by Heather Plett | Feb 18, 2015 | circle, Community, Leadership, Uncategorized

“The moment we commit ourselves to going on this journey, we start to encounter our three principal enemies: the voice of doubt and judgment (shutting down the open mind), the voice of cynicism (shutting down the open heart), and the voice of fear (shutting down the open will).” – Otto Sharmer

Lessons in colonialism and cultural relations

Recently I had the opportunity to facilitate a retreat for the staff and board members of a local non-profit. At the retreat, we played a game called Barnga, an inter-cultural learning game that gives people the opportunity to experience a little of what it feels like to be a “stranger in a strange land”.

To play Barnga, people sit at tables of four. Each table is given a simple set of rules and a deck of cards. After reading the rules, they begin to play a couple of practice rounds. Once they’re comfortable with the rules of play, they are instructed to play the rest of the game in silence.

After 15 or 20 minutes of playing in silence, the person who won the most tricks at each table is invited to move to another table. The person who won the least tricks moves to the table in the opposite direction. All of the rules sheets are removed from the tables.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

Newcomers (ie. immigrants) have now arrived in a place where they expect the rules to be the same, find out after making a few mistakes that they are in fact different, and have no shared language to figure out what they’re doing wrong. Around the room you can see the confusion and frustration begin to grow as people try to adapt to the new rules, and those at the table try to use hand gestures and other creative means to let them know what they’re doing wrong.

After another 15 or 20 minutes, the winners and losers move to new tables and the game begins again. This time, people are less surprised to find out there are different rules and more prepared to adapt and/or help newcomers adapt.

After playing for about 45 minutes, we gathered in a sharing circle to debrief about how the experience had been for people. Some shared how, even though they stayed at the table where the rules hadn’t changed, they began to doubt themselves when others insisted on playing with different rules. Some even chose to give up their own rules entirely, even though they hadn’t moved.

In the group of 20 people, there was one white male and 19 women of mixed races. What was revealing for all of us was what that male was brave enough to admit.

“I just realized what I’ve done,” he said. “I was so confident that I knew the rules of the game and that others didn’t that I took my own rules with me wherever I went and I enforced them regardless of how other people were playing.”

It should be stated that this man is a stay-at-home dad who volunteers his time on the board of a family resource centre. He is by no means the stereotypical, aggressive white male you might assume him to be. He is gracious and kind-hearted, and I applaud him for recognizing what he’d done.

What is equally interesting is that all of the women at the tables he moved to allowed him to enforce his set of rules. Whether they doubted themselves enough to not trust their own memory of the rules, or were peacekeepers who decided it was easier to adapt to someone else who felt stronger about the “right” way to do things, each of them acquiesced.

Without any ill intent on his part, this man inadvertently became the colonizer at each table he moved to. And without recognizing they were doing so, the women at those tables inadvertently allowed themselves to be colonized.

If we had played the game much longer, there may have been a growing realization among the women what was happening, and there might have even been a revolt. On the other hand, he might have simply been allowed to maintain his privilege and move around the room without being challenged.

Making the learning personal

Since that game at last week’s retreat, the universe has found multiple opportunities to reinforce this learning for me. I have been reminded more than once that, despite my best efforts not to do so, I, too, sometimes carry my rules with me and expect others to adapt.

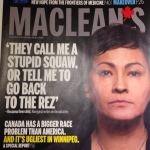

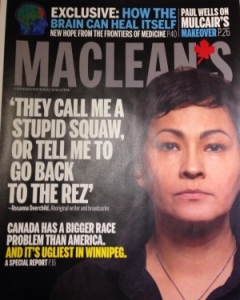

Yesterday, these lessons came from multiple directions. In one case, I was challenged to consider the language I used in the blog post I shared yesterday. In writing about the race relations conversation I helped Rosanna Deerchild to host on Monday night, I mentioned that “we all felt like we’d been punched in the gut” when our city was labeled the “most racist in Canada”. Several people pointed out (and not all kindly) that I was making an assumption that my response to the article was an accurate depiction of how everyone felt. By doing so, I was carrying my rules with me and overlooking the feelings of the very people the article was about.

Not everyone felt like they’d been punched in the gut. Instead, many felt a sense of relief that these stories were finally coming out.

In the critique of my blog post, one person said that my comment about feeling punched in the gut made her feel punched in the gut. Another reflected that mine was a “settler’s narrative”. A third said that I was using “the same sensationalist BS as the Macleans article”.

I was mortified. In my best efforts to enter this conversation with humility and grace, I had inadvertently done the opposite of what I’d intended. Like the man in the Barnga game, I assumed that everyone was playing by the same set of rules.

I quickly edited my blog post to reflect the challenges I’d received, but the problem intensified when I realized that the Macleans journalist who wrote the original article (and who’d flown in for Monday’s gathering) was going to use that exact quote in a follow-up piece in this week’s magazine. Now not only was I opening myself to scrutiny on my blog, I could expect even harsher critique on a national scope.

I quickly sent her a note asking that she adjust the quote. She was on a flight home and by the time she landed, the article was on its way to print. I felt suddenly panicky and deeply ashamed. Fortunately, she was gracious enough to jump into action and she managed to get her editor to adjust the copy before it went to print.

Surviving a shame shitstorm

Last night, I went to bed feeling discouraged and defeated. On top of this challenge, I’d also received another fairly lengthy email about how I’ve let some people down in an entirely different circle, and I was feeling like all of my efforts were resulting in failure.

At 2 a.m., I woke in the middle of what Brene Brown calls a “shame shitstorm”. My mind was reeling with all of my failures. Despite my best efforts to create spaces for safe and authentic conversation, I was inadvertently stepping on toes and enforcing my own rules of engagement.

As one does in the middle of the night, I started second-guessing everything, especially what I’d done at the gathering on Monday night. Was I too bossy when I hosted the gathering? Did I claim space that wasn’t mine to claim? Were my efforts to help really micro-aggressions toward the very people I was trying to build bridges with? Should I just shut up and step out of the conversation?

