by Heather Plett | Mar 18, 2015 | art of hosting, Community, connection, grief, Martyn Joseph

Anytime we can listen to true self and give it the care it requires, we do so not only for ourselves but for the many others whose lives we touch.

– Parker Palmer, Let your Life Speak

When I shared my post about what it means to hold space for people and it went viral, I learned this…

This desire to hold space well for other people is vast and diverse.

I have heard from the most fascinating range of people about how this post is being circulated and used. It’s showing up in home schooling forums, palliative and hospice care circles, art communities, spiritual retreat centres, universities, alcoholics anonymous groups, psychotherapists’ offices, etc. The most interesting place I heard about it being shared was within the US Marines. It is also touching the lives of people supporting their parents, children, spouses and friends through difficult times.

The lesson in this is that no matter who or where you are, you can do the beautiful and important work of holding space for other people. There are so many of us who are making this a priority in our lives that I feel hopeful that this world is finally swinging like a pendulum away from a place of isolation and individualism to a place of deeper connection and love. Isn’t that a beautiful idea?

Recently, I participated in an online course on “Leading from the Future as it Emerges: From Ego-system to Eco-system” and the underlying premise of the course was that we need to find a way to make deeper connections with ourselves, others, and the earth so that we bring about a paradigm shift and stop this crash course we’re on. There were more than 25,000 from around the world participating in the course. That’s a LOT of people who share a common passion for changing the ways in which we interact and make decisions. I walked away feeling increasingly hopeful that I am part of a swelling tide of change. The response to my blog post has further reinforced that hopeful feeling.

We are doing the best we can to live in love and community.

We are not perfect, and sometimes we still make selfish decisions, but we are doing our best. Thank you for being part of the change.

The other thing that struck me as I read through all of the comments, emails, etc., is that, while all of you are all responding from a place of generosity and openheartedness, wanting to learn more about holding space for others, you also need to be given permission and encouragement to hold space for yourselves.

This is really important. If we don’t care for ourselves well in this work, we’ll suffer burnout, and risk becoming cynical and/or ineffective.

PLEASE take the time to hold space for yourself so that you can hold space for others.

It is not selfish to focus on yourself. In fact, it’s an act of generosity and commitment to make sure that you are at your best when you support others. They will get much more effective, meaningful, and openhearted support from you if you are healthy and strong.

In the Art of Hosting work that I do and teach, we talk about “hosting ourselves first”. What does it mean to “host myself first”? It means, simply, that anything I am prepared to encounter once I walk into a room, I need to be prepared to encounter and host in myself first. In order to prepare myself for conflict, frustration, ego, fear, anger, weariness, envy, injustice, etc., I need to sit with myself, look into my own heart, bear witness to what I see there, and address it in whatever way I need to before I can do it for others. I can’t hide any of that stuff in the shadows, because what is hidden there tends to come out in ways I don’t want it to when I am under stress.

AND just as I am prepared to offer compassion, understanding, forgiveness, and resolution to anything that shows up in the room, I need to offer it to myself first. Only when I am present for myself and compassionate with myself will I be prepared to host with strength and courage.

In other words, all of those points that I made about how to hold space for others can and should be applied to yourself first. Give yourself permission to trust your own intuition. Give yourself only as much information as you can handle. Don’t let anyone take your power away. Keep your ego out of it. Make yourself feel safe enough to fail. Give guidance and help to yourself with humility and thoughtfulness. Create your own container for complex emotions, fears, trauma, etc. And allow yourself to make decisions that are different from what other people would make.

This isn’t necessarily easy, when you’re doing the often stressful and time-consuming work of holding space for others, but it is imperative.

Here are some other tips on how to hold space for yourself.

- Learn when to walk away. You can’t serve other people well when your energy is depleted. Even if you can only leave the hospital room of your loved one for short periods of time, or you’re a single mom who doesn’t have much of a support system for caring from your kids, it is imperative that you find times when you can walk away from the place where you are needed most to take deep breaths, walk in nature, go for a swim, or simply sit and stare at the sunset. Replenish yourself so that you can return without bitterness. Whenever you can, take a longer break (a week at a retreat does wonders).

- Let the tears flow. When the only thing you can do is cry, that’s often the best thing you can do. Let the tears wash away the accumulated ick in your soul. A social worker once told me that “tears are the window-washer of the soul” and she was right. They help to clear your vision so that you can see better and move forward more successfully. When my husband was in the psych ward a few years ago, and I still had to maintain some semblance of normalcy for my children, I spent many, many hours weeping as I drove from the hospital to the soccer field and back again. Releasing those tears when I was alone or with close friends allowed me to be strong for the people who needed me most.

- Let others hold space for you. You can’t do this work alone and you’re not meant to. We are all meant to be communal people, showing up for each other in reciprocal ways. As I mentioned in my original post about holding space, we were able to hold space for my mom in her dying because others (like Anne, the palliative care nurse) were holding space for us. Many others were stopping to visit, bringing food, etc. We would have been much less able to walk that path with Mom if we hadn’t known there was a strong container in which we were being held.

- Practice mindfulness. Mindfulness is simply “paying attention to your attention”. In mindfulness meditation, you are taught that, instead of trying to stop the thoughts, you should simply notice them and let them pass. You don’t need to sit on a meditation cushion to practice mindfulness – simply pay attention to what emotions and thoughts are showing up, and when they come, wish them well and send them on their way. Are you angry? Notice the anger, name it anger, ask yourself whether there is any value in holding onto this anger, and then let it pass. Frustrated? Notice, name, inquire, and then let it pass.

- Find sources of inspiration. There are many, many writers, artists, musicians, etc. whose wisdom can help you hold space for yourself. When I was nearing a nervous breakdown earlier this week because of the intensity of my post going viral, I went to a Martyn Joseph concert (my favourite musician), and when he started to sing “I need you brave, I want you brave, I need you strong to sing along, You are so beautiful, and I’m not wrong”, I was sure he was singing directly to me. (Watch it on Youtube.) That evening of music shifted the way I felt about what was going on and I was able to walk back into my work with courage and strength. Later in the week, when my site crashed and I was having trouble bringing it back to life, I went to sit in the poetry section of my favourite bookstore and read Billy Collins.

