead he spoke with vulnerability about his own identity as a Metis man and about how his desire is for his children to be proud of both of the heritages they carry – their mother’s and his. He then invited several Indigenous leaders to speak.

There was something about the mayor’s address that galvanized me into action. I knew it was time for me to step forward and offer what I can. I sent an email and tweet to the mayor, thanking him for what he’d done and then offering my expertise in hosting meaningful conversations. Because I believe that we need to start healing this divide in our city and healing will begin when we sit and look into each others’ eyes and listen deeply to each others’ stories.

After that, I purchased the url letstalkaboutracism.com. I haven’t done anything with it yet, but I know that one of the things I need to do is to invite more people into a conversation around racism and how it wounds us all. I have no idea how to fix this, but I know how to hold space for difficult conversations, so that is what I intend to do. Circles have the capacity to hold deep healing work, and I will find a way to offer them where I can.

Since then, I have had moments of clarity about what needs to be done next, but far more moments of doubt and fear. At present, I am sitting with both the clarity and the doubt, trying to hold both and trying to be present for what wants to be born.

Here are some of the things that are showing up in my internal dialogue:

- Isn’t it a little arrogant to think I have any expertise to offer in this area? There are so many more qualified people than me.

- What if I offend the Indigenous people by offering my ideas, and become like the colonizers who think they have the answers and refuse to listen to the wisdom of the people they’re trying to help?

- There are already many people doing healing work on this issue, and many of them are already holding Indigenous circles. I have nothing unique to contribute.

- What if I host sharing circles and too much trauma and/or conflict shows up in the circle and I don’t know how to hold it?

- What if this is just my ego trying to do something “important” and get attention for me rather than the cause?

And so the conversation in my head goes back and forth. And the conversations outside of my head (with other people) aren’t much different.

At the same time as this has been going on, I have been working through the first two weeks of course material for U Lab: Transforming Business, Society and Self. In one of the course videos, Otto Sharmer talks about the four levels of listening – from downloading (where we listen to confirm habitual judgements), to factual (listening by paying attention to facts and to novel or disconfirming data), to empathic (where we listen with our hearts and not just our minds), and finally to generative (where we move with the person speaking into communion and transformaton).

As soon as I read that, I knew that whatever I do to help create space for healing in my city, it has to start with a place of deep listening – generative listening, where all those in the circle can move into communion and transformation. I also knew, as I sat with that idea, that that generative listening has to begin with me.

If I am to serve in this role, I need to be prepared to move out of my comfort zone, into generative listening with people who have been wounded by racism in our city AND with people who live with racial blindspots. AND (in the words of Otto Sharmer) I need to move out of an ego-system mentality (where I am seeking my own interest first), into a generative, eco-system mentality (where I am seeking the best interest of the community and world around me).

So that is my intention, starting this week. I already have a meeting planned with an Indigenous friend who has contributed to, and wants to teach, an adult curriculum on racism, to find out how I can support her in this work. And I will be meeting with another friend, a talented Indigenous musician, about possible partnership opportunities. And I will be a sitting in an Indigenous sharing circle, listening deeply to their stories.

I am not sharing these stories to say “look at me and all of the good things I’m doing”. That would be my ego talking, and that’s one of the things I’m trying to avoid. Instead, I’m sharing it to say “look at the complexity that a thinking woman (sometimes over-thinking woman) goes through in order to become an effective, and humble, change-maker.

That brings me back to the quote at the top of the page.

“The success of our actions as change-makers does not depend on what we do or how we do it, but on the inner place from which we operate.” – Otto Sharmer

The inner place. That is what will determine the success of our actions. I can have all the smart ideas in the world, and a big network of people to help roll them out, but if I have not done the internal work first, my success will be limited.

If I don’t do the inner work first, then my ego will run rampant and I will stomp all over the people that I say I care about. Or I will suffer from jealousy, or self doubt, or self-centredness, or vindictiveness, or all of the above.

If I don’t do the internal work and ask myself important questions about what is rooted in my ego and what is generative, then I could potentially do more harm than good.

So how do I do that internal work? Here are some of the things that I do:

1. As we say in Art of Hosting work, I host myself first. In other words, I ask of myself whatever I would ask of others I might invite into circle, I look for both my shadows and my strengths, and I do the kind of self-care I would encourage my clients to do when they find themselves in the middle of big shifts.