By 3 a.m., I was ready to yank my blog post off the internet, step away into the shadows, and never again enter into these difficult conversations.

By 4 a.m., I’d managed to talk myself down off the ledge, opened myself to what I needed to learn from these challenges, and was ready to “step back into the arena”.

Some time after 4, I managed to fall back to sleep.

Moving on from here

This morning, in the light of a new day, I recognize this for what it is – an invitation for me to address my own shadow and deepen my own learning of how I carry my own rules with me.

If I am not willing to address the colonizer in me, how can I expect to host spaces where I invite others to do so?

Nobody said this would be easy. There will be more sleepless nights, more shame shitstorms, and more days when my best efforts are met with critique and even anger.

But, as I said in the closing circle on Monday night, I’m going to continue to live with an open heart, even when I don’t know the next right thing to do, and even when I’m criticized for my best efforts.

Because if I’m not willing to change, I have no right to expect others to do so.

by Heather Plett | Feb 17, 2015 | circle, Community, connection, courage, Leadership, Uncategorized

What do you do when your city has been named the “most racist in Canada“?

Some people get defensive, pick holes in the article, and do everything to prove that the label is wrong.

Some people ignore it and go on living the same way they always have.

And some people say “This is not right. What can we do about it?”

When that story came out, some of us felt like we’d been punched in the gut. Though it’s no surprise to most of us that there’s racism here, this showed an even darker side to our city than many of us (especially those who, like me, sometimes forget to turn our gaze beyond our bubble of white privilege) had acknowledged. Insulting our city is like insulting our family. Nobody likes to hear how much ugliness exists in one’s family.

Note: I have been challenged to reflect on my language in the above paragraph. Originally it said “all of us felt like we’d been punched in the gut” and that is not an accurate reflection. Instead, some felt like it was a relief that these stories were finally coming out. I appreciate the challenge and will continue to reflect on how I can speak about this issue through a lens that allows all stories to be heard. That’s part of the reason I’m in this conversation – to look inside for the shadow of colonialism within so that I can step beyond that way of seeing the world and serve as a bridge-builder.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, I began to wrestle with what it would mean for me to be a change-maker in my city. I emailed the mayor and offered to help host conversations, I sat in circle at the Indigenous Family Centre, I accepted the invitation of the drum, and I was cracked open by a sweat lodge.

I shared my interest in hosting conversations around racism on Facebook, and then I waited for the right opportunity to present itself. I tried to be as intentional as possible not to enter the conversation as a “colonizer who thinks she has the answer.” It didn’t take long for that to happen.

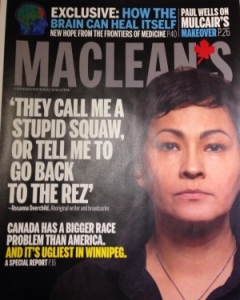

Rosanna Deerchild was one of the people quoted in the Macleans article, and her face made it to the front cover of the magazine. Unwillingly and unexpectedly, she became the poster child for racism. Being the wise and wonderful woman that she is, though, she chose to use that opportunity to make good things happen. She posted on her own Facebook page that she wanted to gather people together around the dinner table to have meaningful conversations about racism. A mutual friend connected me to her conversation, and I sent her a message offering to help facilitate the conversation. She took me up on it.

Rosanna Deerchild was one of the people quoted in the Macleans article, and her face made it to the front cover of the magazine. Unwillingly and unexpectedly, she became the poster child for racism. Being the wise and wonderful woman that she is, though, she chose to use that opportunity to make good things happen. She posted on her own Facebook page that she wanted to gather people together around the dinner table to have meaningful conversations about racism. A mutual friend connected me to her conversation, and I sent her a message offering to help facilitate the conversation. She took me up on it.

At the same time, a few other people jumped in and said “count me in too”. Clare MacKay from The Forks said “we’ll provide a space and an international feast”. Angela Chalmers and Sheryl Peters from As it Happened Productions said “we’d like to film the evening”.

With just one short meeting, less than a week before it was set to happen, the five of us planned an evening called “Race Relations and the Path Forward – A Dinner and Discussion with Rosanna Deerchild”. We started sending out invitations, and before long, we had a list of over 50 people who said “I want to be part of this”. Lots of other people said “I can’t make it, but will be with you in spirit.”

In the end, a beautifully diverse group of over 80 people gathered.

We started with a hearty meal, and then we moved into a World Cafe conversation process. In the beginning, everyone was invited to move around the room and sit at tables where they didn’t know the other people. Each table was covered with paper and there were coloured markers for doodling, taking notes, and writing their names.

Before the conversations began, I talked about the importance of listening and shared with them the four levels of listening from Leading from the Emerging Future.

- Downloading:

the listener hears ideas and these merely reconfirm what the listener already knows

- Factual listening:

the listener tries to listen to the facts even if those facts contradict their own theories or ideas

- Empathic listening

: the listener is willing to see reality from the perspective of the other and sense the other’s circumstances

- Generative listening

: the listener forms a space of deep attention that allows an emerging future to “land” or manifest

“What we really want in this room,” I said, “is to move into generative listening. We want to engage in the kind of listening that invites new things to grow.”

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

For the first round of conversation, everyone was invited to get to know each other by sharing who they were, where they were from, and what misconceptions people might have about them. (For example, I am a suburban white mom who drives a minivan, so people may be inclined to jump to certain conclusions about me based on that information.)

After about 15 minutes, I asked that one person remain at the table to serve as the “culture keeper” for that table, holding the memories of the earlier conversations and bringing them into the new conversation when appropriate. Everyone else at the table was asked to be “ambassadors”, bringing their ideas and stories to new tables.

For the second round of conversation, I invited people to share stories of racism in their communities and to talk about the challenges and opportunities that exist. After another 15 minutes, the culture keepers stayed at the tables and the ambassadors carried their ideas to another new table.