- Let other people live their own stories. You are not in charge of the world. You are only in charge of yourself and your own behaviours, thoughts, emotions, etc. Often when you are a caregiver, you’ll find yourself the target of other people’s frustration, anger, fear, etc. REMEMBER – that’s THEIR story, not yours. Just because they yell at you doesn’t mean you’re doing it wrong. Take a deep breath, say to yourself “I am not responsible for their emotion, I am only responsible for how I respond”, and then let it go. When you’re feeling wounded by what they’re projecting on you, return to the points above and walk away, practice mindfulness, and let others hold space for you.

- Find a creative outlet for processing what you’re experiencing. Write in a journal, paint, dance, bake, play the guitar – do whatever replenishes your soul. Few things are as healing as time spent in creative practice. One of my favourite things to do is something I call Mandala Journailing, where I bring both my words and my wordlessness to the circle. You can learn to do it yourself in Mandala Discovery: 30 days of self-discovery through mandala journaling (which starts April 1st).

I hope that you will find the time this week to hold space for yourself. Your work is important, and the world needs more generous and open hearts who are healthy and strong enough to serve well.

Blessings to you.

Interested in more articles like this? Join our new community at atenderspace.substack.com

by Heather Plett | Mar 11, 2015 | art of hosting, circle, Community, Compassion, grace, grief, journey, leadership, Uncategorized

When my mom was dying, my siblings and I gathered to be with her in her final days. None of us knew anything about supporting someone in her transition out of this life into the next, but we were pretty sure we wanted to keep her at home, so we did.

While we supported mom, we were, in turn, supported by a gifted palliative care nurse, Ann, who came every few days to care for mom and to talk to us about what we could expect in the coming days. She taught us how to inject Mom with morphine when she became restless, she offered to do the difficult tasks (like giving Mom a bath), and she gave us only as much information as we needed about what to do with Mom’s body after her spirit had passed.

“Take your time,” she said. “You don’t need to call the funeral home until you’re ready. Gather the people who will want to say their final farewells. Sit with your mom as long as you need to. When you’re ready, call and they will come to pick her up.”

Ann gave us an incredible gift in those final days. Though it was an excruciating week, we knew that we were being held by someone who was only a phone call away.

In the two years since then, I’ve often thought about Ann and the important role she played in our lives. She was much more than what can fit in the title of “palliative care nurse”. She was facilitator, coach, and guide. By offering gentle, nonjudgmental support and guidance, she helped us walk one of the most difficult journeys of our lives.

The work that Ann did can be defined by a term that’s become common in some of the circles in which I work. She was holding space for us.

What does it mean to hold space for someone else? It means that we are willing to walk alongside another person in whatever journey they’re on without judging them, making them feel inadequate, trying to fix them, or trying to impact the outcome. When we hold space for other people, we open our hearts, offer unconditional support, and let go of judgement and control.

Sometimes we find ourselves holding space for people while they hold space for others. In our situation, for example, Ann was holding space for us while we held space for Mom. Though I know nothing about her support system, I suspect that there are others holding space for Ann as she does this challenging and meaningful work. It’s virtually impossible to be a strong space holder unless we have others who will hold space for us. Even the strongest leaders, coaches, nurses, etc., need to know that there are some people with whom they can be vulnerable and weak without fear of being judged.

In my own roles as teacher, facilitator, coach, mother, wife, and friend, etc., I do my best to hold space for other people in the same way that Ann modeled it for me and my siblings. It’s not always easy, because I have a very human tendency to want to fix people, give them advice, or judge them for not being further along the path than they are, but I keep trying because I know that it’s important. At the same time, there are people in my life that I trust to hold space for me.

To truly support people in their own growth, transformation, grief, etc., we can’t do it by taking their power away (ie. trying to fix their problems), shaming them (ie. implying that they should know more than they do), or overwhelming them (ie. giving them more information than they’re ready for). We have to be prepared to step to the side so that they can make their own choices, offer them unconditional love and support, give gentle guidance when it’s needed, and make them feel safe even when they make mistakes.

Holding space is not something that’s exclusive to facilitators, coaches, or palliative care nurses. It is something that ALL of us can do for each other – for our partners, children, friends, neighbours, and even strangers who strike up conversations as we’re riding the bus to work.

Here are the lessons I’ve learned from Ann and others who have held space for me.

- Give people permission to trust their own intuition and wisdom. When we were supporting Mom in her final days, we had no experience to rely on, and yet, intuitively, we knew what was needed. We knew how to carry her shrinking body to the washroom, we knew how to sit and sing hymns to her, and we knew how to love her. We even knew when it was time to inject the medication that would help ease her pain. In a very gentle way, Ann let us know that we didn’t need to do things according to some arbitrary health care protocol – we simply needed to trust our intuition and accumulated wisdom from the many years we’d loved Mom.

- Give people only as much information as they can handle. Ann gave us some simple instructions and left us with a few handouts, but did not overwhelm us with far more than we could process in our tender time of grief. Too much information would have left us feeling incompetent and unworthy.

- Don’t take their power away. When we take decision-making power out of people’s hands, we leave them feeling useless and incompetent. There may be some times when we need to step in and make hard decisions for other people (ie. when they’re dealing with an addiction and an intervention feels like the only thing that will save them), but in almost every other case, people need the autonomy to make their own choices (even our children). Ann knew that we needed to feel empowered in making decisions on our Mom’s behalf, and so she offered support but never tried to direct or control us.

- Keep your own ego out of it. This is a big one. We all get caught in that trap now and then – when we begin to believe that someone else’s success is dependent on our intervention, or when we think that their failure reflects poorly on us, or when we’re convinced that whatever emotions they choose to unload on us are about us instead of them. It’s a trap I’ve occasionally found myself slipping into when I teach. I can become more concerned about my own success (Do the students like me? Do their marks reflect on my ability to teach? Etc.) than about the success of my students. But that doesn’t serve anyone – not even me. To truly support their growth, I need to keep my ego out of it and create the space where they have the opportunity to grow and learn.

- Make them feel safe enough to fail. When people are learning, growing, or going through grief or transition, they are bound to make some mistakes along the way. When we, as their space holders, withhold judgement and shame, we offer them the opportunity to reach inside themselves to find the courage to take risks and the resilience to keep going even when they fail. When we let them know that failure is simply a part of the journey and not the end of the world, they’ll spend less time beating themselves up for it and more time learning from their mistakes.