2. I ask myself a few pointed questions to determine whether the ego is too involved. For example, when my friend came to me to share the work she wants to do, hosting circles in the curriculum she has developed, there was a little ego-voice that spoke up and said “But wait! This was supposed to be YOUR work! If you support her, you’ll have to be in the background.” The moment I heard that voice, I had to ask myself “do you truly want to make a difference around the issue of racism or do you just want to make a name for yourself?” And: “If this is successful in impacting change, but you have only a secondary role, is it still worthwhile?” It didn’t take long for me to know that I wanted to be wholeheartedly behind her work.

3. I pause. As we learn in Theory U, the pause is the most important part – it’s where the really juicy stuff happens. The pause is where we notice patterns that we were too busy to notice before. It’s where the voice of wisdom speaks through the noise. It’s where we are more able to sink into generative listening. In Theory U, we call it “presencing” – a combination of “presence” and “sensing”. There’s a quality of mindfulness in the pause that helps me notice and experience more and be awake to receive more wisdom.

4. I do the practices that help bring me to wise thought and wise action. For me, it’s journaling, art, mandala-making, nature walks, and labyrinth walks. I never make a major decision without spending intentional time in one of those practices. Almost always, something more profound and wise shows up that I wouldn’t have considered earlier.

5. I listen. The ego doesn’t want me to seek input from other people. The ego wants to be in control and not invite partners in to share the spotlight. If I want to move out of ego-system, though, I need to spend time listening for others’ stories and wisdom. This doesn’t mean I listen to EVERYONE. Instead, I use my discretion about who are the right people to seek wise council from. I listen to those who have done their own personal work, whose own egos won’t try to trap me and keep me from succeeding, and who genuinely care about the issue I’m working on.

6. I check in with myself and then move into action when I’m ready. Although the pause, the questions, and the personal practice are all very important, the movement into action is equally important. There have been far too many times when my questions and ego have trapped me in a spiral and I’ve failed to move into action. Just thinking about it won’t impact change. I need to be prepared to act, even if I still have doubt. If I fail in that action, I can always go back and re-enter the presencing stage.

This is an ongoing story and I hope to continue sharing it as it emerges. If you, too, want to become a change-maker, then I’d love to hear from you. What are the processes you go through in order to ensure your “inner place” is healthy and your listening and actions are generative? What issues are currently calling you into action?

If this resonates with you, check out The Spiral Path, which begins February 1st. Based on the three stages of the labyrinth, (release, receive, and return), it invites you to go inward to do this internal work and then to move outward to serve in the way that you are called.

Also… we’re looking for a few more change-makers to attend Engage, a one-of-a-kind retreat that will teach you more about how to do your inner work so that you can move into generative action.

Yesterday, on the last day of 2017, I was encouraging my teenage daughter to clean her room. (If you asked for her version of the story, she might use the word “nagging”, but I’m the one telling this story, so let’s stick with “encouraging”.) She had been avoiding it for the better part of the day, despite repeated “encouragement”.

Yesterday, on the last day of 2017, I was encouraging my teenage daughter to clean her room. (If you asked for her version of the story, she might use the word “nagging”, but I’m the one telling this story, so let’s stick with “encouraging”.) She had been avoiding it for the better part of the day, despite repeated “encouragement”.

The necklace that I bought from Ro depicts a tree hanging from the edge of a cliff. (The tree is cut through the wood so that the design shows through on the back as well.) This is the one that appealed to me most because of the challenge and improbability of a strong and healthy tree rooting itself in such a precarious place. I imagine that far below it, the waves are crashing against the rock and above it, the storms are rolling in. In the middle of all of this chaos, the tree remains firmly rooted.

The necklace that I bought from Ro depicts a tree hanging from the edge of a cliff. (The tree is cut through the wood so that the design shows through on the back as well.) This is the one that appealed to me most because of the challenge and improbability of a strong and healthy tree rooting itself in such a precarious place. I imagine that far below it, the waves are crashing against the rock and above it, the storms are rolling in. In the middle of all of this chaos, the tree remains firmly rooted.