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

In the third round of conversation, they were asked to begin to think of possibilities and ideas and to consider “what can we do right now about these challenges and opportunities?”

The one limitation of being the facilitator is that I couldn’t engage fully in the conversations. Instead, I floated around the room listening in where I could. This felt a little disappointing to me, as I would have liked to have immersed myself in the stories and ideas, but at the same time, circling the room gave me the sense that I was helping to hold the edges of the container, creating the space where rich conversation could happen.

After the conversation time had ended, the culture keepers were invited to the front of the room to share the essence of what they’d heard at their tables. Some talked about the need to start in the education system, ensuring that our youth are being accurately taught the Indigenous history of our country, others talked about how this needs to be a political issue and we need to insist that our politicians take these concerns seriously, and still others talked about how we each need to start small, building more one-on-one relationships with people from other cultures. One young woman shared her personal story of being bullied in school and how difficult it is to find a place where she is allowed to “just be herself”. Another woman shared about how hard she has had to work to be taken seriously as an educated Indigenous woman.

After the conversation time had ended, the culture keepers were invited to the front of the room to share the essence of what they’d heard at their tables. Some talked about the need to start in the education system, ensuring that our youth are being accurately taught the Indigenous history of our country, others talked about how this needs to be a political issue and we need to insist that our politicians take these concerns seriously, and still others talked about how we each need to start small, building more one-on-one relationships with people from other cultures. One young woman shared her personal story of being bullied in school and how difficult it is to find a place where she is allowed to “just be herself”. Another woman shared about how hard she has had to work to be taken seriously as an educated Indigenous woman.

One of the people who shared mentioned that the Macleans article was a “gift wrapped in barbed wire”. Those of us in the room have chosen to unwrap the barbed wire to find the opportunities underneath.

Another person said that the golden rule is not enough and that it is based on a colonizers’ view of the world. “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” has to shift into the platinum rule, “Do unto others as they would have you do unto them.” To illustrate his point, he talked about how Indigenous people go for job interviews and because they don’t look people in the eye and don’t have a firm handshake, people assume they don’t have confidence. “Understand their culture more deeply and you’ll understand more about how to treat them.”

As one person mentioned, “the problem is not in this room”, which was a challenge to us all to have conversations not only with the people who think like us, but with those who think differently. Real change will come when we influence those who hold racist views to see people of different nationalities as equals.

There were many other ideas shared, but my brain couldn’t hold them all at once. I will continue to process this and look back over the notes and flipcharts. And there will be more conversations to follow.

photo credit: Greg Littlejohn

After we’d heard from all of the tables, we all stood up from our tables and stepped into a circle. We have been well taught by our Indigenous wisdom-keepers that the circle is the strongest shape, and it seemed the right way to end the evening. Once in the circle, I passed around a stone with the word “courage” engraved on it. “I invite each of you to speak out loud one thing that you want to do with courage to help build more positive race relations in our city.” One by one, we held the stone and spoke our commitment into the circle.

We took the energy and ideas in the room and made it personal. Some of the ideas included “I’ll read more Indigenous authors.” “I’ll teach my children to respect people of all races.” “I’ll take political action.” “I’ll take more pride in my Indigenous identity.” “I will host more conversations like this.” “The next time I hear someone say ‘I’m not racist, but…’ I will challenge them.” “I’ll continue my work with Meet me at the Bell Tower.” “I will bring these ideas to my workplace.” “I will find reasons to spend time in other neighbourhood, outside my comfort zone.”

I didn’t realize until later, when I was looking at the photos taken by Greg Littlejohn, that we were standing under the flags of the world. And the lopsided circle looks a little more like a heart from the angle his photo was taken.

This is my Winnipeg. These eighty people who gathered (and all who supported us in spirit) are what I see when I look at this city. Yes there is racism here. Yes we have injustice to address. Yes we have hard work ahead of us to make sure these ideas don’t evaporate the minute we walk out of the room. AND we have a beautiful opportunity to transform our pain into something beautiful.

We have the will, we have the heart, we have a community of support, and we have the opportunity. A year from now, I hope that a different story will be told about our city.

Note: If you’re wondering “what next?”, I can’t say that for certain yet. I know that this will not be a one-time thing, but I’m not sure what will emerge from it yet. The organizers will be getting together to reflect and dream and plan. And in the meantime, I trust that each person who made a commitment to courage in that circle, will carry that courage into action.

by Heather Plett | Jan 28, 2015 | art of hosting, change, growth, journey, Leadership

“The success of our actions as change-makers does not depend on what we do or how we do it, but on the inner place from which we operate.” – Otto Sharmer

Last week, the city that I love and call home was named “the most racist city in Canada.” That hurt. It felt like someone had insulted my family.

Last week, the city that I love and call home was named “the most racist city in Canada.” That hurt. It felt like someone had insulted my family.

The article mentions many heartbreaking stories of the way that Indigenous people have been treated in our city, and while I wanted to say “but… we’re so NICE here! Really! You have to see the other side too!” I knew that there was undeniable truth I had to face and own. My family isn’t always nice. Neither is my city.

Though I work hard not to be racist, have many Indigenous friends in my circles, and am married to a Metis man, I knew that my response to the article needed to not only be a closer look at my city but a closer look at myself. I may not be overtly racist, but are there ways that I have been complicit in allowing this disease to grow around me? Are there things that I have left unsaid that have given people permission for their racism? Are there ways in which my white privilege has made me blind?

Ever since the summer, when I attended the vigil for Tina Fontaine, a young Indigenous woman whose body was found in the river, I have been feeling some restlessness around this issue. I knew that I was being nudged into some work that would help in the healing of my city and my country, but I didn’t know what that work was. I started by carrying my sadness over the murdered and missing Indigenous women into the Black Hills when I invited women on a lament journey.