- Give guidance and help with humility and thoughtfulness. A wise space holder knows when to withhold guidance (ie. when it makes a person feel foolish and inadequate) and when to offer it gently (ie. when a person asks for it or is too lost to know what to ask for). Though Ann did not take our power or autonomy away, she did offer to come and give Mom baths and do some of the more challenging parts of caregiving. This was a relief to us, as we had no practice at it and didn’t want to place Mom in a position that might make her feel shame (ie. having her children see her naked). This is a careful dance that we all must do when we hold space for other people. Recognizing the areas in which they feel most vulnerable and incapable and offering the right kind of help without shaming them takes practice and humility.

- Create a container for complex emotions, fear, trauma, etc. When people feel that they are held in a deeper way than they are used to, they feel safe enough to allow complex emotions to surface that might normally remain hidden. Someone who is practiced at holding space knows that this can happen and will be prepared to hold it in a gentle, supportive, and nonjudgmental way. In The Circle Way, we talk about “holding the rim” for people. The circle becomes the space where people feel safe enough to fall apart without fearing that this will leave them permanently broken or that they will be shamed by others in the room. Someone is always there to offer strength and courage. This is not easy work, and it is work that I continue to learn about as I host increasingly more challenging conversations. We cannot do it if we are overly emotional ourselves, if we haven’t done the hard work of looking into our own shadow, or if we don’t trust the people we are holding space for. In Ann’s case, she did this by showing up with tenderness, compassion, and confidence. If she had shown up in a way that didn’t offer us assurance that she could handle difficult situations or that she was afraid of death, we wouldn’t have been able to trust her as we did.

- Allow them to make different decisions and to have different experiences than you would. Holding space is about respecting each person’s differences and recognizing that those differences may lead to them making choices that we would not make. Sometimes, for example, they make choices based on cultural norms that we can’t understand from within our own experience. When we hold space, we release control and we honour differences. This showed up, for example, in the way that Ann supported us in making decisions about what to do with Mom’s body after her spirit was no longer housed there. If there had been some ritual that we felt we needed to conduct before releasing her body, we were free to do that in the privacy of Mom’s home.

Holding space is not something that we can master overnight, or that can be adequately addressed in a list of tips like the ones I’ve just given. It’s a complex practice that evolves as we practice it, and it is unique to each person and each situation.

It is my intention to be a life-long learning in what it means to hold space for other people, so if you have experience that’s different than mine and want to add anything to this post, please add that in the comments or send me a message.

************

This post continues to travel around the world and has been shared in many interesting places, including a Harvard Business Review article, Beyond Automation, and a Grist Magazine article, 48 hours that changed the future of the rainforest. It served as the catalyst for my book, The Art of Holding Space, and our organization, the Centre for Holding Space.

This article has been translated into a number of languages (by volunteers):

Portuguese

Turkish

German

Dutch

Russian

Farsi

Spanish

Italian

Romanian

Chinese (no link currently available)

Follow-up pieces about holding space:

How to hold space for yourself first

What’s the opposite of holding space?

Sometimes holding space feels like doing nothing

Sometimes you have to write on the walls: Some thoughts on holding space for other people’s personal growth

On holding space when there is an imbalance of power and privilege

Leave space for others to fill your needs

What the circle holds

An unresolved story that I don’t know how to tell

Holding liminal space (moving beyond the cliché into deeper space)

If you’re looking for a pdf version for printing and/or passing around to others, you can download it here. You’re welcome to share it, but if you want to re-publish any part of it, please contact me.

Interested in more articles like this? Join me at A Tender Space on Substack, or add your email address below.

by Heather Plett | Feb 18, 2015 | circle, Community, Leadership, Uncategorized

“The moment we commit ourselves to going on this journey, we start to encounter our three principal enemies: the voice of doubt and judgment (shutting down the open mind), the voice of cynicism (shutting down the open heart), and the voice of fear (shutting down the open will).” – Otto Sharmer

Lessons in colonialism and cultural relations

Recently I had the opportunity to facilitate a retreat for the staff and board members of a local non-profit. At the retreat, we played a game called Barnga, an inter-cultural learning game that gives people the opportunity to experience a little of what it feels like to be a “stranger in a strange land”.

To play Barnga, people sit at tables of four. Each table is given a simple set of rules and a deck of cards. After reading the rules, they begin to play a couple of practice rounds. Once they’re comfortable with the rules of play, they are instructed to play the rest of the game in silence.

After 15 or 20 minutes of playing in silence, the person who won the most tricks at each table is invited to move to another table. The person who won the least tricks moves to the table in the opposite direction. All of the rules sheets are removed from the tables.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

Newcomers (ie. immigrants) have now arrived in a place where they expect the rules to be the same, find out after making a few mistakes that they are in fact different, and have no shared language to figure out what they’re doing wrong. Around the room you can see the confusion and frustration begin to grow as people try to adapt to the new rules, and those at the table try to use hand gestures and other creative means to let them know what they’re doing wrong.

After another 15 or 20 minutes, the winners and losers move to new tables and the game begins again. This time, people are less surprised to find out there are different rules and more prepared to adapt and/or help newcomers adapt.

After playing for about 45 minutes, we gathered in a sharing circle to debrief about how the experience had been for people. Some shared how, even though they stayed at the table where the rules hadn’t changed, they began to doubt themselves when others insisted on playing with different rules. Some even chose to give up their own rules entirely, even though they hadn’t moved.

In the group of 20 people, there was one white male and 19 women of mixed races. What was revealing for all of us was what that male was brave enough to admit.

“I just realized what I’ve done,” he said. “I was so confident that I knew the rules of the game and that others didn’t that I took my own rules with me wherever I went and I enforced them regardless of how other people were playing.”

It should be stated that this man is a stay-at-home dad who volunteers his time on the board of a family resource centre. He is by no means the stereotypical, aggressive white male you might assume him to be. He is gracious and kind-hearted, and I applaud him for recognizing what he’d done.

What is equally interesting is that all of the women at the tables he moved to allowed him to enforce his set of rules. Whether they doubted themselves enough to not trust their own memory of the rules, or were peacekeepers who decided it was easier to adapt to someone else who felt stronger about the “right” way to do things, each of them acquiesced.

Without any ill intent on his part, this man inadvertently became the colonizer at each table he moved to. And without recognizing they were doing so, the women at those tables inadvertently allowed themselves to be colonized.

If we had played the game much longer, there may have been a growing realization among the women what was happening, and there might have even been a revolt. On the other hand, he might have simply been allowed to maintain his privilege and move around the room without being challenged.

Making the learning personal

Since that game at last week’s retreat, the universe has found multiple opportunities to reinforce this learning for me. I have been reminded more than once that, despite my best efforts not to do so, I, too, sometimes carry my rules with me and expect others to adapt.

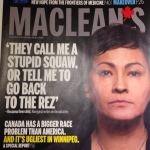

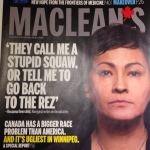

Yesterday, these lessons came from multiple directions. In one case, I was challenged to consider the language I used in the blog post I shared yesterday. In writing about the race relations conversation I helped Rosanna Deerchild to host on Monday night, I mentioned that “we all felt like we’d been punched in the gut” when our city was labeled the “most racist in Canada”. Several people pointed out (and not all kindly) that I was making an assumption that my response to the article was an accurate depiction of how everyone felt. By doing so, I was carrying my rules with me and overlooking the feelings of the very people the article was about.

Not everyone felt like they’d been punched in the gut. Instead, many felt a sense of relief that these stories were finally coming out.

In the critique of my blog post, one person said that my comment about feeling punched in the gut made her feel punched in the gut. Another reflected that mine was a “settler’s narrative”. A third said that I was using “the same sensationalist BS as the Macleans article”.

I was mortified. In my best efforts to enter this conversation with humility and grace, I had inadvertently done the opposite of what I’d intended. Like the man in the Barnga game, I assumed that everyone was playing by the same set of rules.

I quickly edited my blog post to reflect the challenges I’d received, but the problem intensified when I realized that the Macleans journalist who wrote the original article (and who’d flown in for Monday’s gathering) was going to use that exact quote in a follow-up piece in this week’s magazine. Now not only was I opening myself to scrutiny on my blog, I could expect even harsher critique on a national scope.

I quickly sent her a note asking that she adjust the quote. She was on a flight home and by the time she landed, the article was on its way to print. I felt suddenly panicky and deeply ashamed. Fortunately, she was gracious enough to jump into action and she managed to get her editor to adjust the copy before it went to print.

Surviving a shame shitstorm

Last night, I went to bed feeling discouraged and defeated. On top of this challenge, I’d also received another fairly lengthy email about how I’ve let some people down in an entirely different circle, and I was feeling like all of my efforts were resulting in failure.

At 2 a.m., I woke in the middle of what Brene Brown calls a “shame shitstorm”. My mind was reeling with all of my failures. Despite my best efforts to create spaces for safe and authentic conversation, I was inadvertently stepping on toes and enforcing my own rules of engagement.

As one does in the middle of the night, I started second-guessing everything, especially what I’d done at the gathering on Monday night. Was I too bossy when I hosted the gathering? Did I claim space that wasn’t mine to claim? Were my efforts to help really micro-aggressions toward the very people I was trying to build bridges with? Should I just shut up and step out of the conversation?

By 3 a.m., I was ready to yank my blog post off the internet, step away into the shadows, and never again enter into these difficult conversations.

By 4 a.m., I’d managed to talk myself down off the ledge, opened myself to what I needed to learn from these challenges, and was ready to “step back into the arena”.

Some time after 4, I managed to fall back to sleep.

Moving on from here

This morning, in the light of a new day, I recognize this for what it is – an invitation for me to address my own shadow and deepen my own learning of how I carry my own rules with me.

If I am not willing to address the colonizer in me, how can I expect to host spaces where I invite others to do so?

Nobody said this would be easy. There will be more sleepless nights, more shame shitstorms, and more days when my best efforts are met with critique and even anger.

But, as I said in the closing circle on Monday night, I’m going to continue to live with an open heart, even when I don’t know the next right thing to do, and even when I’m criticized for my best efforts.

Because if I’m not willing to change, I have no right to expect others to do so.

by Heather Plett | Feb 17, 2015 | circle, Community, connection, courage, Leadership, Uncategorized

What do you do when your city has been named the “most racist in Canada“?

Some people get defensive, pick holes in the article, and do everything to prove that the label is wrong.

Some people ignore it and go on living the same way they always have.

And some people say “This is not right. What can we do about it?”

When that story came out, some of us felt like we’d been punched in the gut. Though it’s no surprise to most of us that there’s racism here, this showed an even darker side to our city than many of us (especially those who, like me, sometimes forget to turn our gaze beyond our bubble of white privilege) had acknowledged. Insulting our city is like insulting our family. Nobody likes to hear how much ugliness exists in one’s family.

Note: I have been challenged to reflect on my language in the above paragraph. Originally it said “all of us felt like we’d been punched in the gut” and that is not an accurate reflection. Instead, some felt like it was a relief that these stories were finally coming out. I appreciate the challenge and will continue to reflect on how I can speak about this issue through a lens that allows all stories to be heard. That’s part of the reason I’m in this conversation – to look inside for the shadow of colonialism within so that I can step beyond that way of seeing the world and serve as a bridge-builder.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, I began to wrestle with what it would mean for me to be a change-maker in my city. I emailed the mayor and offered to help host conversations, I sat in circle at the Indigenous Family Centre, I accepted the invitation of the drum, and I was cracked open by a sweat lodge.

I shared my interest in hosting conversations around racism on Facebook, and then I waited for the right opportunity to present itself. I tried to be as intentional as possible not to enter the conversation as a “colonizer who thinks she has the answer.” It didn’t take long for that to happen.

Rosanna Deerchild was one of the people quoted in the Macleans article, and her face made it to the front cover of the magazine. Unwillingly and unexpectedly, she became the poster child for racism. Being the wise and wonderful woman that she is, though, she chose to use that opportunity to make good things happen. She posted on her own Facebook page that she wanted to gather people together around the dinner table to have meaningful conversations about racism. A mutual friend connected me to her conversation, and I sent her a message offering to help facilitate the conversation. She took me up on it.

Rosanna Deerchild was one of the people quoted in the Macleans article, and her face made it to the front cover of the magazine. Unwillingly and unexpectedly, she became the poster child for racism. Being the wise and wonderful woman that she is, though, she chose to use that opportunity to make good things happen. She posted on her own Facebook page that she wanted to gather people together around the dinner table to have meaningful conversations about racism. A mutual friend connected me to her conversation, and I sent her a message offering to help facilitate the conversation. She took me up on it.

At the same time, a few other people jumped in and said “count me in too”. Clare MacKay from The Forks said “we’ll provide a space and an international feast”. Angela Chalmers and Sheryl Peters from As it Happened Productions said “we’d like to film the evening”.