Ever since the summer, when I attended the vigil for Tina Fontaine, a young Indigenous woman whose body was found in the river, I have been feeling some restlessness around this issue. I knew that I was being nudged into some work that would help in the healing of my city and my country, but I didn’t know what that work was. I started by carrying my sadness over the murdered and missing Indigenous women into the Black Hills when I invited women on a lament journey.

This week, after the Macleans article came out, our mayor made a courageous choice in how he responded to the article. In a press conference called shortly after the article spread across the internet, he didn’t get defensive, but instead he spoke with vulnerability about his own identity as a Metis man and about how his desire is for his children to be proud of both of the heritages they carry – their mother’s and his. He then invited several Indigenous leaders to speak.

There was something about the mayor’s address that galvanized me into action. I knew it was time for me to step forward and offer what I can. I sent an email and tweet to the mayor, thanking him for what he’d done and then offering my expertise in hosting meaningful conversations. Because I believe that we need to start healing this divide in our city and healing will begin when we sit and look into each others’ eyes and listen deeply to each others’ stories.

After that, I purchased the url letstalkaboutracism.com. I haven’t done anything with it yet, but I know that one of the things I need to do is to invite more people into a conversation around racism and how it wounds us all. I have no idea how to fix this, but I know how to hold space for difficult conversations, so that is what I intend to do. Circles have the capacity to hold deep healing work, and I will find a way to offer them where I can.

Since then, I have had moments of clarity about what needs to be done next, but far more moments of doubt and fear. At present, I am sitting with both the clarity and the doubt, trying to hold both and trying to be present for what wants to be born.

Here are some of the things that are showing up in my internal dialogue:

- Isn’t it a little arrogant to think I have any expertise to offer in this area? There are so many more qualified people than me.

- What if I offend the Indigenous people by offering my ideas, and become like the colonizers who think they have the answers and refuse to listen to the wisdom of the people they’re trying to help?

- There are already many people doing healing work on this issue, and many of them are already holding Indigenous circles. I have nothing unique to contribute.

- What if I host sharing circles and too much trauma and/or conflict shows up in the circle and I don’t know how to hold it?

- What if this is just my ego trying to do something “important” and get attention for me rather than the cause?

And so the conversation in my head goes back and forth. And the conversations outside of my head (with other people) aren’t much different.

At the same time as this has been going on, I have been working through the first two weeks of course material for U Lab: Transforming Business, Society and Self. In one of the course videos, Otto Sharmer talks about the four levels of listening – from downloading (where we listen to confirm habitual judgements), to factual (listening by paying attention to facts and to novel or disconfirming data), to empathic (where we listen with our hearts and not just our minds), and finally to generative (where we move with the person speaking into communion and transformaton).

As soon as I read that, I knew that whatever I do to help create space for healing in my city, it has to start with a place of deep listening – generative listening, where all those in the circle can move into communion and transformation. I also knew, as I sat with that idea, that that generative listening has to begin with me.

If I am to serve in this role, I need to be prepared to move out of my comfort zone, into generative listening with people who have been wounded by racism in our city AND with people who live with racial blindspots. AND (in the words of Otto Sharmer) I need to move out of an ego-system mentality (where I am seeking my own interest first), into a generative, eco-system mentality (where I am seeking the best interest of the community and world around me).

So that is my intention, starting this week. I already have a meeting planned with an Indigenous friend who has contributed to, and wants to teach, an adult curriculum on racism, to find out how I can support her in this work. And I will be meeting with another friend, a talented Indigenous musician, about possible partnership opportunities. And I will be a sitting in an Indigenous sharing circle, listening deeply to their stories.

I am not sharing these stories to say “look at me and all of the good things I’m doing”. That would be my ego talking, and that’s one of the things I’m trying to avoid. Instead, I’m sharing it to say “look at the complexity that a thinking woman (sometimes over-thinking woman) goes through in order to become an effective, and humble, change-maker.

That brings me back to the quote at the top of the page.

“The success of our actions as change-makers does not depend on what we do or how we do it, but on the inner place from which we operate.” – Otto Sharmer

The inner place. That is what will determine the success of our actions. I can have all the smart ideas in the world, and a big network of people to help roll them out, but if I have not done the internal work first, my success will be limited.

If I don’t do the inner work first, then my ego will run rampant and I will stomp all over the people that I say I care about. Or I will suffer from jealousy, or self doubt, or self-centredness, or vindictiveness, or all of the above.

If I don’t do the internal work and ask myself important questions about what is rooted in my ego and what is generative, then I could potentially do more harm than good.

So how do I do that internal work? Here are some of the things that I do:

1. As we say in Art of Hosting work, I host myself first. In other words, I ask of myself whatever I would ask of others I might invite into circle, I look for both my shadows and my strengths, and I do the kind of self-care I would encourage my clients to do when they find themselves in the middle of big shifts.

2. I ask myself a few pointed questions to determine whether the ego is too involved. For example, when my friend came to me to share the work she wants to do, hosting circles in the curriculum she has developed, there was a little ego-voice that spoke up and said “But wait! This was supposed to be YOUR work! If you support her, you’ll have to be in the background.” The moment I heard that voice, I had to ask myself “do you truly want to make a difference around the issue of racism or do you just want to make a name for yourself?” And: “If this is successful in impacting change, but you have only a secondary role, is it still worthwhile?” It didn’t take long for me to know that I wanted to be wholeheartedly behind her work.

3. I pause. As we learn in Theory U, the pause is the most important part – it’s where the really juicy stuff happens. The pause is where we notice patterns that we were too busy to notice before. It’s where the voice of wisdom speaks through the noise. It’s where we are more able to sink into generative listening. In Theory U, we call it “presencing” – a combination of “presence” and “sensing”. There’s a quality of mindfulness in the pause that helps me notice and experience more and be awake to receive more wisdom.

4. I do the practices that help bring me to wise thought and wise action. For me, it’s journaling, art, mandala-making, nature walks, and labyrinth walks. I never make a major decision without spending intentional time in one of those practices. Almost always, something more profound and wise shows up that I wouldn’t have considered earlier.