With just one short meeting, less than a week before it was set to happen, the five of us planned an evening called “Race Relations and the Path Forward – A Dinner and Discussion with Rosanna Deerchild”. We started sending out invitations, and before long, we had a list of over 50 people who said “I want to be part of this”. Lots of other people said “I can’t make it, but will be with you in spirit.”

In the end, a beautifully diverse group of over 80 people gathered.

We started with a hearty meal, and then we moved into a World Cafe conversation process. In the beginning, everyone was invited to move around the room and sit at tables where they didn’t know the other people. Each table was covered with paper and there were coloured markers for doodling, taking notes, and writing their names.

Before the conversations began, I talked about the importance of listening and shared with them the four levels of listening from Leading from the Emerging Future.

- Downloading:

the listener hears ideas and these merely reconfirm what the listener already knows

- Factual listening:

the listener tries to listen to the facts even if those facts contradict their own theories or ideas

- Empathic listening

: the listener is willing to see reality from the perspective of the other and sense the other’s circumstances

- Generative listening

: the listener forms a space of deep attention that allows an emerging future to “land” or manifest

“What we really want in this room,” I said, “is to move into generative listening. We want to engage in the kind of listening that invites new things to grow.”

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

For the first round of conversation, everyone was invited to get to know each other by sharing who they were, where they were from, and what misconceptions people might have about them. (For example, I am a suburban white mom who drives a minivan, so people may be inclined to jump to certain conclusions about me based on that information.)

After about 15 minutes, I asked that one person remain at the table to serve as the “culture keeper” for that table, holding the memories of the earlier conversations and bringing them into the new conversation when appropriate. Everyone else at the table was asked to be “ambassadors”, bringing their ideas and stories to new tables.

For the second round of conversation, I invited people to share stories of racism in their communities and to talk about the challenges and opportunities that exist. After another 15 minutes, the culture keepers stayed at the tables and the ambassadors carried their ideas to another new table.

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

In the third round of conversation, they were asked to begin to think of possibilities and ideas and to consider “what can we do right now about these challenges and opportunities?”

The one limitation of being the facilitator is that I couldn’t engage fully in the conversations. Instead, I floated around the room listening in where I could. This felt a little disappointing to me, as I would have liked to have immersed myself in the stories and ideas, but at the same time, circling the room gave me the sense that I was helping to hold the edges of the container, creating the space where rich conversation could happen.

After the conversation time had ended, the culture keepers were invited to the front of the room to share the essence of what they’d heard at their tables. Some talked about the need to start in the education system, ensuring that our youth are being accurately taught the Indigenous history of our country, others talked about how this needs to be a political issue and we need to insist that our politicians take these concerns seriously, and still others talked about how we each need to start small, building more one-on-one relationships with people from other cultures. One young woman shared her personal story of being bullied in school and how difficult it is to find a place where she is allowed to “just be herself”. Another woman shared about how hard she has had to work to be taken seriously as an educated Indigenous woman.

After the conversation time had ended, the culture keepers were invited to the front of the room to share the essence of what they’d heard at their tables. Some talked about the need to start in the education system, ensuring that our youth are being accurately taught the Indigenous history of our country, others talked about how this needs to be a political issue and we need to insist that our politicians take these concerns seriously, and still others talked about how we each need to start small, building more one-on-one relationships with people from other cultures. One young woman shared her personal story of being bullied in school and how difficult it is to find a place where she is allowed to “just be herself”. Another woman shared about how hard she has had to work to be taken seriously as an educated Indigenous woman.

One of the people who shared mentioned that the Macleans article was a “gift wrapped in barbed wire”. Those of us in the room have chosen to unwrap the barbed wire to find the opportunities underneath.

Another person said that the golden rule is not enough and that it is based on a colonizers’ view of the world. “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” has to shift into the platinum rule, “Do unto others as they would have you do unto them.” To illustrate his point, he talked about how Indigenous people go for job interviews and because they don’t look people in the eye and don’t have a firm handshake, people assume they don’t have confidence. “Understand their culture more deeply and you’ll understand more about how to treat them.”

As one person mentioned, “the problem is not in this room”, which was a challenge to us all to have conversations not only with the people who think like us, but with those who think differently. Real change will come when we influence those who hold racist views to see people of different nationalities as equals.

There were many other ideas shared, but my brain couldn’t hold them all at once. I will continue to process this and look back over the notes and flipcharts. And there will be more conversations to follow.

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

After we’d heard from all of the tables, we all stood up from our tables and stepped into a circle. We have been well taught by our Indigenous wisdom-keepers that the circle is the strongest shape, and it seemed the right way to end the evening. Once in the circle, I passed around a stone with the word “courage” engraved on it. “I invite each of you to speak out loud one thing that you want to do with courage to help build more positive race relations in our city.” One by one, we held the stone and spoke our commitment into the circle.

We took the energy and ideas in the room and made it personal. Some of the ideas included “I’ll read more Indigenous authors.” “I’ll teach my children to respect people of all races.” “I’ll take political action.” “I’ll take more pride in my Indigenous identity.” “I will host more conversations like this.” “The next time I hear someone say ‘I’m not racist, but…’ I will challenge them.” “I’ll continue my work with Meet me at the Bell Tower.” “I will bring these ideas to my workplace.” “I will find reasons to spend time in other neighbourhood, outside my comfort zone.”

I didn’t realize until later, when I was looking at the photos taken by Greg Littlejohn, that we were standing under the flags of the world. And the lopsided circle looks a little more like a heart from the angle his photo was taken.

This is my Winnipeg. These eighty people who gathered (and all who supported us in spirit) are what I see when I look at this city. Yes there is racism here. Yes we have injustice to address. Yes we have hard work ahead of us to make sure these ideas don’t evaporate the minute we walk out of the room. AND we have a beautiful opportunity to transform our pain into something beautiful.

We have the will, we have the heart, we have a community of support, and we have the opportunity. A year from now, I hope that a different story will be told about our city.

Note: If you’re wondering “what next?”, I can’t say that for certain yet. I know that this will not be a one-time thing, but I’m not sure what will emerge from it yet. The organizers will be getting together to reflect and dream and plan. And in the meantime, I trust that each person who made a commitment to courage in that circle, will carry that courage into action.

by Heather Plett | Jan 13, 2015 | Community, growth, journey, Leadership

There are many reasons to be silent.

Violence (or the threat of violence) is one reason for silence. When cartoonists are murdered for satire and young school girls are kidnapped or murdered for daring to go to school, the risk of speaking up becomes too great for many people.

Sometimes the violence backfires and the voices become stronger – as in the case of Charlie Hebdo, now publishing three million copies when their normal print run was 60,000. Why? Because those with power and influence stepped in to show support for those whose voices were temporarily silenced. If the world had ignored that violence and millions of people – including many world leaders – hadn’t marched in the streets, would there have been the same outcome? If these twelve dead worked for a small publication in Somalia or Myanmar would we have paid as much attention? I doubt it.

Far too many times (especially when the world mostly ignores their plight, as in Nigeria) violence succeeds and fewer people speak up, fewer people are educated, and the perpetrators of the violence have control.

Violence has long been a tool for the silencing of the dissenting voice. Slaves were tortured or murdered for daring to speak up against their owners. Women were burned at the stake for daring to challenge the dominant culture. Even my own ancestors – the Mennonites – were tortured and murdered for their faith and pacifism.

Most likely every single one of us could look back through our lineage and find at least one period in time when our ancestors were subjected to violence. Some of us still live with that reality day to day.

There is no question that the fear of violence is a powerful force for keeping people silent. It still happens in families where there is abuse and in countries where they flog bloggers for speaking out.

Few of the people who read this article will be subjected to flogging or torture for what we say or write online, and yet… there are many of us who remain silent even when we feel strongly that we should speak out.

Why? Why do we remain silent when we see injustice in our workplaces? Why do we turn the other way when we see someone being bullied? Why do we hesitate to speak when we know there’s a better way to do things?

Because we have a memory of violence in our bones. The more I learn about trauma the more I realize that it affects us in much more subtle and insidious ways than we understand. Some of us have experienced trauma and are easily triggered, but even if we never experienced trauma in our own lifetimes, it can be passed down to us through our DNA. Your ancestors’ trauma may still be causing fear in your own life. Witnessing the trauma of other people subjected to violence may be triggering ancient fear in all of us, causing us to remain silent.

Because we have a memory of violence in our bones. The more I learn about trauma the more I realize that it affects us in much more subtle and insidious ways than we understand. Some of us have experienced trauma and are easily triggered, but even if we never experienced trauma in our own lifetimes, it can be passed down to us through our DNA. Your ancestors’ trauma may still be causing fear in your own life. Witnessing the trauma of other people subjected to violence may be triggering ancient fear in all of us, causing us to remain silent.- Because our brains don’t understand fear. The most ancient part of our brains – the “reptilian brain”, which hasn’t evolved since we were living in caves and discovering fire – is adapted for fight or flight. That part of our brain sees all threats as predators, and so it triggers our instinct to survive. Our lives are much different from our ancestors, and yet there’s a part of our brains that still seeks to protect us from woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed tigers. When our fear of being rejected by a family member for speaking out feels the same as the fear of a sabre-toothed tiger, our reaction is often much stronger than it needs to be.

- Because those who want to keep us silent have learned more subtle ways to do so. In most of the countries where we live, it is no longer acceptable to flog bloggers, but that doesn’t mean we’re not being silenced. Women have been silenced, for example, by being taught that their ideas are silly and irrelevant. Marginalized people have been silenced by being given less access to education. Those with unconventional ideas have been “gaslighted” – gradually convinced that they are crazy for what they believe.

- Because we have created an “every man for himself” culture where those who speak out are often not supported for their courage. We’re all trying to thrive in this competitive environment, and so we feel threatened by other people’s success or courage. When I asked on Facebook what keeps people silent, one of the responses (from a blogger) was about the kinds of haters that show up even in what should be supportive environments. In motherhood forums, for example, people get so caught in internal battles (like whether it is better to be a working-away-from-home parent or a stay-at-home parent) that they forget that they would be much stronger in advocating for positive change in the world if they found a way to work together and support each other. It is much more difficult to speak out when we know we’ll be standing alone.

- Because we don’t understand power and privilege. Those who have access to both power and privilege are often surprised when others remain silent. “Why wouldn’t they just speak up?” they say, as though that were the simplest thing in the world to do. It may be a simple thing, if you have never been oppressed or silenced, but if you’ve been taught that your voice has no value because you are “a woman, an Indian, a person of colour, a lesbian, a Muslim, etc.”, then the courage it takes to speak is exponentially greater. Years and years of conditioning that convinces a person of their inherent lack of value cannot be easily undone.

Several years ago, I visited a village in the poorest part of India. Though I’d traveled in several poor regions in Bangladesh, India, and a few African countries before that, this was the most depressing place I’d ever visited. This was a makeshift village populated by the Musahar people who lived at the edges of fields where they sometimes were hired by the landowners as day labourers but otherwise had to scrounge for their food (sometimes stealing grain from rats – which was why they’d come to be known as “rat eaters”).

Several years ago, I visited a village in the poorest part of India. Though I’d traveled in several poor regions in Bangladesh, India, and a few African countries before that, this was the most depressing place I’d ever visited. This was a makeshift village populated by the Musahar people who lived at the edges of fields where they sometimes were hired by the landowners as day labourers but otherwise had to scrounge for their food (sometimes stealing grain from rats – which was why they’d come to be known as “rat eaters”).

There was a look of deadness in the eyes of the people there – a hopelessness and sense of fatalism. Our local hosts told us that these were the most marginalized people in the whole country. They were the lowest tribe of the lowest caste and so everyone in the village had been raised to believe that they had no more value than the rats that ran through their village.

There was a school not far from the village, but we could find only one boy who attended that school. Though everyone had access to the school, none of the parents were convinced their children were worthy of it.

It was a powerful lesson in what oppression and marginalization can do to people. In other equally poor villages (in Ethiopia, for example) I’d still noticed a sense of pride in the people. The Musahar people showed no sense of pride or self-worth. Essentially, they had been “gaslighted” to believe they were worthless and could ask for no more than what they had.

The next day, my traveling companions and I took a rest day instead of visiting another village. We had enough footage for the documentary we were working on and we needed a break from what was an emotionally exhausting trip.

My colleague, however, opted to visit the second village. He came back to the hotel with a fascinating story. In the second village, a local NGO had been working with the people to educate them about their rights as citizens of India. It hadn’t taken long and these people had a very different outlook on their lives and their values. They were beginning to rally, challenging their local government representatives to give them access to the welfare programs that should have been everyone’s rights (but that people in the first village had never been told about by the corrupt politicians who took what should have been given to the villagers). On the way back to the hotel, in fact, he’d been stopped by a demonstration where the body of a man who’d died of starvation had been laid out on the street to block traffic and call attention to the plight of the Musahar people.