5. I listen. The ego doesn’t want me to seek input from other people. The ego wants to be in control and not invite partners in to share the spotlight. If I want to move out of ego-system, though, I need to spend time listening for others’ stories and wisdom. This doesn’t mean I listen to EVERYONE. Instead, I use my discretion about who are the right people to seek wise council from. I listen to those who have done their own personal work, whose own egos won’t try to trap me and keep me from succeeding, and who genuinely care about the issue I’m working on.

6. I check in with myself and then move into action when I’m ready. Although the pause, the questions, and the personal practice are all very important, the movement into action is equally important. There have been far too many times when my questions and ego have trapped me in a spiral and I’ve failed to move into action. Just thinking about it won’t impact change. I need to be prepared to act, even if I still have doubt. If I fail in that action, I can always go back and re-enter the presencing stage.

This is an ongoing story and I hope to continue sharing it as it emerges. If you, too, want to become a change-maker, then I’d love to hear from you. What are the processes you go through in order to ensure your “inner place” is healthy and your listening and actions are generative? What issues are currently calling you into action?

If this resonates with you, check out The Spiral Path, which begins February 1st. Based on the three stages of the labyrinth, (release, receive, and return), it invites you to go inward to do this internal work and then to move outward to serve in the way that you are called.

Also… we’re looking for a few more change-makers to attend Engage, a one-of-a-kind retreat that will teach you more about how to do your inner work so that you can move into generative action.

by Heather Plett | Jan 13, 2015 | Community, growth, journey, Leadership

There are many reasons to be silent.

Violence (or the threat of violence) is one reason for silence. When cartoonists are murdered for satire and young school girls are kidnapped or murdered for daring to go to school, the risk of speaking up becomes too great for many people.

Sometimes the violence backfires and the voices become stronger – as in the case of Charlie Hebdo, now publishing three million copies when their normal print run was 60,000. Why? Because those with power and influence stepped in to show support for those whose voices were temporarily silenced. If the world had ignored that violence and millions of people – including many world leaders – hadn’t marched in the streets, would there have been the same outcome? If these twelve dead worked for a small publication in Somalia or Myanmar would we have paid as much attention? I doubt it.

Far too many times (especially when the world mostly ignores their plight, as in Nigeria) violence succeeds and fewer people speak up, fewer people are educated, and the perpetrators of the violence have control.

Violence has long been a tool for the silencing of the dissenting voice. Slaves were tortured or murdered for daring to speak up against their owners. Women were burned at the stake for daring to challenge the dominant culture. Even my own ancestors – the Mennonites – were tortured and murdered for their faith and pacifism.

Most likely every single one of us could look back through our lineage and find at least one period in time when our ancestors were subjected to violence. Some of us still live with that reality day to day.

There is no question that the fear of violence is a powerful force for keeping people silent. It still happens in families where there is abuse and in countries where they flog bloggers for speaking out.

Few of the people who read this article will be subjected to flogging or torture for what we say or write online, and yet… there are many of us who remain silent even when we feel strongly that we should speak out.

Why? Why do we remain silent when we see injustice in our workplaces? Why do we turn the other way when we see someone being bullied? Why do we hesitate to speak when we know there’s a better way to do things?

Because we have a memory of violence in our bones. The more I learn about trauma the more I realize that it affects us in much more subtle and insidious ways than we understand. Some of us have experienced trauma and are easily triggered, but even if we never experienced trauma in our own lifetimes, it can be passed down to us through our DNA. Your ancestors’ trauma may still be causing fear in your own life. Witnessing the trauma of other people subjected to violence may be triggering ancient fear in all of us, causing us to remain silent.

Because we have a memory of violence in our bones. The more I learn about trauma the more I realize that it affects us in much more subtle and insidious ways than we understand. Some of us have experienced trauma and are easily triggered, but even if we never experienced trauma in our own lifetimes, it can be passed down to us through our DNA. Your ancestors’ trauma may still be causing fear in your own life. Witnessing the trauma of other people subjected to violence may be triggering ancient fear in all of us, causing us to remain silent.- Because our brains don’t understand fear. The most ancient part of our brains – the “reptilian brain”, which hasn’t evolved since we were living in caves and discovering fire – is adapted for fight or flight. That part of our brain sees all threats as predators, and so it triggers our instinct to survive. Our lives are much different from our ancestors, and yet there’s a part of our brains that still seeks to protect us from woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed tigers. When our fear of being rejected by a family member for speaking out feels the same as the fear of a sabre-toothed tiger, our reaction is often much stronger than it needs to be.

- Because those who want to keep us silent have learned more subtle ways to do so. In most of the countries where we live, it is no longer acceptable to flog bloggers, but that doesn’t mean we’re not being silenced. Women have been silenced, for example, by being taught that their ideas are silly and irrelevant. Marginalized people have been silenced by being given less access to education. Those with unconventional ideas have been “gaslighted” – gradually convinced that they are crazy for what they believe.

- Because we have created an “every man for himself” culture where those who speak out are often not supported for their courage. We’re all trying to thrive in this competitive environment, and so we feel threatened by other people’s success or courage. When I asked on Facebook what keeps people silent, one of the responses (from a blogger) was about the kinds of haters that show up even in what should be supportive environments. In motherhood forums, for example, people get so caught in internal battles (like whether it is better to be a working-away-from-home parent or a stay-at-home parent) that they forget that they would be much stronger in advocating for positive change in the world if they found a way to work together and support each other. It is much more difficult to speak out when we know we’ll be standing alone.

- Because we don’t understand power and privilege. Those who have access to both power and privilege are often surprised when others remain silent. “Why wouldn’t they just speak up?” they say, as though that were the simplest thing in the world to do. It may be a simple thing, if you have never been oppressed or silenced, but if you’ve been taught that your voice has no value because you are “a woman, an Indian, a person of colour, a lesbian, a Muslim, etc.”, then the courage it takes to speak is exponentially greater. Years and years of conditioning that convinces a person of their inherent lack of value cannot be easily undone.

Several years ago, I visited a village in the poorest part of India. Though I’d traveled in several poor regions in Bangladesh, India, and a few African countries before that, this was the most depressing place I’d ever visited. This was a makeshift village populated by the Musahar people who lived at the edges of fields where they sometimes were hired by the landowners as day labourers but otherwise had to scrounge for their food (sometimes stealing grain from rats – which was why they’d come to be known as “rat eaters”).

Several years ago, I visited a village in the poorest part of India. Though I’d traveled in several poor regions in Bangladesh, India, and a few African countries before that, this was the most depressing place I’d ever visited. This was a makeshift village populated by the Musahar people who lived at the edges of fields where they sometimes were hired by the landowners as day labourers but otherwise had to scrounge for their food (sometimes stealing grain from rats – which was why they’d come to be known as “rat eaters”).

There was a look of deadness in the eyes of the people there – a hopelessness and sense of fatalism. Our local hosts told us that these were the most marginalized people in the whole country. They were the lowest tribe of the lowest caste and so everyone in the village had been raised to believe that they had no more value than the rats that ran through their village.

There was a school not far from the village, but we could find only one boy who attended that school. Though everyone had access to the school, none of the parents were convinced their children were worthy of it.

It was a powerful lesson in what oppression and marginalization can do to people. In other equally poor villages (in Ethiopia, for example) I’d still noticed a sense of pride in the people. The Musahar people showed no sense of pride or self-worth. Essentially, they had been “gaslighted” to believe they were worthless and could ask for no more than what they had.

The next day, my traveling companions and I took a rest day instead of visiting another village. We had enough footage for the documentary we were working on and we needed a break from what was an emotionally exhausting trip.

My colleague, however, opted to visit the second village. He came back to the hotel with a fascinating story. In the second village, a local NGO had been working with the people to educate them about their rights as citizens of India. It hadn’t taken long and these people had a very different outlook on their lives and their values. They were beginning to rally, challenging their local government representatives to give them access to the welfare programs that should have been everyone’s rights (but that people in the first village had never been told about by the corrupt politicians who took what should have been given to the villagers). On the way back to the hotel, in fact, he’d been stopped by a demonstration where the body of a man who’d died of starvation had been laid out on the street to block traffic and call attention to the plight of the Musahar people.

The people in the second village were slowly beginning to understand that they were human and had a right to dignity and survival.

In the coaching and personal growth world that I now find myself in, there is much said about “finding our voices”, “stepping into our power”, and “claiming our sovereignty”. Those are all important ideas, and I speak of them in my work, but I believe that there is work that we need to do before any of those things are possible. Like the Musahar people, those who have been silenced need to be taught of their own value and their own capacity for change before they can be expected to impact positive change.

First we need to take a close look at the root causes of the fear that keeps us silent before we’ll be able to change the future.

When we begin to understand power and privilege, when we find practices that help us heal our ancient trauma, when we retrain our brains so that they don’t revert to their most primal conditioning, and when we find supportive communities that will encourage us in our attempts at courage, then we are ready to step into our power and speak with our strongest voices.

Like the Musahar, we need to work on understanding our own value and then we need to work together to have our voices heard.

These are some of the thoughts on my mind as I consider offering another coaching circle based on Pathfinder and/or Lead with Your Wild Heart. If you are interested in joining such a circle, please contact me.

Also, if you are longing to understand your own fear so that you can step forward with courage, consider joining me and Desiree Adaway at Engage!

by Heather Plett | Sep 16, 2014 | Community, Leadership

“Keep away from people who try to belittle your ambitions. Small people always do that, but the really great make you feel that you, too, can become great.” ~ Mark Twain

Tomorrow, after I teach a storytelling workshop for a national non-profit, I’ll be heading out on a special annual pilgrimage. A twelve hour road trip in good company will take me to the Black Hills of South Dakota, where I will gather once again with the women of Gather the Women.

This will be my third year in this circle of women. I can hardly wait to be with them again. When I am in this circle, I feel fed, held, honoured, encouraged, and strengthened. Even though we only see each other once a year, women in this circle have supported me through the grief of losing my mother, encouraged me in the growth of my business, and cheered for me every time I’ve done something brave.

But the primary reason why I keep going back?

They call me into my greatness.

These women want me to succeed. They want me to be bold, strong, and successful. They want me to make a mark in the world. They believe wholeheartedly in my work and cheer with their whole hearts when I do it well.

Why? Because MY work is OUR collective work. And because when I succeed, we ALL succeed.

That’s the way it is when you surround yourself with powerful women who aren’t threatened by other people’s power. We succeed together and we leave the world a better place.

That’s the way it is when you surround yourself with powerful women who aren’t threatened by other people’s power. We succeed together and we leave the world a better place.

Are you longing to surround yourself with that kind of support?

I can help. What those women do for me, I want to do for you.

I want to call you into your greatness.

I want to cheer from the sidelines as you succeed. I want to nudge you into those places that feel scary but you know are right. I want to help you find your path.

How can I help you?

1. Come join Pathfinder Circle where you’ll find yourself surrounded by other women who are also daring to find their paths and step into their greatness. (It’s an online coaching circle that meets once a week for 8 weeks, starting September 30th.)

2. If you want to step into your greatness in your writing, sign up for Openhearted Writing Circle. (It’s a one-day online writing retreat, on October 4th, that will help you crack open your heart and pour it onto the page.)

3. If it’s one-on-one support you need, sign up for coaching. If you’re a leader/facilitator/teacher/coach, check out this offering.

Many years ago, when I was in my first leadership position, I realized that helping other people shine is just as good as shining yourself. Because we all benefit from each other’s glow.