The people in the second village were slowly beginning to understand that they were human and had a right to dignity and survival.

In the coaching and personal growth world that I now find myself in, there is much said about “finding our voices”, “stepping into our power”, and “claiming our sovereignty”. Those are all important ideas, and I speak of them in my work, but I believe that there is work that we need to do before any of those things are possible. Like the Musahar people, those who have been silenced need to be taught of their own value and their own capacity for change before they can be expected to impact positive change.

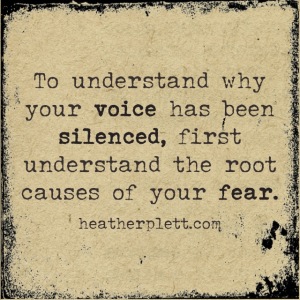

First we need to take a close look at the root causes of the fear that keeps us silent before we’ll be able to change the future.

When we begin to understand power and privilege, when we find practices that help us heal our ancient trauma, when we retrain our brains so that they don’t revert to their most primal conditioning, and when we find supportive communities that will encourage us in our attempts at courage, then we are ready to step into our power and speak with our strongest voices.

Like the Musahar, we need to work on understanding our own value and then we need to work together to have our voices heard.

These are some of the thoughts on my mind as I consider offering another coaching circle based on Pathfinder and/or Lead with Your Wild Heart. If you are interested in joining such a circle, please contact me.

Also, if you are longing to understand your own fear so that you can step forward with courage, consider joining me and Desiree Adaway at Engage!

by Heather Plett | Dec 15, 2014 | Africa, blogging, calling, Community, connection, growth, journey, Uncategorized

Note: Please read all the way to the bottom to find out how you can participate in a special anniversary project and be entered to win a prize.

Note: Please read all the way to the bottom to find out how you can participate in a special anniversary project and be entered to win a prize.

Ten years ago, I started my first blog. It was called Fumbling for Words, because I am a passionate gatherer of words and am always fumbling for the right ones to articulate the complicated things that show up in my brain. And I really, really wanted to find the right words that would connect me with people because, even more than words, I love people. And I love meaningful conversations that connect me to those people.

In the beginning, there was a very particular reason for my blog. I was preparing for my first trip to Africa, a trip I’d been dreaming of since I was a child. I was traveling there in my role as Director of Communications for the non-profit organization I worked for at the time. Though I was delighted with the opportunity, the reason for going complicated the trip for me. I didn’t want to arrive on African soil as a “donor” meeting up with people who were “recipients“. That created too much power differential for me. I wanted to arrive as an equal, a story-catcher, and a listener.

I thought a lot about that, and when I think about things a lot I write about them. Writing is like breathing for me – it helps me exhale what doesn’t serve me and inhale what I need. Here’s an excerpt from my very first blog post.

Will African soil welcome me? Will the colours be as rich as those in my dreams? Will the zebras and lions gaze at me knowingly with eyes that say “we knew you’d come some day”? Will it make me feel hopeful or sad? Or both? Hopeful that this world is a vast and intricate thing of beauty and there is so much more space for me to grow and learn. Or sad that somehow I have hurt these beautiful people by my western greed and western appetite.

I won’t preach from my white-washed Bible. I won’t expect that my English words are somehow endued with greater wisdom than theirs. I will listen and let them teach me. I will open my heart to the hope and the hurt. I will tread lightly on their soil and let the colours wash over me. I will allow the journey to stretch me and I will come back larger than before.

You can read the rest of the post here.

That trip changed me, as did subsequent trips to other parts of Africa and to India and Bangladesh. Each trip cracked me open in both hard  and beautiful ways. They fueled my love of stories and ignited my passion for meaningful conversations that connect people across the barriers of race, gender, language, and class.

and beautiful ways. They fueled my love of stories and ignited my passion for meaningful conversations that connect people across the barriers of race, gender, language, and class.

When you travel with an open heart, you have an opportunity to look deeply into your own heart to examine your privilege, your prejudice, your preconceptions, and your understanding of power. Traveling to Africa caused me to question how the seeds of colonialism had grown, unbeknownst to me, in my own heart. What subtle things do I do in relationships because I assume I have a right to this privilege? What ways do I take for granted that I am entitled to power? And in what ways am I uncomfortable when people assume I have power that I don’t feel I have?

I did my best to walk on African soil with a posture of humility. It’s not always easy though, when they receive you as “rich donor who brought us food”. When I found myself in uncomfortable situations, such as the day we visited a food distribution site and the villagers had been sitting in the hot sun for hours waiting for us to arrive so that we could speak with them and help distribute their food, I dug through my history for stories that might offer some sense of reciprocity and connection.

When I came home from Africa with the responsibility of sharing stories with Canadian donors about where their money was going, I did my best to offer dignity and respect to each person whose stories I shared. I was determined not to use images that branded people as helpless victims, and the stories I told were always about their resourcefulness and ability to thrive even in difficult circumstances. But still… there was always a restlessness in that work, because I was always telling stories for the purpose of raising money rather than sharing stories as a way to build bridges, change paradigms, and find mutual healing.

That work served as a catalyst for me to dig deeper and deeper into what it might mean to build healthy relationships and host meaningful conversations across power imbalances and racial divides. My ongoing inquiry brought me to The Circle Way and The Art of Hosting. The circle, I am convinced, is the best place to start. The circle invites each person in each chair to bring themselves fully into the conversation, to serve as leader and listener, change-maker and healer.

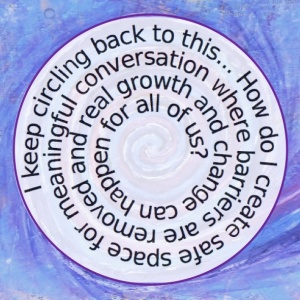

As I reflect back over my ten years of blogging, it’s clear that I keep circling back to the same inquiry that ignited my first blog post and that brought me to the circle. In the 1521 posts I’ve written, and in the work I now do, this question comes back again and again.

How do I create safe space for meaningful conversation where barriers are removed and real growth and change can happen for all of us?

This question took me deeper and deeper into this work, inviting me into more and more challenging conversations and situations. It led me away from that non-profit job into self-employment, it helped me build relationships with people all over the world who are hosting conversations like this, and it led me again and again back to the circle. This blog became a kind of virtual circle, inviting people into the conversation. Collectively, those of us who have gathered here (and on connected social media) have been having meaningful conversations, removing barriers, and encouraging each other to change and grow.

This question took me deeper and deeper into this work, inviting me into more and more challenging conversations and situations. It led me away from that non-profit job into self-employment, it helped me build relationships with people all over the world who are hosting conversations like this, and it led me again and again back to the circle. This blog became a kind of virtual circle, inviting people into the conversation. Collectively, those of us who have gathered here (and on connected social media) have been having meaningful conversations, removing barriers, and encouraging each other to change and grow.

Together we have been learning to live more authentically, more courageously, and more compassionately. We’ve stretched ourselves, we’ve shared grief stories, we’ve celebrated together, and we’ve grown our relationships.

As I look back over 10 years of blogging, I look back to where it all began – back to that place where my tender, open heart, was ready to be stretched and changed, and ready to be in relationship with people who would change me. You, my dear reader, have stretched and changed me, just like those people I met in Africa. For that I am deeply grateful.

Though I haven’t been back to Africa since I left that job, it continues to hold a place in my heart. It’s beautiful, yes, and I’ve met amazing people there, but I think the piece that keeps calling me back is the opportunity to peer into my own privilege and to dive in to relationships that help me grow.

These things are also possible here at home, and I’m finding more and more ways to engage with this inquiry right here where I live, where the most challenging issue is the way that we as descendents of the European settlers have separated ourselves from the First Nations people through colonization and margnalization. I am seeking to understand more about the intersection between power and love and how we can build bridges by understanding both.

When my business (and blog reach) was growing earlier this year (thanks to you), I knew that I needed to use whatever influence I have for good, beyond my own income. I wanted an opportunity to support people with access to less privilege than I enjoy without allowing my support of them to contribute to the power imbalance. The best way that I knew to do this was to let someone from within that community take the lead, someone who was stepping into her own power and was already working to serve a more beautiful world. I didn’t need to look far. My friend (who’d been a youth intern on my team for a year while I worked in non-profit) Nestar Lakot Okella had started a school in the village where she grew up in Uganda.

Because I already have a high level of trust in Nestar’s ability to lead and be a change-maker, it didn’t take much for me step alongside as an ally in support of Uganda Kitgum Education Foundation. I hosted my first fundraiser in celebration of my birthday in May, and with your help, my dear readers, we were able to send more than $2000 to the school. Since then I’ve been sending a portion of the proceeds from programs such as Mandala Discovery and The Spiral Path.

This past week, I received a set of photos from Nestar and they brought tears to my eyes. They were very simple photos of men making chairs, but they meant so much.

This past week, I received a set of photos from Nestar and they brought tears to my eyes. They were very simple photos of men making chairs, but they meant so much.

Nestar’s note said: “I wanted to share pictures we got from Kitgum. We are able to order 125 chairs and 125 tables and 1 bookshelf for every classroom. All the items are being made locally in Kitgum, so the local community can also benefit from our school project through the jobs created.

“Thank you for your contribution which has partially made this possible. No more learning on the floor for our students next year, YES! :)”

It delights me to no end to imagine the children returning to their classrooms after their winter break ends in January to find out they now have chairs, tables, and bookshelves in their classrooms!

Today, as I celebrate 10 years of blogging, it seems beautifully appropriate that what started as a way to capture my stories of Africa has brought me full circle to this place where I can use my blog as a platform to support the learning and empowerment of young people in Africa whose school was started by a leader from their own community. Some day I would love to be in relationship with the students of that school, not as a benefactor to beneficiaries, but as co-learners and co-creators, working to make the work a little bit better.

And that brings me to my special anniversary campaign.

I want to continue to support the education of children in Uganda AND I want to support my own dream of taking my writing to a broader audience.

I love the idea of us learning and growing together in separate parts of the world. I imagine myself sitting in one of those blue chairs in a circle with them, each of us stretching and growing into our capacity, reading books and writing books and learning to be loving, powerful change-makers and leaders.

This is where you come in. I want to invite you to support my 10th Anniversary Book + Books Project:

- The students at UKEF need textbooks. Nestar tells me that there are only one or two textbooks for each classroom and they want to buy more. A textbook costs approximately $12.50, so it wouldn’t take much for us to buy enough for every one of the 300 children at the school.

- I intend to publish a book in 2015. As many of you know, this has been a long held dream of mine. I completed what I thought would be my first published book two years ago, but I set it aside when my mom died and then it never really felt like it had evolved into what it was meant to be. The book is now evolving into one called “Circling around to this” and it will be the story of how I’ve been growing into the question above and how it has led me to circle, labyrinth, mandala, and spiral. (Who knows… I might even visit Africa on a future book tour!)

If we are able to raise $7500, there will be enough to buy textbooks for all of the students AND I’ll have most of what I need to publish a book.

If this blog (or my newsletters or any of my writing) has touched you in any way in the last ten years AND you believe all children should have access to education, there are two ways that you can support this dual fundraising goal:

- Make a donation using the form below. Half of all money donated will be sent to UKEF for textbooks (or for whatever else Nestar decides the money is best used for – I am determined to let her and the school leadership make the best decisions they need to make without this becoming donor-controlled). The other half will be set aside for the publishing costs associated with getting my book into print.

- Make a purchase of anything from my portfolio before December 19th and half of the proceeds will be donated to UKEF and half will go to my publishing fund. You can register for Mandala Discovery in January or for The Spiral Path in February, you can buy A Soulful Year or Lead with Your Wild Heart, you can sign up for coaching, or you can buy something from my Etsy shop.

To make this a little more interesting, I’ve put together a prize package. At 5 p.m. central on Friday, December 19th, I’ll pick a name from all of those who have contributed, and one lucky winner will receive the following (total value $204 + shipping):

Thank you in advance for making a contribution to the 10th Anniversary Book + Books Project!

Note: if you wish to dedicate your donation to only one of the two causes I’m fundraising for, indicate that in the comment box and I will honour your request.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

Several years ago, I visited a village in the poorest part of India. Though I’d traveled in several poor regions in Bangladesh, India, and a few African countries before that, this was the most depressing place I’d ever visited. This was a makeshift village populated by the

Several years ago, I visited a village in the poorest part of India. Though I’d traveled in several poor regions in Bangladesh, India, and a few African countries before that, this was the most depressing place I’d ever visited. This was a makeshift village populated by the