Let me help you shine.

by Heather Plett | Sep 7, 2014 | art of hosting, Leadership

This post is part of the 30-Day Bloom Your Online Relationships Challenge. If you’d like to play along, you can sign up here (don’t worry — it’s FREE). We’re working through these small, powerful actions together and sharing our questions, learnings and experiences in a Facebook group. And we’d love to have you join us!

This post is part of the 30-Day Bloom Your Online Relationships Challenge. If you’d like to play along, you can sign up here (don’t worry — it’s FREE). We’re working through these small, powerful actions together and sharing our questions, learnings and experiences in a Facebook group. And we’d love to have you join us!

In the group facilitation work I do (in The Art of Hosting and Harvesting Meaningful Conversations), there’s a mantra that we repeat to ourselves long before we enter the room to host a retreat, facilitate a planning session, mediate a conflict, teach a class, etc. It’s simple – just three words…

Host yourself first.

What does it mean to “host yourself first”? It means, simply, that anything I am prepared to encounter once I walk into that room, I need to be prepared to encounter and host in myself first. In order to prepare myself for conflict, frustration, ego, fear, anger, weariness, envy, injustice, etc., I need to sit with myself, look into my own heart, bear witness to what I see there, and address it in whatever way I need to before I can do it for others. I can’t hide any of that stuff in the shadows, because what is hidden there tends to come out in ways I don’t want it to when I am under stress inside the room.

AND just as I am prepared to offer compassion, understanding, forgiveness, and resolution to anything that shows up in the room, I need to offer it to myself first. Only when I am present for myself and compassionate with myself will I be prepared to host with strength and courage.

To serve the world well, I need to serve myself first.

How do I do that? I do it by being honest with myself about my emotions, by engaging in the creative/spiritual practices that sustain and enrich me, by working things through in my journal or in a walk in the woods, by engaging in self-care, by getting support from the right people, and by claiming my own power and authority before I step into the room.

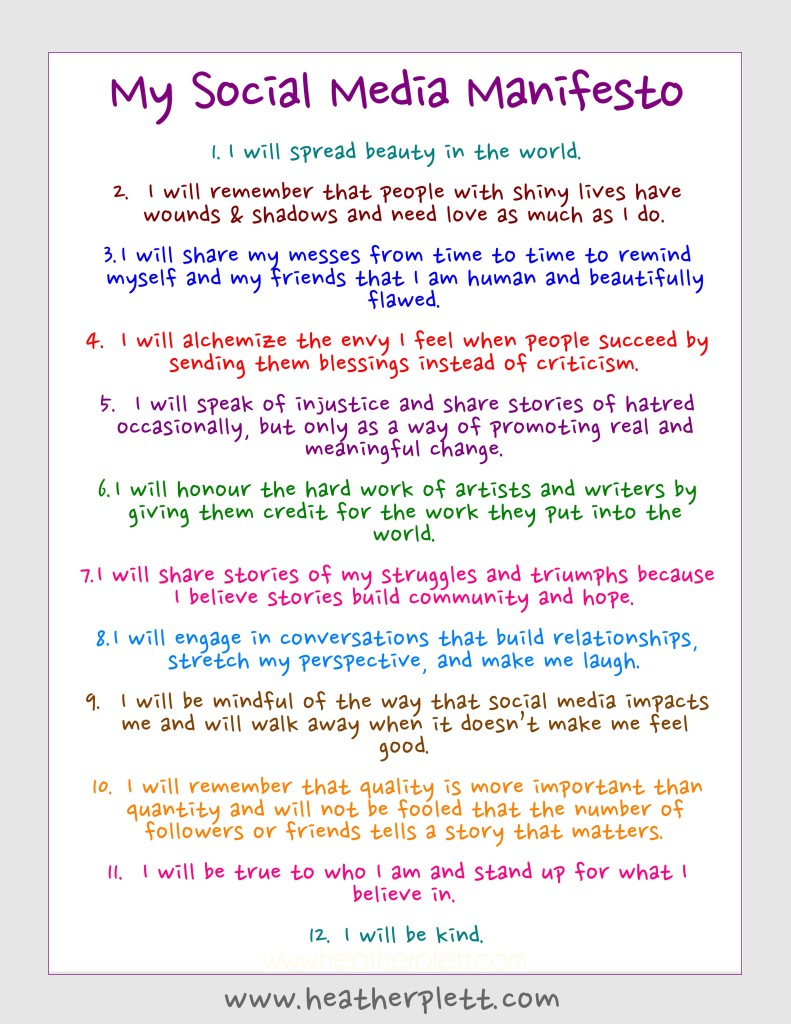

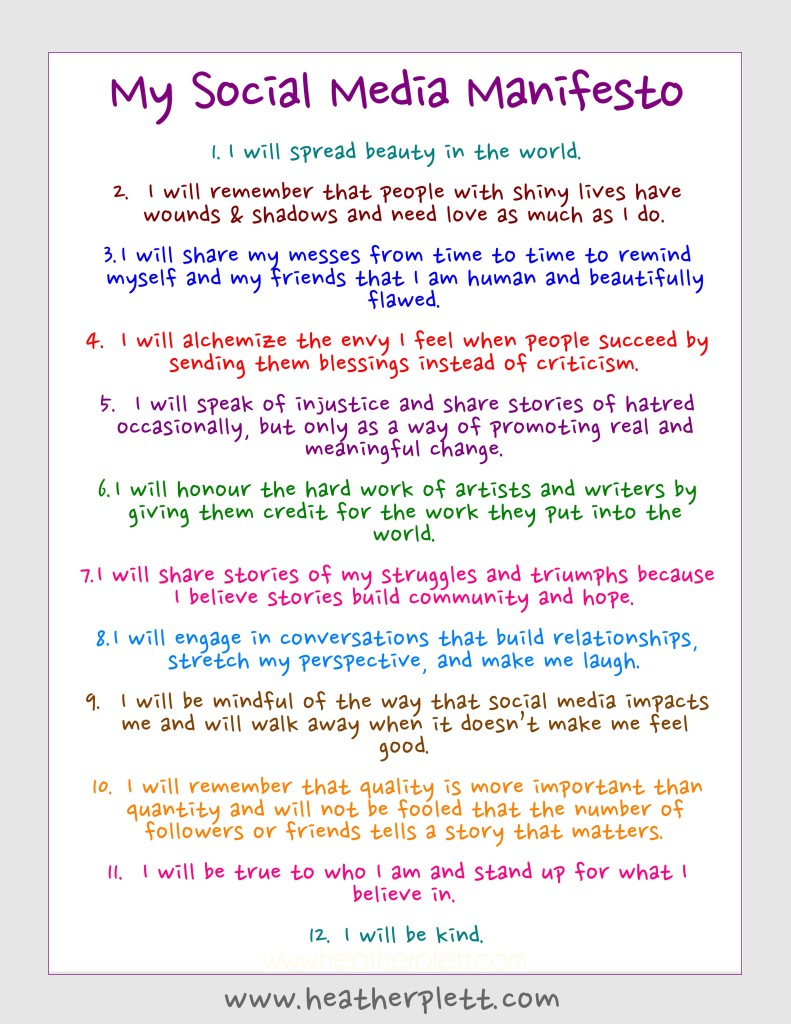

A few years ago, I was frustrated over what was happening on social media and I started questioning my presence there. I was getting dragged down by pettiness, I was feeling pressured into “doing social media marketing the way the pros tell me to”, I was wasting too much time in mindless surfing, and it was all feeling rather icky. I was suddenly painfully aware that I’d let go of my authentic voice and my sense of purpose.

And then the words I’d repeated so often in my in-person work came back to me… “Host yourself first.” Oh yeah… right.

So I asked myself, “what if I apply this to my presence on social media?” What if, when I’m on Facebook or Twitter, I take myself more seriously and consider myself to be “hosting meaningful conversations” the way I’m doing in retreats and in the classroom? What if – before I post anything – I check in with myself to test the emotions around what I’m posting and to make sure it’s coming from a place of authenticity and positivity rather than ego and marketing? What if, before I walk into the “room” on Facebook, I make sure I’m clear about my own values and passions and boundaries? How will that change the way I interact?

I started experimenting with it, and it didn’t take long to realize that my online presence had shifted. I was returning to my authentic voice. I wasn’t just posting for the sake of being popular or funny or to make a sale. I didn’t do anything just because the pros told me I should do it, but instead I did what flowed organically from who I was and how I wanted to be in the world.

To solidify my commitment to hosting myself first online, I wrote my social media manifesto, naming all of my intentions in how I wanted to show up online. (Click on it to see it larger, or scroll to the bottom of the page.) I shared it and invited others to do the same.

To solidify my commitment to hosting myself first online, I wrote my social media manifesto, naming all of my intentions in how I wanted to show up online. (Click on it to see it larger, or scroll to the bottom of the page.) I shared it and invited others to do the same.

People started responding. Beautiful conversations resulted. New and deeper relationships grew. More people bought what I was selling because it was coming from the kind of authentic heart that people were longing for. My business grew and my social media reach grew, but more importantly my relationships grew.

How do you host yourself first?

Here are a few tips:

1. Do your personal work before you go online. Start with whatever creative/spiritual practice sustains and enriches you – art, meditation, journaling, dance, walking, etc.

2. Sit with your emotions before you broadcast them. Are you angry, sad, disappointed, confused? Sit with them for awhile, without judgement, and honour what is showing up. Ask yourself: “Is this is an emotion that is worth sharing (and perhaps asking for support for) or worth holding close to my heart?”

3. Ask yourself each day how you can be of service to the world. How can you serve the people in your social media stream – with uplifting posts, with humour, with invitations to justice and compassion, with offers to support them, with meaningful conversation, with reminders of how beautiful/kind/courageous/resilient they are?

4. Remind yourself that each person in your social media stream (including yourself) wants to be loved. When you think of it that way, then the things they do that annoy you are softened somewhat because you recognize in them a quest for attention and love.

5. Choose your own mantra that you repeat to yourself before you post or respond to anything. It can simply be a question: “Is this authentic to who I am?” or “Is this serving the world in a positive way?” Or a statement “I choose beauty.” or “I am a messenger of light.”

6. Think of yourself as a facilitator or host when you appear on social media. If this were a party or retreat you were hosting, what kind of atmosphere would you like to create? How would you like to make people feel about themselves? What kind of conversations do you want to facilitate?

7. Be as kind to yourself as you would be to anyone else you’re hosting. If you were hosting a party and someone was feeling down and discouraged, you’d sit next to them and listen to them and offer encouragement. If they were celebrating something, you’d celebrate with them. Offer the same kind of compassion, encouragement, and friendship to yourself. When you do that to yourself first, you’ll feel much stronger and more able to withstand the highs and lows of social media engagement.

8. Write your own social media manifesto. Start by journaling about all of the things that are important to you about how you want to engage online. Then write a list of your commitments. Share them or keep them to yourself – whatever feels right. If you want to, share them in the BYOR Facebook group.

NOTE: When you’re done trying out today’s challenge, come visit us on Facebook and let us know how it went. What did you share? What was the response? Was it easy for you? Hard? No right or wrong answers here — we’re all just experimenting!

Image credit: Leyton Parker

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

The game begins once again, but what people don’t realize until they’ve played a round or two is that the rules are different at each able. At some tables, ace is high and at other tables it’s low. At one table, diamonds are trump, at another clubs are trump, and so on.

Several years ago, I visited a village in the poorest part of India. Though I’d traveled in several poor regions in Bangladesh, India, and a few African countries before that, this was the most depressing place I’d ever visited. This was a makeshift village populated by the

Several years ago, I visited a village in the poorest part of India. Though I’d traveled in several poor regions in Bangladesh, India, and a few African countries before that, this was the most depressing place I’d ever visited. This was a makeshift village populated by the